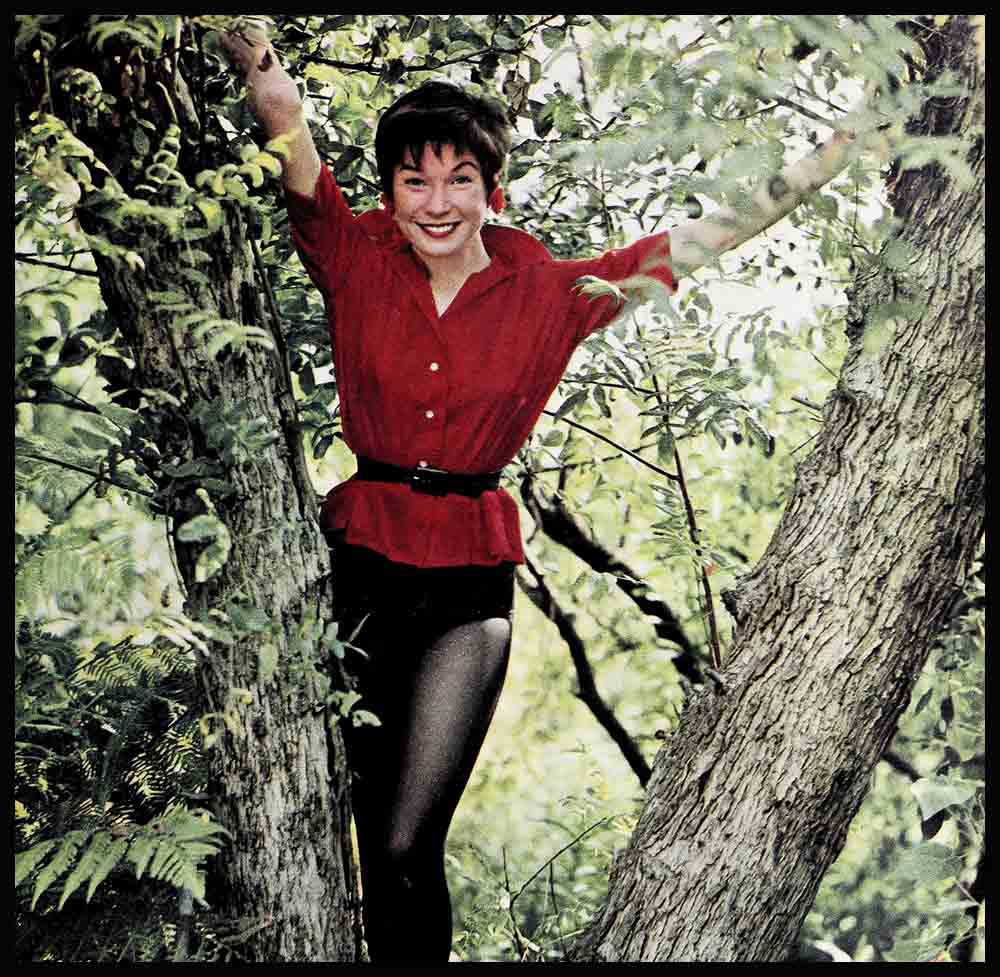

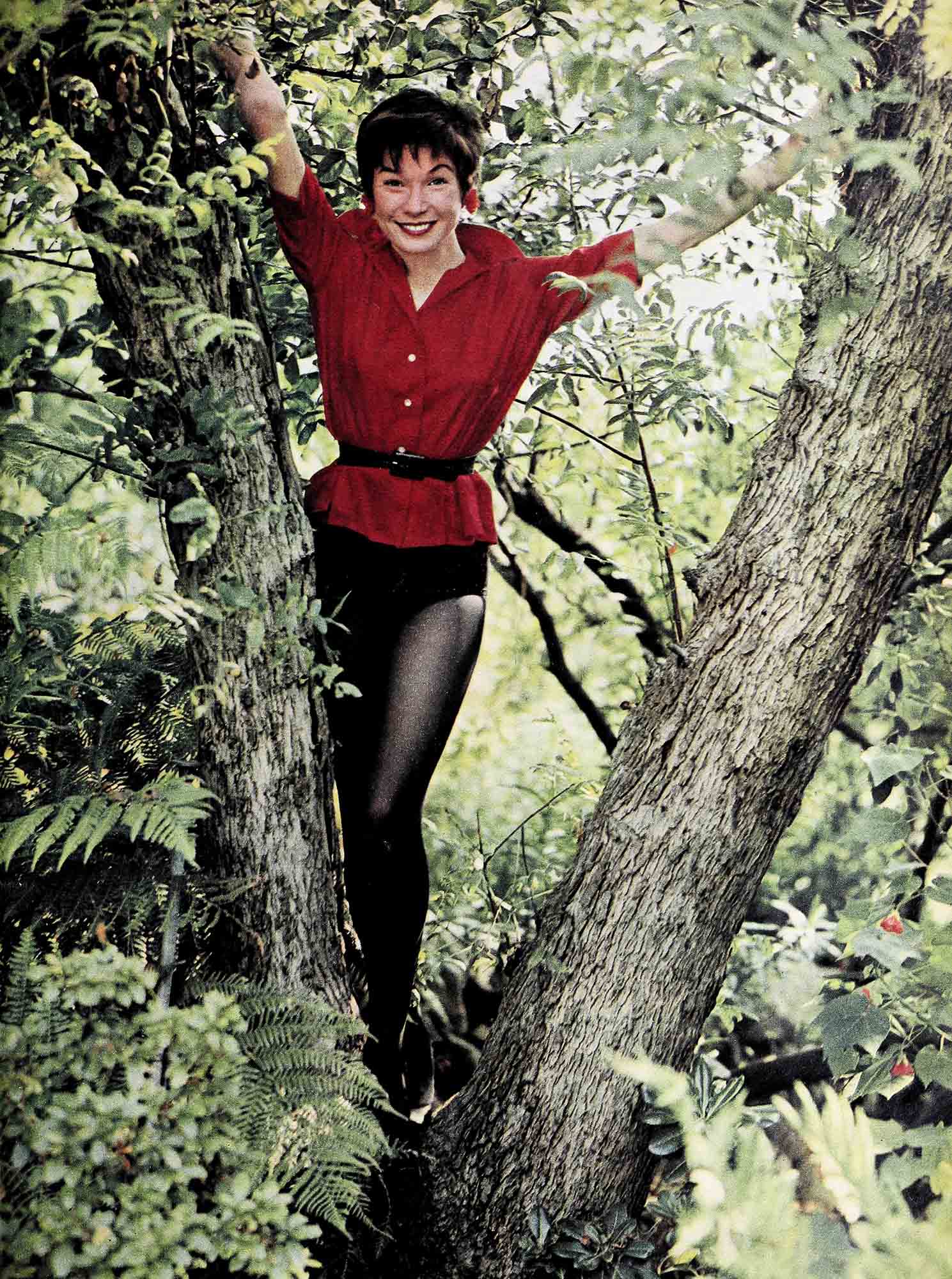

Love Has Shirley Up A Tree

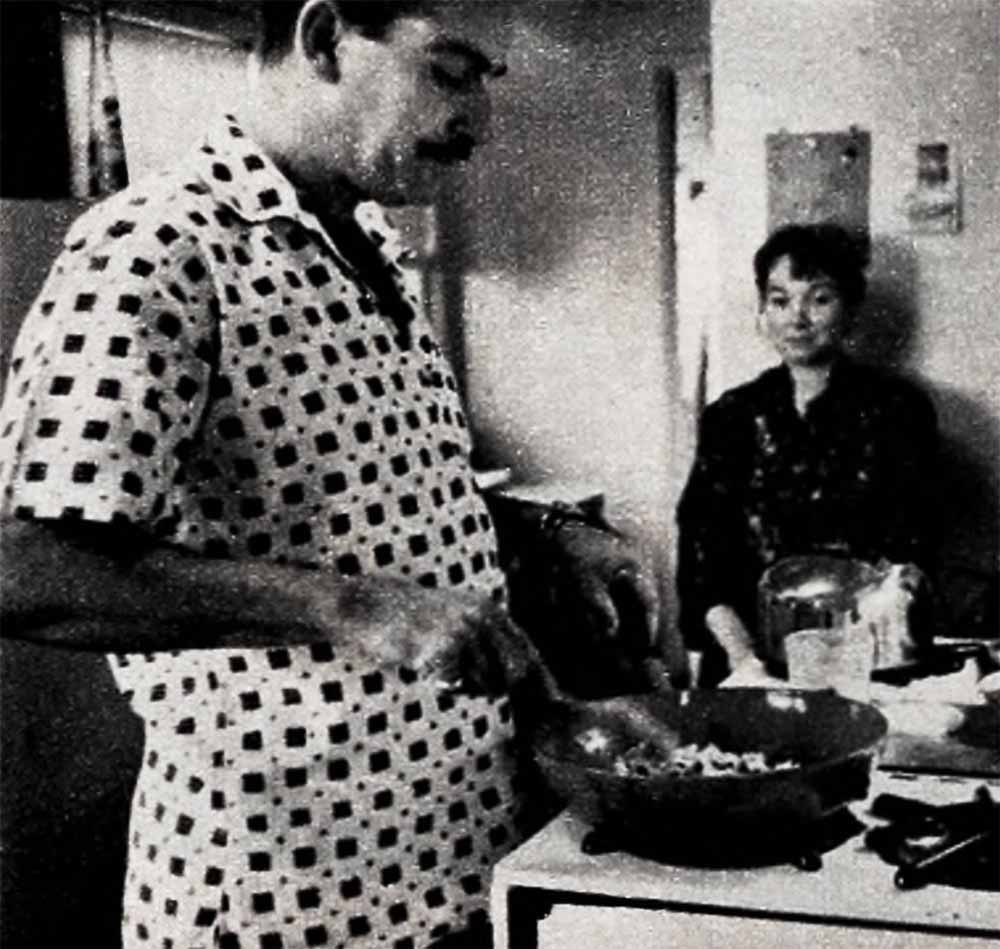

Another last breakfast. Steve’s famous scrambled eggs. Just like the last time, before he went away, Shirley MacLaine thought as she watched her husband put the final touches of fresh mint to his favorite breakfast concoction. She wanted to shout out—all the thoughts and feelings that seemed to be swirling around her head. Instead, she simply sat quietly, silently watching Steve turn the eggs in the pan, as if she were seeing it for the first time.

She looked up at the big kitchen clock, and wished she could stop its ticking.

In less than an hour Steve would pick up his packed bags, kissed her and the baby goodbye gently and leave for the International Airport and Japan. This time, she wasn’t going to take him to the airport, she had told Steve. İt hurt too much to see him board the plane. And, somehow, it was even lonelier to return home to try to pick up a life without him. The last time, when she got home, she vowed the only time she’d go back to the airport was to pick Steve up on his homecoming.

In four years of marriage, they had been together just a little over a year. But you never get over separation, she thought as she handed him a potholder and tried to return his wink with a smile—when you’re in love . . .

“Sorry, honey,” she remembered his saying as he left for Japan that first time. “We’ll find a way. It won’t be too long.”

And she remembered answering something flip and gay, something zany, as she always did when she felt lost for the right word. “The Japanese motion-picture industry can’t do without your talents,” she’d said. There was a chance in Japan for Steve to produce and direct the kind of things he wanted.

As for her—“Your career is hot,” he told her for the hundredth time. “You stay here. You’ve worked all your life for this. You can’t give it up for a few months with me in Japan.”

She agreed. Steve was always right. Without him, without his advice, his coaxing, his planning, she’d never even be in Hollywood or at Paramount. When they met in New York she was struggling as a chorus dancer in Broadway’s “Me and Juliet.” Nothing much was happening, ’til Steve Parker.

“Yes, Mr. Director,” she would kid him as he would line up a dozen things a day for her to follow—leads, lessons, even books. She found she needed him all the time—and for some crazy reason, he’d said he needed her. They were married.

When he left—not long after that—she thought she’d never learn not to depend upon him so much. For little things like listening together to the surf outside their cottage, walking along the beach early in the morning and watching for the sun to come up. When there was no one to share these with, she found herself starting out for the studio a little earlier each day—taking a different route, adding a few extra miles to the forty-five-minute ride from Malibu to the studio, and staying as late as she could in the evening, as long as there were other people around. She didn’t realize it at first, but she hated going home. The complete aloneness had been so frightening.

“What’re you thinking about?’’ Suddenly she heard Steve talking to her. “Come on,” he teased. But she couldn’t tell him . . .

Last night, Steve’s last at home, while he was doing some final packing before eating dinner, she had picked up the evening paper and there, in a carefully buried gossip column item, her own name had jumped out at her: “Is Shirley MacLaine hiding a marriage rift?” she read. She hid the paper so Steve wouldn’t see it, knowing it would upset him. And luckily, later they were too busy talking and Steve never asked for the evening paper.

Dinner had been fun. Even Stephanie stayed up late and they ate on the patio, all three of them, discussing the future and their plans. Steve had told her how much he liked the Japanese flower arrangement she had made. Inwardly, she was pleased. But all she’d answered was, “And not the angel food cake?”

Angel food cake . . . This was one of hers and Steve’s pet jokes. once she had written to him: “All I want to eat is angel food cake!” What she didn’t know then was that she was going to be a mother.

“It was all so sudden,” she remembered telling a good friend, a writer. “I’d been devouring angel food cake at a ferocious rate for two months. It suddenly dawned that my diet was definitely unusual. I hied to a doctor and found out I was pregnant. I was kind of mixed up. Steve and I wanted a family, but after we were both established in our careers. I loved the idea of a baby, yet, you know, I kind of resented being alone with seven months of problems to solve.”

Steve’s letters had kept her going. She could tell he was doing beautifully. And she clung to his successes as she would to a child—feeling them a part of her and reminding herself that her loneliness was for a purpose. And her letters to him . . .

“A new world is opening up to me,” she had written him. “A world involving instant individual decisions, a world of other people, other problems. There is no Steve to help decide, no Steve to pour out the day’s happenings to, no strength for my weaknesses. I suffer from—a feeling of homesickness even more frightening when you’re away and I’m at home.

“But I really look into people’s faces now, noticing things I’ve never noticed before. I see emotions in others. For my short lifetime, I’ve been wrapped in the protective cocoon of my one-tracked work toward a career. With you, it was simply a matter of enlarging that cocoon to include two. Now suddenly I understand human emotions, lives and loves of others. Realizing, too, it has taken me much too long to break open my cocoon and try my wings. As I drive to Malibu at night, I can honestly say that pain and unhappiness bring more understanding and growth than practically anything . . .”

And then, at last, he was home again—two days before Stephanie was born—September 1, 1956. Almost nine months of catching up, making of plans and re-avowals of strength had to be done in three weeks. She had been positive about moving into town when he’d come home—away from the isolation and loneliness. But he was persuasive. By the time he’d left, he had convinced her all over again that she loved the ocean, wanted to be away from people and really needed it.

“More coffee, sweetie?” The sound of his voice pulled her back to the present once again. She’d hardly touched the food in front of her.

“I wonder how Bob Mitchum will be to work with,” he was saying now. “Honey, I tell you, this is the most exciting thing that’s happened to me. Do you really like Masterspy’ as the title? Gosh, I wish you could come with me . . .” his voice trailed off.

As she matched his face, she felt the old loneliness returning, yet at the same time a deep understanding of his needs. “I wouldn’t want us to be together all the time, even if we could. Steve needs freedom. He shouldn’t ever conduct his whole life for me,” she had recently explained to a friend who asked about her marriage, and she realized she was becoming more independent. Up until then, she had relied to an extent on Steve’s decisions for her by letter. But slowly she had been pushed into making daily decisions, some of them very important to her career and herself. She’d started getting the feel of saying yes or no—for herself. She remembered the first big one. She’d nearly stuttered when forced to decide, but she’d done it . . .

Right after Steve left the second time she was offered a role in the stage production of “The Sleeping Prince.” Steve wrote that he thought she shouldn’t do the show at all. But she figured it out carefully for herself. She needed to work and so she decided to take the part. It was the month after Stephie was born and she was nursing her. Poor Stephanie. She went to all the rehearsals, but she really had a ball. And Shirley, after opening night, had a hit on her hands.

By the next time Steve came home, he had won top awards at the Southeast Asia Film Festival for his documentaries, yet his enthusiastic chatter about his work and the awards hurt her a little, and he noticed this change in her. She began flaunting her ability to make decisions under his nose and waving her new independence. Luckily, Steve had understood. Perhaps it was good he could not be home longer than two weeks that time. For by the time he’d returned home for another two weeks, she had gotten over her anger and had become an individual. And for the first real time in their marriage they were together as two people wanting to merge, not just one leaning heavily on the other. It was wonderful . . . except they still seemed no nearer to a decision of how to stay together.

“You’re still a practical idealist,” she suddenly said to him across the table.

“Is that what you were thinking, honey?” he laughed.

It was true. His ideas for a world film company, working for international understanding, meant he would be constantly somewhere other than home. Where does that leave me—and Stephie? she had so of ten asked. There was no answer.

After Steve had left on one trip, she’d sat looking out the lanai window, listening to the surf. all of a sudden she made the decision. Stuffing Stephie into the MG, she headed for Hollywood, found a realtor and told him she wanted a house to rent—close to town. And they’d found one, high on a hill, just off the Freeway. And she took it. She would make a really wonderful new home for Steve to return to.

Then, how she’d thrown herself into the project of the new house! Painting, varnishing, waxing, rearranging.

She looked through the kitchen door, at the black chairs in the living room corner.

She hadn’t been able to sleep one night, so had gotten up at four a.m. and gone to

work on them. They still looked pretty good, she thought. She’d hung up Japanese parchment lanterns, a final touch to the Japanese modern decor. I want Steve to feel at home, she had kept telling herself.

“Are you going anywhere tonight, honey? Why don’t you?” The sound of Steve’s voice once again prodded her out of the past. He knew how hard the first few nights alone always were for her. . .

She’d been invited out to the Valley tonight for dinner with some friends, a married couple. She wasn’t too keen on going—last time they had sat and bickered much of the evening about whether to play the hi-fi, talk or watch TV. She had wanted to scream at them, “It doesn’t matter what you do. You’re together.” But she hadn’t. She didn’t have many friends. She wanted to keep them.

“I don’t know,” she answered quietly, stirring her coffee. ”Maybe I will. It’s nice living near enough to town to see people in the evenings if I want to. I’m not afraid of the talk any more.”

“You know I love you, darling, and want you to enjoy yourself. Remember what I once told you about being a bamboo and bending with the circumstances?”

“I could give Stephie a late nap and take her with me . . . All right, I’ll go.” Steve smiled gently. “ I’ll go kiss her goodbye now. And then I’ll get my baggage together. Thanks for my last American breakfast. honey. Delicious. Back to raw fish and green tea.”

He bent over to kiss her. and held her for a long moment. And. as he walked out of the kitchen, she felt the familiar tears and the hurt well up inside. There was so much she wanted to say, so little time to say it in. She felt like a child, helpless, wanting to hold him back.

“Shirl . . . Shirley.” She heard him call her from the driveway. But she sat, frozen. She couldn’t go out there. She walked to the kitchen window and watched him as he turned to throw her a last, lingering kiss, then drive away. The morning sunlight streamed in from the patio but this morning it didn’t warm her. Upstairs, she heard Stephanie. But she couldn’t go to her, not yet.

“Be a bamboo; bend with the circumstances.” Steve’s words haunted her.

Only time would tell how they would work out their separations. And the only answer in the now quiet house was a sudden gust of wind touching at her hair.

THE END

SHIRLEY’S IN PARAMOUNT’S “THE MATCHMAKER” AND M-G-M’S “SOME CAME RUNNING.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1958