Having A Memorable Time—Doris Day

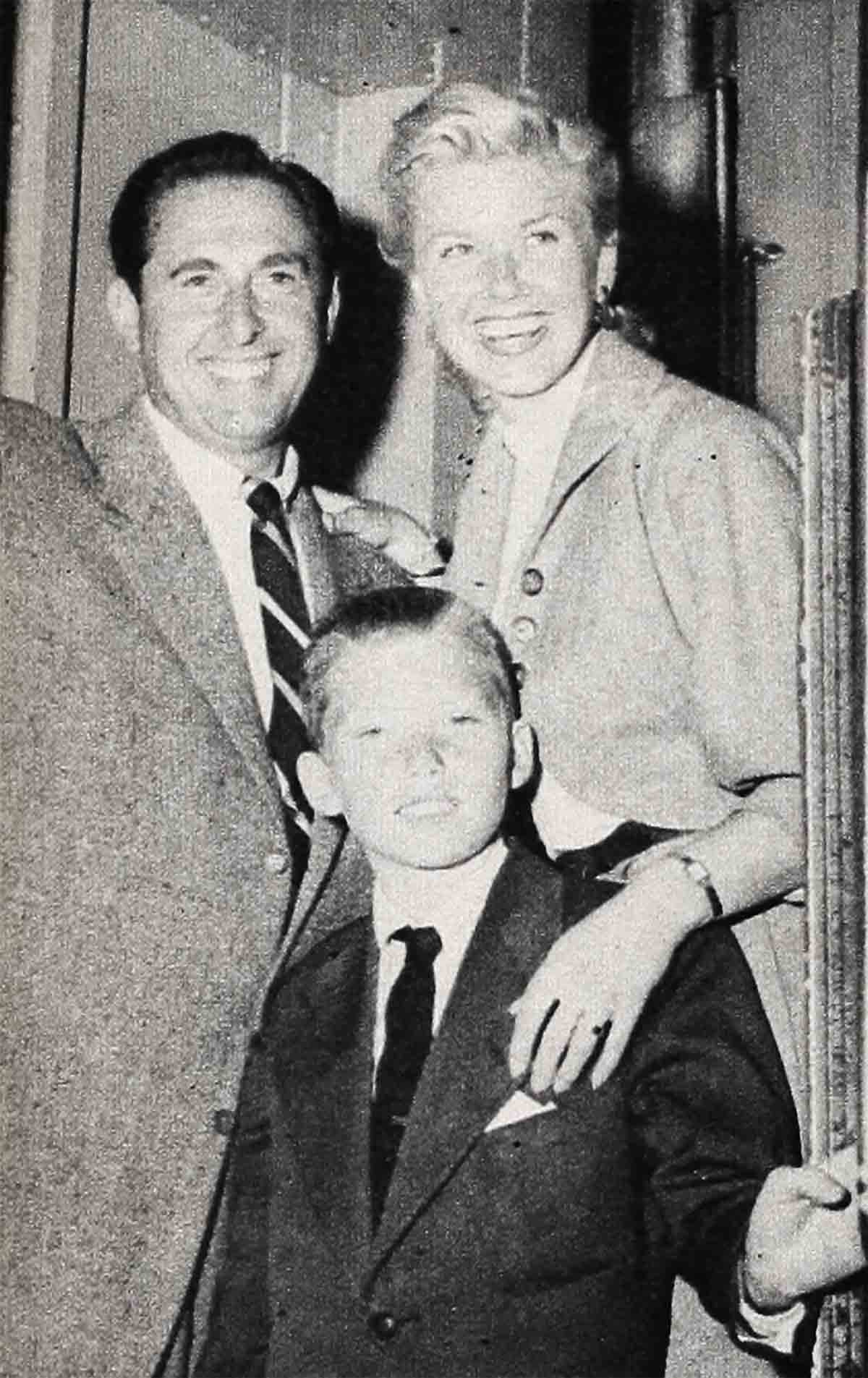

According to the calendar it was still winter, but spring was already in the air the afternoon Marty Melcher and his Mrs., professionally known as Doris Day, were heading back from M-G-M across Cahuenga Pass, to their San Fernando Valley home.

It had been Doris’ last day at the Culver City studio, where she had just finished “Love Me or Leave Me.” There was much she had to tell Marty. With the last minute rush of dubbing, publicity and catch-up shots, for the past few days she’d had to leave her house earlier than usual, get back later than customary, was too exhausted for much conversation while home.

Suddenly, seemingly without cause, Doris stopped talking. A far-away look crept into her eyes as her mind wandered to distant places, carried along a path of strings and saxophones, to the melody of “With the Wind and the Rain in Your Hair.”

“What were you saying about that last scene?” Marty inquired.

“There was no reply.

“Doris . . .”

“Hmmmm . . .”

“You were telling me about that last scene today . . .”

“I was? Oh, I’m sorry, Marty,” she burst out. “I was listening to that song. It suddenly reminded me of Cincinnati.”

Just why it did, Marty didn’t find out. Already Doris’ thoughts had skipped back to the time she was trying to get a job with Bob Crosby and his band. To avoid the long and expensive trip to Chicago for try-outs, she had followed her voice teacher’s advice and recorded “With the Wind and the Rain in Your Hair,” which she sent to Mr. Crosby, who promptly hired her.

A smile formed on Marty’s face as he drove on. He didn’t mind her absentmindedness. By now he knew he’d married Hollywood’s most sentimental girl.

From baby pictures to frayed pillow cases, Doris attaches a special meaning to almost everything. As a teen-ager, she kept her first corsage in the refrigerator not just until it wilted but till the boy who gave it to her was going to military school—two years later! Even then she threw it away only on her mother’s urgings, and with tears rolling down her cheeks.

As she grew up, her collection of memorables grew to the point where, when traveling with Les Brown and his band, she carried with her as many knickknacks as clothes. She held on to her continually growing collection till the lack of available housing and her inability to pay the prevailing rents when she first settled in California forced her into a trailer. As she could save but a few prized pieces from her vast accumulation, whenever something happens to these left-overs, Doris is brokenhearted—as a few weeks ago when she accidentally broke a tulip vase handed down from her grandmother.

Understandably, most of her memories are connected with her childhood. Rarely an opportunity slips when Doris can’t tie in a present activity with one of bygone days. Like the first time this year she and Terry were taking a dip in the pool. “Gee, mom, isn’t this fun?” her young son exclaimed as he splashed around in the water.

“Sure is,” Doris came back, and then the familiar look came into her eyes again.

“OK, Mom,” said Terry, by now quite initiated. “What does it remind you of.”

“Middletown.”

“Middletown? Where’s that?”

“Middletown, Ohio. That’s where I used to go swimming when I was your age. It was wonderful.”

She told him how five or six times a year, her mother used to squeeze her and half a dozen of her school chums into the family sedan and head for the little Ohio town, forty-odd miles away. It was the closest place with an out-door pool and enough ground surrounding it to have fun on a picnic. “You mean you went swimming only five times a year?” Terry gasped. “Gee, that’s nothing.”

“I bet I did as much swimming on each trip as you do in a week.”

She did, too. Doris never settled for a few quick dips. She dove into the pool as soon as she had changed into her bathing suit, emerged just long enough to stuff herself with some lunch and jumped back into the water till she was blue with cold and shivering. Those five or six hours as a mermaid had to sustain her a good month.

Another type of outing which she fond- ly remembers was the yearly excursion to the largest amusement park in Ohio. All year she used to save for the hour-long boat ride upstream. She still recalls the afternoon she came back, leaned on the railing, watching the paddle wheels scoop up the water. She was dreaming how much fun it would be to have enough money someday to spend all her time at a place like this.

Today she could afford a park of her own. But it couldn’t compare with the old Ohio amusement park.

For Doris, thinking, or even talking about the past, isn’t half the fun of reliving some of the events. Marty found that out when he had to take the brunt of it the last time they visited Cincinnati.

Much to his surprise, a couple of hours after they arrived Doris maneuvered him to a dilapidated-looking clothing factory. “What on earth for?” he wanted to know.

“This used to be a dance hall,” Doris explained with an intonation which implied it was second in importance only to the capitol building in Washington, D. C.

“So?”

“So, this is where Barney Rapp gave me my first singing job.”

And for additional sentimental value, this was also where Doris changed her name from Kappelhoff to Day.

It is understandable that someone as sentimental as Doris would always have a close attachment to her dogs. Of the dozen she owned at one time or other, none was closer to her heart than Tiny, a brown and white Manchester terrier.

She particularly recalls the day—one of the few she’d like to forget but can’t—when she went for her first walk after having been indoors for fourteen months, following her accident. She was still on crutches when she left the house that fateful morning. Tiny was with her, running back and forth, circling her and jumping up and down full of exhuberance. His loyalty to his mistress was distracted only when he spotted a fellow canine across the street. Without hesitation, he suddenly shot across—but didn’t quite make it. Doris let out a terrified scream as the car hit Tiny. He was killed instantly.

She thinks of him everytime she sees a terrier that looks like Tiny. As far as she’s concerned, practically all do.

A few days after she finished “Love Me or Leave Me,” she went for a walk, along the quiet, tree-lined streets of her neighborhood. About four or five blocks away she saw another Tiny in someone’s yard. She promptly called him closer to the fence, and when his owner stepped out of the house, Doris and she discussed their dogs like mothers compare notes about their babies.

For that matter, Doris always talks about her two poodles, Smudge and Beany, like they were people. She acquired Smudge several years ago when she went to the Landsdowne Studio in Hollywood to have pictures taken. She almost fell over him when he wouldn’t budge.

“He’s always lying in the way,” the photographer apologized. “Frankly, I don’t know what to do with him. My landlady won’t let me take him home and this is no place for a dog. I may have to give him to the pound.”

“To the pound?” Doris cried out. “You can’t do that.”

“I have no choice.”

“Oh, yes, you have. You can let me have him!”

Before she could change her mind, he agreed, “It’s a deal.”

Doris is so concerned about Smuge and Beany, acquired a little later, that she even fibs about their ages because she doesn’t want them to grow old. When asked, she usually replies, “They’re three and five.” They’ve been three and five almost as long as Jack Benny has been thirty-nine.

As could be expected, Doris is senti- mental about milestones in her career. Many actresses have their scripts prettily bound and stashed away in their library. Doris goes one step further. Quite frequently, she thumbs through them, reliving the parts she has done, associating the stories with her co-workers.

To most people, family pictures have sentimental values. But we doubt if many go to Doris’ extreme of cluttering up every inch of available space not only with pictures of themselves and their families, but even with snapshots of houses occupied by their relatives. One of Doris’ most cherished possessions is the picture of the house in Germany once occupied by her mother’s cousin. And the first time she returned to Cincinnati after having made a name for herself in Hollywood, she invited all her old school chums to her aunt’s house—with a request to bring along their graduation pictures!

Naturally, Doris fondly remembers the dishes her mother made when she was a child. Like sauerkraut and spetzles and dozens of other German foods. Fortunately, her mother still lives close enough to regularly cook her daughter’s favorite meals. It’s a different story with the meal hours to which Doris has been accustomed.

Her father was a church organist, who supplemented his pay by giving music lessons in the afternoon. Because he could get home in-between times and because it was customary in the “old country” the Kappelhoffs’ luncheon was the big meal of the day. As a result, Doris is one of the few Hollywood stars who can consume a truckdriver’s meal every noon. Not just because she’s hungry, but because it brings back memories of her girlhood.

Doris’ recollections of the past cover a wide variety of subjects, interests and objects—including perfume. The salesgirl of a local department store found that out when she inquired why Doris usually ordered “Tweed.”

“It reminds me of Toronto,” was the strange reply.

The salesgirl looked at her disbelievingly. Perfumes are supposed to remind people of romance, of moonlit nights and soft music. But Toronto! Curiosity got the better of her. “Why?”

“Because that’s where I sang with Barney Rapp and his band when we played for the Druggists’ Convention. Everyone, including me, got a tiny souvenir bottle of “Tweed” that night. Ever since “Tweed” reminded me of Canada. I liked it up there.”

It’s quite amazing that a girl like Doris didn’t hold on to what so many people cherish most—letters. They were always destroyed as soon as she finished reading them.

In another way, Doris differs from other sentimentalists, which may account for her usually well-balanced and happy disposition. Whereas some people will collect such paraphernalia as broken skis, plaster casts off broken legs and arms, steel helmets and captured rifles, Doris hangs on only to objects connected with happy events.

When, after she had recovered from her accident, someone suggested she keep her crutches, she ignored the advice and gave them to someone who needed them for other than decorative purposes. Likewise, her casts, liberally covered with signatures, initials and good wishes of friends and relatives, were thrown away as soon as they came off.

According to her philosophy, it’s just as easy and a great deal more gratifying to think back on the happy, constructive events in one’s life than to relive those memories which entailed only unhappiness and tragedy. No wonder she’s so fond of her memories.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1955