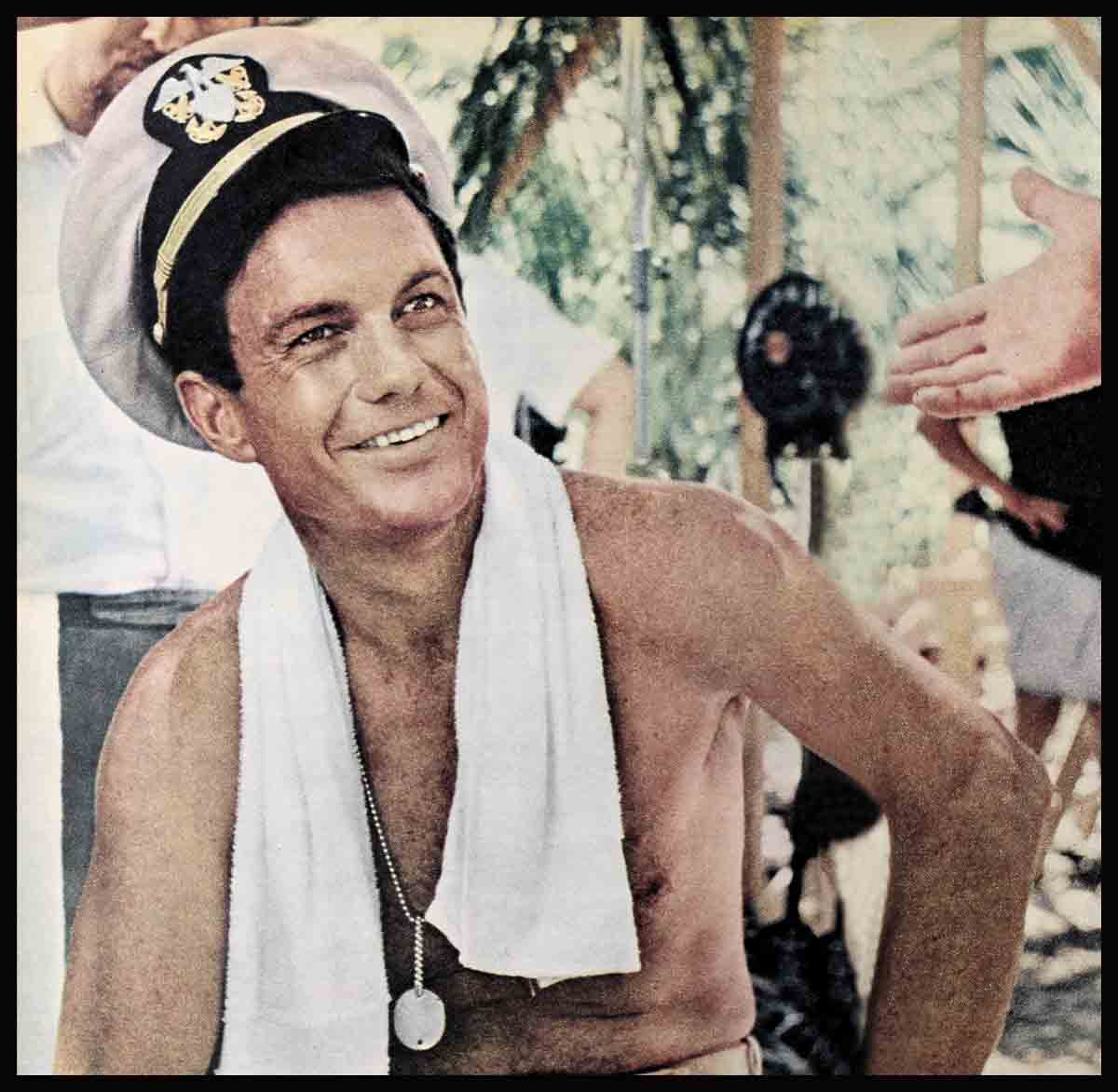

“JFK Is Talking Over My Life!”—Cliff Robertson

There are those who will tell you that somewhere in Washington, D.C., there is a top secret file on Cliff Robertson. His life was combed with the finest of teeth: his marriage to the ex-wife of Jack Lemmon in 1957; his divorce in I960; his political background; his religious views; the organizations to which he belonged since his seventh birthday; the names of his acquaintances and friends. Everything was checked for scandal. And then it was re-checked and double checked.

At last, the word shot westward from Washington to California. The President of the United States would not be unhappy to see Cliff Robertson portray Lieutenant Junior Grade John F. Kennedy in the motion picture “PT 109.”

When Warner Brothers first decided to make “PT 109″ last year, only one favor allegedly was asked. The President would like to approve the actor who would impersonate him on the movie screen.

Every actor under thirty in Hollywood lined up at the gates of Warners’, panting for the role. Figuratively, the line stretched twice around the block and back again. Hundreds of names were discussed.

Amidst all this panic Cliff Robertson played “horsie” with his four-year-old daughter. He was thirty-seven years old; Lieutenant JF Kennedy had been twenty-four. Besides, Cliff wasn’t box office. For ten years his classic, careful, sensitive television performances had won him admiration, awards, and roles in mediocre pictures.

“You must be a great actor,” a producer once said to him in awe. “No one else would be alive in this town after all those lousy pictures.”

A phone call

When the telephone call came, requesting him to do a screen test for “PT 109,” he said grimly, “You must be making a mistake.” Assured that “There is no mistake,” he tested reluctantly and then dismissed the incident From his mind. It puzzled him, but he accepted it as one of the nonsensical things that occur in Hollywood. No stranger that a lot of things.

He tested on Tuesday. The following Saturday, he and his daughter were riding two of her five-horse stable of stick horses around the living room of his apartment. The telephone rang.

A friend was calling from New York. “My God, Cliff, your picture’s in all of the New York papers next to a picture of President Kennedy.”

Since Robertson’s agent wasn’t informed until Sunday, the word must have leaked from Washington on Friday night as soon as the President saw Robertson’s test.

There is probably no answer to the question of “Why?” And Robertson himself has stopped asking. Had the President watched one of Robertson’s television performances some time during the last ten years and been impressed? Or was it more? Did he want someone stronger than a boy to walk across the screen in his uniform, and did he find in Robertson some quality of character similar to his own?

“It would be presumptuous of me,” says Robertson, his fingers fingering fingers, his soft brown hair somehow too young for his face, “to compare myself to the President of the United States. I even had difficulty adjusting myself to the role in ‘PT 109’ because I felt it presumptuous of me to impersonate the President of the United States.

“I wish I had his brains and his good looks. He’s got a fine, fine mind. The more I studied him, the more I realized that. I study and dissect every character I play p trying to find the key that unlocks. That way, each character takes over my life. And now, JFK has taken over my life. But, with President Kennedy, the outside was easy. I could imitate the way he walked and combed his hair. I could have imitated his accent too, but he didn’t want his accent imitated.

“But what was he really like then and why? I had the help of the survivors of the real PT 109 in finding out. I talked to them for hours trying to piece together a picture of young JFK. He was a very popular skipper and history didn’t do that. He did it—by consideration, by trying to con fresh bread or fresh vegetables for his crew from any ship that had arrived with some.

“There are two keys to Lieutenant Kennedy, I think.

“The first is his family. It constantly encouraged competition, forced him to do his best. That’s obvious in the effort all the Kennedys put into their sports, their conversation, their politicking. And yet in the President—in spite of that fierce competition—there is a splendid sense of humor, a quick and witty tongue, a way of not taking himself too seriously that made tough situations easier.

“The second key is his absolute, obdurate, unyielding stubbornness for something he believes in. His very stubbornness was responsible for their surviving the ordeal. His absolute inability to give up saved them. He’s one of those rare people who are just unable to give up or give in.”

Robertson’s silk suit rustles as he moves. It is pale grey, and its pallid softness gives him the appearance of gentleness, of hesitancy as he laughs. “I said I wouldn’t compare myself to the President, but I’ll compete with him in one area. Caroline is wonderful, but my four-year-old daughter, Stephanie, is every bit as wonderful. I’d rather talk about my daughter than about the President. And if President Kennedy had his druthers, I think he’d rather talk about Caroline than Khrushchev.”

Wealth vs. poverty

Much of Robertson’s gentle manner, his hesitancy, is a trick. Beneath what he calls his “laziness,” his ability to drift unruffled with the current, is what you might call a steel different from—and yet in many ways similar to—the steel inside Jack Kennedy.

While John Fitzgerald Kennedy emerged from a cocoon of wealth to become a man. Cliff Robertson had to climb out of the worst sort of poverty—the loss of both his parents before he was three years old.

They were young when they married—too young. The nineteen-year-old boy who became Robertson’s father had been too spoiled and indulged as a boy ever to become a man. In the end he deserted his two-year-old son. Six months later Robertson’s nineteen-year-old mother died of a ruptured appendix.

He was raised by his mother’s mother—a proud and stubborn woman who would never accept what she called “charity” from her wealthy ex-husband. To support three grandchildren and a daughter in the hospital with tuberculosis, she became a nurse. While Joseph P. Kennedy was setting up a $1,000,000 trust fund for JFK. Cliff was putting the dimes he made from selling magazine subscriptions into an empty fruit jar. Two years later he had saved enough to buy a second-hand bicycle.

But if the old house in La Jolla was shabby in most ways, it was rich in family history. Robertson’s ancestors had come to America half a century before the Kennedys. Robertson and his two cousins filled their summer evenings listening to stories about their great grandfather and about their great grandfather’s father. And what stories they were.

Robertson’s great great grandfather had been a hero in the Civil War. In 1865, he had returned to the plantation he owned in Georgia—holding a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a Bible in the other—riding in a cart. He had to ride in the cart because one of his legs was shot off.

They were a God-fearing Baptist family, and Robertson’s grandmother had to elope to marry a Methodist.

“A heathen,” his great-grandfather bellowed when he found out his daughter was in love.

“We’re all equal in God’s eyes,” she said softly.

“God never meant any man not to be a Baptist” he roared.

And that was the end of that until she defied him and slipped from her window into the night.

But the marriage turned out badly after all. Robertson’s grandfather married three more times and—as befitted a Southern gentleman—sipped a fifth of brandy every day until his death at the age of eighty-eight a few years ago.

To the children, the richness of the past and the shared struggle of the present helped make up for a half-empty stomach and wornout shirts.

“Everyone in that house was living in less than ideal circumstances,” says Robertson. “So there could be no complaints, no self-indulgence. You just did what you had to do without crying about it. I learned a lot, and one of the things I learned was that I won’t indulge my daughter. I don’t buy her things. She has a house loaded with toys. It’s far more important that I give her time—undivided time and love and attention.” He closes his eyes, as though to retreat from his guilt for making Steffie another child of divorced parents. He has actually less to be guilty about than most Hollywood ex-fathers. Unlike most of them, he spends both days each weekend with his daughter.

He opens his eyes again. “I’ve often been very grateful in a way for my difficult childhood. When I’m honest with myself I feel I’d be sitting around waiting for the world to give me what it owes me otherwise. I’ve no patience with the young actor who—because he was fortunate enough to be born good-looking—has the star role in a television series and expects the moon from now on. Most of these boys are crybabies and whiners and they have never worked as waiters or cab drivers. I have.”

It was the war that made Cliff Robertson an actor. The same war that made twenty-four-year-old John F. Kennedy a hero.

Cliff found himself in the war by accident. For one taste of wild adventure before college, he had sailed as a seaman on a tramp steamer in the fall of 1941. On December 7, 1941, the ship was bombed. The crippled ship limped to a port. They spent the next six weeks running from the Japanese and trying to make enough repairs to keep the vessel from sinking.

In his last year of high school, Robertson had decided to become a journalist. It was a choice that would please his grandmother. Becoming an actor would only anger her. But trying to keep from being blown overboard by the force of the bombs, Robertson realized that if he survived he must not compromise with his life.

He returned home to find that the freighter had been reported sunk and that his name was chiseled in stone as the first war casualty from La Jolla. The rest of his war as seaman and officer was uneventful.

His first five years as an actor, he starved. And then “it got better each year” until he was one of the dozen actors most respected in television. His career in motion pictures has been less desirable. In 1950, the studios began begging him to sign a contract. He “resisted them because I wanted to learn my craft first.” In the end, he was forced to sign a non-exclusive contract with Columbia for two pictures a year in order to get a role in “Picnic.” He feels that the studio used him as “a utility infielder,” giving him bad roles in worse pictures. And he therefore stubbornly refused enough of them so that—at the end of his seven-year contract—he still has six years to go.

He is righteously angry over this. “I’m not a young kid who’s afraid to say what I believe. I’m not interested in winning small popularity contests. I don’t want people to call me ‘such a nice boy.’ I’m interested in doing my work with dignity and doing it well. I served my apprenticeship in New York. I wasn’t picked off a drug store stool and what happened to me in Hollywood was a misuse of talent.”

As one friend of his says about “PT-109,” “It took the intervention of the President of the United States to get Cliff Robertson a good role in a decent picture. Until then directors who admired his acting and fought to star him were, instead, forced to hire ‘bigger’ names.”

Asked about the perils of portraying a man who is President of the United States, Robertson hesitates.

“If I were terribly young and terribly foolish,” he says, “it would have been very dangerous. I would be puffed with pride and tempted to take myself too seriously. I would let him take over my life more completely than as a wonderful character I’ve been lucky enough to portray.” He smiles. “But I’m not young and I’m not foolish. About as far as I’ve gone is day-dreaming about actually being able to meet the President.”

In his portrayal, Robertson tried to give, more than any one other thing, “Kennedy’s class as a man. Even my Republican friends who dislike him and voted against him respected him as a man.”

Robertson refuses to give his political views. In answer to the inevitable question he has been asked hundreds and hundreds of times in the last six months, he laughs and says, “You never asked me if I was a Republican or a Democrat before.” Then, innocently, “Why are you asking me now?”

For anyone who really wants to know, perhaps the answer can he found in Wash- ington, in Cliff Robertson’s secret file.

—ALJEAN MELTSIR

Cliff is currently starring in “PT 109” for Warners, and Paramount’s “My Six Loves.” And his next film you can soon see will be M-G-M’s “Sunday In New York.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1963