Sounds Off With Sydney Skolsky

FROM A STOOL AT SCHWAB’S:

Let’s look at the facts. Hollywood is suffering from runaway productions, and for my money the exodus just isn’t justified—even by “Exodus.” After all, why did the movie have to be made in Israel? The terrain of that country resembles that of Palm Springs. And how Eva Marie Saint looked in many scenes of that picture shouldn’t happen to a Saint. She lost fifteen pounds during the filming because of location hardships.

I’ll admit that, in the beginning, there was additional entertainment and box-office value to tour Rome in a picture like “Three Coins in the Fountain.” But long since, we have seen so much of Rome that American audiences recognize this city faster than they do Boston, Denver or even Hollywood.

I see both sides of the coin. I see why Billy Wilder had to film “One, Two, Three” in Berlin—West and East. I’m pleased he did. The story demanded it, and it gave me the chance to see much of a city that is so important in the world’s news.

It s a different story with producer-director John Huston, who’s filming “Freud” in Munich and Vienna, ‘‘actual locale of the subject.” Who’s fooling whom? Munich and Vienna have changed since Sigmund Freud experimented there. Even the couches have changed. “Freud” is being filmed in Munich and Vienna because John Huston has an anti-Hollywood complex and avoids it whenever he can.

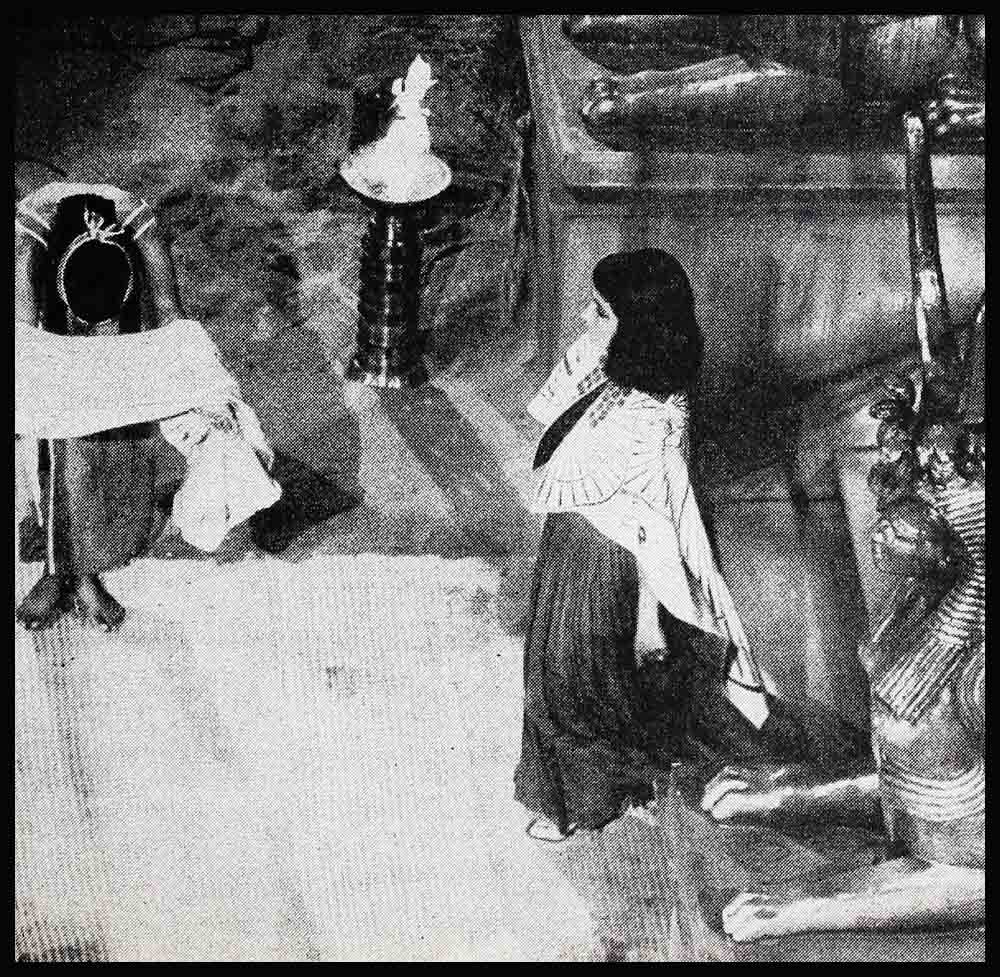

To continue. writer-director Joseph Mankiewicz is filming Elizabeth Taylor’s “Cleopatra” on sound stages in Rome. What sets built in a studio in Rome can’t be built in a Hollywood studio? None! And it would be safer for Twentieth Century- Fox because of Liz Taylor’s previous record of illness in foreign climates to make the picture here. Also, Joe Mankiewicz does his best work (“All About Eve,” “Letter To Three Wives”) in Hollywood. He hasn’t won an Oscar since he left town.

Hollywood’s ability to recreate the world on a studio stage or backlot or nearby location has been a shining example of its technical artistry. Stanley Kramer expertly interwove the real Germany with the studio re-creation in “Judgment at Nuremberg.” It is one of the finest pictures of the year.

The above-mentioned method of movie making, with few necessary exceptions, should be the American way.

The other way isn’t fair to Hollywood. It isn’t honest with the honest workers in the industry. It’s an unnecessary obstacle to those who desire to use their talents toward the expressions of our culture. It gives Edward R. Murrow’s speech a hollow sound when he asks Hollywood to make more pictures with a betler American image to send to foreign countries. This request becomes a practically impossible task because the wrong American image is already abroad where we’re making pictures for the wrong reasons.

Now let’s examine another reason: that it’s cheaper to make movies in foreign countries. Most times it is. Labor and salaries are lower, but so is the Standard of living. Kirk Douglas hired the Spanish army for a reasonable price for battle scenes in “Spartacus.” Kirk tried originally to hire the Yugoslav army but they were busy working in another movie. I’m not trying to be funny.

The lowest salary a Hollywood extra receives is $24.26. He gets this for merely showing up; there are usually extras attached to the extra’s check. In foreign countries, an extra gets five dollars—and there are no additions on the salary check. Therefore, Hollywood producers, bargain hunting, get four, sometimes five extras for the price of one here.

Yet this is penny ante. Let’s look at what happens when they play for big stakes.

Hope and Crosby made “The Road to Hong Kong” in a London movie studio. There wasn’t even the excuse of going to t he actual locale of the story. Bing and Bob’s other “Road” pictures were made in a Hollywood studio. Why London now?

The answer—The Eady Plan.

The talented firm of producer James Harris and director Stanley Kubrick filmed “Lolita” in a London movie studio. Photographs of American Street signs were flown to Harris & Kubrick so that the American city streets built on the London studio stage would be authentic. The action of “Lolita’’ takes place in this country despite the fact it was filmed in a London studio. Why?

Same answer—The Eady Plan.

How to Help the industry

The Eady Plan is a law put to work by the British government for the purpose of promoting its movie production. It has succeeded beyond original expectations. The plan is named after the man who introduced the bill in Parliament. The Eady Plan States that a minimum of a quarter of a cent is to be levied from each theater ticket sold in the United Kingdom. The collected funds are then applied as a government bonus to encourage film producers. The sums which the producers draw as a bonus for their completed and released films vary, but the average at the present time is 43% of the amount taken in at the box office.

Bluntly, “The Road to Hong Kong,” “Lolita” and other American movies were made in London (and the United Kingdom) because the American producers got a sizable portion of the production money from the British government.

France and Italy have similar plans. In West Germany, distributors usually guarantee most of the basic cost of a picture, which serves somewhat the same purpose. Almost every country in the world, except the United States, provides some kind of specific government support for its motion picture industry.

You can see that an undeclared war has existed between Hollywood and most countries of the world.

You can understand now it’s no accident that the number of movies made in Hollywood has decreased enormously.

You know now it’s not a discredit to Hollywood alone that it’s no longer the dominant motion picture manufacturer it once was.

But it can regain the title—with help.

It’s time our government not only asked Hollywood what it can do for them—a good question—but also asked what can we do for you. For instance, there’s the question of government subsidies. Our government subsidizes other industries and almost every other government in the world, except ours, subsidizes its movie industry. Why should the government do this? For one thing, it means keeping an important industry alive and healthy, with all the income—taxable—that results, and also all the jobs. For another, it means putting that industry in a position to compete with its rivals around the world. Right now, the economics of Hollywood means pictures have to be made for the largest possible audience. It means that, to get money to make his picture, a producer must have a sure thing, a formula, a star and a story that are tried and tested. With subsidies, a Hollywood producer would be in a position to compete with his French and Italian rivals, to gamble on something new, to make a picture that might not appeal to the largest audience but would certainly draw the most discriminating.

Ambassadors in tin cans

When our government goes into action, Hollywood will be able to meet the challenge of modern picture making. And only then can Hollywood be more effective presenting the American image to the world. Only then can Hollywood take its right place in this unique world; acting as our ambassadors in tin cans and communicating with the people abroad.

The problem requires more research and consideration. The government and the industry might appoint a group of men to determine whether some movie production should be subsidized. And if so how.

Perhaps the State of California instead of the national government should devise a comparable Eady Plan. This would keep the movie industry in Hollywood, California. This plan might re-elect Governor Pat Brown—if candidate Richard Nixon doesn’t beat him to it.

I believe it’s time for Eric Johnston to speak up, in Washington and Sacramento—and do something for the industry he is paid to represent. Will someone tell me what Eric Johnston has accomplished for the industry in the last five years? And the someone includes Eric Johnston.

It’s no secret that the income tax structure as applied to movie stars needs correction. There’s something basically wrong with a law that encourages artists to become conniving businessmen, within the law. by forming Capital gains corporations. You know there’s something wrong when an income tax situation gives an American citizen a huge amount of money not to live in the United States for 18 months. You also know there’s something wrong with an income tax which provides an incentive not to work. I’d like to have a non-taxable dollar for every person who has said: “I can’t afford to work any more this year, it’ll cost me money.”

There’s something so wrong it borders on evil when a law taxes an artist with- out consideration for his special talent and without consideration for him as a human being. It’s unfair to tax a movie star, a novelist, a ballplayer, a prizefighter 90 per cent during his high productive years, which are limited. This tax bracket puts him in a bind for those years to come when he is not so productive, and it comes to all men no matter how great. Yet any man who has an oil well is fortunate enough to be allowed a tax depletion. A Creative person is not this fortunate. He is expected to be a gushing well of talent forever. The human trait of depletion is ignored.

Remember, I warned you. Something’s got to be done—and now. Luckily, now is a good time. The arts have their best friend in the White House since Tom Jefferson was there. From crooner Sinatra to cellist Casals, the Creative artist gets a warm welcome from Jack Kennedy. And if anyone can take Hollywood’s message to Congress, he’s the man. If he needs one more good argument he can always try this—the Russians do it and anything they can do, we can do better.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962