6 Days Before Love Died

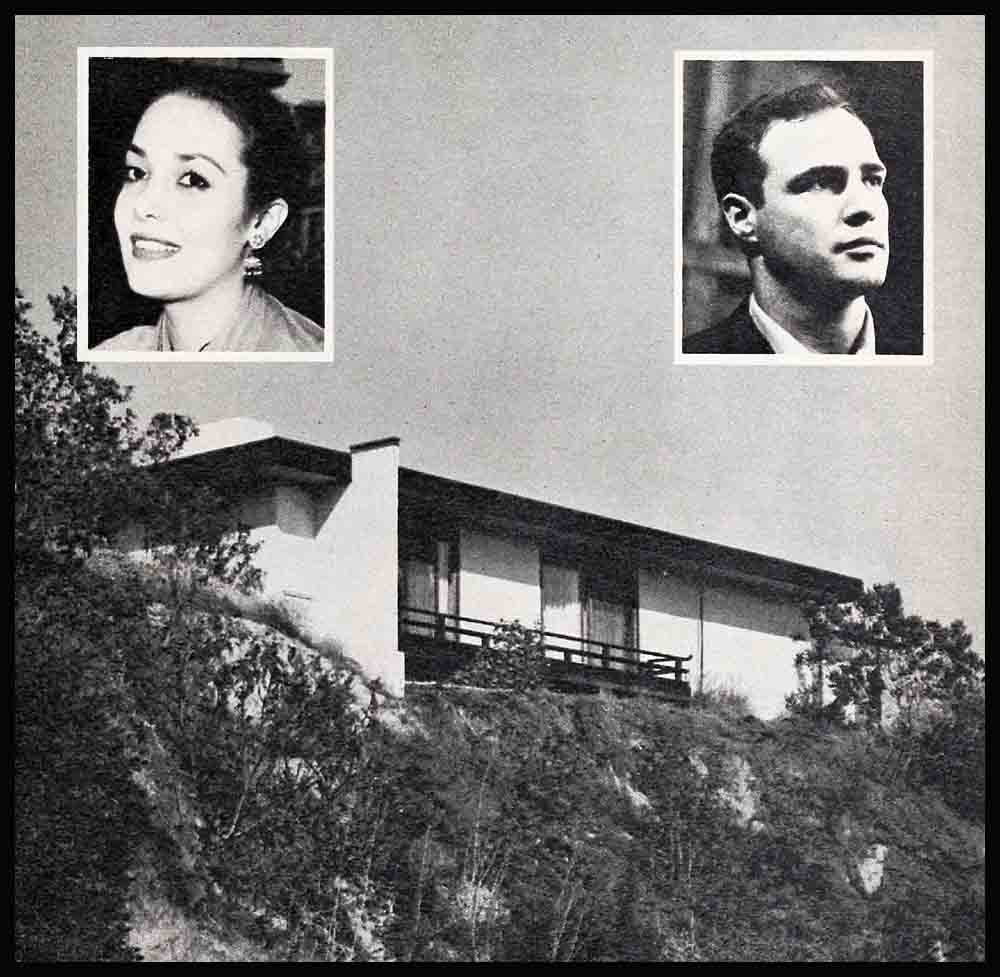

Near the end of September, just six days before Anna Kashfi Brando tearfully told reporters that her marriage to Marlon was at an end, I rang the bell at 12900 Mulholland Drive where the Brandos lived. A maid opened the door. Right behind her was Marlon himself, with his baby son, Christian, slung over his shoulder.

I looked at Marlon and he looked at me. His hair was tousled, as if he’d been romping with his child. And he seemed sleepy-eyed, with that special kind of dazed expression a father gets when he’s been pacing up and down all night trying to quiet a baby.

AUDIO BOOK

He was wearing a short-sleeved, knit T-shirt, dirty slacks and sandals. His casual-sloppy dress should have clashed violently with the dazzling porcelain and chrome kitchen we were in (I had threaded my way around Marlon’s two-door gray Ford, vintage ’53 or ’54 and past Anna’s two-door, ’58, salmon-colored Chevy, to get to the side entrance of the house; that’s why we were in the kitchen), but somehow it didn’t. Maybe it was because the baby’s bottle was warming in a saucepan on the oversized range; or maybe it was the way Marlon was jiggling the child on his shoulder; or perhaps it was just that he was relaxed and at home. Anyhow, the scene seemed exactly right.

Marlon carefully shifted Christian from his right shoulder to his left, cradling the back of the child’s head as he did so to give the maximum support. He murmured something to the baby and the infant gurgled. Marlon laughed. He motioned to the maid to take Christian into the living room. Then he turned to me.

I stuck out my hand and introduced myself. He took my hand and grasped it firmly. I explained that I had an appointment to interview his wife, and added that I’d like very much to interview him, too. For a moment he didn’t say a word. He walked over to the stove and turned the gas off under the baby’s bottle. Then he looked at me and said, “I’m sorry. I never give personal interviews.” I tried to make him change his mind, but he just smiled, shook his head no, and showed me into the living room.

At the doorway we stopped and Marlon gestured towards some soft Japanese sandals on the floor. I took off my shoes and slipped into the sandals. As I stood up again, a very pretty, dark-haired girl, Anna Kashfi Brando, came across the room toward me, sort of balancing Christian on one hip. She was wearing white shorts, a green and white striped blouse, open at the neck, and was barefoot (although her toenails were painted with silver polish). We introduced ourselves and she invited me to sit down.

Meanwhile, Marlon had gone into the kitchen and returned with the baby’s bottle. Anna had seated herself on a huge teakwood chair which had brilliant red brocaded upholstery. There was another like it a few feet away from Anna’s, at one of the corners of a large, square teakwood coffee table, and I sat down. Christian began to kick his legs and wave his arms. Marlon quickly gave Anna the bottle and she eased it gently into the baby’s mouth. They both watched the infant until it was feeding contentedly. Then Marlon excused himself and left the room.

Anna said something to me but I couldn’t hear what she said. I suddenly realized the hi-fi set was going full blast. Through the noise I gathered she was saying, “Marlon forgets to turn it off”—and I went over and flicked off the switch. On the way back, I noticed how soft and white the throw rugs on the floor were, and how highly polished the black-painted plank flooring seemed. In one corner I saw a tall pile of square pillows with Japanese symbols on them, and next to these two small, wooden headrests for guests to lean on when they sat on the pillows. But most of all, I noticed Anna and the baby, the way she gazed down tenderly at the child, the way the infant fixed his eyes on her face.

Now that the hi-fi set was no longer blaring, the soft tinkle of Japanese temple bells could be heard from the Oriental garden outside. From the living room, the rocks in the garden, with their Japanese inscriptions, looked like waves. Once in a while the babble of the little stream that ran under the bridges in the garden fused with the tinkle of the temple bells. All was peaceful, outside and inside, all was calm.

“Isn’t he a wonderful baby?” Anna asked, breaking the silence.

I nodded and said that she and the baby were something out of a painting, a Madonna and Child in a Japanese setting.

“They say motherhood becomes a woman,” she replied, smiling shyly.

“How much does he weigh now?” I asked.

“About fourteen pounds, I think. And he’s not four months old yet. He was just seven pounds, five ounces when he was born.” And then she added, proudly, with a quick smile. “But he has an awfully big appetite.”

For a while she chatted on about formulas, and sleeping habits, and breastfeeding versus bottle-feeding. “I breast fed him for about a month,” she said “It’s supposed to be better for them. But then I got upset by something. And after that I developed a kidney infection and I had to stop. I felt so close to him while I was feeding him by breast. I hated to stop.”

When she said “got upset by something,” the expression on her face changed completely, as if a cloud were momentarily passing over the sun. I started to question her about it, but changed my mind and asked instead, “And how about Marlon? Have you initiated him into the mysteries of fatherhood?”

Anna laughed. “I certainly have. He’s even learned how to change diapers. He’s a wonderful daddy. You should see him with the baby. He cuddles Christian, he plays with him, he talks to him. Honestly, there are times when he ignores me completely and only pays attention to the baby.”

Again her smile faded for a second, and then she went on. “Marlon had brought home all kinds of stuffed animals for him—elephants, dogs, cats, Teddy bears. And one enormous lion that’s several times bigger than the baby.”

The bottle slipped from Christian’s mouth. She eased it up again for him. He began to drink once more.

“Marlon gets home from the studio about seven and goes straight to the baby’s room,” she continued. “He lifts him up in the air, he tickles him, he sings and coos to him—I can’t get him out of there until the baby falls asleep. Then he first says hello to me and we have supper.”

Christian had finished his bottle. Anna raised him to her shoulder and began steadily patting his back. He made a sound that I barely heard but his mother laughed. “That does it,” she said, and perched him on her knee.

“Are you ready for nap time now,” she asked. “Are you full, little baby? Did you have enough to eat?” Christian waved his arms excitedly, trying to catch Anna’s face in his hands.

As I tagged along with Anna and the baby to the nursery, I got a quick, unofficial tour of the house. The dining room was small, with a very low table in the center where guests kneel down to eat. The Brandos’ bedroom was all done in mauve tones. The one striking piece of furniture in it was the large, Emperor-size, double bed, low to the floor, with a delicately carved, ivory panel fitted in the headboard. The nursery itself was a converted den where Christian was separated from his parents’ bedroom by screens. In fact, the entire house was filled with these beautiful hand-painted Japanese screens. They were lovely.

Back in the living room, after the baby had been put to bed, we talked about Marlon. “He loves children,” Anna said, “he loves them very much.” For a moment she stopped and looked out at the garden. We could both hear the temple bells ringing in the Japanese dwarf tree. Then she continued, but the tone of her voice had changed. Perhaps it was just my imagination, but I don’t think so. Now it was a little pensive; yes, and a little desperate. “We hope to have more children. Boys and girls. Lots of them.” And then her voice trailed off almost to a whisper.

She changed the subject abruptly. “Marlon lets me do anything I want,” she asserted. From the way she said it, I couldn’t tell whether she was pleased about this, or complaining. Then she went on to talk about a variety of things: the role she was playing in a new M-G-M picture, “Night of the Quarter Moon”; the way newspapers handle stories about Hollywood marriages; the stupidity of racial prejudice; and much more. But all the time she was talking, skipping from one topic to another, I had the strange feeling that she was talking at me and not to me, that somehow she just wasn’t there. Once she jumped as she heard the sputtering sound of a car starting outside. “It can get so lonesome up here,” she said. “I can never get used to it.”

The maid interrupted us by bringing in some Japanese green tea. It was very good.

When we’d finished, Anna returned to her “loneliness” theme. During the summer, while Marlon had been busy making “One-Eyed Jacks,” a picture in which he stars, and which he has largely written, directed and produced himself. Anna had taken a course in Philosophy at U.C.L.A. She rode to classes with Phyllis Hudson; and Phyllis was a frequent caller at the Brando home, offering Anna companionship when Marlon was away.

“The philosophy course was fun ” Anna said, “and I hope to take more. If I’m not tied up on a picture—and of course, if I’m not tied down too much with the baby at home—I’d like to take other classes.”

But this was getting far away from Anna and Marlon, so I asked, “Do you and Marlon have a chance to get out much now?”

“We can get out occasionally,” she said. “Did I tell you about our visits to the new ‘beat generation’ hangouts?”

It seemed she and Marlon had recently visited two of these sawdust strewn clubs, one, called “Cosmo Alley,” in a Hollywood back alley, the other, “The Unicorn,” on the Sunset Strip.

“I saw all those girls with their long, dirty hair, and with tons and tons of black eye shadow. And we saw one skeleton-like old man reading poetry to a jazz background. He looked like he was dead.”

“You don’t dig this ‘Beat Generation’ then?” I asked.

“Not at all. I think it’s a lot of hooey. As far as I’m concerned, what those ‘beats’ seem to need most of all is a good bath.”

Anna sort of shuddered as she said this, as if the memory of the “characters” in the “beat dives” was something very distasteful to her.

“What about Marlon?” I asked. “Does he dig that kind of people?”

For a moment she hesitated and then answered, “I don’t think so. No, I’m sure. He doesn’t like them.” The way she said it, it sounded like she was trying hard to convince herself.

It had grown dark outside. In the kitchen I could hear the maid preparing dinner. There were no sounds from any other part of the house. Just the bustling in the kitchen and the soft tinkle of the temple bells outside.

Anna walked with me to my car. The ground outside the house was still hot, but it didn’t seem to bother her, although her feet were still bare.

She stood near my car for a moment, looking up at the wild hills that surrounded her house. “Do you know,” she said, “I think we have mountain lions or bobcats up here in these hills. I can hear them screaming at night.”

“Do they frighten you,” I asked.

“Not when Marlon is here,” she answered. “I’m not scared when Marlon is here.”

We both looked over at the parking area, Anna’s Chevy, with a baby seat hooked over the back of the front seat, was still there. But Marlon’s Ford was gone.

I said goodbye and Anna turned away. As I swung my car around, the headlights shone directly on her for a few seconds. She seemed very small, suddenly; small and helpless.

In the next few days I tried twice to write the story of that interview with Anna Kashfi Brando. The theme was always the same, the happiness of a wife and mother, but somewhere along the line something always went wrong. Little things Anna had said . . . and the memory of the expressions of sadness and strain that had flitted across her face . . . blotted out what I was trying to put down on paper: “But then I got upset by something” . . . There are times when he ignores me completely” . . . “Then he first says hello to me” . . . “It can get so lonely up here. I never get used to it” . . . “I’m not scared when Marlon is here.”

Then, on the morning of September 30th. I picked up the morning paper and read the headline: Anna Brands Brando Truant Hubby, Quits. The story said that Anna was suing Marlon for divorce. “This is final,” she declared. “I can no longer take his indifference and neglect and his strange way of living. I will charge desertion and cruelty.”

The article went on to state that Anna had lost much weight—she was down to 100 pounds—and was taking tests for a heart condition, which she maintained Marlon knew about.

“Naturally, in my present condition I’m frightened. To whom but my husband should I turn for comfort. But how can I—he is never there,” she added.

I called the Brandos’ private number at their house on the hill at 12900 Mulholland Drive, but it had been disconnected. From friends, I learned that Anna was staying at Phyllis Hudson’s house, but I was unable to reach her.

As for Marlon, no one knew where he was. And besides, it was almost certain that he wouldn’t talk about his personal troubles.

Nevertheless, just on a hunch, I drove over to The Unicorn, one of the “beat” joints that Anna and Marlon had visited together. I walked up a single step into a small room. It was very dark inside, the only lights being from candles on the four tables that lined one side. The walls were covered with modern paintings—mostly nudes and clowns. A young fellow with a crew cut was playing on an upright piano. The tables were crowded—fellows with beards and girls in leotards—and the place was filled with music, talk and smoke.

The piano player told me that Marlon used to come here pretty often when the place first opened but that he doesn’t come any more. I sat down at one of the tables—it was early and there was still room to sit down—and ordered Italian coffee and pastry. A young fellow in faded blue jeans and a black sweater sat down next to me.

“Heard you ask about Marlon,” he said. “What do you want with him?”

“Just trying to find out where I might get in touch with him,” I answered. ‘I want to ask him some questions.”

“What kind of questions?” he asked.

“Questions for an article I’m writing,” I answered.

He laughed. “Oh, that kind of questions. Give up. Even if you catch up with him, he’ll never answer you. Why don’t you ask me about him? I used to know him very well. But let’s get out of here and go where we can get a drink.”

So we went to Cosmo Alley, the other “beat” club that Anna and Marlon had gone to. We entered through a narrow alley, and although it was on the street level, I felt like we had gone down into a murky cellar. The main room was jammed with tiny tables, four chairs to the table, and most of them were filled. The lighting was just as poor here as it had been at The Unicorn, except that it came from orange colored discs hanging from the ceiling. The main wall was of red brick, on which a mural had been started and left unfinished.

We sat down and my new-found friend ordered wine while I asked for a beer. The waiter disappeared through a hole in the wall, a hole that looked like it had been made by a cannon. In a still smaller room in back I could see a jazz combo playing. The noise ws deafening.

“Marlon digs this place the most,” my companion said.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Everybody calls me Ned,” he answered. “That’s not my name but it’ll do. You’re probably wondering if I really know Marlon or whether I’m just trying to mooch drinks from you. Well, I do know him and I am trying to mooch drinks.” And then he started to tell me about Brando.

As he talked, recalling first the old days when he had first met Marlon in New York, telling me about the parties they used to go to in Greenwich Village, filling me in on the details about Marlon’s early days in Hollywood, and bringing me up to the present, any doubt I had about whether Ned really knew Marlon faded. And in trying to find out what had gone wrong between Anna and Marlon, a few things Ned said stood out above all the rest.

Marlon wasn’t a “beat” character, Ned declared. He had been attracted by the way the poets and the would-be actors and the artists and the folk singers were trying to live their own lives, trying to remain individuals in a world where everyone was becoming more and more like everyone else. But Marlon had found, Ned said, that there were as many phonies among the “beat” characters as there were among the people who made moving pictures. And their protest against society, their rebelliousness, was all out of the same mold, as predictable as were the habits and the actions of the most conservative pillars of the community.

So Marlon had come, had seen, and had walked away. Not back to conformity, not back to ease and comfort, but to his own private, desperate fight to find meaning in the world around him.

Marlon’s a great guy,” Ned said. “Warm. Friendly. Sympathetic. But he’s as sensitive as the litmus paper we used to use in chemical experiments in high school. You know the stuff. Just a tiny change in the temperature and it reacts. That’s Marlon. He’s tortured by himself. He seeks perfection. And in this crazy, beat-up world he’ll never find it.”

Ned swallowed a glass of wine at one gulp. “I’m sure Marlon loved Anna in the beginning. Maybe he still loves her. And I know he’s crazy about his kid. But he’s not a pipe and slippers kind of guy. He’s always searching for something: new people, new ideas, new places, new answers to old questions, new answers to new questions. He gets a bee in his bonnet and just takes off. For a woman to love Marlon is okay; for her to want to tie him down and housebreak him is impossible. He’s too restless, too driven. He’s . . . he’s . . . well, he’s just Marlon.”

A girl came up to the table, a pretty girl with black bangs and a bright red sweater. “Ned, honey.” she said, “you’ve been ignoring me. Let’s you and me dance.”

He lifted the whole bottle of wine to his lips and gulped it down. Then he got up to dance.

“That’s all there is, poos,” he said. “There is no more. A guy that can’t ever find peace within himself—that guy should never marry. A woman doesn’t change a fellow like that. Nothing changes him. He’s gotta keep running round in circles. I know how it is. And I’m sorry for him. I’m sorry for Marlon.”

And then he and the girl danced away and the jazz seemed to get louder until I just had to get out into the air.

“Poor Marlon,” I thought, “poor Anna, poor Christian.” And then I went home to write my article.

THE END

MARLON WILL SOON APPEAR IN PARAMOUNT’S “ONE-EYED JACKS” AND ANNA IN M-G-M’S “NIGHT OF THE QUARTER MOON.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1959

AUDIO BOOK