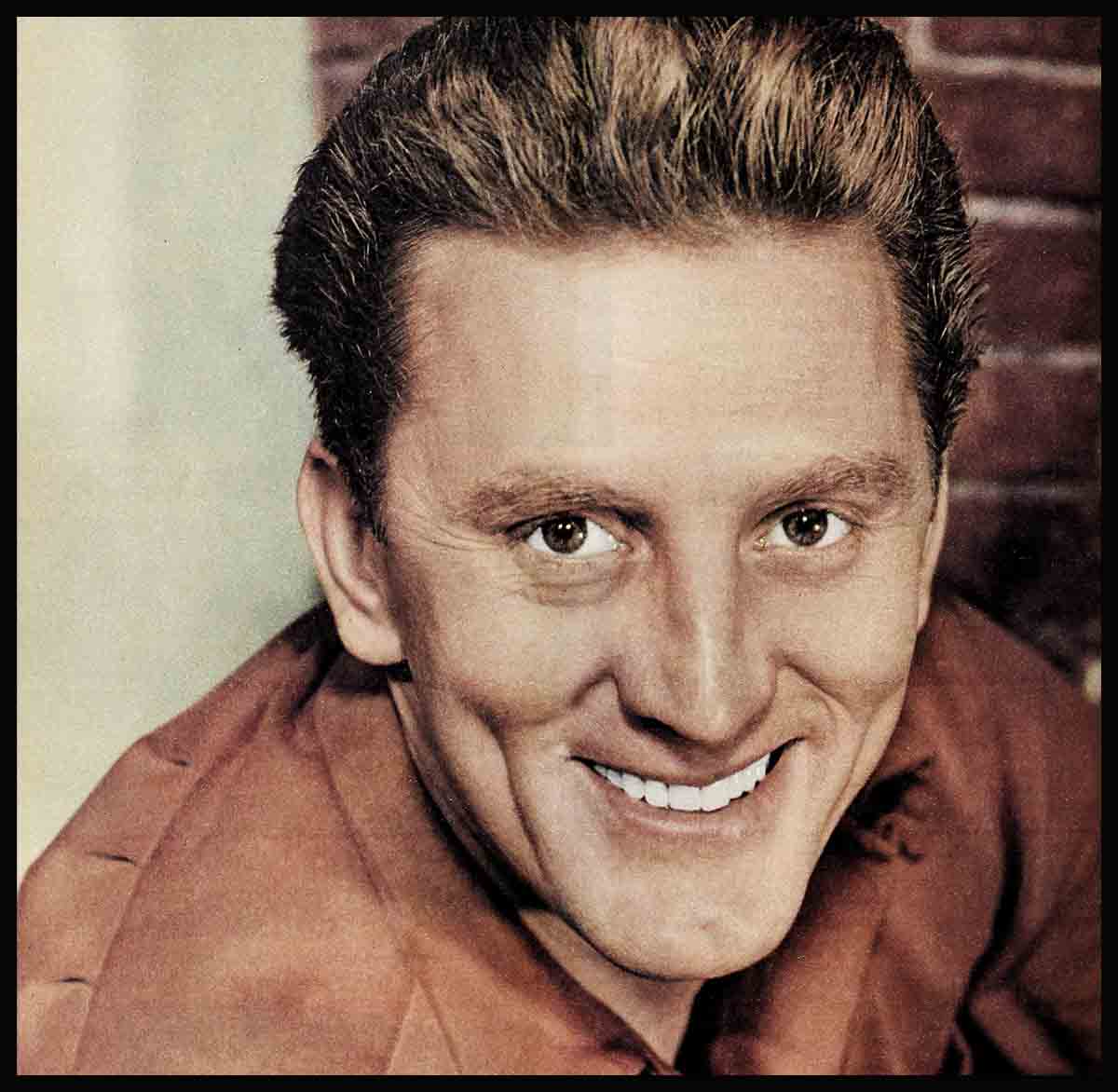

There Was A Boy—Kirk Douglas

A mother dreamed a dream for her only son. The boy lived it out, until the dream was reality. . . .

“Funny about dreams,” says Kirk Douglas, for he was the boy, and the dream was his mother’s, “something happens to them when they come true. Something is left out. You get what you’ve always told yourself you wanted out of life, you achieve what you’ve driven yourself all your days to achieve, and it isn’t good enough.”

He faces up to himself these days, Kirk Douglas the motion picture star, the potential millionaire the embodiment, in fact, of the classic American Success Story, and asks himself why it all doesn’t add up to happiness. It was supposed to.

“Have I been kidding myself?” he wonders. “Did I want something else all along? If I did, what was it?” Nobody but Kirk can answer those troubled questions. But it is possible to understand them, knowing his whole story.

A motion picture called “Champion” last year made Kirk Douglas a star.

His was not a new face in Hollywood, but there was something about his remarkable portrait of the fighter to whom nothing was important except to win. He played a vicious man with such insight that audiences, understanding Midge Kelly, pitied him. There was no question, after “Champion,” that Kirk Douglas had arrived as an actor. He warranted and he received the tokens Hollywood awards its own champions, the furore in the papers, the star on his dressing room door, the million dollar contract.

His “arrival” also was accompanied, and this is not so unusual in “success” stories either, by heartbreak: Separation from his beautiful actress-wife, Diana; troubled concern for the future of his two young sons; doubts of his own capacity for happiness.

“Could be,” Kirk says, “that the pot at the end of the rainbow is always filled with more ashes than gold, but I don’t want to believe it.”

Kirk’s story began, actually, eight years before he was born. The year was 1908 and Kirk’s mother, Bryna Danielovitch, an unschooled Russian peasant girl, was en-route by steerage to America.

Life in old Russia had been hard for Bryna. There had been no money, little food. Her husband, Herschel, had been conscripted into the Czar’s army.

Herschel was a born rebel, his son says, “a rebel without a cause,” and life in the army proved intolerable. He deserted and escaped with a price on his head, to the United States.

Bryna was on her way to join Herschel in their new home, in the New World, in Amsterdam, New York.

Her throat ached with excitement, she reached out eagerly for what she confidently expected would be a new, free life.

In America, Bryna Danielovitch knew things would be different. America was the land of opportunity. There would be honest work for Herschel and enough to eat and her children, when she had children, could grow up proud and free. They could learn, as she had never been permitted to learn, to read and write, they could go to school, even perhaps to college. They could Be Somebody.

That was the beginning of the dream. Things didn’t turn out exactly as she had expected. Herschel Danielovitch, transplanted to America, became Harry Douglas, American, but he was still a rebel. Most of the men who lived in their neighborhood, in the oldest, shabbiest section of Amsterdam, worked in the carpet mill.

But Harry found the factory too confining.

He liked to be out of doors, he liked to be free to sit around with his friends over a beer in DiCaprio’s Diner.

He worked, made a little money. He managed after awhile to buy a cart and some horses, and he eked out a living, peddling junk, peddling fruit in the summer, hauling logs in the winter.

Children arrived at two-year intervals after Bryna came to Amsterdam, three daughters, Betty, Katherine, Marion, and, in 1916, a son, Issur. And three more daughters, Fritzie, Ida, Ruth.

The family paid a small down payment on a big enough, if beat up, old house. That house was finally paid for, free and clear. But one of the first things Kirk Douglas did after his Hollywood triumph was to make it possible for his father, by that time the only member of the family still living in Amsterdam, to live comfortably in a new, modern house. Harry is alone in Amsterdam, but he is not lonely. His house is new, but still within easy walking distance of DiCaprio’s Diner.

The poverty of that immigrant family would be inconceivable to most of Kirk Douglas’s friends today.

“There was never anything in the icebox . . . sometimes nothing but a can of cooking oil, the smallest size,” Kirk recalls. “It drives me crazy today, if the refrigerator at my house isn’t crammed with food. I have a complex about food. Even if I go to a fancy dinner party, or an expensive restaurant, I feel I have to eat everything on my plate. I can remember too well when there simply wasn’t enough to eat.”

His mother was mere successful than most women in her position at feeding her big family.

“She had a peasant knack,” her son says, “of making something wonderful out of a bone and water and salt and pepper.”

She made lunches every morning for the children to take to school, for they did go to school, that much of the dream was materializing.

“She would put a few drops of oil in the largest frying pan,” Kirk says, “beat a single egg with water, spread it out as thin as she could and divide it up among us for sandwiches.

“I used to see the other kids at school, eating sandwiches with chicken and butter and mayonnaise and lettuce, and I wanted to grab them out of their hands.”

It is not surprising that Kirk’s first present to his mother after his early stage success was a modern refrigerator, filled with food.

Kirk’s oldest sister, Betty, quit school after the ninth grade to go to work to help support the family.

“I know now that she must have resented it,” he says. “But somebody had to. Mother couldn’t go on like that.”

As a little boy, Kirk didn’t sense the steel strength beneath his mother’s gentleness. Strength, to him, was embodied in his father. His father was Superman.

“Father never picked a fight in his life,” he recalls, “but if somebody challenged him, and somehow or other he managed to get himself challenged every night, he could lick his weight in wildcats.

“I admired that. I guess I rather admired his rebellious spirit, too. There’s certainly a large slice of it in my own character. I don’t think rebellion is necessarily bad. My father could have been a great guy, with half a chance. He could have been a tremendous actor.”

Kirk had his half a chance. saw to it.

Not that he didn’t work for it.

He started working before he started to school, “running errands for the guys down at the mill.” When he was seven he was in business. I bought up pop and candy and sold it, from window to window at the factory. Those mill hands still remember me. When I go back to Amsterdam to visit my dad, they come up to me on the street and shake hands. ‘You sure were a skinny little kid,’ they tell me.”

He was skinny, all right, and not just because he didn’t get enough to eat. He drove himself mercilessly from the first. His mother’s dream had communicated itself to him, and he was committed. He ‘had to Be Somebody.

When time came for him to go to high school, the family held a conclave.

“I could have got a job,” Kirk knows. But his mother wouldn’t consider it. Her son was going to school. And college.

He enrolled in the Wilbur H. Lynch High School, without telling his teachers about his outside job.

Those years he was up at five a.m. every morning, to meet the New York trains, pick up and deliver the big city newspapers. He had just time enough, after his route, to get to school, often without breakfast. After a full day in classes, he went back to work, this time to deliver the afternoon papers. This took until 7:30. After a bite of supper, he was too tired to study.

He landed once in the office of the school principal, Louise Livingston. He had failed to turn in a book report on “David Copperfield.” Miss Livingston questioned him about the book, he described it in the greatest detail He had read it years before, at home, aloud, to his mother.

By this time, Kirk had taught his mother to sign her own name. When he rode in the streetcar to the Temple with her on Saturdays, he would see that she was straining, through her thick glasses, to see all the signboards they passed.

“What are you doing, Maw?” he’d ask.

“Issur,” she’d say, painfully spelling out the letters, “what spells C-R-I-S-C-O?”

“Crisco, mama,” he would tell her. “It’s a kind of fat, for frying.”

“What a wonderful country,” Bryna would sigh, sitting up straight and proud. His mother, Kirk Douglas believes, is the greatest American he has ever known.

His father was Superman, but his mother was a great human being. “She never did learn to read,” he says, “she tried to go to night school, but it was too much after her long day’s work. Nevertheless, all her life, people with ten times her schooling have sought her out for help with their problems.”

Kirk made friends in high school. He met boys and girls whose backgrounds had been quite different from his. They invited him to their homes.

“Hey, Maw,” he would shout, coming home from one of those visits, “I’ve been to Jerry’s house, and what do you think? He has a room of his own! And do you know what else? They have sweet rolls with their meat!”

There was no high school activity (except for sports, his job ruled that out) which Kirk didn’t try out for and excel in. Dramatics, of course, “acting is a kind of escape, in one way,” he says, “you can play out your dreams, believe for a little while that you are what you will be really someday, if . . .”

If you never stop running.

Kirk was Lynch High School’s best actor. He led assemblies, won oratorical contests, recited poetry in classrooms.

When he was a senior, he was president of his class, manager of the year book, an editor of “The Item,” the school paper.

He didn’t always get to his classes.

Miss Livingston, his principal, recently recalled one crisis, late in his senior year. Kirk was facing a test in history, covering two weeks’ class work he had missed. If he failed the test, he wouldn’t graduate. She corralled him, for by now she had made this particular student’s problems her own intense concern, shut him in a room alone for two hours with the history book. He passed the test.

Commencement came at last. Kirk directed all the Class Day exercises, polished the manuscripts of will and prophecy, rehearsed the graduates in a class song he had composed, presented himself with the others for the precious diploma.

He got his diploma, plus a cash award for first place in the essay contest, a cash prize as winner of the oratorical contest, and the Dramatic Prize for the best performance of the year in a school play.

“You know,” Kirk confided to Miss Livingston, after it was all over, “I made money on commencement.”

Money, not the play, was still the thing.

Kirk had been offered a scholarship at St. Lawrence University, but he felt he shouldn’t take it. His sisters had all passed up college to take jobs. “It’s so much harder for girls, to work their way through, they have to have clothes, and things.”

His older sisters had married, and had responsibilities of their own. There was a place for any money Kirk could have earned. But his mother and sisters would not hear of his quitting now, “when you come so far.”

“They gave me my freedom,” he says. “Mother loved me too much to hold me. My sisters never said ‘he’s a man; why can’t he support the family?’ It’s an obligation I can never repay.”

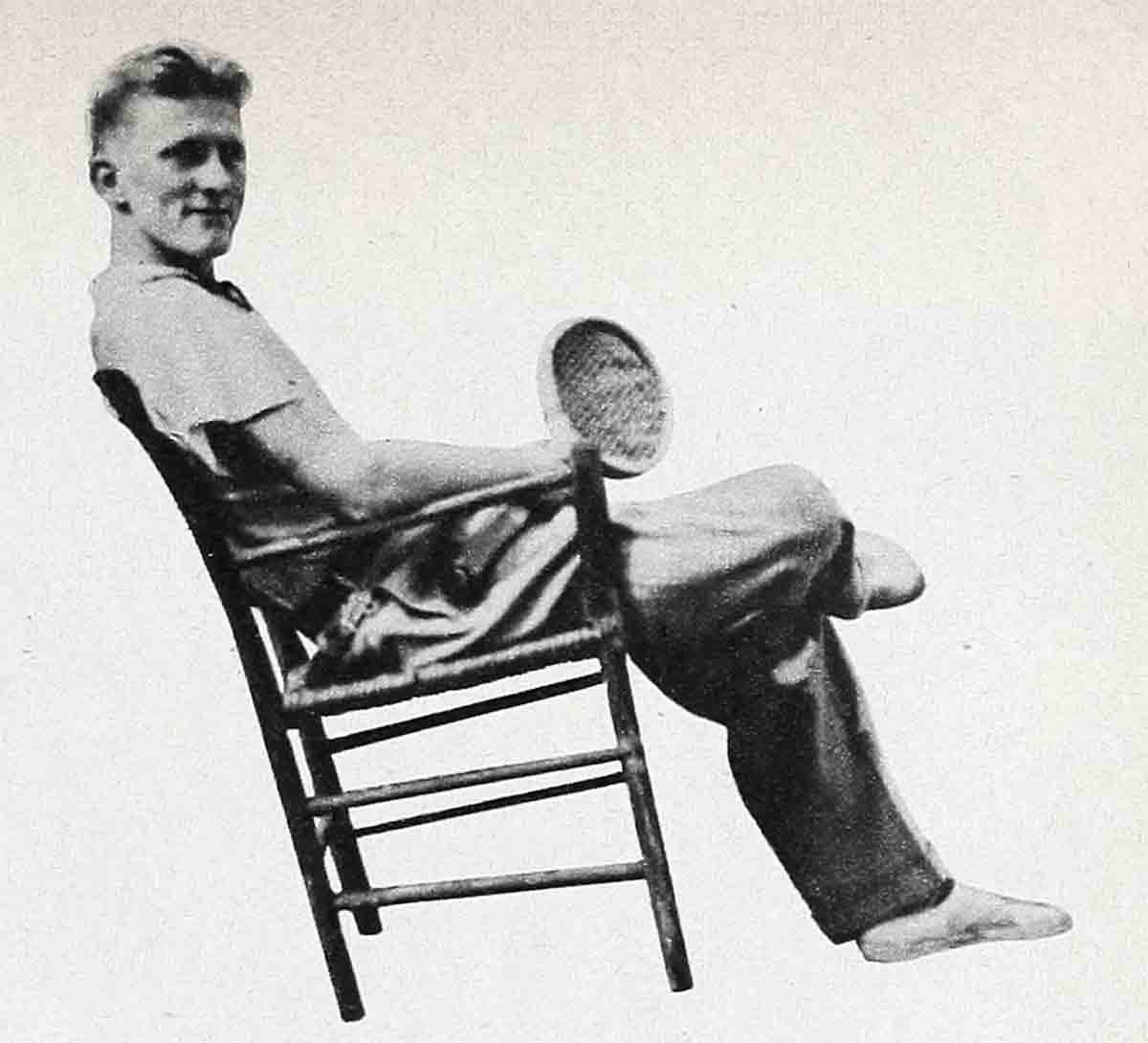

Kirk arrived at St. Lawrence University, ingloriously, since his frugally hoarded $183 didn’t provide for trainfare, riding on top of a truckload of fertilizer.

He attended to first things first. He got a part-time job as a waiter, to cover his living expenses. For the first time, he went out for sports.

“I felt I needed that,” he says, and not just because he still envied his father’s physical prowess. “A guy like me—with a mother like mine, and six strong sisters, who had never had his hands on a baseball bat, or learned to kick a ball, would have been awfully easily dominated. I guess I was afraid of accepting a feminine set of values.” He needn’t have worried. Within a few months he was the college wrestling champ, and good enough to make vacation money the next few summers as an exhibition wrestler in a carnival. “Champion” was not just acting, Kirk can fight.

The fighting he learned. The acting was there. Part of him; his escape, his safety valve.

At St. Lawrence, he plunged with all his compulsive energy into the college dramatics program. His sights shifted upwards. “If only I could be an actor, a professional actor . . .”

The pretty coeds whom Kirk dated in the rare hours when he was not rehearsing for a play, pounding a mat in the gym, or toting a tray in the dorm for eating money, found him exciting company, but mercurial.

He had no urge yet for a “steady girl,” no time for serious romancing. He still had a long, long way to go.

When he was a Junior he managed a holiday trip to New York, where he presented himself to the director of the American Academy of Dramatic Art.

“I will finish college in one more year,” he explained, “and I want to study here. There’s just one little hitch . . . I haven’t any money.”

Why, he was asked, had he decided on the Academy. There were other dramatics schools where scholarships were available.

“I want the best,” said the nineteen-year-old stalwart.

He read for the director, who admitted, “You are a talented boy.

“If you still want to come here when you’ve finished school,” he told him, “there will be a place for you.”

His family received with joy this new proof that their white hope was extraordinary.

When graduation time finally. came, Bryna framed her son’s college degree and hung it in the place of honor in the home, in Albany, where she lived now with Fritzie and Ruth and their families.

When Kirk sweated out his last summer job as a punch operator, his family prepared for the momentous leave-taking.

They bought him presents, books of plays and poetry he loved, warm sweaters for the cold New York winters.

Kirk’s sister, Kay, saved enough from her stenographer’s salary to buy him a suitcase embossed with his initials.

A college pal gave him an overcoat. It was frayed, and sizes too big for him, but it was warm. He wore it all the first winter at the Academy.

“I pretended I liked my coat flapping around my ankles,” he recalls. “I got by by being a character.”

A girl he met at the Academy, Betty, now Lauren Bacall, saw through his ruse, pried a coat for Kirk from a wealthy uncle. “I was touched,” Kirk says, “and a little ashamed.”

He met another girl at the Academy, a girl who moved him as he had never allowed himself to be moved before. Her name was Diana Dill, the daughter of a British government official in Bermuda.

“Diana had something I admired and envied,” he says, “I guess you would call it breeding.”

Diana’s background and comparative affluence had not made her a snob.

“Diana is the most liberal-minded person I’ve ever known,” Kirk says of her now. “I was always for the underdog, of course. I am the underdog, or rather, I keep forgetting, I used to be. Diana reached the same point of view intellectually.”

They saw one another in class, and they were aware of one another in Schraffts’ where Diana was a patron and Kirk, still earning “eating money,” was a waiter.

But their relationship did not proceed beyond the “I’ll treat you to a soda if you have a quarter” stage because Warner Brothers offered Diana a contract, and she abandoned New York for Hollywood.

Kirk completed his training at the Academy in 1938, the year of the recession, and for awhile it looked as though his dream of becoming a Professional Actor would have to be modified to read Professional Bellhop.

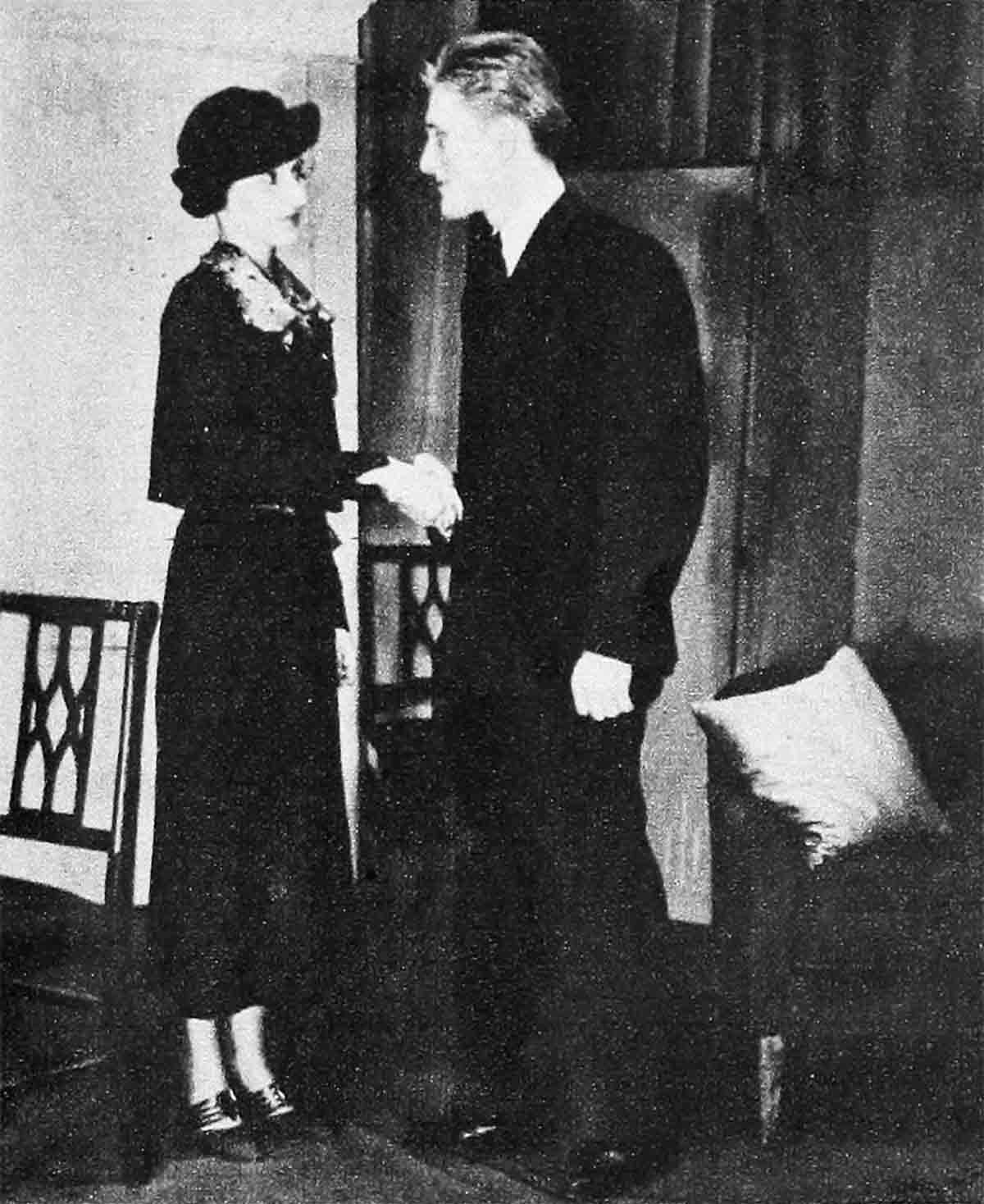

His acting achievements that first year of this tussle with the Goliath of Broadway were the role of a singing messenger boy in “Spring Again” and an off-stage echo in “The Three Sisters.”

“Kirk is in a play with Katharine Cornell,” Bryna Douglas could tell her neighbors.

“In the wings, Maw, in the wings,” her son would have added, had he heard her.

But the next year, Kirk caught up with The Dream. He landed the juvenile lead in the comedy smash hit, “Kiss and Tell,” replacing Richard Widmark.

The skinny kid of Amsterdam had conquered Broadway. He could set his sights on the last goal his ambition required of him: Stardom.

But the war came, and he enlisted in the Navy.

In a barracks at Notre Dame in 1942, where he was with an anti-submarine unit, a sailor hurled a copy of “Life” in the air with an awed “What a dish!”

Kirk looked at the girl on the cover. It was Diana Dill, now a New York photographers’ model.

“I know her,” said Kirk, suddenly homesick for the city, and his old friends, and the theater, particularly for Diana.

“He knows her,” his buddy scoffed.

“But I do,” Kirk insisted.

He wrote to her that night, asked her to save a date for him on his first furlough. That furlough was like nothing Kirk had ever experienced before.

He was newly an ensign, with a resplendent new uniform.

He had $189, more “eating money” than he had ever had in his pocket at one time.

Diana looked like a dream.

“Much too good for Schrafft’s,” he said, and he whirled her off on the biggest night of both of their lives. They had dinner at the Starlight Roof, saw a play, sat at a front row table at the Copacabana, rode the length of Fifth Avenue on a bus top, held hands, and then, strangely moved and shaken, said goodbye.

The $189 was gone. Kirk had to borrow money from friends to get to Albany.

Kirk, his furlough over, was ordered to New Orleans. Diana’s modelling job took her to Phoenix for desert fashion pictures.

New Orleans was on her way home, sort of. She never got home,at least for a month, for on the third day of her visit in the old French city, Diana and Kirk were married by a Chaplain in the Naval Chapel on the post with Kirk’s fellow officers in attendance. The ring was Kirk’s sister Marion’s, air-mailed for the ceremony.

Their swift romance, the romantic marriage, “all pure dream stuff,” Kirk recalls almost wistfully.

At the end of the month Kirk shipped out for the South Pacific. Diana went back to New York. They wrote every day, but letters were slow moving then. It was months after Kirk was seriously wounded that Diana heard he was in a hospital, waiting for his medical discharge. And Kirk was in that hospital before the news reached him that he was soon to be a father.

Michael Douglas’s first impression of his father must have been of a man who slept until noon and stayed out late, for by the time he was born Kirk was back on Broadway. They had settled down in quaint old St. John’s colony on Eleventh Street, and life was good. There were times when there wasn’t enough money. He appeared in “Alice in Arms,” but it ran only briefly. The occasional radio jobs with which Kirk tried to balance the budget were too occasional, sometimes.

There was always Hollywood, but Kirk and Diana had ruled out Hollywood.

Tinsel and sham, they agreed, in chorus with many other serious young actors.

Kirk was content to Be Somebody in the Theater.

When Kirk landed a part in “The Wind Is Ninety,” and faced the usual three weeks’ rehearsal period, he agreed that this was an opportune time for Diana to take little Michael to Bermuda for his first visit with his grandparents.

“The Wind Is Ninety” closed after a few months’ run, but not before Producer Hal Wallis, who had been urged by Lauren Bacall to have a look at her old friend, Kirk Douglas, saw the show and offered Kirk a film contract.

“I don’t want to go to Hollywood,” Kirk told him, “I’m afraid of the place. But I’m broke, and in no position to deliver a lecture on integrity.”

He wired Diana and Michael from his westbound train, “Get me. I’m on my way to that awful place called Hollywood.”

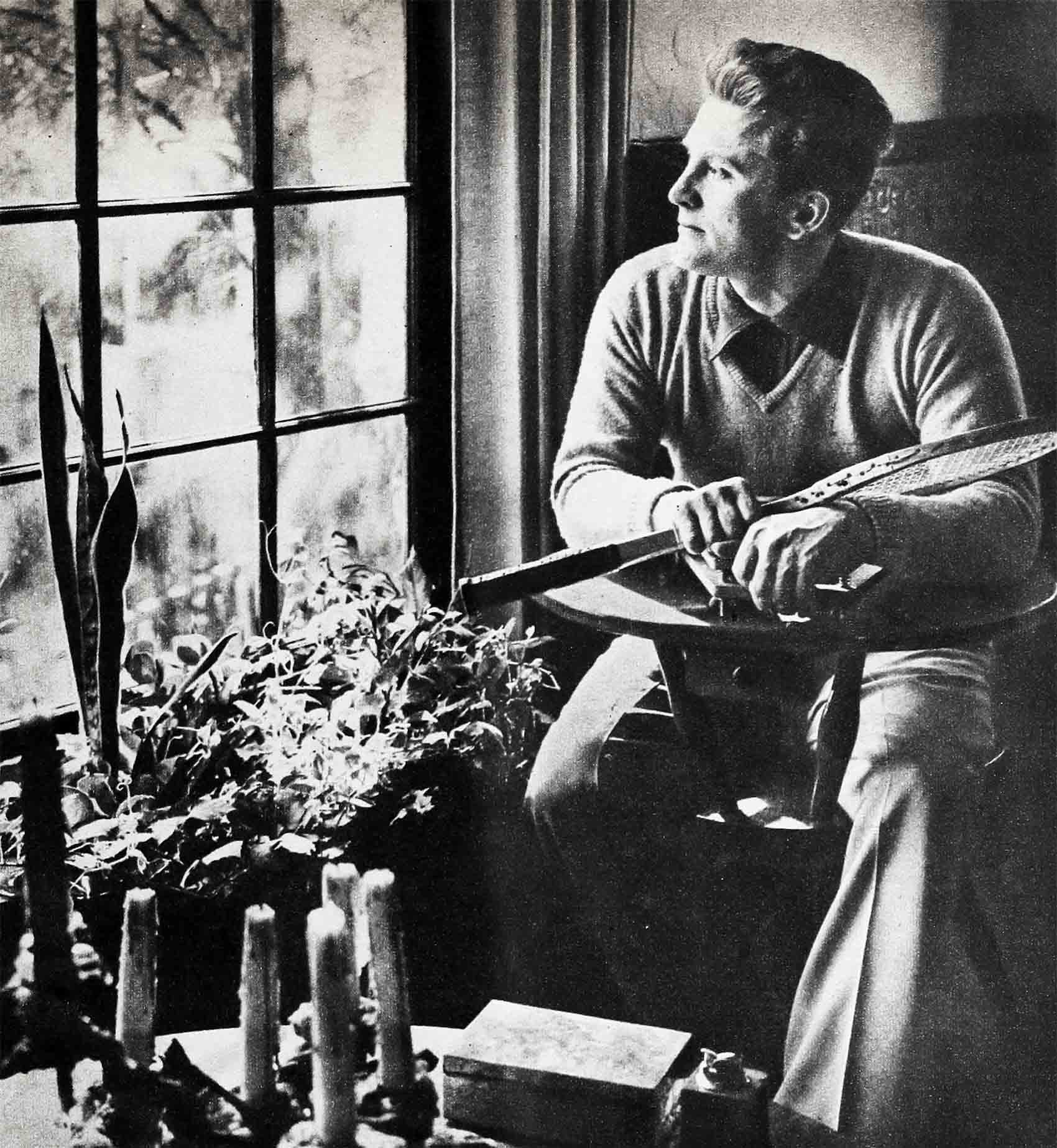

Kirk didn’t go soft in Hollywood. He worked as hard at keeping his “values” as he did at his first juicy part as Barbara Stanwyck’s alcoholic husband in “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers.”

He and Diana bought a seamy old house “with atmosphere and rusty plumbing,” in an unfashionable section of the Hollywood Hills. He cleared an acre of hilly, overgrown land with his own hands.

A new baby was coming, so Kirk had to build an extra room. The hills resounded to the clatter of a cement mixer and saw and hammer every Sunday.

Kirk made one picture after another; his work was distinguished, but not yet star stuff. Diana, when their second son Joel was a few months old, had a fling at pictures, too, and did very well in “Sign of the Ram.”

Came “Champion,” but not easily.

It was to be the initial film-making effort of a new and untried, skimpily financed producing company. Its producer, director, and writer were comparatively unknown. The cast, except for Kirk, was equally uncelebrated.

Kirk’s agent and advisers were unanimous in insisting that he turn the offer down. He protested in vain that the story was good, the part was great, that it didn’t matter if the picture had to be shot in three weeks at a budget of less than a half million dollars. He protested in vain, that was, to everyone except Diana.

“It’s your big chance,” she said, “you’ll be awfully sorry if you don’t do it.”

“Champion” was, of course, an immediate sensation, and it catapulted everyone connected with it into the top money brackets in Hollywood.

As for Kirk, he had done it now. The dream, at last, had come true.

“This is it,” he said. “This is what I’ve always wanted.”

He was rich and famous now. His mother could come out to visit them.

“What a kick she’ll get,” he said.

But Bryna was not well enough to come; she had had a heart attack.

Kirk rushed east to visit her, and his sisters. He went to Amsterdam, too, to see his father, joined him on his nightly pilgrimage to DiCaprio’s diner.

Harry presented Kirk proudly to his old friends. “This is my son, Kirk Douglas, of Hollywood,” he said.

And the bartender, after wiping his hands on a clean white towel, shoved out a fist. “I’m glad to know you,” he said.

But he had known him for years. He was that skinny kid, remember?

The uneasiness he felt there stayed with him, even after he returned to the warm, homey house on the hill in Hollywood.

Diana was restless. He career was at a stalemate. It enraged Kirk that he, that she, now that all the old problems were solved, the old insecurity gone, should be unhappy.

The refrigerator was full, wasn’t it?

There was more to life than work, wasn’t there? Didn’t they marry to have a home, a family . . .?

“But,” said Diana, “I have my ambitions, too.”

Her dream, too.

Kirk understood. He almost understood.

“The Kirk Douglases have separated.”

The item in the papers was so usual, so unsurprising in Hollywood, that no one paid much attention. Except the Douglases. The four Douglases.

And probably, back in Amsterdam and Albany and Syracuse, the seven women, who, before Diana, had been the only really important women in Kirk Douglas’s life.

“It wasn’t just ‘career trouble,’ ” Kirk declares. “And it wasn’t just ‘another Hollywood marriage.’ It’s never as simple as that, when two people decide not to go on living together.”

And there wasn’t Someone Else, for either of them. It would have been easier to face, if there had been.

Kirk is busy. He has finished the part of the Gentleman Caller in “The Glass Menagerie,” having voluntarily stepped out of the fatter part, that of the brother, to make room for a man he worships as “sheer genius,” Arthur Kennedy.

With Kennedy, and a few other close friends, he had rich, satisfying relationships.

But of the hordes of other people who pursue him now, the beautiful women, the important men, he is a little afraid.

“Is it just because I’m a star?” he wonders. “Would they like me for myself?”

“I want to be admired, sure,” he says, “I want to be loved. Everyone wants to be loved. But there’s a hitch. I want to be loved, just, I guess, for myself.”

There was no “myself” in the dream. Only Somebody. And Somebody, once arrived, was not just Kirk. It was his father’s rebellion, Betty’s job at fourteen, the suitcase from Kay, the overcoat, the great country of his mother’s fulfillment. If all these made Somebody, then who, what, is Kirk Douglas?

Asking his questions, seeking his answers, Kirk Douglas is struggling to adjust himself to an unfamiliar reality.

It would be easier for him, probably, to go on dreaming, but no one can give back a dream which has come true.

“I’m not sure where I’m going now,” he says. “I’m not even sure who I am, Issur Danielovitch, the skinny kid, or Kirk Douglas, the star. But I know this much. You have to make peace with yourself as you are. Not just as you might have been, or are going to be.

“I’ll make my peace with reality, and then . . . then we’ll see.”

THE END

—BY PAULINE SWANSON

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1950

No Comments