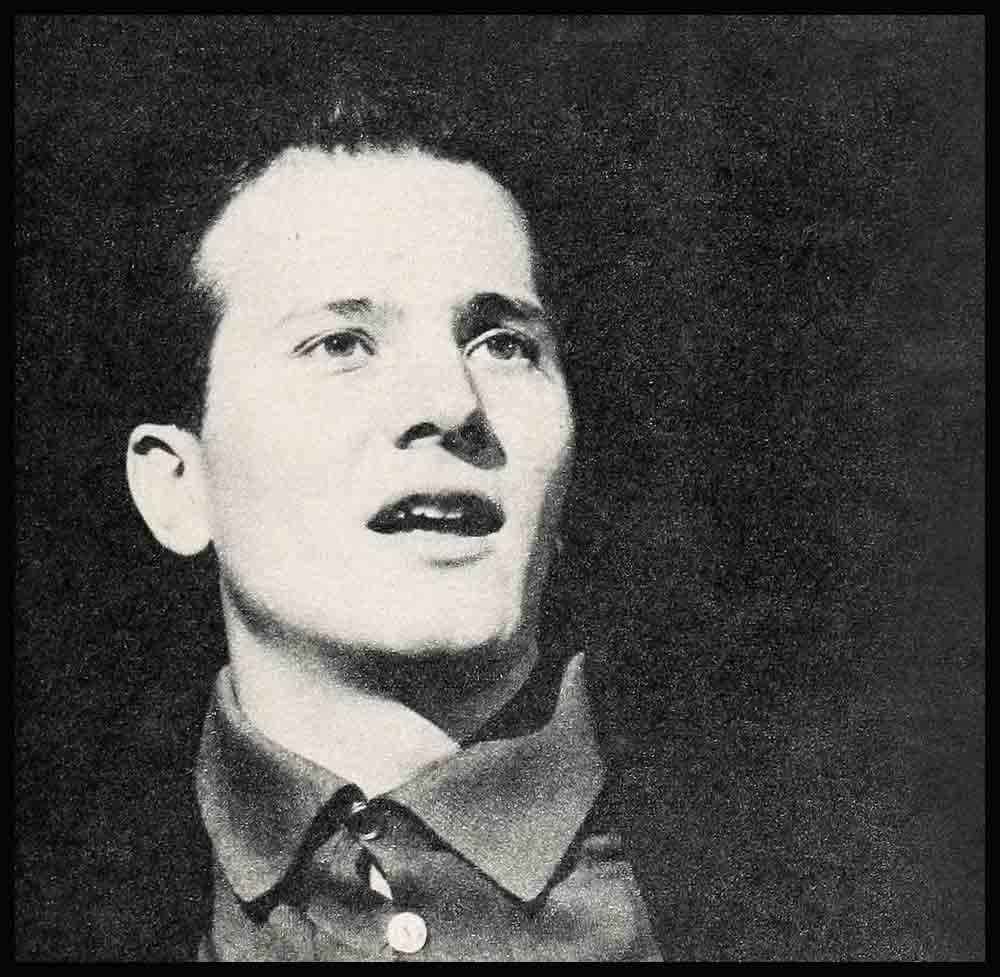

Let’s Draft Every Star Now!

Last night I got so mad I sat down and started to write a letter to President Kennedy. It began— “Dear Mr. President: I think every star should be drafted—and now! ” That’s as far as I got. I wasn’t writing about a government draft. I’m not trying to tell the President how to run his business. I meant a voluntary draft that could be run by the stars themselves! Yet, how could I put it into words? There was so much involved, so much that was highly personal. But first, I had to calm down and sort out my thoughts. I tore up the letter . . . picked up the newspaper story that had gotten me so steamed up in the first place. I reread the headline: “Star Arrested for Drunken Driving in Palm Springs.” The article told how a popular actor, who was vacationing in Palm Springs, had been arrested for drunken driving and disorderly conduct on the way home from a wild party. He’d fought arresting officers, tried to break a newspaper photographer’s camera, insulted the jailer and loudly claimed his rights were being violated.

It happens that I have great respect for that particular actor’s talent. And I’m not the only one. As a matter of fact, one of his fans recently asked m e if I knew him.

The fan was a young man in Sallsbury, Southern Rhodesia, a city in the heart of Africa—where every day men are being asked to decide between the forces of East and West. That young man’s decision, along with those of his fellow Africans, may eventually tip the balance of world power toward either communism or democracy . . . perhaps even toward war or peace.

What would that fan think, I wondered, if he could see this newspaper headline? Would he still be as fond of his idol?

Would he be as fond of America?

You know, I almost didn’t go to Sallsbury. It was to be one of the first stops on my recent personal appearance tour around the world, but at the last minute I was warned: “Stay away! There’s trouble!”

The danger was real. There’d been rioting in the streets of Sallsbury, martial law had been declared, and the British were sending in soldiers to keep the peace. The violence had been triggered by a referendum that was to be held in order to broaden the people’s voting rights.

I decided to ignore the warnings. My show had been advertised for several weeks and I didn’t want to let anyone down. But m admit I was a little scared as my plane circled the Sallsbury Airport. I’d been told that one of the factions in the constitutional battle might use my arrival as an excuse for staging a demonstration of some kind. And with an excited mob crowded onto an airport Ianding strip, any incident—a smashed sign, a shouted insult—could ignite a riot.

Plan to kidnap

There was another kind of incident that might cause trouble, too. I remembered what had happened at the airport in Johannesburg only a week before. Six young engineering students, wearing coveralls like those of an airline ground crew, had almost tricked me into taking a “ride” with them in a truck that turned out to be stolen. They claimed they just wanted to take my picture, but I learned later that they’d actually been planning to kidnap me and take me to their college outside Johannesburg as a “prank.” I’m sure they didn’t mean any real harm, but an innocent stunt like that could misfire if it were tried in the tense atmosphere of Sallsbury. The result could be confusion leading to accidental violence.

Although I was worried, I decided to wear casual vacation attire on my flight to Sallsbury. I stepped off the plane wearing a jaunty straw hat, candy-striped jacket and white slacks. But I kept a far from casual eye peeled for any unusual occurrences.

As the crowd saw me, they let out a roar so loud I stopped in my tracks. As the shouting subsided, I continued on down the Ianding ramp.

Just as I reached the ground, I heard a shrill scream a few feet away. I turned nervously to see what it was.

“Eeee! It’s really ’im!” a girl was shouting, and suddenly she thrust an autograph book toward me. With a sigh of relief, I scribbled my name and pushed my way forward through the crowd. stopping every few steps to sign another book.

So far, so good.

Suddenly a group of people wearing military-looking helmets and green overalls came through the crowd. I wondered—was this another prank, or worse yet, was it the start of some kind of “demonstration?” They looked like teenage boy s, but as they came closer I saw that there were girls’ faces under those helmets! Their leader came right up to me and began to shout, trying to make herself heard above the crowd. Finally I understood what she was saying.

“We’re the Vespa Scooter Girls!” she said. “We’re the honor guard that’s supposed to accompany you to your hotel!”

Right then I stopped worrying, and felt a little sheepish. I seemed to be more tense than the crowd was! Quickly my distrust melted. This wasn’t exactly like home, yet somehow the people seemed the same. I grinned, thanked the girl and walked through the rest of the crowd with my phalanx of “Scooter Girls” helping the police clear a path for me. At the terminal we all posed briefly on motor scooters—you should have seen me on mine!—then I got into a waiting car with my manager and the rest of our party, and the Scooter Girls escorted us to the hotel without incident.

From that point on I was too busy to worry about political riots or anything else. I held a press conference at the hotel that night and did a TV show. The next day I shopped, had a party for the local band and sang before 10,000 people at a local stadium. After that there was a children’s hospital to visit, and the day was over. I hadn’t seen any fighting—only friendship and courtesy everywhere.

That night I was packing in my hotel room when I heard a knock at the door. It was a bellboy with the morning papers, which featured stories of our visit on the front page.

“I thought there was supposed to be a lot of fighting and rioting here in Sallsbury,” I told him as I glanced at the papers.

“Yes, sir,” he said. “But that was before yesterday. . .

“What happened yesterday?”

Politics took a back seat

“Why, there was all the excitement over your arrival, sir. You see, everybody was so curious about seeing an American film star that the political side sort of took a back seat. I guess nobody had time to argue. Instead, we were all talking about your show on TV last night and the one today at the stadium.”

“You’re not kidding me?” I asked, hardly able to believe my ears.

“No, sir. You know, we love the cinema over here. And if it isn’t out of order, could you tell me if you know my favorite star—” And he mentioned the actor who got arrested in Palm Springs. I told him I didn’t know him personally, but agreed that he was a very fine actor.

“I’m glad you think so, sir,” he said. “And may I say it was a pleasure talking to you? You know, I . . . well, frankly, I’ve always wondered if you Americans really cared about us over here, or even knew about our country. That’s why I was so glad to see a performer like yourself taking the time to come visit us. I hope many more come over, and . . . who knows . . . maybe I’ll get to America someday. . .

“I hope you do, I said. And thank you.”

After the bellboy had left and I’d resumed packing, I felt very elated—but depressed. I was glad our visit had taken people’s minds off their hatreds, yet I was unhappy because I knew the fighting would probably resume the next day, after we were gone. I knew it was no special tribute to me that the tensions in the city had relaxed; it would have happened if the performer had been Bob Hope, Danny Kaye, Debbie Reynolds or any American star whose records and pictures were known in Africa.

I also realized that although Bob, Danny, Debbie and several other stars, including Paul Anka, Connie Francis and Johnny Mathis do travel around the world entertaining and making friends for America, too many others prefer to stay among the comforts of New York, Hollywood. Las Vegas and Palm Springs. They just let their movies and records work for them and bring in the money.

That’s all very well, and entertainers are entitled to comfort and rest just like anybody else. But can a movie create the kind of excitement that makes people forget to fight for a day or so? Can a record sign autographs, shake hands, let people know that Americans care? You know, a performer is lucky. If the public accepts him, he can not only become rich and famous beyond his wildest dreams, but he also gets a ticket to people’s hearts. That ticket is good wherever his name is known. A performer has to use that ticket—and it doesn’t do him or anyone else much good in Palm Springs.

I’ll admit there are times, though, when an entertainer isn’t too happy to see his fans. I felt that way myself at 6:30 one morning in Durban, South Africa.

Somehow I’d forgotten to lock the door of my hotel suite the night before. Even before I opened my eyes that morning, I sensed there were people staring at me. At the same time, I remembered I didn’t have a stitch of clothes on under the covers! I was so sleepy, I just lay there in a daze.

Finally I managed to open one eye— and then the other flew open, as I saw ten teenage girls and three small boys standing around my bed staring at me.

“Hey, what is this??!” I asked as I sat up, pulling the covers up around me with what dignity I could muster.

“We just wanted your autograph, Pat,” one of the girls said. And she held her book out for me to sign.

Now, if there’s anything I hate, it’s being awakened early. And the 6:30 I saw on the face of my travel alarm was a good hour before my usual reveille.

“I’ll sign later,” I said, trying to keep my patience. “I’ve got to get dressed now, if you’ll . . . just . . . leave. . . .”

“Please! Couldn’t we have it now?” the girl insisted. “After all, we’ve been waiting a long time for you to get up, and there wasn’t much to do in here except stand around and hope you’d hurry!”

At that point one of the small boys edged away and stepped out the door.

“I was trapped!”

“All right,” I said, and they all came around to the side of my bed and stood in line while I signed each book. But before I’d, the boy who’d left the room returned—leading several other kids.

“See? I told you!” he smiled triumphantly. “It’s Pat Boone in person, signing autographs!” Shrieking, the other kids held out books for me to sign. What could I do? I was trapped!

As I sat there signing away, I noticed one of the girls was opening all the closet doors and peering inside.

“Hey! What are you doing?” I asked.

“Looking for those red corduroy pants,” she said matter-of-factly. “I think they’re smashing! I mean, the ones you wear when you’re alone in your room.”

“How did you know about those?!” I asked.

“Easy!” she replied. “See that building over there?” And she pointed out the window. “That’s the hotel where I’m staying. I have a perfect view of your room, and I can see you walking around in those red pants. I want you to put them on so the other kids can see them.”

“Remind me to close the curtains next I time,” I said with a groan. “Now look, kids. You’ve just got to get out of here so I can get some more sleep!”

They did—half an hour later, after I’d signed all their books. Then, holding my blanket around me, I made a dash for the door, locked it, pulled down the shade— and fell back into bed exhausted.

Embarrassing? Sure. And yet that little bedroom farce taught me that kids are the same the world over. They can be wonderfully annoying, and annoyingly wonderful. And it’s when they’re annoying that they need you most. They all respond to friendship and patience. Maybe I wasn’t in an ambassadorial mood that particular morning, but at least I didn’t blow up. And I think the net result was a closer friendship toward Americans on the part of those youngsters. What’s more, I’m sure they told their friends about it.

Funny … I went all the way around the world on that singing trip of mine, and yet I keep telling you about what happened in Africa. I guess it’s because I think Africa is typical of the areas whose friendship we’ll need if we’re to hold our own in the struggle between liberty and slavery, peace and war. Also, many of the lessons that I learned in Africa were reinforced as I continued my travels.

But one lesson, one experience, was unique. This, too, happened in Durban, South Africa, but it wasn’t funny. Not at all. It took place during my first stage show there. and İTİ never forget it as long as I live. It was a powerful example of what one person can do to help the cause of brotherhood and understanding if he tries—and cares.

In South Africa, as you may know, there is a policy of apartheid—strict segregation of the races. In Johannesburg, it’s still against the law for performers to play before audiences that include both Negro and white people. And in Durban, no white performer had appeared before a mixed audience in years. Well, I had come to sing for people—anybody who wanted to buy a ticket. Through the cooperation of the theater manager and others, tickets for the same performances were sold to people of any race. There was no publicity in the papers about this—we just went ahead and did it.

On the first night of the show I stood anxiously in the wings of the Icedrome. Had we made a mistake in daring, as outsiders, to break down the barriers between races? The evening would tell the story.

The manager of the Icedrome came up to me and said, “It’s a terrific crowd, Pat. Over 5,000 people are waiting for you out there!”

Waiting for me. But were any of them harboring a secret grudge? Would there he any racial agitators in the audience?

I peeked at the crowd through a hole in the curtain. There they were, Negroes, Indians and whites alike. True, they were in separate sections—but the fact that they were in the same theater at the same time was unique for Durban. I hoped everything would go well.

The opening acts went on to tremendous applause, and we were all encouraged. Then, after the intermission, it was my turn. I heard someone say, “You’re on!” and I stepped into the spotlight. There it was again—the applause. I’d never been so glad to hear it, never been so grateful.

Somehow words seemed inappropriate—so I went right into “April Love,” a song from one of my movies. At the end of the number, the applause came across the footlights, full and strong. But by the time the evening was over, I realized that the audience deserved the true applause. They deserved it for adjusting beautifully to a situation that must have seemed strange to many of them.

As I left the Icedrome that night, in a strange city and a strange country, I couldn’t help wondering—if one entertainer can help bring different races together in Durban, couldn’t hundreds of entertainers fanning out over the world help bring countries together?

When my trip was finished and I was home in Beverly Hills with my family, the temptation was to forget about the rest of the world, to forget about what I’d seen and concentrate on my work. But I couldn’t forget. I knew that as long as the Russians were testing atom bombs in Siberia, as long as Russian dancers and singers were touring the world in a highly successful effort to win friends for their way of life through their talent, I couldn’t forget—for my own safety, for my family’s safety, for the world’s safety.

That’s when I decided that if I couldn’t do anything about the Russians’ bombs, at least as an entertainer I could fight talent with talent. But I couldn’t do it alone. Only a whole group of performers working for a single cause could do it.

After I’d torn up my first letter to the President, I sat for a long while at the desk in my den, trying to figure out exactly what entertainers like myself might do to help fight Communism around the world—and above all, to help prevent war.

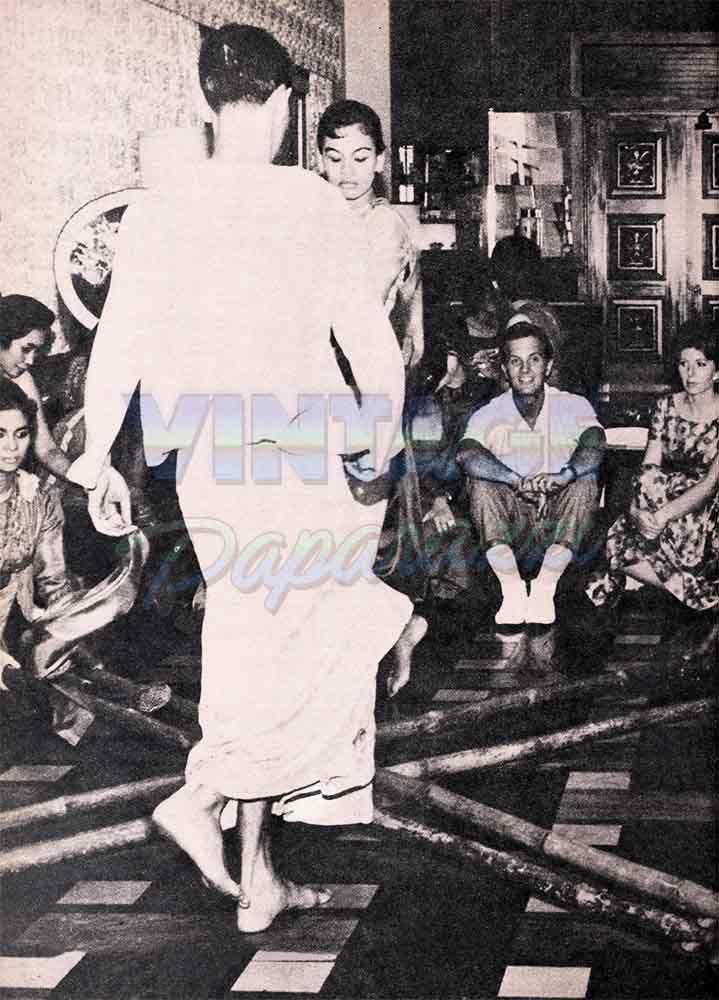

The first thing I realized was that others had already done much in the right direction. Danny Kaye, with his travels for the United Nations children’s organization, has worked wonders in fostering world understanding and promoting good will toward our country. And when I was in Manila during my tour, everyone was talking about the terrific show Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Shirley MacLaine and other stars had put on to celebrate Philippine Independence Day. Nearly 20,000 people sat and stood (the stadium seated only 5,000) in a downpour to watch the many American stars who had come so far to show them that America cared.

We need more of this. And I think I know how it can be done, on a scale as yet untried. I’m working on a new letter to the President, setting forth this plan:

Let every entertainer volunteer his Services to the government once a year, for a period of a week to a month. During that period he’d travel wherever the government wanted him to go, doing whatever his specialty might he—singing, dancing, telling jokes, acting in dramatic sketches. And, above all, meeting the people. If he couldn’t perform on a stage, then he could give interviews to the local press, tour children’s hospitals, visit schools— anything that would help promote friendship and understanding between other nations and our own. He wouldn’t have to keep saying, “I’m an American”—everyone would know that. And if he made a hit with the people of other countries, he’d be helping to make our nation popular. After all, here in this country we don’t forget that Maurice Chevalier is French, that Sophia Loren is Italian, that Cantinflas is from Mexico. And when we admire their art, we admire their country just a bit more, too. That’s what I want American entertainers to achieve for America.

Entertainers For Peace

All these activities would be coordinated by a special organization that would be set up by the government. Call it Entertainers For Peace, for example.

Would the stars be paid? That would depend on their situation. In fact, if they wanted to combine their own professional activities with their government service, that would be all right, too. For instance, if there had been such an organization during my trip, I could easily have combined good will appearances for the government with my own performance schedule. In fact, the performances themselves would have tied in with the whole plan perfectly. On the other hand, if a star wouldn’t ordinarily be going abroad, he might team up with several others into a troupe, with their expenses paid either by the stars themselves or by the government. Individual theatrical companies have already traveled this way, but never as a part of an organized effort extending through all of U.S. show business.

Actually payment details could be easily worked out if everyone got behind the plan. And in a very real sense, every star would be paid, whether or not he received actual money for his services. He’d be paid by having his audience enlarged from millions to hundreds of millions. He’d be paid in unforgettable experiences that would enrich his art and stimulate his talent. He’d be paid in new understanding that would make him grow as a person. Above all, he’d be paid in the satisfaction of helping his country at a time when no effort for peace should be left untried, no chance to help America ignored.

Entertainers For Peace. I like that name. Maybe that should be it. In any case, I’m leaving it up to the President, and I sincerely hope he’ll see fit to act on my suggestion. If he does—well, you’ll be reading about it.

And if he doesn’t, who knows? Maybe an even better idea to help America will come from you.

THE END

Pat’s next film is 20th’s “State Fair.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1962