The Rebel And The Lady

Whether they like it or not, they’re going to talk about it. Whether they like Carroll Baker or not, they’re going to talk about her. “Baby Doll” is that kind of picture. Carroll Baker is that kind of girl.

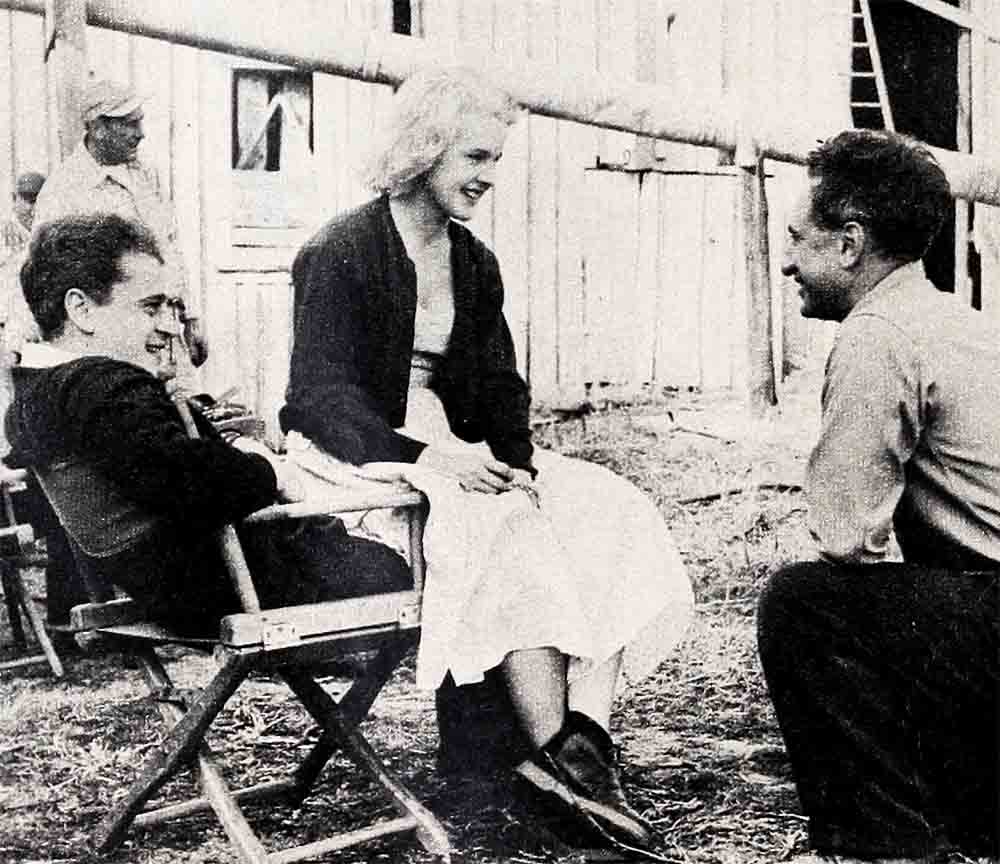

Doing her second movie role in a picture that is admittedly going to stir up controversy, a picture that is all hers—-with Elia Kazan directing her, and Karl Malden and Eli Wallach working with her—sets Miss Baker right out in front of the female contingent of “the rebels,” “the blue-jean set,” “the Actors’ Studio crowd.” Elia, Karl and Eli are three of the most forceful of Hollywood’s forceful new generation. “Baby Doll” is one of that generation’s most exciting creations. It all adds up to make Carroll a sure bet for notoriety, if not fame.

AUDIO BOOK

The question is sure to arise, is she really a blue-jean kind of girl? Is she a feminine version of the leather-jacket, motorcycle-riding boys who have set staid Hollywood on its ear in recent years? Or is she just an actress doing a job? In brief, is she a rebel or a lady? Or is it possible that she’s both?

On the face of it, Carroll is certainly a product of the famed Actors’ Studio in New York. Lee Strasberg, head of the school, gave her private lessons. She was taken straight from those and a few roles on TV and Broadway to “Giant.” She was chosen by George Stevens, as shrewd a judge of talent as there is in Hollywood, to play Elizabeth Taylor’s younger daughter, starting at the age of eleven and progressing through her teens to the point of having a one-sided romance with Jett Rink, played by Jimmy Dean. Stevens, after watching her work, said that she is one of the screen’s great finds. Kazan, choosing her for the taxing, powerful role of Baby Doll, said the same.

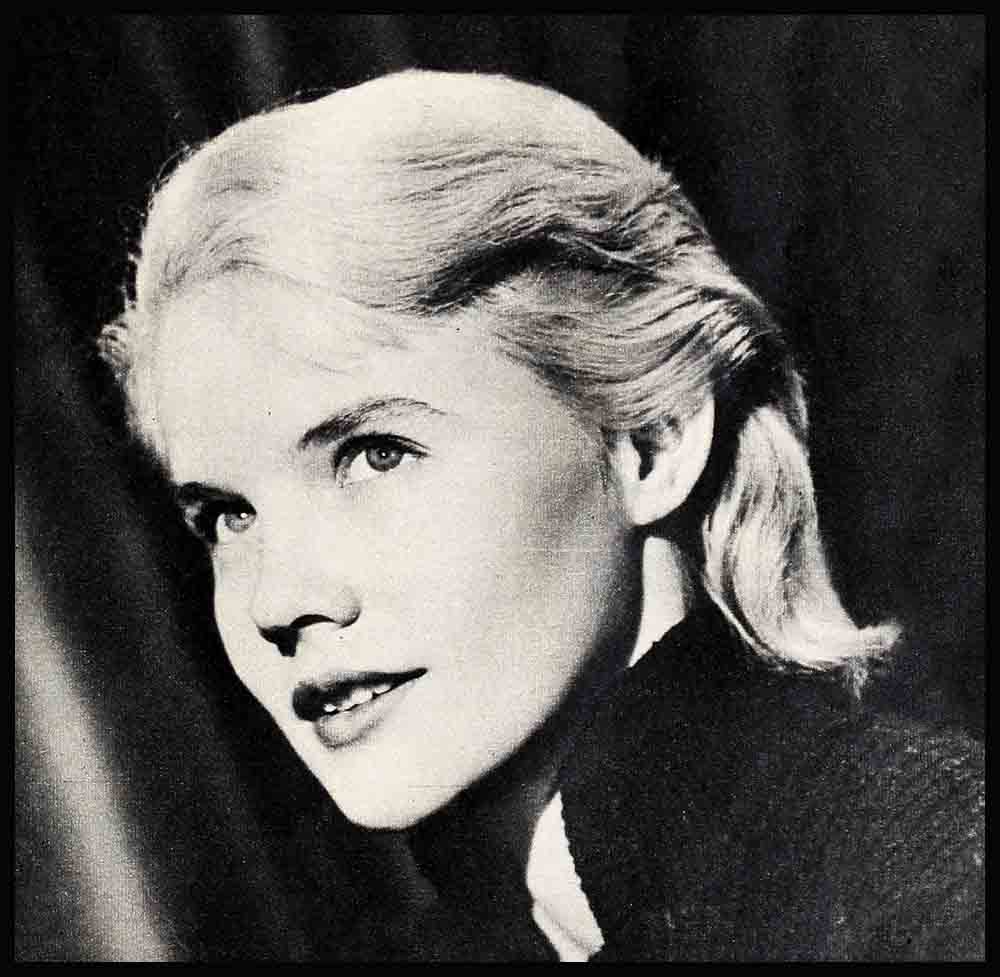

In appearance, Carroll has a round-faced prettiness which she deplores. Sometimes she stands in front of a mirror and sucks in her cheeks, hoping it gives her the gaunt, Katharine Hepburn kind of attraction she’d like to have. And she showed up for our interview at one of New York’s fashionable theatrical restaurants—having traveled by subway—wearing a tweed skirt and topcoat. no hat, with scarcely any make-up. As she entered, no heads turned.

Carroll has other facets that link her to the volatile, tension-ridden “rebels” who have invaded Hollywood. In one of the first interviews she ever gave she admitted that, like some of the others of the group, she was no stranger to psychiatry. However, she also said that she does not think of herself as a rebel.

“If we are a bunch of rebels,” Carroll told me during our lunch, “what we rebel against is not so much the established pattern of living or acting, but, rather, the temptation to let ourselves be made into something we aren’t.”

Then what are they, these so-called “rebels”? Certainly not glorified juvenile delinquents, although Carroll, you would say, might have been: child of a broken marriage, brought up in a small factory town in Pennsylvania by a mother who had to scrimp and toil to keep her family together. And Carroll began dancing professionally in Florida night clubs in her early teens. But none of that explains the special quality of her personality—and of her acting—which makes her one with the “rebels.”

On the contrary, out of that rugged childhood has come a typical quiet, pretty girl with good manners, a happy young wife and mother, one who lets her talent make its own rules, rather than being driven by a rabid thirst for publicity, glamour or money. She has the beauty for such a pursuit, as could be seen even with the tweed skirt and the wind-ruffled hair. Her dark blue eyes, beautifully set, are surrounded by skin of the clearest alabaster. “I’ve never had much trouble with it, thank goodness,” she said. Her light tan hair was dyed more blonde for “Baby Doll.” She’s short, a mere five-feet five, weighing 113 pounds, but even that would not keep her from throwing her weight around as a glamour puss, if that was the way she was inclined.

But she is not so inclined. She’s too much a lady to make such use of her looks, too much of a rebel to dissipate her heaven-sent talent in any unworthy way. Lady and rebel, she is just a lucky girl who was gifted with inborn talent, an honest girl who followed the dictates of that talent on a swift ride to fulfillment.

The swiftness of Carroll Baker’s rise, the briefness of her apprenticeship for the demanding Baby Doll role, is also a part of the “rebel” legend. After the Florida night clubs she went to New York in 1952, did a certain amount of television work, took lessons with Strasberg and made her Broadway debut in “Escapade.” Then she won the role of Ruth in Robert Anderson’s “all Summer Long,” and was hailed by the critics as “outstanding”—an accolade not to be underestimated. Then “Giant.” In private life, Miss Baker is the wife of twenty-six-year-old stage and screen director Jack Garfein. They were married on April 3, 1955. When we had our luncheon conversation in New York, she was carrying their first child.

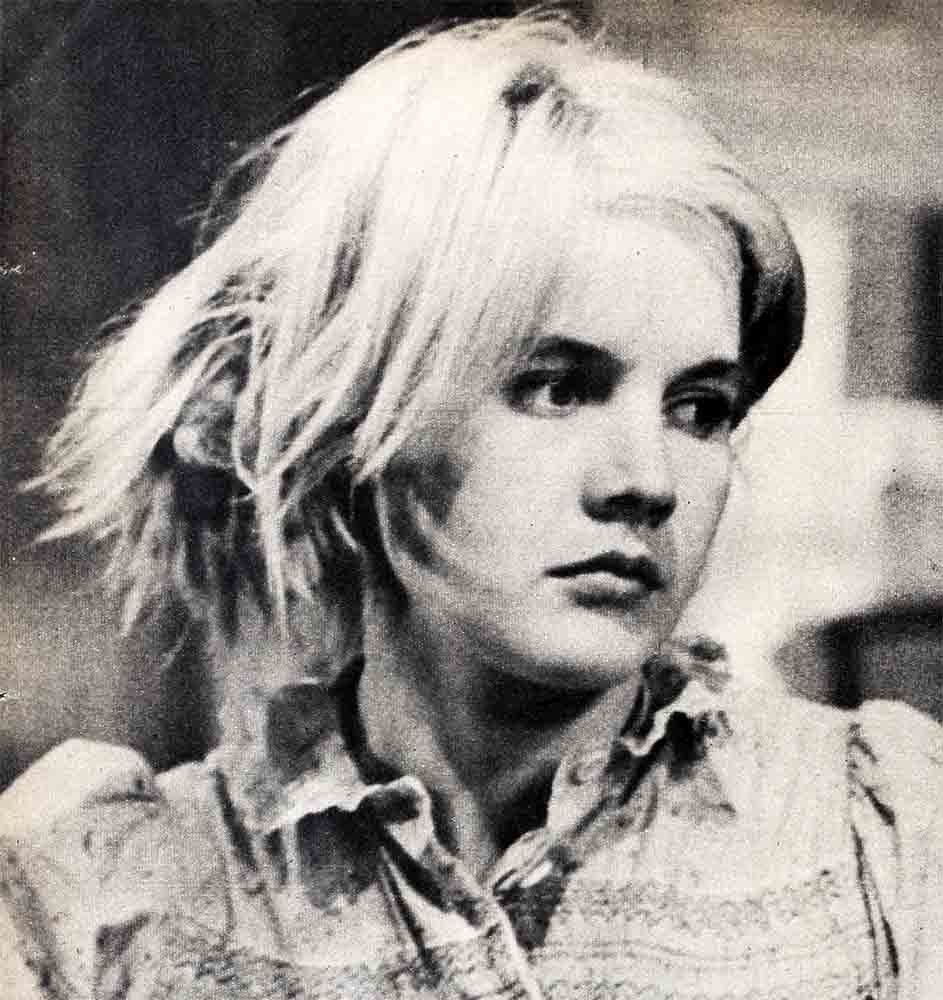

Dedication to her work is another part of the legend. Two weeks before the rest of the “Baby Doll” cast, Carroll arrived on location in Benoit, Mississippi. She was there for the single purpose of getting to know the place, drinking in its character and color, talking to the townsfolk and acquiring an accent like that of her temporary neighbors. It is an approach to a role which Elia Kazan invariably recommends; but it was Carroll’s talent for observation and mimicry that caused the rest of the crew to find, on their arrival, the authentic Baby Doll waiting.

“I’m a compulsive mimic,” she says. “I act and look and even feel different every day, according to a play or movie I’ve seen, or some person who impressed me. Meet someone with a strange speech pattern—and I immediately take it up. Copycat a character for a stage or screen role—and I’m stuck with her mannerisms for weeks. After ‘Baby Doll,’ for instance, I had my thumb in my mouth so much, biting my nails, fingering my lips—things I’d never done before—that my husband Jack said, ‘Look, when are you going to come out of the woodshed?’ ”

And is being “different” a part of the legend? The word has often been used to set “the blue-jean crowd” apart from often equally talented, equally dedicated. equally personable contemporaries. If they are indeed different, what in their lives, or within themselves, makes them so?

“I can’t speak for the others,” Carroll Baker said when I put the question to her. “But, speaking for myself, if I am different from hundreds and hundreds of kids who come from small towns and modest homes, have a dream, and work hard to make it come true, with, along the way, the usual quota of adventures and misadventures, I can’t think how.”

She was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, the daughter of a traveling salesman named William Baker who later became a farmer. This took the family to a tiny community outside the steel town of Greensburg, where Carroll and her sister went to high school. The sister, Virginia, is now eighteen and married to a boy in the Air Force. They live in Florida.

While the girls were still quite small, their parents were divorced. All the same, Carroll remembers her childhood as having many happy moments. Most of them rose from her passion for pretending, acting out things, singing and dancing. While her lonely yet cheerful mother bent over a washboard—a picture Carroll carries with her indelibly—the two played a game of pretend, with Carroll as the tiny leading lady, her mother and sometimes her sister in supporting roles. They had a regular repertoire of scenes, which Carroll wanted to play over and over. “Then my mother would say, ‘Leave me alone. I have to get back to work,’ ” says Carroll, with a sigh of regret even now. “And I’d have to go back to being just me.”

When she was eleven Carroll began taking dancing lessons. “What I really wanted to be,” she says, “and still wish, more than anything, that I could have been, is a ballerina. But I didn’t start soon enough.” Her other ambition, which grew on her more gradually, was to be a serious actress. Like Garbo in “Camille,” a picture that she hastens to see every time she hears of it playing somewhere. She tried out for the school plays, but was never given an acting part. Instead, she danced in all the school operettas. After she graduated from high school she went to Florida with her mother. There she enrolled in St. Petersburg Junior College, but, already a professional dancer, she had to leave after her first semester. “So many dancing jobs came along that I couldn’t study,” she says. “And heaven knows we couldn’t afford to turn them down.”

The pattern changed when she decided to go to New York and try her luck in the Big Scramble. Her first jobs were on TV, and not dancing ones. She did such things as commercials, small parts in plays, and for a time even a nightly weather report over a local channel. “One dreadful night,” she recalls with an expressive shudder, “I lost my cue card for a report. I was panicky, and said the first thing that came into my head. It turned out to be: ‘There’s a lot of hot air blowing in from Texas.’ That ended the brief career of Carroll Baker, Girl Weather Analyst!”

It was after appearing in several TV dramas that Carroll’s interest in becoming a “serious” actress came to full bloom. She discovered that the Mecca of all the “serious” acting ambitions in New York was the Actors’ Studio.

“On what turned out to be the most important day of my whole life,” she relates, “I arrived at the Studio. I had no idea, of course, that the audition I hoped to get would come from my future husband, who was on the Board. But when I opened the door there he was, behind the desk, subbing for the secretary who was out to lunch. I thought him a very odd boy. Red, sort of bushy hair, workman’s shirt, gray, collar open, no tie.”

But when Jack Garfein told her his name she knew who he was. She’d heard about him as a very promising young director who had been instrumental in giving a lot of young players their start. Taking heart, Carroll asked him how she should go about getting an audition at the Studio. There are two auditions, Jack explained, the first before a board made up of the students; the second (“assuming you pass the first”) before the Board of Directors. At the moment, he added, the roster of the school was filled up. But, he went on quickly, she ought to prepare a scene for auditioning and keep on coming back. “Be Johnny-on-the-spot,” he told her.

“I kept on coming back,” she says. “Each time I did, I saw Jack. Each time I saw him, I was glad. Meanwhile, I’d prepared a scene from an old Paramount picture, ‘Sullivan’s Travels.’ Kind of a depressing little scene, two kids, boy and a girl, no money, dreary. . . .”

Jack wasn’t present on the board the night she finally made her audition, but he saw a rehearsal of her scene in the studio she had rented for the purpose. He was an hour late getting there. “I had to rent the studio for another hour!” she says, still pained at the waste. His comment was: “You’re so wrong for the part, it’s amazing you do it so well.

“I have a feeling,” was Jack Garfein’s verdict, “that they won’t pass you. But they may ask you to come back.” They didn’t do either. Not until after “Giant,” in fact, did Carroll pass her auditions and become a regular member of the Studio. But Lee Strasberg accepted her for one of his private classes.

The day I went to my first class, Jack called and asked me for a date,” Carroll says. On that first date they went—by subway—to visit friends in Greenwich Village. Theatrical people, of course, a set designer and his wife. After that, the dates went on. Sometimes Carroll would fix dinner for them in her tiny apartment, the menu generally consisting of noodles stuffed with cheese. For amusement they went for long walks. (“We still do.”) They read plays together. Sometimes people gave them theatre tickets. On other evenings they visited a pianist friend and listened to her play. Wherever they went, they used the subway.

“When we did have some money—after all, we both did work once in a while—we’d have dinner at our favorite Chinese restaurant,” Carroll relates. When they were really in the chips they went to the Russian Tea Room, an artistic hangout near Carnegie Hall, where Jack could indulge his passion for the shashlik.

On one occasion when finances were at a low ebb, Carroll was offered a wonderful job: a cigarette commercial. “Only I don’t smoke!” she wails. She needed the work so badly, however, that she decided to bluff her way. At the first interview they liked her looks, young, “sort of normal,” as she puts it. “They said I ‘went well’ with the boy they had in mind for me to work with. Then they asked, ‘When you smoke, do you inhale deeply?’ ‘Oh, of course I do!’ I said fervently.”

They gave her a carton of cigarettes and she went home and smoked and smoked, coughing all the while, and succeeded in making herself deathly sick. At the second interview, they liked the way she read the lines. Then came the moment she had to inhale.

“I took a tremendous draw, and didn’t cough at all. But tears came to my eyes, spilled over, splashed. The atmosphere chilled. They still liked me very much, they said,but . . .” Nevertheless they gave her more cigarettes to take home. Again she smoked and coughed herself sick. At the final audition, though, she inhaled perfectly, and the job was hers. A commercial, of course, has to be perfect; movements, expression, everything, has to be just right. Filming the tiny sequence went on for nine hours, shooting it over and over again. When Carroll reached home she was so horribly sick she wanted to die. And the next week, the check she received came to just half of what she had expected.

“But it turned out that for six months you’re paid fifty dollars every time they show the commercial. That was marvelous. For the next six months Jack and I ate regularly at all the nicest restaurants!”

The two youngsters were most prosperous during the Broadway runs of “Escapade” and “All Summer Long.” But plays run just so long, and it was just as their money ran out once more that they decided they wanted to get married. Since this was to be for keeps, they wanted to do it nicely, but how, with no money? Then Lee Strasberg invited them to have the wedding in his midtown apartment.

“I decided to make my own wedding gown,” Carroll says. “I bought yards and yards of off-white silk crepe and a pattern. Then I rented a portable sewing machine and went to work. It was a very intricate pattern. Long, tight sleeves, a formfitting tucked bodice and a bustle for underneath. A long, long skirt which Jack hemmed up for me. That turned out to be a little crooked, but the skirt was so long it didn’t matter. For the headdress I used net with seed pearls sewn on it, one by one. At five o’clock on the morning of the wedding I was still working on my dress. At seven o’clock I rushed over to the Strasbergs to press it. While the guests were arriving, I was out in the kitchen ironing!

“Then the rabbi arrived and it was a beautiful wedding, with champagne, flowers, cake and Susan Strasberg dressed in lavender. She was my maid-of-honor, carrying a small, sweet bunch of violets, and I carried white camellias to match my beautiful wedding dress. A Baker Original!”

Three weeks after the wedding, Carroll received the script of “Giant.” When she reached Hollywood, she borrowed on her salary so that Jack could come out, too. It was wonderful for him to watch George Stevens at work and, later, Elia Kazan. While Carroll was in Mississippi Jack was with her there, too. “Cheaper for him to fly down than for me to call him every day!”

Then, last summer, Jack got his big break when he directed “End As a Man,” starring Julie Wilson and Ben Gazzara, for Columbia. He’s preparing now to direct “The Girls of Summer,” a new play starring Shelley Winters, which will open on Broadway. The young couple have taken a new apartment in New York. “I could write a sonnet to the dishwasher!” says Carroll.

Are the members of “the blue-jean set” different, then? “I don’t think that we are different within ourselves,” says Carroll. “I just think our values are different. We’re not impressed, that is, by the big car, big house, swimming pool, bosomy blue mink glamour routine. Most of us laugh at it. We want to live nicely but we have a sharp eye out for the future. We save our money.

“Because Jack and I don’t go out much, don’t smoke, don’t drink (we like a little wine), and spend most of our time at home, we put out more on rent than we might otherwise do. Also a lot on books (old cookbooks are my hobby) and records. But we sort of arrange our budget so that if there is an extravagance, it’s balanced by an economy. In our bedroom we have a huge bed and nothing else but that! For our all-white living-room with its salt-and-pepper cotton carpeting we found a drapery material we were crazy for. Then we found out that the cost, including the making, would be $700, so we said, ‘We’ll wait a few months.’ When the painters made a mistake and painted Jack’s study pink and the baby’s room cream and would only do one of them over for us, for free, we had only Jack’s study done over. The baby will just have to get along as is!”

Carroll thinks the motives of her group may be a little different. Their drive is toward finding themselves as actors, being in good things, working with good directors. Their concern is focussed on bringing alive the characters they portray so that people will forget the player in watching the play.

“Sometimes I think we are a little too relaxed, go overboard a little about the way we dress,” Miss Baker admits. “Uhhuh, the blue jeans. Actually, though, the jeans were an economy measure, a sort of occupational necessity, rather than sloppiness or a wish to be ‘characters.’ Now that the Actors’ Studio has moved to a better building, the blue-jean trend is changing. Not that I, for one, will ever go to the other extreme. I’m afraid I don’t care for the glamour things. Don’t care for furs. Just kills me to put out money for jewelry. Not crazy about perfume. Except for sweaters and skirts and tweeds and good leather purses and shoes, which I love, I’m not very clothes conscious. But I do take time to put on a dress, try to look nice, when I go out. I don’t want to be conspicuous either way.

“I don’t suppose that Jack and I will always live as simply as we do now, in a lovely but relatively small and inexpensive apartment. As your family increases, your demands increase. When there is a baby, there has to be someone to watch him. As your career grows, and you play star parts, you’re too tired to come home and cook. But when you do have a bigger home and more help, you have them not for display but because they’re necessary. As, for a time,” said Miss Baker, with a lift of the eyebrow, “the wearing of the blue jeans was!

“What it all comes down to is this. Our difference, if there is a difference, is that we want to live our lives in our own way, not in the way, whatever it may be, movie stars are supposed to live.”

So speaks a lady. And, in her own sensible, balanced way, a rebel. Most of all, a superb actress destined to bring all of us many hours of pleasure.

THE END

Plan to see: Carroll Baker in ‘‘Baby Doll.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK