He Knows What He Wants—Mario Lanza

Rex Cole, one of the few really conscientious business managers in Hollywood, shuffled into Mario Lanza’s home in Bel-Air a few nights ago, his face crossed with lines of worry and care.

Ever since Mario broke irrevocably from Sam Weiler, his first personal manager who took from 10% to 20% of the tenor’s tremendous earnings in addition to working as the producer on Lanza’s radio show, Rex Cole has been trying to bring some order out of Lanza’s financial chaos.

On this particular night he had come to discuss Mario’s astronomical telephone bills. However, Mario was rehearsing—he practises anywhere from four to ten hours a day—and Rex Cole knew better than to interrupt.

Rex looked around, and he spied Mario’s wife, Betty. She caught the worry in his eyes, rose, and tip-toed from the room.

“I’m sorry to disturb you, Betty,” Rex began, “but these telephone bills puzzle me, especially the long distance tolls. They run into thousands of dollars.”

Betty smiled, and her flashing brown eyes turned soft. “I know,” she said. And then with a friendly shoulder pat “It’s all right, Rex. It’s for the sick.”

Rex Cole shook his head in puzzlement. “I’m sorry, Betty. I don’t get it.”

“It’s very simple,” Betty Lanza explained. “Mario sings over the telephone to sick people. If a man writes him, say from Omaha, and tells him that he’s going into the hospital for an operation, and he’d love to hear his voice again, Mario can’t help himself. He serenades the guy via long distance.

“Not only that. You’ve seen some of the doctors’ bills? Lots of times Mario insists upon flying a specialist to the patient’s bedside. Only a few days ago he had a cardiac specialist, a friend of his in New York, examine one of his fans.”

Rex Cole has been a business manager in Hollywood for 27 years—he’s handled practically every big name you can think of; he’s accustomed to the unique and the unusual—but this time he was really flabbergasted.

“I know about that Raphaela Fasana girl from New Jersey,” he said, “but do you mean to tell me that Mario does this sort of thing regularly?”

Betty nodded. “The more you’re around him,” she said proudly, “the more you’ll see that his heart is as big as his voice.”

“All I can say,” Cole muttered, “is that the public really doesn’t know Mario Lanza.”

What Cole meant was that a tremendous hiatus exists between the Lanza that really is and the Lanza people read about.

Here is a man who was not only unemployed, but deprived from making a living from August 1952 to April 1953. He was not only suspended by his studio but prevented from appearing on the CocaCola radio show thus causing the cancellation of the program. In addition he was sued for more than $5,000,000 and simultaneously informed by the crack accounting firm of Haskins & Sells that despite having paid the Government $485,000 in taxes, he was still behind in his payments. Moreover, he was informed that his financial records, whose upkeep he had entrusted to others, were so incredibly confused that it would take months of detailed auditing to determine just how deeply in the red he really was.

With this sort of financial ruin hanging over his head, with the realization that he had sung his heart out for ten years and money-wise had nothing to show for it, Lanza still insisted upon answering each and every fan letter, still insisted upon using the long distance phone to encourage those who were ill or hurt, and to sing for anyone he might help with his voice.

No matter what the cost, he refused to break faith with a public that had given him its confidence.

Lanza, who is much more profound and philosophical than most people think—he is an omnivorous reader of catholic taste—once tried to explain how he felt about his talent and the public.

“The voice I have,” he pointed out, “it’s difficult for me to express myself about it exactly. I feel it belongs to the public, that it was given to me to entertain people, to make life a little brighter for them.

“That’s why I never abuse it. People who tell you I do—they just don’t know. When I was a kid in New York I quit the Celanese Hour because I knew the voice needed further training.

“I don’t want to sound pretentious, but the voice is kind of like a sacred trust to me. If I don’t use it wisely then I feel I’m cheating the public, and that’s one thing I’ll never do. They can sue me for fifty million dollars, a hundred million. I’ll declare bankruptcy before I compromise the voice.”

This is the man who six months ago was pilloried and described as “an un—grateful ham, a real madman.” The barrage of insult has thinned down, but as a result of it, many people are still convinced that Lanza is an unstable character of little-boy moods, a sybarite who indulges himself in Farouk-like pleasures, or a bellowing bull who sweeps everything before him.

Actually he is a kind, hyper-sensitive, super-generous artist with a great love of people and an abiding sense of humility.

He may stalk his living room, shouting at one of the help, “I’m a tiger, Johnny. Don’t mess around with the tiger!” But these exclamations are manifestations of his sense of humor.

Johnny Mobley, the cook who works for the Lanzas, says, “You can judge a man by the way he treats his help. I can tell you Mr. Lanza treats us all fine. Everytime I bake some cookies, he says, “The best, Johnny. The best.’ I never serve him but what he’s extremely grateful. And he treats everyone the same, makes no difference, white or colored, big star or newspaper boy. He loves people, and he loves to sing for ’em. I’m tellin’ you. He’s as nice a man as I’ve ever worked for. Fact of the matter is he’s so nice you think maybe he comes from my home state of Arkansas.”

Pages could be filled with similar glowing quotations; but they would all point up the same two facts: Mario Lanza is kind, and Mario Lanza is so trusting that he’s frequently taken to the cleaners by the very ones he’s been kindest to.

Here’s an example. A few years ago, Mario was approached by a man who’d just been fired from MGM. The fellow was on in years, he’d seen a lot, and Mario without any fuss, put him on the payroll as a general assistant. A few months later, this same individual turned up at the studio and offered his services as a spy in the Lanza household.

Mario was told about this but he refused to believe it. Month after month he carried the guy on the payroll. Finally when it was no longer financially possible, he let the man go. You should have heard the vituperation, the slander, the insults.

This case can be multiplied half a dozen times, and the wonder of it all is that Lanza still retains his basic faith in the essential goodness of people.

However he has learned one lesson. Now before he hires new personnel, he is doing a bit of preliminary investigating. He’s kissed off his former press agent, his old business manager, his old lawyer and surrounded himself with men of proven competence.

It is no secret that Lanza refused to continue with The Student Prince last August because he could not see eye to eye with the studio on the way the production. was being handled.

Mario felt that his fans as well as himself were entitled to the best not only in music but in musically experienced directorial personnel.

He just did not want to go through all the agony he had experienced in Because You’re Mine, a picture he did not want to make.

People told him that he was being difficult, that he should “stop making it a Federal case,” that he should “walk through” The Student Prince and not take it too seriously.

“What do you care about the director or even the assistant director?” he was asked. “Why eat your heart out about the script? The songs are great and that’s all that counts.”

Not in Lanza’s book. He felt somehow that in Because You’re Mine he had let his fans down, especially since Because was the film which followed The Great Caruso; and he was determined to make The Student Prince as great as it could be. Lanza knows more about his type of music, his type of singing, more about opera than probably any other man at MGM. When his suggestions were discounted, when his requests were dismissed, when he felt he had been treated like a wayward little boy who chronically had to be chastized, he declined to continue with the picture.

That is the story, pure and simple.

He didn’t go crazy. He didn’t suffer a nervous breakdown. He didn’t leave his wife. He didn’t go to a sanitarium. He didn’t do any of the ridiculous things ascribed to him.

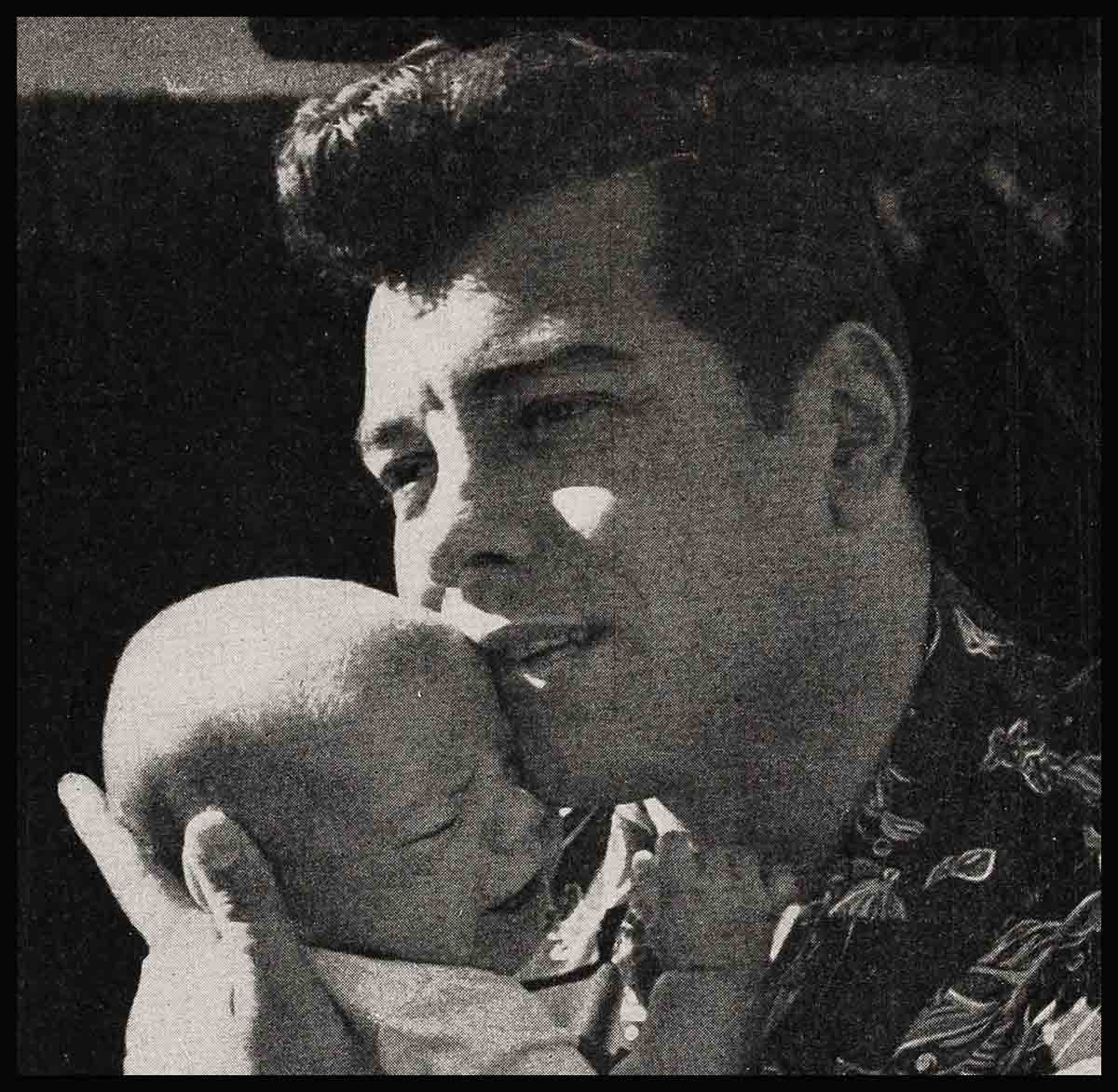

He thought over his course of action, and on the day his first son and third child was born, December 12th, 1952, he decided that he was right. There would be no compromise. The picture would be done extremely well, or he wouldn’t do it at all.

While the columnists reported that he was racing “all over Hollywood like a chicken with his head cut off,” Mario spent the first three months of this year down at Palm Springs.

“It was wonderful for Damon,” he recalls—that’s what the Lanzas christened their son. “We had him sleeping outdoors every day, and I honestly feel the fresh air and the warm desert sun really built him up. You know, he’s not one year old but still we have to dress him in one-year-old clothes. He’s really a bruiser. That boy of mine when he grows up—well, you’ll see. He’s going to be a big one. A man of integrity too.”

While they were down at the Springs, Betty and Mario tried eating out one night. Lanza was mobbed by hundreds of fans, many of whom kept clamoring, “What happened, Mario? Why are you and the studio fighting?”

After that, Mario remained on the Francis Ryan estate which he had rented for $1,500 a month. At midnight when the village was asleep he and Betty would ride around town.

For a while Betty used to say, “You know, Mario, maybe you should make a statement. Maybe you should explain your side. They’re saying so many awful things about you.” But Mario would shake his head and say, “No, Betty. Recrimination is a boomerang. Name-calling is childish. Let them call me anything they want to. I’m going to remain quiet. Eventually we’ll get everything worked out. Then there’ll be no hard feelings.”

Lanza who is supposed to have no public relations sense but has more than any other singer with the possible exception of Bing Crosby, proved that he was right.

Early in March he drove up to MGM and had a small conference with Eddie Mannix, the genial general manager. Mannix was surprised. “I’ve never seen you look so well,” he spouted joyfully. “You look like a 16-year-old kid.”

Mario said nothing about the fact that for weeks he’d been in crack physical and vocal shape, nothing about the fact that he had brought his own musical conductor, Constantine Colonicos, down to the desert, that together they had rehearsed 175 arias in 12 weeks. He said nothing about the fact that he had memorized The Student Prince script word by word and knew it letter perfect.

Mannix was so pleased at seeing Mario in such wonderful shape that he called to his secretary. “Get everyone in here,” he said. “I want them to see Lanza.”

Dore Schary came into the office and all the rest of the big boys. Everyone shook hands and it was agreed to let bygones be bygones. The Student Prince would start with a clean slate. There would be one or two more conferences between the legal beagles, and Mario would go back on salary as of April 1st.

Everyone agreed that under the circumstances The Student Prince would have to be made with infinite care, and that whatever errors were committed in the past would not be re-made.

If, at this reading, Lanza is not working on The Student Prince, and there is a very good chance that he might not, the reason will be that Mario wants any musically experienced director, while the studio insists on one director and one director alone whose great forte is not music. Mario’s representatives have advised him against accepting a certain director, and Mario will follow their advice even if it results in a long legal hassle and subsequent bankruptcy. His actions are always motivated by “what is best for the voice, and what is best for the public.”

When Lanza returned to Palm Springs a day after that reconciliation conference, he was riding on cloud 69.

“Where’s Damon?” he shouted, as soon as he rushed into the house. “Where’s my son? He’s got to hear the good news, too.” Miss Brown, the nurse, brought little dark-haired Damon into the family conclave. Mario explained to his wife and three children—he was very guarded about this—that his chances of singing for the public again were very good. If the studio would just give an inch, he would give a mile. All he wanted to do was sing.

That’s all Mario Lanza has ever wanted to do. He loves to entertain, and he was born to sing, and if he can’t use his voice for the public, a terrible frustration seizes him and he plunges into despair.

There are many actors and actresses in Hollywood who genuinely hate to act—no names, please—and they perform for only one reason, money. They take the money and buy television stations, motion picture theaters, oil wells, and magnesium mines. Their hearts are not in their work; they’re in the loot their talent brings.

With Lanza it’s different. He’s not interested in money. If he had been, the state of his finances would not be in their current, sorry condition. His primary interest is in singing, in bringing good music to the world, in popularizing the classical and semi-classical. And fortunately for him, he has a wife who agrees with his viewpoint. She wants security for her children—what mother doesn’t?—but under no circumstances will she permit Mario to jeopardize his voice or his career for “an easy buck.”

Friends tell the Lanzas they’re crazy. “Took at Ezio Pinza,” one agent told Mario. “He’s getting 10, 15 grand a week. Maybe you won’t believe this, but I can get you $30,000 a week to sing at Las Vegas.”

“I know,” Mario said. “They’ve already called and made an offer, an even higher offer. I told them no. I just don’t think the public would like it, not the people in Vegas, but music-lovers everywhere.”

The booking agent was incredulous. “You got rocks in your head,” he said flatly. “Nothin’ but rocks.”

Mario Lanza is one man who knows what he wants; and it just doesn’t happen to be money.

He wants the public’s friendship and respect and following; and he knows he has earned that only through the proper use of his voice.

To mis-use that voice for the grasping of “the easy buck” either in gambling casino’s or Grade B pot-boilers—well, as he says, “I’d sooner go bankrupt.”

That’s the attitude that makes Mario Lanza more than a rare talent—it makes him a rare human being.

THE END

—BY JIM NEWTON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1953

No Comments