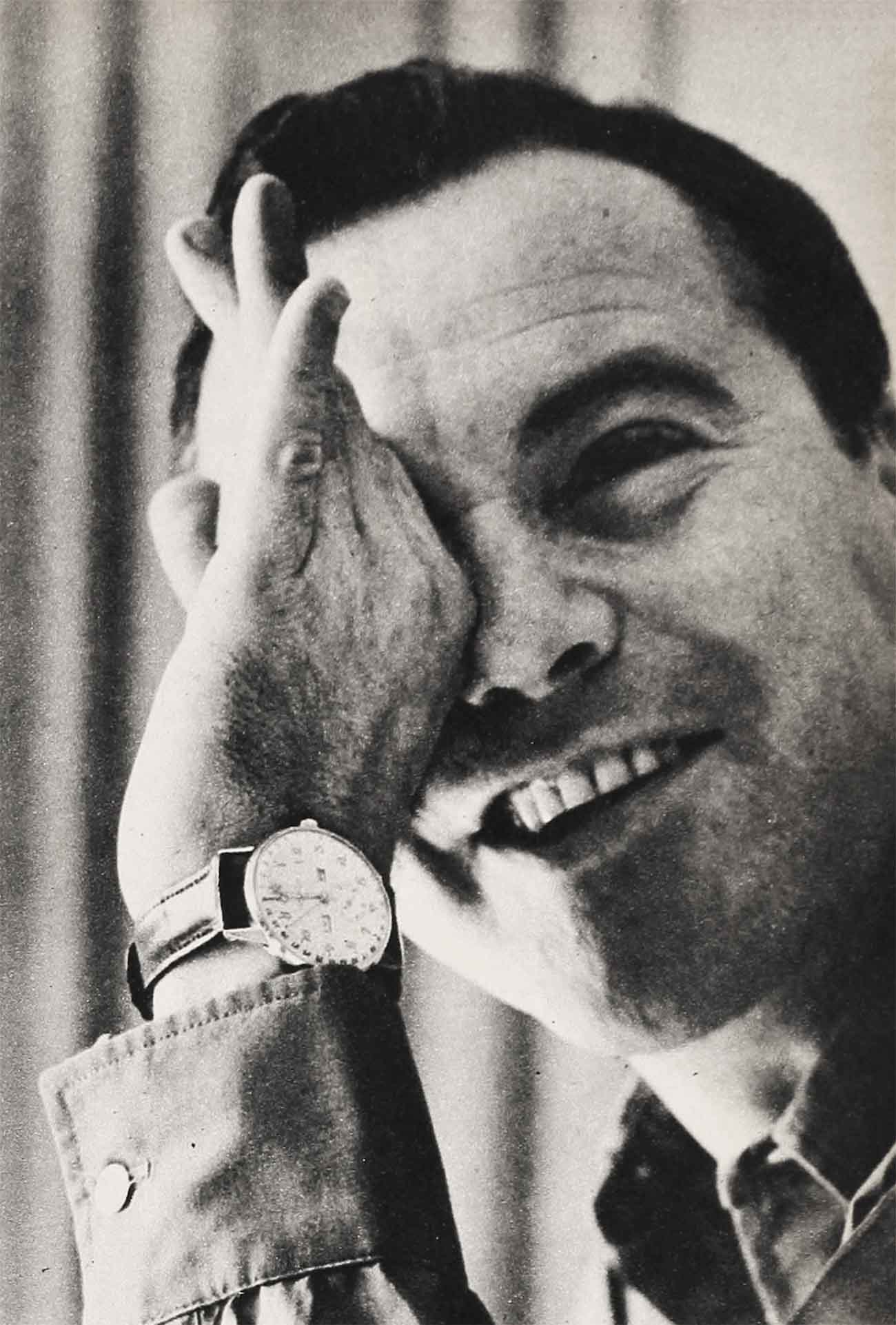

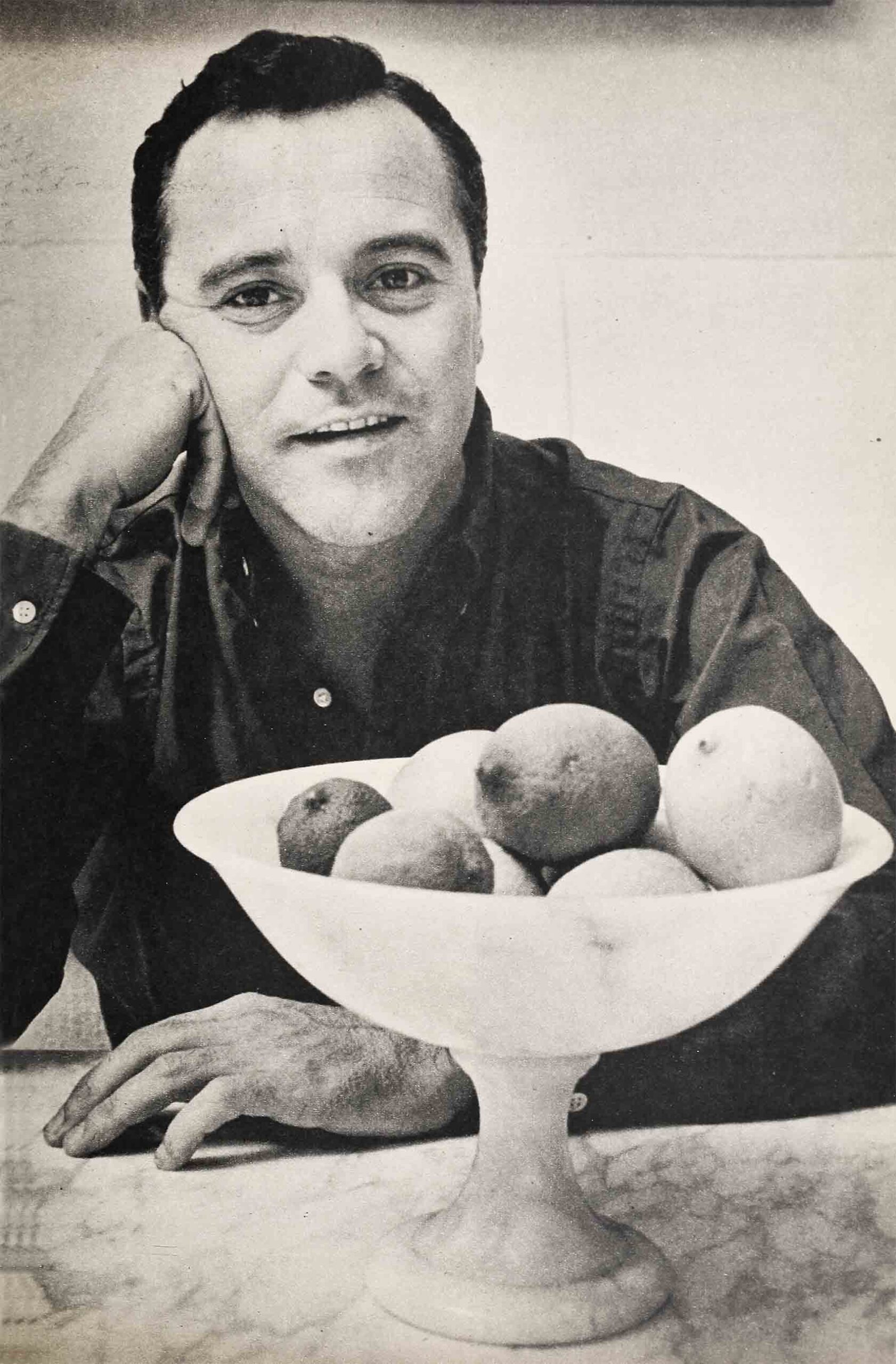

“A Man Can’t Win”—Jack Lemmon

What I have learned about women from women is that the more I know about people the less I seem to know about women.

I am confused. I think that every male is confused. If he isn’t, he should be.

Man’s very first association with womankind is unsettling. Customarily, he awakens in the arms of a strange woman. She reassures him by uttering friendly sounds and regarding him with an expression of possessive affection, but a certain amount of shock remains.

I have been exceptionally lucky in the mother department. I drew a lady who is sensible, ordinarily unsentimental, and equipped with a sense of humor that many a professional comedian would be ready to buy with diamonds.

She was christened “Mildred,” but her intimate friends call her “Min” in fond recollection of the rescue-oriented wife of a comic strip character named “Andy Gump.” When “Andy” had fouled himself up—well past the extrication powers of the ordinary male—he was always shown in the final frame yelling, “Oh, MIN.”

My “Min” is a genius at rescue, but she is also a wack. She spends from six to eight hours per day attending to my business problems. When I leave town, I sign a series of checks in blank and leave them in her care so that she can pay the utility bills and such. “And such” covers some interesting territory.

When I was out of town last summer, I received a charming thank-you note from her, expressing her appreciation for the birthday gift I had “given” her. She went blithely on with other news, but in the postscript she returned to the item that had excited my curiosity. “It was something I have always wanted,” she wrote. “A brass and glass tea cart. I’ll make good use of it and I think it was very thoughtful of me to buy it for me, saving you all that time and trouble.”

From Min, I quickly learned that the single most important attribute that a woman can bring to a human relationship is a sense of humor.

We both needed this basis of operation in the midst of my first serious romance. I was seven, and she was my second grade teacher, a glistening blonde with blue eyes and long, golden eyelashes. Do you know that I have never learned the words of “America” simply because, in the grade I was supposed to learn it, I was so mesmerized by sight of the teacher that I turned off my ears.

When stuck, I sing, “America, America, America, America.” The rhythm is wrong, but in memory’s eye I can still see that second grade teacher and I forget where I am or how many years have passed since she up and married another man.

But I learned more than the perfidy of women from her. She taught me that there is a conspiracy among women that no man can hope to understand or to circumvent. I used to stay after school to erase blackboards, dust erasers, empty wastepaper baskets, and—let’s face it—to stick around the teacher’s desk as long as possible.

She dug the routine. She was gentle and understanding. She used to walk me home, and sometimes she stayed to have tea with my mother. I soon began to notice the knowing looks and indulgent winks that passed between them; I couldn’t have explained it in words but I had caught onto the fact that no man can hang onto his dignity when caught between two women; no matter how amiable their intention.

I was in prep school, madly in love with a girl going to Abbott Academy, when I learned another lesson about women: a man can never anticipate a girl’s reaction in the face of any given circumstance.

Any reasonably bright guy can depend upon what a dog will do. A dog has a fairly predictable reaction pattern. Even a raccoon can be relied upon to show up every night at the same time and tip over your garbage can. But no man with a grain of sense will ever try to predict the behavior of a dame.

The morsel in whom I was interested invited me to attend a school party as her escort. When I reported to the school and caught sight of my date, I stood there for a full minute with my chin quivering on my tie. She was enough to make a marble statue flip. Well, between the perfume she was wearing, the way she looked at me from under lowered eyelashes, the moonlight on the terrace where we were not supposed to be, I kissed her. I thought I was getting a certain amount of cooperation—until pow!—she slapped me. End of romance. She said she never wanted to see me again. I was not to call, not to write, not to annoy her in any way. That ended the evening. I felt like a great big bully.

The following night I was gnawing on a pencil, trying to compose a persuasive note of apology, when the phone rang. It was Lady-Touch-Me-Not, and she inquired plaintively, “Why aren’t you here? I thought we had a date for both Friday and Saturday night. I’ve been ready for an hour.”

You figure it out.

She went on to try men’s souls, and I went on to college.

Being me, I fell in love with a girl living in New London, Connecticut. If true love is the kind that doesn’t run smoothly, all I can say is that our romance made that skirmish between Romeo and Juliet seem like an exchange of glances between two strangers in a crowd leaving a football stadium.

There came a day, following various misunderstandings, when Miss New London telephoned to tell. me that she was lonely and dejected, and that she yearned to see me. Her words and tone were those of love incarnate and I almost squeezed the telephone to death. She said that if I couldn’t get to New London, she would hop a Boston-bound train.

Voom. I said I would borrow a car and pelt south as fast as gasoline would take me.

It was a noble idea, but it turned out that everybody had made plans for his wheels over that weekend. Finally I located a friend whose family had a spare car on the back lot. It was up on blocks, the motor being used to provide power for an electric saw to cut the winter firewood.

We reinstated the Ford as transportation by stuffing rags in the radiator (no cap), inflating the tires, filling the tank, and shrugging off the fact that its wooden body rattled like shutters in a hurricane.

I made it to New London with no casualty except an occasional pedestrian who laughed himself to death as I rolled past him.

My girl came downstairs dressed for, say, an Assembly Ball, so she didn’t find my chariot amusing. Even so, she did permit me to drive her to the party, but I was still checking our coats when she disappeared among the dancing millions. Occasionally, during the evening, I caught a glimpse of her, laughing and living it up, but showing absolutely no outward sign of her previously reported longing for Lemmon.

At eleven-thirty—not having danced with my girl once—I took off for Boston in low gear. It took that cukie car ten hours to cover the distance traveled by the milk train in three.

Naturally, Miss New London telephoned Sunday afternoon, furious. “I don’t understand you,” she said. “Why were you so cold and indifferent? Where did you GO?”

And so I came to Hollywood where the lessons to be learned about women are queen-sized. For instance, outside of Hollywood, it is assumed that glamour is the first interest of an actress.

Recently I finished a picture called “It Happened To Jane,” with Doris Day, Ernie Kovacs and Steve Forrest. In that one, Doris spends most of her time in levis, a plaid shirt, a tousled topknot, and a faceful of freckles. Great girl, Dodo. Her idea of a happy moment was lying in the sun between takes in order to collect another freckle. Very confusing Hollywood type: doesn’t smoke, drink, or nightclub; just works, runs her home, and loves her husband and son as if she lived in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.

Another recent effort of mine was a picture entitled “Some Like It Hot,” starring Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, and Joe E. Brown. In a script as involved as female logic, Tony and I wound up wearing girls’ togs in the midst of a girls’ orchestra.

Do you know what everyone who has seen the picture has asked me, “How did it feel to be a girl?”

I can tell them. Cold.

When Marilyn overheard my answer she gave me one of her ripe grape smile and cooed, “But no real girl is ever cold.

What I learned about Marilyn from Marilyn is that the cliche about beaut and brains never being bundled together blew up on the launching pad.

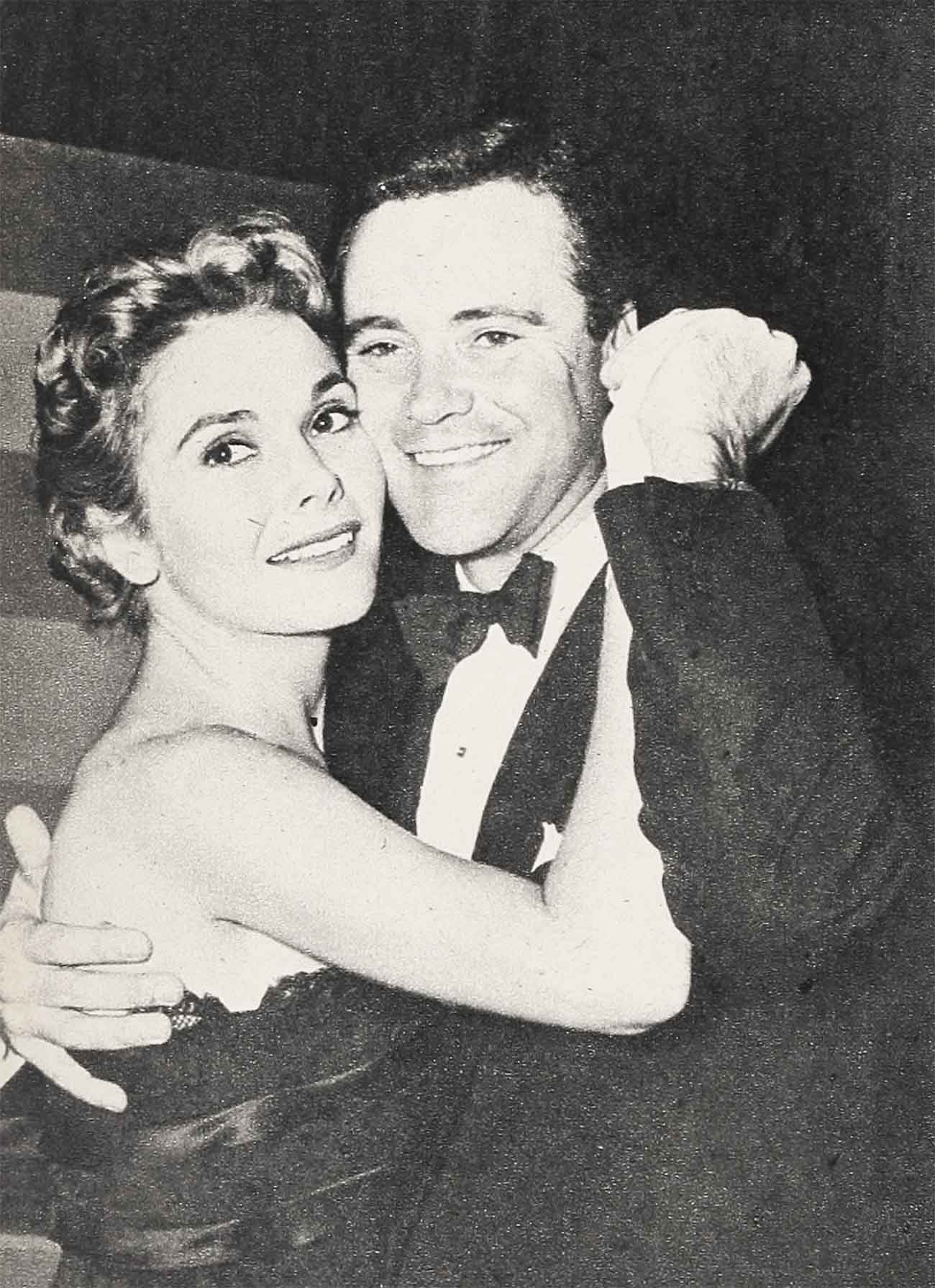

Finally, I’d like to point out that then is nothing to equal the ability of-a cleve woman to reduce the balloon of a man importance to a mere squeak of hot air. One night not long ago, I was having dinner with Felicia Farr and several other workers in the film industry. I have some ideas about solving the problems of the picture business, and occasionally I’m inclined to air them.

I had held forth for several minute when I realized that I was making speech. I decided to come off it, and said “Well, that’s it. I’ve had my say and give you my word that I won’t mention show business for the rest of the evening.

Felicia spoke the line that blew off the roof. She said with patient sweetness an resignation, “Promises, PROMISES.”

I tell you: a man just can’t win. But then, who really cares about that? It’s trying to win that’s fun.

THE END

—BY JACK LEMMON

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1959