The Starting Point—Robert Wagner

Today, Bob Wagner is a man in his own right, the hottest young male star on the 20th Century-Fox roster and an idol of a million teenagers. His studio has invested fortunes in his pictures; his fan mail averages thousands of letters each week. He is a success, a Big Name, a power at the boxoffice.

To understand Bob’s success, you must return to the place he calls home. Not to the small two-bedroom apartment that the studio only recently got for him, but to his parents’ home in La Jolla. And to understand Bob you must also meet his parents.

“One thing: I’ve noticed about Bob,” remarked a close friend at his studio, “is how much more at home he feels when his father and mother are around. He seems gayer, more relaxed, more fun-loving. I remember once, when we were on location in Arizona for ‘Broken Lance,’ Bob got word that his father and mother were coming down to spend a week. Until they arrived he was like a race horse champing at the bit. I said something about how eager he must be to see his folks again. ‘Well,’ Bob dissembled, lest I see how deeply he felt, ‘Dad just got a new Cadillac, and I’m sort of anxious to drive it. Dad says it’s a honey to drive.’ ”

Not that Bob’s parents ever coddled him. He was loved but not spoiled. His sister, Mary Lou, four years older than Bob (she’s now Mrs. Albert S. Scott, Jr., mother of three youngsters and married to a Claremont, California engineer) has never taken a public interest in Bob’s career, nor has she ever visited the studio.

“Mary Lou,” Bob once said wryly, “can set me back on my heels faster than anyone I know if I ever get too cocky. She never flatters me. She really tells me what she thinks when I give a bad performance. Even my six-year-old nephew once cut me down to size. I had gone over to Claremont to bring the kids some presents. No sooner did I step into the house when my nephew floored me by saying, ‘Mom took me to see your movie. And you know something, Uncle R. J., you’re a ham!’ ”

It was Bob’s mother, gentle-faced, quiet and deeply religious (she is a follower of Unity) who explained how Bob Wagner first became R. J. “Mr. Wagner was always Bob to me and our friends. When our son came along and was named after his father, there was no thought of calling him Junior. Almost automatically he became R. J., and that’s what he’s been ever since, at home, at school and in our family.”

Even Wagner himself, calling a friend on the phone, will say, “This is R. J.” It is almost never Bob with anyone he knows well.

Bob’s father, Robert J. Wagner, Sr., is about sixty—a bluff, hearty, self-made man who came up the hard way as a paint salesman in Detroit. When angered, he can roar like a wounded bull. Some of Wagner, Sr.’s explosive temper came down to his son, but R. J., like his old man, gets over his anger quickly. “I was never afraid of my parents,” Bob will tell you today. “When I was a kid and they had friends over in the evening, I wasn’t shushed away. They let me stay up as long as I liked, within reason. And the worst punishment they ever did or could give me was a disappointed look.”

And the elder Wagner, whom his son calls “The Dude” or “Junior,” out of love and affection, says, “We always gave R. J. his head and backed him up in whatever he did. When you treat a boy like a man, that’s what he becomes.”

A studio production man recalls an interesting sidelight on Mr. Wagner’s attitude towards his son’s career. It was on the day that R. J. and Richard Widmark had their slashing, bloody battle on a mountain ledge for one of the key scenes in “Broken Lance.” Bob’s parents were there watching the scene being shot. This was a tough, bruising, realistic fight among the granite boulders of the mountain, and both Widmark and Wagner suffered lacerations from their struggle. Mrs. Wagner watched the scene for a few moments, then turned and walked away, white-faced and visibly disturbed. Her husband stayed on, grimly taking it all in.

When one portion of the fight was over and the cameras were being readied for the next take, the production man turned to Mr. Wagner. “It’s a sort of rough business, isn’t it?”

“I know,” Mr. Wagner said, quietly, “but life is rough, too. R. J. has to learn how to take it.”

What makes the elder Wagner proudest of his son’s achievement is the new and more respectful attitude towards R. J. among Mr. Wagner’s associates in the steel business. “To them, R. J. was just a kid who was in the movies for a lark,” recalled Mr. Wagner. “They remembered him as a bright, smiling youngster who called, soliciting their orders during the time he was with me in the business. When he got into pictures they said very little, knowing I wasn’t too happy about my son’s new career. Then, one day, a couple of weeks ago, I stopped in to see a customer. The first thing he did was tell me he had just seen ‘Broken Lance.’ ‘Say,’ he said, ‘that boy of yours is darn good! He’s really come through, hasn’t he?’

“Well,” Mr. Wagner went on proudly, “that was one of the greatest things that’s happened to me.”

It has always angered R. J. to pick up a magazine and find himself described in an article as the son of a “millionaire steel tycoon.” “How silly can you get?” asks Bob. “My father is far from a millionaire.”

The elder Wagner is just as vehement. “I’m a long, long way from anything like that,” he snorts. “Sure, I’ve made a few bucks, but I’ve worked for it. It didn’t come to me on a silver platter. R. J. didn’t get it the easy way, either. He sold papers, washed dishes, shined airplanes and took care of horses to get money for the things he wanted. That was because, long ago, I had made a deal with him. Every dollar he earned, I’d match. It turned out to be a pretty costly arrangement for me. R. J. was a hustler. He kept a little black notebook and jotted down every dime he made.”

Yet it’s Bob’s mother, who was a private secretary in Detroit before her marriage, who feels most keenly any criticism leveled against her son. She delights in R. J.’s success, like any proud mother, but she still cannot understand some of the things that go with it. “Even in La Jolla (a little sea-coast town about 125 miles from Hollywood) we get phone calls for R. J. from youngsters all over the country,” she revealed. “And fan letters, letters by the hundreds. I don’t know how they ever ferret out our address. It’s nice to know R. J. is so popular, but some of the silly things they’ve said in the gossip columns worry me.”

Bob himself has concluded, in the maturity of his twenty-four years, that his only protection against malicious or silly gossip is “to be good up there on the screen. Sometimes,” he says, “Mother would read some of those magazine articles and get terribly upset.

“Why do they say those things about you?’ she’d ask.

“And I would tell her, ‘Mother, somebody’s always gossiping about actors. It’s a favorite indoor sport, part of the picture business. I’m not worried, so don’t let it get you down.’ ”

It is true, as Bob says, that like any successful actor he has had his share of gossip, of venomous digs and sheer fiction. There are always two sides to every story, as a certain singer named Johnnie Ray well knows.

“All I can tell you is that this Wagner boy is just about the greatest,” said Johnnie. “He must have had a wonderful background to be the way he is. I remember when I first came to 20th to test for ‘There’s No Business Like Show Business.’ Man, I was scared. It was my first picture and I was shaking all over. I’m on the recording stage, trying to get myself together to record my first number, when I see this tall, blue-eyed chap standing off to the side. I recognized him immediately. Then suddenly he walks over, sticks out his hand and says, ‘Johnnie, I’m R. J. Wagner, and I want to wish you the best of luck. Go ahead and kill ’em.’

“Well,” Johnnie continued, “having Bob do a nice thing like that got me up there and helped me forget all my nervousness and jitters. I sang the way I wanted to. And it was all due to Bob. I’ll never forget that pat on the back as long as I live.”

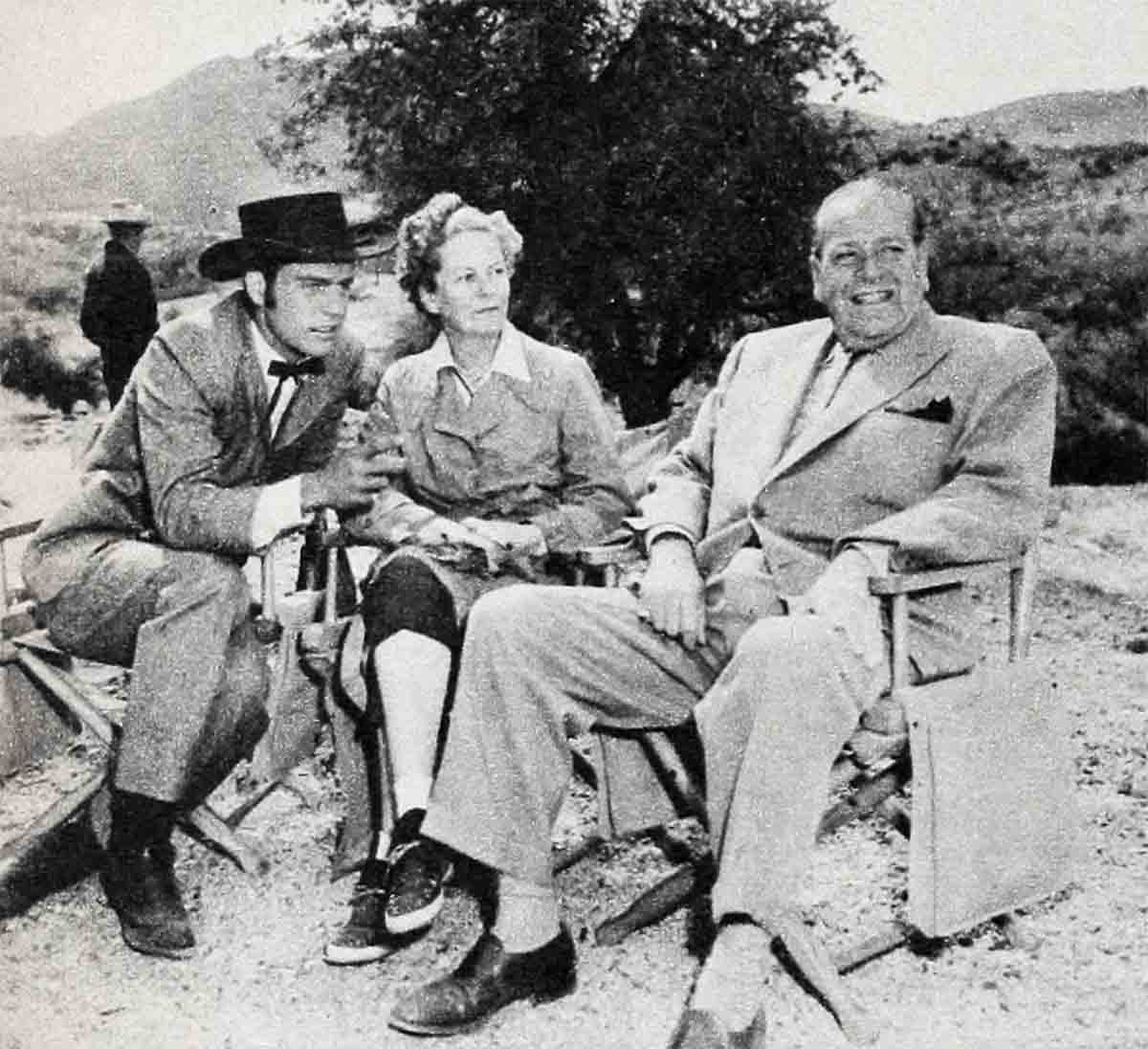

One of R. J.’s idols in the picture business is the tough, sardonic Spencer Tracy, whose son Bob played in what critics still say is R. J.’s best picture, “Broken Lance.” It was Tracy who recalls the day on location near Nogales when he was lolling back in his chair, with his wide-brimmed Stetson pulled low over his eyes against the hot Arizona sun, amusedly watching the assault of a group of local girls on his young co-star. The girls were pretty and eager and R. J. was responsive. “You know,” drawled Tracy, “that was the day I began to understand how Wally Beery used to feel about me.”

It was also Tracy who remembers how well Bob took a bit of sharp repartee that had R. J. on the receiving end. It happened after the “Broken Lance” company had returned to the home lot following some weeks on location. Bob had been designated by PHOTOPLAY magazine as “The Most Promising New Actor of 1953,” but because he was away, Janet Leigh had accepted the honor for him at the Gold Medal Awards banquet. Later Janet brought the plaque over personally and gave it to Bob on his return.

Pretty excited, young Robert took the award to Spencer Tracy’s dressing room. Although he holds Tracy in a respect that amounts almost to awe, R. J. kiddingly said, “See this, Mr. Tracy. That’s what they think of me! I just want you to know the kind of actor you’re working with.”

The gray-haired Tracy looked Wagner up and down unsmilingly, except for a twinkle in his eye. “Yeah, kid,” he drawled, “I know how you feel. I felt the same way the time I got my first Academy Award.”

“R. J. laughed as hard as anybody,” Tracy chuckled, “and he’s still telling that story around.”

It is quite true that R. J. has always shied away from talking about his dates or his romances. As Bob himself says, “If I go out with one actress a few times, it’s a romance. If I date a lot of different girls, then I’m a Casanova. It’s one of those ‘heads-you-win, tails-I-lose’ deals. So I date in out-of-the-way places.”

But one of Bob’s oldest friends, a girl with whom he went to grammar school and junior high, explains it further. She is a pretty, blue-eyed blond named Virginia Hunter, now the mother of a two-year-old youngster. “R. J. and I have known each other ever since his family first moved to California. We lived nearby in Bel-Air; his mother and mine still go to the same beauty parlor. We became pals as kids because we both loved horseback riding. I’m athletic; Bob was always a fine athlete. I’ve known him for eleven years, and though he never really had one girl for long periods of time, I suppose I could say I was friendliest with him. He was rather a lone wolf in those grammar school and junior high days. He was always friendly and laughing, but he only had a few close friends. I guess I was his closest girl friend.

“When he was at Emerson Junior High he came to tell me he was going to his first formal and didn’t know how to dance. I put some dance records on the phonograph, and we practiced and practiced until he was perfect. Today he’s a wonderful dancer. R. J. always came to tell me his troubles; he’d explain that a girl he was dating in high school had serious intentions of going steady. How could he get out of it? He’d only meant to be pleasant. I explained that he was so interested in everything, complimented a girl so well on her clothes, her perfume, her sports ability and so on, that any girl would assume much more than he really meant. He was always one to avoid entangling alliances, to keep things on a friendship basis. When a girl got serious, that was R. J.’s signal to run.

“With most people R. J. rarely lets himself become really friendly, but with me it was a sympathetic brother and sister feeling. As kids we’d often go to Palm Springs with our families for the holidays. Our hotel always served breakfast at a certain time. All of us would rush in at the very last moment, but R. J. would always take time to go from cottage to cottage, waking up the other kids. He knew how starved we’d get if we missed breakfast.

“Like other boys his age, he used to love hot rods and motorcycles. I’ll never forget the time he came to my house with his cycle; I was dubious, but game, and went riding with him. But only once, mind you. I’ll never forget that ride.”

As a child, Virginia explained, she appeared in a number of pictures at 20th; later did radio and Tv and currently has a role in the studio’s musical “Daddy Long Legs.” Since R. J. knew Virginia was acquainted with show business, he often came to her for advice. “I know,” says Virginia, “that R. J. hasn’t let his success go to his head. When he came to me and said he was getting the title role in ‘Prince Valiant,’ he was absolutely starry-eyed and unbelieving.

“Imagine, he kept saying over and over, ‘Mr. Zanuck is putting me in it. It’s going to cost three and a half million bucks, hear that! Three and a half million bucks and he’s putting me in it!’

“ ‘Why not?’ I asked him. ‘You’ve demonstrated you can do it. After all, Mr. Zanuck’s not going to take some unknown extra and entrust him with that role!’ ”

There’s still another Virginia who knows R. J. well—lovely, intelligent Virginia Leith, who made such an impression in her first 20th picture, “Black Widow.” Miss Leith was loaned out with Wagner to Panoramic to make “White Feather”; it was a rough, illness-ridden location in Durango, Mexico, and she had ample time to study R. J.’s reactions.

Virginia recalls that she had met Bob before. She made a test with him at the time he was just starting at 20th, and she can still remember that occasion. Bob was attempting the role of a lawyer and had to wear a judicial white wig. It was an oddly amusing test but even then Virginia thought, “This boy is good. He’s going to make it.”

But it wasn’t until Miss Leith worked with R. J. in Mexico that she realized how much he had matured. “All the time R. J. was there,” Virginia said, “he was deeply and genuinely moved by the poverty he saw in the mountain villages. It affected him deeply. Then one day a little Mexican boy started hanging around our company—an orphan, cross-eyed and desperately poor. R. J. bought the boy clothes and food and began looking after him. Then without a word to anyone, R. J. had the child admitted to the local hospital, got a fine doctor and arranged for an operation to straighten the boy’s eyes. The day before we were to return to Hollywood, R. J. asked me to go to the hospital with him to visit the little boy after the bandages were removed. The whole thing was a complete surprise to me. Neither I nor anyone in the company had known a thing about it. When I saw the boy, his eyes were now straight and perfect.”

It is characteristic of Bob to express his gratitude to people in concrete ways, often with costly gifts. He is constantly giving albums of his favorite Jackie Gleason records to people who haven’t heard the records before. To Eddie Dmytryk, his director on “Broken Lance,” he gave a gold cigarette lighter emblazoned with a miniature of the Indian lance used in the picture. For Betty Lou Fredericks, his hairdresser on “Valiant,” he ordered a gleaming gold pin of the profile of Prince Valiant, complete with golden wig, and on the reverse of the pin he engraved a line from a favorite song. The engraving read, “Do you realize I need you? I want you near me always.” And it was signed, “Gratefully, Val.”

When he discovered that Monica Moran, teenage daughter of character actress Thelma Ritter (with whom Bob worked in “With a Song in My Heart”) was born on a Tuesday, Bob was at his jeweler’s the next day. He remembered the little verse that goes in part, “Tuesday’s child is full of grace,” so he bought a heavy gold charm for Monica’s bracelet, with a graceful Tuesday’s child perched on a pearl. And for his mother’s birthday and thirty-second wedding anniversary, he ordered a fabulous dinner at Romanoff’s, invited both his parents, then presented Mrs. Wagner with a diamond and pearl pin in the shape of an angel. On the back was engraved, “Because you’ve always been an angel to me.”

R. J.’s dad shook his head over this. “He just never seems able to do enough for us, especially his mother,” he said. “Sometimes I think he does too much. We don’t want him to spend his money that way, but we can’t stop him.”

It could be, of course, that R. J. in doing so much for his parents, is trying to atone for the disappointment he caused them in passing up the steel business. R. J. has often said, “I know Dad was terribly upset when I wanted to go into pictures—just how disappointed I never realized until later. I had hurt him, but I didn’t understand it then. You know, it takes kids a long time to realize that their parents usually make good sense. Now, of course, Dad thinks I’m just about the hottest thing since John Barrymore. I have to keep telling him that I still have a long way to go.”

Yet, if he still has a long way to go, Bob is aware that he will always have his family behind him, that through them he can always replenish his spirit. As a close friend said, “Bob’s parents gave him his head and the confidence to use it. They’re not losing any sleep about what fame will do to him, nor are they worried about his going off the deep end. About the farthest he’ll go is straight home to a golf game with the old man and to his mother’s cooking.”

And therein lies his strength, for the years to come, until he marries.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1955