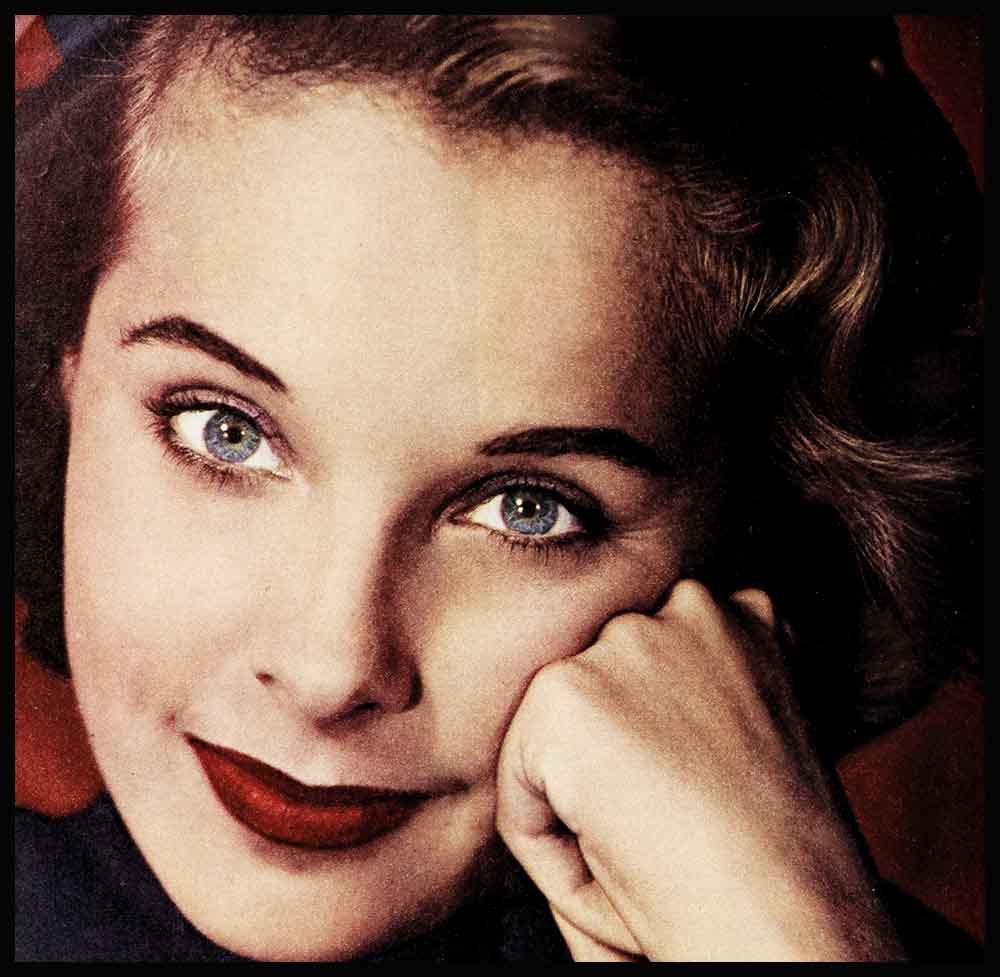

Unpredictable Mona

Hollywood is used to being set back on its heels. It’s a town where almost anything can happen—and it very often does.

But even that shockproof town was more than a little taken aback, when Mona Freeman, a girl whom everybody had pegged as the perfect mother and the perfect wife—and almost the ideal homebody—kicked over the traces after six years of what appeared to be the happiest of marriages to Pat Nerney.

People shook their heads in amazement—and then they shrugged. “Well, after all,” they decided, “you never can tell what really goes on inside of people—deep inside.”

Not even those who are reconciled to the idea of the separation, however, can become accustomed to the new Mona they’re seeing around town—a girl who has definitely gone on the glamour kick. Though she seems to be loving it, the general feeling is that Mona may not be quite as happy as appearances would suggest in this new role.

All the cliches have been pulled out—no stops:

“She’s playing with fire—that little girl is.”

“She’s swimming in mighty deep water—and that can be dangerous.”

AUDIO BOOK

People just can’t get used to the Mona who is busily doing the rounds of the gay night spots with a series of sophisticated—and some say unsuitable—escorts. And they can’t get over the feeling that by turning her back on Pat Nerney, who certainly gives every indication of loving her as deeply as he ever did, that she’s turning her back on a life that can be rich and meaningful.

Seldom has a Hollywood divorce created so much sympathy. Seldom have so many people wanted so much to see the couple reunited—to see them being mother and father again—together—to their charming little daughter, Mona, Jr. And seldom has Hollywood been less sure what the ultimate outcome will be.

This split, unlike many in Hollywood, is not a direct result of the wife’s career. The trouble between Mona and Pat developed as they themselves grew into different people—quite different from the pair they had been when they took their vows at the altar of a Catholic Church.

From all reports Mona is the one who has changed most, but this does not necessarily mean that the change should be held against her. She was nineteen when she married Pat, and she married him a very short time after their first date. There was little time to learn anything about him, other than that he was one of the sons of the well-known Ford dealer in Los Angeles, that he had an enchanting sense of humor, that he boasted red hair and freckles and was, like Mona, of Irish descent. To Mona’s mind it was a perfect combination, adding up to love.

Last April, after six years of marriage during which their daughter Mona, Jr. was born, the Nerneys parted. In September, despite Pat’s attempts at a reconciliation, Mona was granted an interlocutory decree. At approximately the same time she was tested at RKO, whereupon studio boss Howard Hughes handed her a forty-week contract at $1,000 a week. Mona moved out of the home she and Pat had built in the Pacific Palisades and into an apartment closer to the studio. Since then she has been seen in restaurants and night clubs, both well-known and of small repute, with a varied assortment of men, ranging from Nicky Hilton to Bing Crosby. The consensus of opinion is that Mona is becoming sophisticated too quickly.

Those who ladle out this opinion include both old friends who have known her for a long time, and columnists who have met her only briefly. Yet there is some defense for Mona on this score.

The change she underwent during her marriage was the simple evolution into maturity. She had been little more than a child when she married Pat, and during those six years of adjustments and her subsequent motherhood, Mona became a woman. Few people noticed it, because her physical appearance did not change. Mona’s prevalent wail against Hollywood ever since her first contract with Paramount in 1943 has been the refusal of producers to allow her to play grown-up roles.

Her fragile figure and piquant features have always made her look much younger than she is, and she got off to a bad start when she tested for, and lost, the role of Barbara Stanwyck’s kid sister in “Double Indemnity.” Mona was then seventeen, and supposed to look seventeen, but on the screen she looked twelve.

Soon afterwards, she got the role of the twelve-year-old in “Dear Ruth” and turned in such a sock performance that from then on she was thought of as a child, not only by producers but by the entire town of Hollywood.

At nineteen, she felt desperate about her career, and she turned her mind away from the problem only temporarily when she fell in love with Pat. She first dated his brother John, and met Pat the day John took her home to meet his family. Mona wasn’t very impressed until the night six months later when Pat joined Mona and his brother for an evening at the Mocambo. Pat was amusing; he was kind and thoughtful; and he seemed to put women on a pedestal. Mona switched allegiance almost in an instant, and after a whirlwind courtship they were married.

Now, she thought, people surely would accept her as a young woman rather than a child. But they didn’t. Mona continued getting kid-sister roles, and even after her daughter’s birth two years later, the situation did not change. She tried everything. She switched make-up, bought slinky clothes, tipped her weight forward on the highest of heels. Meanwhile, Pat Nerney was perfectly satisfied with Mona as she was. Because Pat, while a good five years older than Mona, was not a sophisticate in any sense of the word.

He was a boy whose wants were simple and whose life was no more complicated than a volume of The Bobbsey Twins. He had grown up in a family untouched by the insanity of Hollywood, and he was described by those who knew him as “a soft-spoken, well-bred, and well-balanced boy.” Pat’s sole surrender to Hollywood’s influence had been his penchant for dating young girls in the industry. Both he and his brother John confined their premarital dating almost entirely to starlets, and it is said that Pat’s fascination with the idea of associating with movie people was responsible for his easy attitude toward Mona’s career.

The one hitch in the setup was his inability to understand the demands of such a career. Mona is an unusually prompt person, and as she matured, she became even more conscientious about her work. When there was a call to be at the studio early in the morning, she would by-pass a social evening and get to bed early the night before. But Pat, who always loved a gay evening and could afford to sleep a little later, wanted to paint the town.

This small difference between them was not in itself important, but it is typical of the many small ways in which they began pulling in opposite directions. Mona had grown up more quickly than Pat. As a friend said recently, “Pat has a cute, boyish sense of humor, the kind of thing a girl could fail in love with, but not live with day in and day out.”

When they were building their home after little Mona’s birth, they went out to the lot every day and watched the workmen like a couple of gleeful kids. The day the floors were laid down, Pat took a phonograph and records along and whirled Mona around the floor despite the gawking passersby. It is an example of his natural exuberance, a trait which would charm a youngster, but embarrass a girl who was trying to prove that she had grown up.

Because Pat’s income is upper middle-class, that is the way they lived. For the first four years of their marriage, they lived in a Westwood apartment that was so small the baby’s nurse had to sit in the bedroom when the Nerneys had guests. Pat laughingly met the necessity of having to change his clothes in a closet off the dining room. It was a life that was merry and wonderful for an average couple and perhaps would have continued to be so had not the glamour of Hollywood’s lusher living been hanging over their heads.

When little Monie was two, Pat and I Mona built their house, scraping together every cent in order to swing the deal. Mona was as positive about the things she wanted in the house, such as a sunken living room and pine-paneled kitchen, as she had been firmly self-satisfied about the success of her marriage. Secure in the knowledge that it had worked out happily for four years, she had derided the break-up of other marriages around town.

But last spring, despite the new house and all its advantages, boredom began to set in. Some say that it was the result of Mona’s love of change; others, that she had matured beyond Pat; still others, that despite the fact that all her earnings went into savings and professional expenses while they lived on Pat’s salary, Mona was growing increasingly interested in that root of all evil, money.

At any rate, three things happened almost simultaneously. She left Paramount Pictures, she was given her thousand-a-week contract by Howard Hughes, and she announced that her marriage to Pat was at an end.

Hollywood couldn’t have been more shocked if the Robert Youngs or the Fred MacMurrays had separated. People recalled their visits to the Nerney apartment, remembered the three tiny rooms cluttered with happy evidence of their life together—Mona’s paintings, Pat’s photographic equipment, and small Monie, adoring both her parents. They remembered the newer life in the big house and the pride with which only recently Pat and Mona had furnished their new home.

There had been Mona’s insistence on cooking, even after she had worked all day at the studio, and there had been Pat’s thoughtful gifts to his wife. Above all, people remembered Mona’s repeated statements—“My husband comes first, always.”—“Many girls are willing to let acting break up their marriages, but not me!”—“I’m lucky I married Pat. If I’d married anyone else I don’t think I’d be married today. He’s so unselfish—”

And there was the poem she had written on a card that went with a Saint Patrick’s Day gift to him—“Roses are red, violets are blue, it’s the luck of the green that I’ve got you.”

Suddenly it had all gone down the drain. Pat tried everything he knew to mend the rift. Mona went off to Republic Studio to make “Thunderbirds” with John Derek, and the people who worked with her on that picture report that she was unusually quiet. “I wouldn’t say that Mona brooded,” said one, “but she had none of her usual sparkle.” Those who worked with her in RKO’s “Angel Face” made much the same comment.

While the marriage was still a going concern, a close friend had said of Mona, “One of her chief virtues as a wife is her affection for old-fashioned ideas. She doesn’t like night clubs. She’d rather stay home. Mona’s no frantic career girl, chasing around town after fleeting values. To her, Pat means more than any acting contract anybody could dangle in front of her.”

Yet, soon after she sued Pat for divorce, Mona climbed on the glamour bandwagon. It was almost as if she were determined, now that she was free and twenty-six, to prove she was twenty-six. She wore sophisticated clothes and went to sophisticated places. When she wasn’t working in a picture she frequented the town’s brighter night spots. She began leaving the home and hearth she had valued so highly during her marriage to Pat, and at this writing is still doing it. And that same friend has said regretfully, “It looks very much as though Mona has become a ‘frantic career girl’.”

She went to Palm Springs, desert playground of the stars, and dated Johnny Faunce, professional tennis player. Shortly after that, Bing Crosby arrived at the resort for the double purpose of recording his radio show and enjoying the local golf tournament. It was about this time that Bing began coming out of the shell of grief that had encompassed him since Dixie’s death more than two months before. He dated starlet Mary Murphy for a golf game, and then he dated Mona.

Mona was fourteen when she first was put under contract to Paramount, and she adored Bing from the start. Now, a dozen years later, she found herself his dinner companion. It wasn’t the first time. A few weeks before, Bing had taken Mona to an opening night at the Club Gala back in Hollywood. Now in Palm Springs, he took her to lunch at the Racquet Club, to dinner at the Chi-Chi, to another dinner at the Doll’s House. And they continued to see each other in Hollywood.

All this has raised eyebrows, naturally, and the press has closed in to comment. Mona has agreed to the reports that she has dined with Bing. “But I wouldn’t call it a romance. He’s an old friend. We’ve known each other for a long, long time.” Asked about Bing’s reaction to Dixie’s passing, Mona said, “I don’t think he’s gotten over that yet. It will be a long time before he does.

“We just had dinner a few times,” she explains. “We’ve talked about his kids, and mine. He’s very nice, and terribly amusing. He’s probably the nicest person I’ve ever known. But I’m sure he takes other people out,” she adds. “You can’t make a romance story out of this.”

People may not call it a romance story, but they realize that it does lessen the chance for a reconciliation between Pat and Mona. This was something everyone had been working for. As a married couple, the Nerneys had been immensely liked, and as individuals they have a great many friends. Almost without exception, these friends wanted to see Pat and Mona back together again. They went to him and they went to her and asked if there was anything they could do to help. And the answer from both was a polite “no-thank you,” tinged with wistfulness.

There was a ray of hope when, on New Year’s Eve, Pat and Mona went to Mocambo together. They saw each other often after that—sometimes for a quiet dinner, but mostly for conversation regarding their daughter Yet nothing happened.

Asked what he thought about the odds for a reconciliation, Pat Nerney said, “It looks very remote. I wouldn’t say no positively, because who knows what might happen with time? I couldn’t say, for instance, that in ten years Mona and I wouldn’t be together again. Nothing’s positive. But it’s remote. You might say we’re both satisfied now. I see little Monie quite often, and Mona’s wonderful about it—says I can see her any time I want to.

“I went to Europe, you know, after Mona started divorce proceedings. I really had myself a time. I loved it over there. Those Europeans have a way of bucking up a fellow when he’s feeling low.” And then he added, “I’ll never marry again. My religion, you know. But I’ve dated—there’s been Peggy Ann Garner, and Wanda Hendrix, and Coleen Gray and Martha Vickers. I love ’em all. But I won’t get married again.”

He spoke willingly about it, and he sounded very much like the young man he is reputed to be, soft-spoken and polite. And he also sounded quite sad.

As for Mona, she is on the merry-go-round and when she’ll stop nobody knows. The divorce will not be. final until September 25 of this year, and as Pat says, nothing’s positive. In the meantime, Mona is leading the kind of glamorous life that is attributed to Hollywood stars. She is seen with wealthy and influential men, and while she is twenty-six, a fact which even her close friends tend to forget, it does seem that they and the columnists are right. Mona is traveling too fast in her new world of freedom, going at a pace where happiness is seldom found.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1953

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments