Malarkey On The Midway

“STEP RIGHT UP, FOLKS! Only a dime! Try yerr luck!”

There is something about the hoarse yell of the carny barker that strikes an irresistable chord in human nature. As Dr. Edmund Bergler, writing on the subject, says. “Every person in our culture is a potential gambler.”

But though the good doctor’s got the right idea, he’s got the wrong terminology — because there is no such thing as a gambler; there are only operators — and suckers. And the best place to see both close up is along the carnival midway.

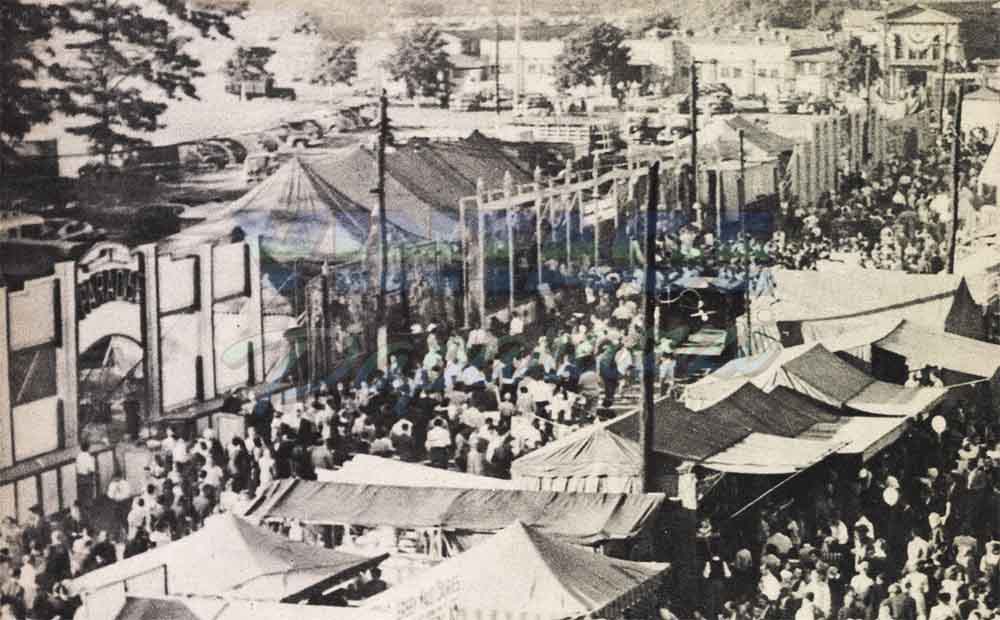

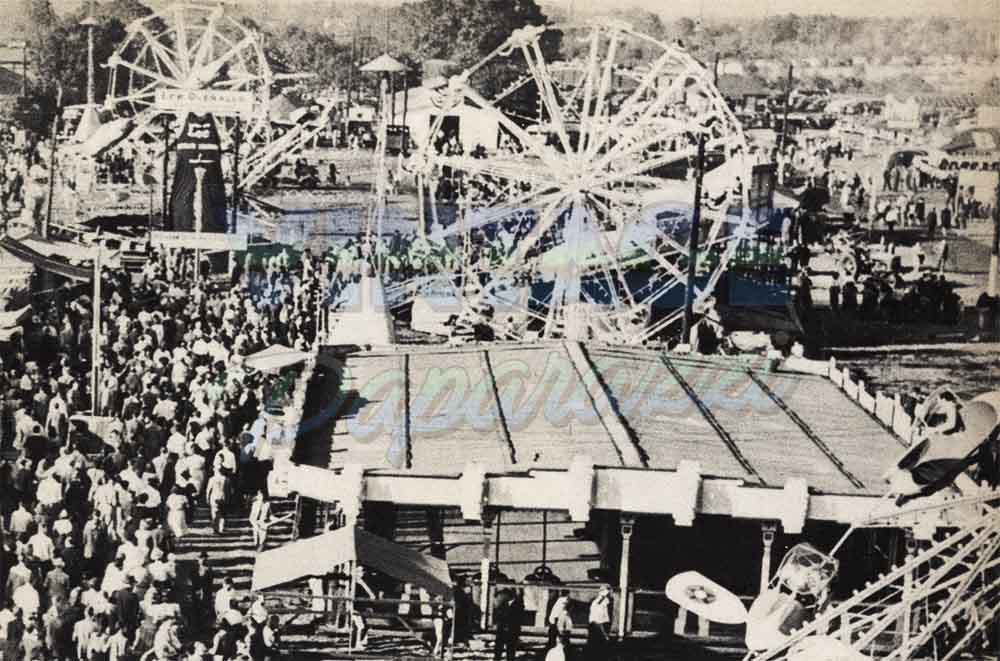

The so-called “front end” or “games” section of the carnival is where most of the malarky goes on. Amid the noise and glittering color, the men who run the games concessions drop out their bait. And like fish, the suckers always bite.

There are two basic types of carnival games, percentage stores and G-joints. The “G” stands for gaff or gimmick. Either way the place operates (and some are “two-way stores,” only “slipping in the gaff” when business is slow) they have one thing in common: they can’t lose. Since they can’t, and somebody has to, that leaves the customer.

Take the Hoop-la, for example. The customer is given three hoops for a quarter. inside the booth are a number of wooden blocks covered with velvet, and the idea is to ring one of them with a hoop. Prizes range from portable radios to expensive sets of china.

While a quater seems a meager price to pay for such loot (and the impression is not accidental), considering that it is impossible to get the hoop over the block, it is approximately 25c too much. The gaff here is the the velvet-covered blocks are not solid, but consist of a number of wooden squares piled on top of each other. The carny gently nudges one of the middle slats out a little bit past the others — and nothing short of World War II will make that hoop settle to the bottom. When the operator decides to show how easy it is to win, a subtle flick of his wrist squares up the block, and the hoop drops smoothly over.

In a variation of the hoop-toss, live ducks swimming about in a tank of water provide the target. The gaff in this one is more subtle, and it’s provided gratis by Mother Nature. It is simply the fact that ducks aren’t so dumb that they’re going to allow themselves to be hooped without a quack. They quickly learn that when a person with a hoop in his hand draws back that hand, the hoop will momentarily be winging their way. As soon as a hand goes back, they dip their quackers, and the hoop sails harmlessly into the backdrop. The operator proves it can be done by feinting first, which causes the ducks to duck, then throwing the hoop before the duck can nod his neck again.

Another variation of the hoop-toss is the clothespin joint. Here the targets are outsized clothespins clamped to a thick rope and bearing numbers, some of which correspond to a list of winning numbers displayed on the front of the booth. It’s no trick to loop a winning clothespin; the trick here is to collect your prize after you’ve won!

The operator has carefully selected the winning numbers so that, turned upside down, they read differently. Thus if a person loops a number 18, for example, the operator deftly turns the clothespin so that it becomes 81. It’s a pretty bare-faced racket, and needless to say, only big bruisers work the clothespin joint!

Pitching coins — any denomination up to a quarter — is another apparent game of skill that has a subtle gimmick built in. The idea is to toss the coin onto any one of a number of wide, flat pedestals and walk off with a ten-dollar teddy bear. “Nothin’ to it,” says the operator, as he tosses three or four coins onto the smooth surface. But no one else can make them stick, mainly because no one else had a drop of rubber cement on the bottom of their coins. If anyone gets suspicious and demands to see the operator’s coins, a quick rub of the thumb destroys all evidence.

That, in fact, is one essential of a good gaff: that it can be ungaffed at a moment’s notice to prevent the operator from getting his head bashed in by a disgruntled customer.

Almost every game on the midway has some degree of skulduggery to it. The Cupcake Rolldown seems easy enough on the surface. All you have to do to win is get the ball into the cupcake tin that matches the winning color. Upon closer examination, however, it turns out that there are not five colors, as you thought, but about fifty different shades, making the odds against winning enormous.

Shooting galleries that offer prizes for marksmanship are also invariably gaffed. Altering the gunsights just a fraction can throw most people’s air off, and the snipers who learn to compensate for this can be thrown into a tizzy by a slight nick in the bullet or BB. The feathers on arrows are doctored in the same manner.

A Steady Pace

A popular game af many carnivals is the Rabbit Race. A number of stuffed rabbits are placed on in dividual treadmills, and the person who can crank his rabbit up the incline to the finish line first wins the prize. If you crank too slow the others will pull ahead, and if you crank too fast your rabbit will start slipping. The key to winning, of course, is to ignore the other rabbits, and just crank away at a steady pace.

Even knowing the trick, however, doesn’t assure you a pile of prizes. If you start to win too often the owner will throw in the gaff subtly, and secretly, lessening the tension on your belt so that you can’t possibly win.

In his book Monster Midway William Lindsay Gresham says, “There are people who have an uncanny knack for beating ‘games of skill’ and often a joint will run on percentage until one of these rare birds comes along and threatens to clean out all the prizes. Then he gets the gaff ‘to protect the stock.’ ”

Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the high-striker, where would-be Sampsons try to win cigars and impress their girlfriends. Usually these are on the up and up, the trick not being so much strength as hitting the striker at the right angle to send the weight whistling up the wire to the bell. But sometimes someone who knows the knack starts winning one cigar after another, and though the operator can’t lose since he’s charging a dime and giving away a nickle cigar, he might throw in the gaff here by lessening the tension in the taut wire. The weight will vibrate going up and never reach the top.

One of the few games that are not gaffed are the straight shooting galleries — that is, those which are operated purely for fun and do not give away prizes. But you’ve still got to keep alert, for these places operate the universal gaff of carnivals the world over: the shortchange.

While shortchanging takes many forms, one of the most clever, in the hands of a smooth-talking operator, is the quarter count. It requires no sleight of hand, and it works this way:

You ask the operator for change of a five dollar bill. He takes out a handful of quarters and began to count them into your hand. “One, two, three, four . . . one dollar.”

A pause here, then: “A dollar twenty-five, dollar fifty, dollar seventy-five . . . two dollars.”

Another pause, then: “One, two, three, four . . .”

Placing emphasis on the word “four,” the carny breaks off and reaches into his pocket for more quarters. He continues: “Four twenty-five, four fifty, four seventy-five, five dollars.”

It has fooled many brilliant men. And if someone should count his change, the operator just reaches into his pocket, pulls out a bill, and says, “I’ll have to give you a bill for the last one.”

It should be clear by now that if you don’t keep your eyes wide open and preferably aimed at your wallet, you’re definitely going to get clipped at the fair. As Gresham says in his book, “One of the basic facts of carnival life is this: when any alluring bait is deliberately dangled in front of your nose, it has a hook on it.”

Give that some thought before you chomp off a mouthful next time!

It is a quote. Inside Story MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962