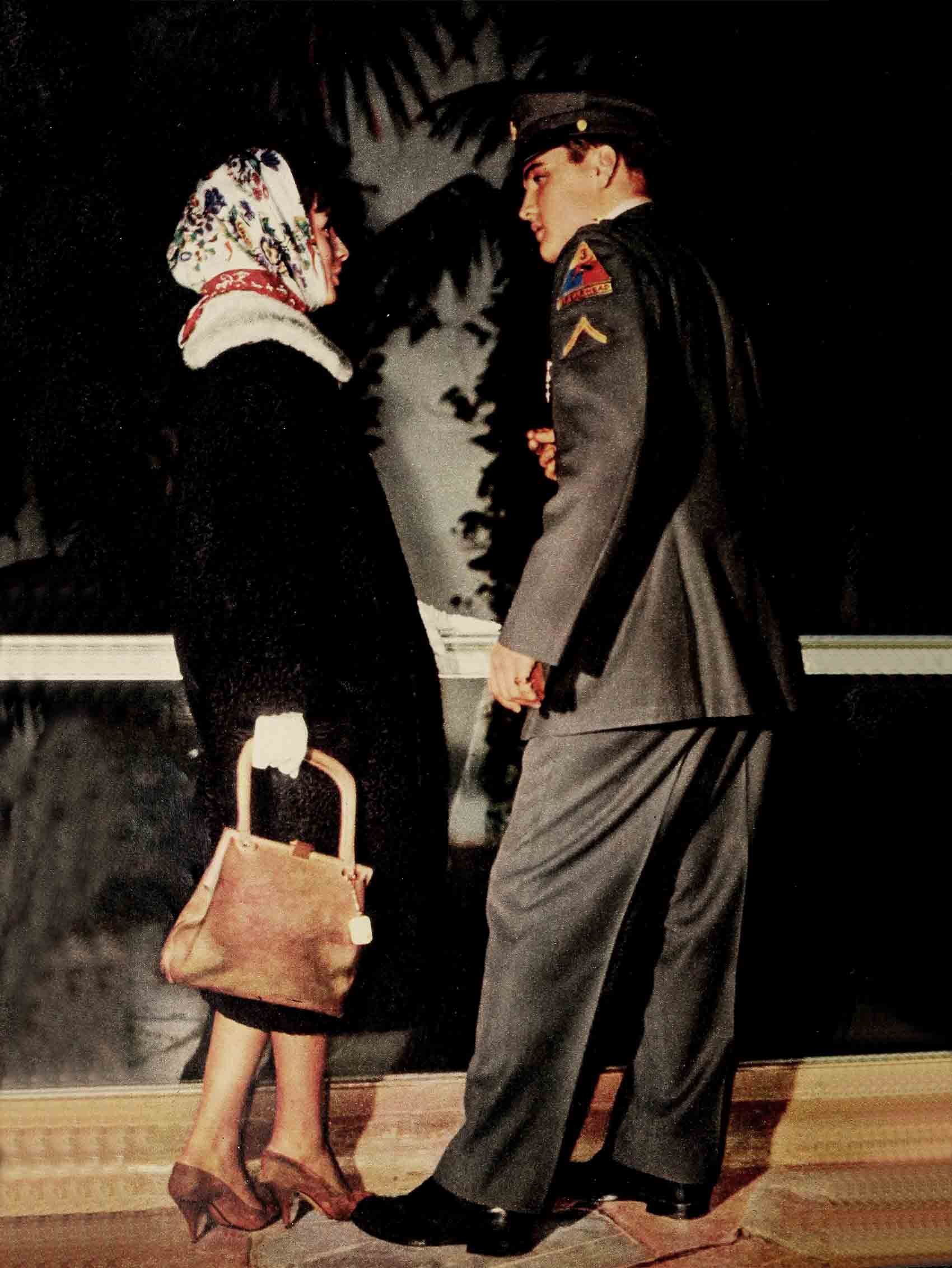

For Us There Is No Tomorrow—Elvis Presley & Vera Tchechowa

“All right,” “ Elvis Presley said. “I have something to tell you now.”

The reporter looked up, startled, from his notes. He had asked, as every reporter always asks El these days, how many cute fräulein he was dating at the moment. According to last reports ten, maybe twelve. And he expected, as always, that Elvis would grin, hand out a couple of additional names, and tell him he was having the time of his life, he’d never had it so good.

Only, suddenly, everything was different. The grin was gone from Elvis’ face. His eyes were serious. And there was a new note in his voice.

“All these—these “romantic adventures of mine,” he began slowly. . . He paused. He took a deep breath, “They’re not true,” Elvis Presley said. “I have one German girl friend. Only one. ‘Her name is Vera Tchechowa.” The dark, serious eyes looked straight at the reporter. “I think it’s time I told somebody that. Vera is—the only one.”

Fifteen minutes later he walked slowly out of the building, Private First Class Elvis Presley, United States Army. Tall and erect in his uniform, he walked down the Frankfort street to the corner where a white BMW car waited. The girl behind the wheel slid over as Elvis opened the door. For a long moment she waited while he sat, hands gripping the wheel, head bent, eyes looking—no-where.

“Did you tell them?” she said finally, her soft voice hardly breaking the silence.

Elvis nodded. “I told them,” he said. “I told them you were the only one. I told them I see you whenever I can. I told them that we understand each other, that we are friends.

“I told them,” Elvis said slowly, “you’re my girl.”

“Thank you,” she said gently. In the cold German afternoon, she waited quietly while the motor caught and roared, and the car moved smoothly away from the curb.

He had told them she was his girl.

Forever and ever, at least she would have that. . . .

They had met only months before. It was a strange meeting, an unlikely one—he the famous American singer, always a little different from the other GI’s no matter how hard he tried to be like them; she an anonymous little girl from Munich, trying wistfully to make a living as an actress. An unlikely pair—but still, at a Munich party, someone introduced them and hurried off, and they found themselves alone for a moment, staring at each other. She could still remember it because of what she had thought then: So this is Elvis Presley, the American singer, playing at being a soldier. The one who told everyone when he got here that he wanted- to meet German girls because “I’ve heard a lot of rumors about them.” Someone asked him what rumors and he grinned and said, “I’d better not answer that question.” Cocky, she had thought, arrogant. Expecting us to fall at his feet. Well, not me, Mr. Presley, sir. . . .

And then he had smiled at her.

“Do you speak English?” he asked, speaking very slowly. “I don’t know much German.”

He sounded almost—almost apologetic. But she kept her guard up. “Why don’t you learn?” she asked, her English careful and accurate, and very cold.

“I’ll tell you,” he said. “I never was very good at languages. The grin widened, and deliberately he broadened his drawl. “Some folks back home say Ah don’t even do so well with mah own.”

And she found herself, suddenly, laughing. Partly because he was funny. And partly because of relief. He was nice after all, and she was glad. It was against her nature to dislike people, even strangers, to feel that little cold hardness around her heart, to hear herself being cool and sarcastic. Because actually she was a very gentle girl, Vera Tchechowa—gentle, even a little shy. So she laughed and sat down with him to talk a while, and later when someone across the room called to him, she held out her hand to say good-bye.

To her surprise, he didn’t take it. Instead he looked at her oddly. “I’ll only be a minute. Would you wait for me?”

“I can’t,” she told him politely, “I’m sorry, but it’s time for me to get home.”

He had glanced outside. “It’s dark out,” he said. “You can’t go alone.”

Her eyes had followed his, out to the dark street below. “I’ll be all right.”

“I know you will,’ he said. “Because I’m taking you.”

He found her coat, he waited while she twisted a scarf around her head and neck. “But you can’t go with me,” she protested. “The party’s for you.”

He had shrugged into his overcoat. “The party’ll keep . . .” He smiled down at her. “You sounded kind of snippy back there for a while,” he said. “But I get the feeling—you need to be taken care of.”

And as simply as that, they had gone.

What happened on that long, moonlit walk through the Munich streets that night? Neither of them knew. . . .

How love comes about

But the next morning when the telephone rang she knew it would be Elvis.

“Vera, my pass is up, I have to get back to Bad Nauheim. But—I’ll have some time off next week end. Not much, just a little. I thought—if you could come to Frankfurt for the week end—I could see you there.”

He paused. She said nothing, holding onto the phone, wondering.

“I know it’s a lot to ask,” he said. “I know well-brought-up German girls don’t go away like that. But you could stay with friends of mine, a married couple. Or you could bring someone—your mother, anybody. I wouldn’t want to hurt your reputation or anything. I’d come here if I could, if there were time. But there isn’t. And—I want to see you—so much.”

She felt her heart turn over. The cocky American millionaire, she thought. This lonely boy . . . “I will come,” she said softly, into the phone.

Who knows how love comes about? On those week ends in Frankfurt—for there were more than one—they discovered each other slowly, and almost always with delighted surprise. She found him intelligent, eager to learn, wanting to know about her childhood, her feeling for her country. He found her honest, shy, frightened of the crowds that haunted his hotel for a glimpse of him. “Why?” he asked her when she insisted on meeting him only alone, away from the reporters and the autograph hunters. “You’re an actress—publicity is good for actresses.”

She raised her head proudly. “Not if they can act.”

He had laughed. “A lot of people would disagree with you, honey. Publicity never did me any harm. . . .”

“That’s different,” she said eagerly. “Yours was publicity just for you, for what you are. But for me to be famous for going out with you—that is different.” Her eyes were serious. “Someday I will be very good on the stage. And I do not want people saying I achieved success because for a while I dated a famous American.”

He had never seen her so in earnest. “And after you get famous on your own,” he said gently, “are you going to run away from the cameras then, too?”

She nodded, still serious. “I don’t like that sort of thing. It makes me uncomfortable, nervous. A crowd in the theater—yes. A crowd in the street, chasing after you—I will always run from that.”

Love and fear grew together

So they met, for her sake, in quiet, out-of-the-way places—in small restaurants; at the zoo where children gaped at animals, not celebrities; in the home of his sergeant where they played with the babies of the family, and served as sitters now and then.

And love grew.

And with it, fear. Fear for the future. Fear for the unasked questions, the subjects they never discussed.

For with all the ways in which they were wonderfully alike, there were so many in which they were different. He loved the glamour of his life, the excitement—she remembered wistfully the quiet countryside where she had grown up, the tiny village where everyone knew everyone, where life went on, unchanging, from year to year. And there were the other, subtle, differences that came because he was American, she was German, had been born to a different culture, had known war and trouble in different ways, had received different educations, had different ideals.

One Sunday night, driving her to the Bahnhoff in time for the train to Munich, he said: “You know, I’ve got to tell them something, Vera.”

Contented, curled in the corner of her seat, Vera had stretched a little. “Tell what to whom?”

“Well, it’s the reporters, honey. You know—they keep asking me who am I seeing, what am I doing, who do I date—well, you never wanted me to mention you, so I don’t. But I’ve got to give them something to write—they’ve been good to me a long time and they need news.”

Vera shrugged. “Tell them a lie. It’s all lies they print, anyhow. I read once how you drive like a madman always. When I myself know you drive like a saint, so careful.”

Elvis grinned. “When I’m with you, I drive like a saint. When I’m not . . . well, anyway, they only print lies when nobody tells them the truth. Soon, if I don’t give them something to write, they’ll be saying I’m secretly married. Then they’ll hunt you down, take your picture, follow you around—” The grin grew wicked. “How will you like that?”

“I won’t,” she said.

For a long moment she was silent. Then, slowly. “Elvis,” she said, “I watched you one day, you know? You were late to meet me, so I walked over to your hotel, and I stood outside, across the street. I was there when you came out, into the crowd. I saw how they greeted you, with shouting and waving. And I saw your face, how you looked at them.”

Elvis guided the car through the narrow, cobblestone street. “Yes?”

Give it up while it’s still good

“I saw the love in your eyes,” she said. “I saw how you came alive, how you waved to them and signed the books. I saw how you loved them. You could not live without them, the crowds, the shouting.”

Elvis stared ahead of him, down the street. “No,” he said slowly, “I couldn’t.”

“And I,” the girl said softly, “I could not live with them.”

They sat in silence. Then, casually, Vera said, “You know, I had many friends who were married to Americans.”

“And—?”

“Oh, they would write home how difficult it was to make the change, to adjust to a different country, different life, different language. It must be hard, don’t you think, to have your own children grow up to speak another tongue, in a world so different from your own.” She took a deep breath. “And then too I read about Hollywood. How even the best marriages are in trouble there. That is true, is it not?”

“Sometimes,” Elvis said. “But—”

“Oh, there are so many ways,” Vera said, “in which love is made to die, even when all things are right. But when many things are wrong—like a different country, a different life, all that—then sometimes I think it is better if people give up love while it is still good, and not kill it in misery. Anyway,” she said, very lightly, “that is what I think some of my friends should perhaps have done.”

Simple words. a casual conversation. And yet, in the long silence that fell between them, they knew that the questions had been answered, finally and forever.

And the answer was—no.

In her corner of the car, the girl sat staring out the window. Without turning her head she said: “I think perhaps you should take other girls out. Then you can tell the newsmen about them.”

“I don’t want to take other girls out.”

She turned to look at him. “And I don’t really want you to. Do you think I will not be jealous when I read about you and them? I will—I will probably tear the papers to shreds and jump on them. But it will be better for both of us. I will have my privacy and I will see you week ends. You will have news to tell, and something to do on week nights.”

“Is that all?” he said.

“Of course. What more could there be?”

“I don’t know,” Elvis said.

But both of them knew. It would be also a preparation, a step toward the day ahead when he would go home to the life he could not live without—the life she could not live.

It would be the beginning of good-bye.

At her train, he lifted her suitcase to a rack and stood in the compartment door. “About these dates I’m going to have,” he said, looking down at her. “Read the stories carefully, you hear? Maybe they won’t make you jealous after all. . . .”

Within a month, she knew what he had meant. For the papers were suddenly full of Elvis and his dates, Elvis and his girls. On one front page after another, he was kissing them or being kissed by them, with that look of roguish glee on his face. And who were these girls. . . ?

They were fifteen-year-old, pony-tailed American high school girls, five years too young: for him. They were awe-stricken, blonde-banged German girls, who confessed in confusion that they spoke scarcely ten words of English. “Why sure,” Elvis would beam, “we have a great old time. She brings along a dictionary and we manage to talk a little. Sometimes we go to a movie—only depending on which language it’s in, one of us doesn’t dig it much.” “And what do you do after the movie?” the reporters would ask, pencils poised. Elvis would shake his head. “Well, thing is, she’s got to be home by eleven and I have to be at the base early, so mostly I put her in a cab. . . .”

Elvis dead!

No, she would not be jealous. She would not feel, as she thought she might, the tightness around her heart at the sight of his name coupled with someone else’s. They had each other for now. The future did not matter. The secrecy did not matter. If he were just anybody, how proud she would be to tell her friends, to boast of him. But as it was, it was enough that she knew, that her heart knew.

Until the day she turned on the radio and heard that he was dead.

“GI Elvis Presley,” the announcer’s voice proclaimed, “died today in an automobile accident in Frankfurt. Private Presley, on duty in Germany since—”

“No,” she whispered. “No. Please, no—”

Hours later, the phone rang. She picked it up and an anxious voice said, “Vera? It’s me, honey, Elvis. I called as soon as I heard about that rumor—I was scared you might have heard it, too—”

“It’s all right,’ her voice said slowly, deadened. “I did hear it, but later, I heard it was not true. They said so on the radio.” Softly, she began to cry. “I was so—so afraid.”

“It’s all right now,” Elvis said. “Don’t cry, honey. Listen, I’m fine. I’m having a beer. It tastes great when you’ve been dead a while.”

He waited for her to laugh. Instead he had to strain to hear her at all.

“Elvis—I—I must talk to you. I have changed my mind. About being so—secret. I thought it didn’t matter that no one knew, but it does matter. What if you had really been hurt, what if—”

“Honey,” he said, “talk slower. And don’t cry. I can’t understand you.”

“I’ll try,” she said. She took a deep breath. “You see, this way—I have no—no claim on you. If you were to be hurt, no one would think to call me, no one would know I would care. If you had died—I sat here and all I could think was, what if they won’t let me come to the funeral to say good-bye? What if you needed me and nobody told me? I was wrong, Elvis. If it isn’t too late—if you still want to—then I would like you to tell them. . . .”

And so on that cool spring afternoon. he told the reporters the truth. That he had one girl in Germany and only one, that her name was Vera, that she was his girl. He did not tell them the rest, the things that were too deep for words—that they loved each other but they would not marry, that they were too different to live together, that each had a world the other could not share. He did not tell them that their love was the kind that knows when it must end, that cares more for the happiness of the other than for itself. He did not say that they would give each other up when the time came with their love still intact, still fresh, still beautiful. He did not say what a special girl he had, that most women ask for something from a man—jewels, or wedding rings, or at the least, promises—but that his girl was different indeed, for she asked nothing of him, nothing of the future.

She asked for only one thing.

A little thing.

A memory.

“She is my girl,” he had told the reporter, told it for all the world to hear, for her heart to treasure.

When the time came, as it would come, to say good-bye—she would still have that.

THE END

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MAY 1959