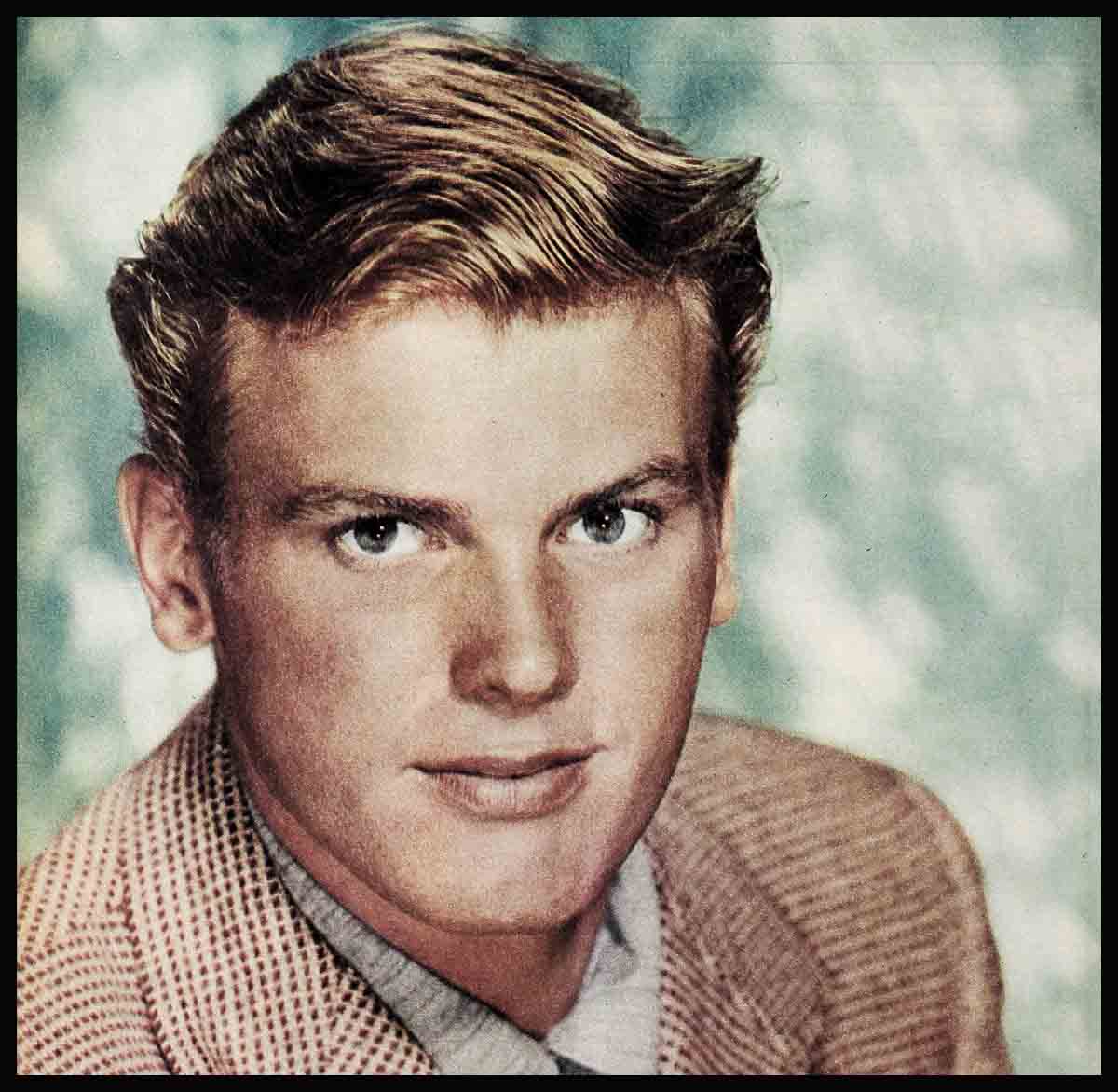

Tab Hunter-And They Call Him Dreamboat!

The hurdle at the riding academy was high. It was also a little dangerous if you didn’t have the coordination and skill it took to jump a horse over it. But the blond kid, sitting his horse like a professional equestrian, would have been any horseman’s equal as he collected his mount and took him over. I had to admire the skill with which he lifted his weight from the animal at the proper moment and helped the horse jump, and the courage this kid displayed in trying it.

I’m the kind of guy who likes to tell people when I think they’ve done something to be congratulated about, so I rode up to him.

He gave me a quick shy smile of thanks and a nod of appreciation toward the horse I was riding. We started to talk horses.

I was an actor at the time, serving my hitch in the Navy. He was a blond twelve-year-old. Just a kid. But there was a certain poised certainty about the way he moved, the way he discussed horses that made you forget how young he was.

The career I was involved in happened to come up in the conversation and I remarked, “With your looks, kid, you ought to make a try for the movies yourself.”

He dipped his head sort of shyly, mumbled a little and said, “I wouldn’t want to wear all that make-up on my face and bother about learning lines. I’d rather ride.”

And he meant it. Horses were his life, and he was willing to do anything to ride the best.

Shortly after I met him he wanted to work out a certain jumper. The owner agreed if Tab would pay half of the feed bill. Naturally the kid couldn’t afford it. It was heartbreaking to watch the yellow-haired adolescent looking after the big horse he wanted to ride so badly. Navy pay didn’t give me much spare cash or I’d have paid the bill myself. As it was, Tab’s mother agreed to share the expense with him if he could earn part of the money. So he took a job at the orange-juice stand on Hollywood Boulevard to get the funds.

That was the first time I’d seen the determination to achieve whatever his heart was set upon. I’ve seen it a lot since then. Tab has always worked hard until he became a perfectionist in whatever struck his lasting interest.

He learned to become one of the best junior horsemen on the West Coast. After he’d won a bunch of blue ribbons, he lost the drive temporarily and turned whole-heartedly toward the silver blades of amateur ice skating competition.

At once, as soon as the fancy had taken him, Tab plunged into extensive practice. He spent countless hours at the local ice rink, repeating basic figures, polishing techniques, practicing, improving his form and style. Along with the actual repetition of skating, he grabbed up chunks of theory and some goals to shoot for. Whenever Ice Capades hit town, he was at every performance. Donna Atwood and Bobby Specth, charmed by the youngster’s eagerness to learn, would spend hours talking to him about when they too were competitors in the sport.

It wasn’t long before he felt he was good enough to take a stab at competition. He entered and won quite a few amateur championship awards. Tab is still an amateur and plans someday to get his gold medal.

I had come back from the Navy and was working in “Our Very Own” when Tab came into Los Angeles and visited me on the set one day. That evening he even went so far as to admit, “You know, Dick, maybe pictures aren’t so bad after all.” I had a feeling it would be the start of something. Even that much interest, expressed aloud, meant he’d been thinking about it. Later, I learned he had joined the dramatic group at St. John’s Military Academy and had a few parts. He was temporarily sidetracked when he decided to join the Coast Guard.

I didn’t see much of Tab in the ensuing months. I went to New York on business. Tab, who was in boot camp in Connecticut, became a frequent visitor, calling on me when he got leave. I took him to his first Broadway play and saw right then the rekindled spark of interest in acting.

The New York interlude was a lot of fun for the kid. I had a small apartment which I told him he could use whenever I was out of town. Upon my return from a weekend trip I usually found that he’d been on liberty with a half a dozen of his Coast Guard buddies—the cupboard was always bare. They were never fed at camp—if the way they cleaned me out was any indication.

I got a kick out of seeing Tab put all three of his big interests into practice at the same time. There was horseback riding in Central Park, ice skating in Rockefeller Center and shows at night along Broadway.

At three thirty one morning I came home from a party to find Tab forlornly sitting in the big chair.

“Hiya buddy,” I said. “Thought you were due back at the base this evening.”

Tab looked kind of sad. “Yeah.”

“Get goin’ boy or you’ll be sitting out restriction.”

“Well, you see, it’s like this, Dick. This gal and I went to a show and to dinner and well. . . .”

He didn’t have to say any more. The combination of being generous to a fault and not having the vaguest idea of how to handle money spelled out “broke.”

“That’s right,” frowned Tab, “I blew the roll and I was as far as Grand Central Station before I realized I hadn’t the fare.”

Lending Tab the few bucks to make the fare was no problem. What did present difficulties was the fact that the last train for the evening had already pulled out and there wasn’t another scheduled for several hours. And that one didn’t get him back to the base before roll call.

Now the punch line of the story should be that Tab was late, got thrown into the brig or at least given company punishment and thereafter became as money-conscious as old Midas.

No such thing. A buddy covered up for him, as buddies in service often do, no one knew he was missing and Tab is as careless about the state of his bankroll as ever.

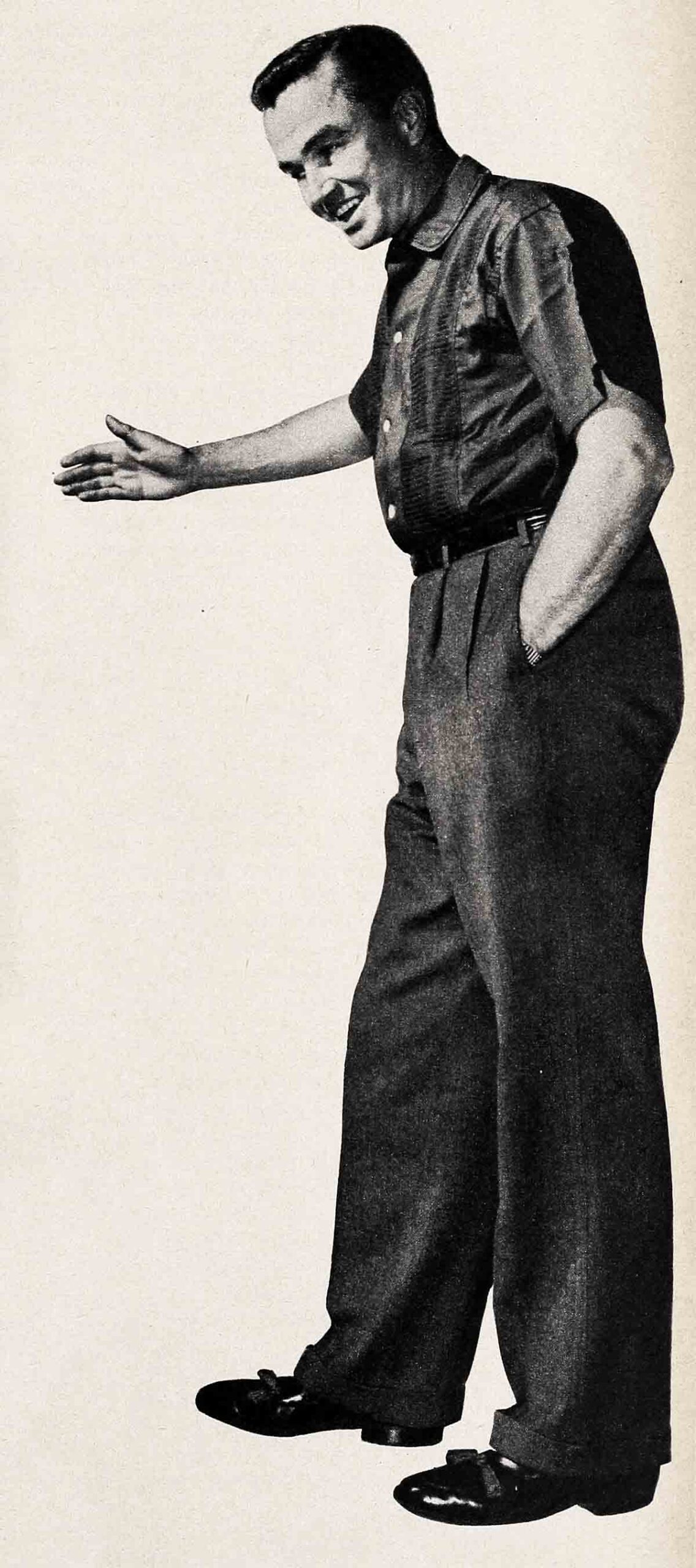

When Tab finally left the service he came directly to Hollywood and looked me up, for by this time I’d returned to the Coast and was in the midst of a transition from actor to agent.

“Dick,” he said, “I feel now that I honestly want to try for a career in pictures. Do you think I could?”

“I said it when you were a twelve-year-old kid, Tab, and I say it again. In fact, you have more to offer now. I don’t see how you can miss.”

He hit it with all fours in the same sincere, hard-driving way he’d done things all his life and results showed. He had it.

But it wasn’t as easy as some people might think. Tab did Little Theatre work and knocked on studio doors for nearly two years before the big break came.

Paul Guilfoyal, whom he’d met at the rehearsal of a play, thought of Tab and suggested him for the role of the sexy young giant in “Island of Desire.”

He was tested, signed for the picture and given a name-change from his own Arthur Gelien. Tab said at the time that he didn’t like the new one much but that, after all, a name is only as important as the owner makes it.

He proved it by getting the role in “Island of Desire” and following it with top honors for himself in Photoplay’s “Choose Your Star” poll in 1952.

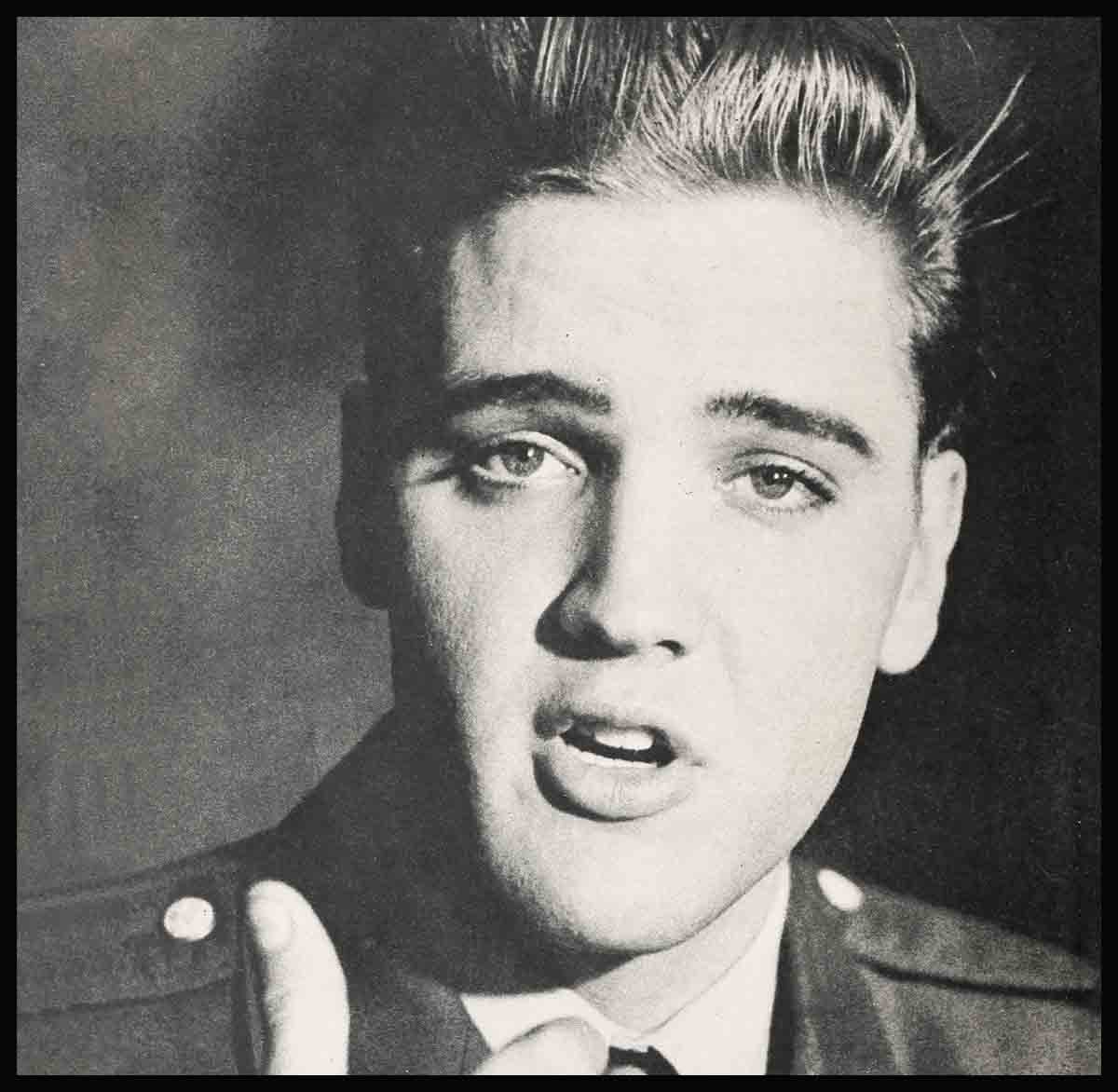

Then, one after the other, came roles in “Gun Belt,” “Steel Lady,” and “Return to Treasure Island.” And now he has a co-starring part in “Battle Cry.”

In any friendship certain things pop into mind that are out of any sort of sequence or chronology. Things that impress me about Tab. Things that are perhaps the truest index to the kind of a guy he is.

For instance, he won’t simply run into a shop and take the first thing at hand when he buys a greeting card or a gift. He goes out of his way, takes his time, exercises his taste, his sense of humor and displays a real intent to please someone. Debbie Reynold’s last birthday found Tab on location in San Diego. Instead of horsing around with some of the other guys in the cast down Tiajuana way at night spots, Tab spent hours searching for something appropriate. He finally found just what he’d been looking for. Something he knew would please Debbie. It was a special kind of hand-carved bank shaped as a bull. He had her name engraved on it and presented it to her along with a big bottle of her favorite perfume.

Tab’s own fine taste in clothes recalls another act of generosity. When I’m ready to buy some additions to my wardrobe he often comes along to heckle and to help in the selection. On one occasion a corduroy jacket caught my eye and my fancy, but the price caught me with a thin wallet. I couldn’t afford it, so I forgot it, but when my next birthday rolled around, Tab showed up early with the selfsame coat under his arm.

A lot of what Tab is, of what he’s been able to make of himself can be credited to the hands and heart of his mother. Kind and understanding, Mrs. Gelien, whose only other son, Walter, is married and living near San Francisco, unselfishly helped Tab to decide to go out on his own.

After dinner one night she said, “Tab, you’re twenty-one now. I love you and I want you to be near me but I think, for your own sake, for your development as an individual, you should be on your own.”

Tab had been thinking of such a move for sometime but felt he should remain at home. His mother sensed this and sensed the rightness of the time. Tab left and found a place close enough so that they could see each other often.

Mrs. Gelien’s wisdom paid off for her son in helping him achieve added poise, confidence, a fresher, more mature attitude toward people and things.

In Tab’s growing years he used to be extremely shy around girls and older people, an ailment common to most growing kids. With his new independence and the broadening influences of his trip to Europe, Tab has emerged as a man able to meet the demands of social activities necessary to an actor. Now, at a party, Tab holds his own, can make small talk or seriously discuss practically any subject. Girls like Debbie, Lori Nelson and Terry Moore, who’ve always liked Tab but were reserved in their opinion of him, now admit they thought he had too much kiddish exuberence about him before, that now it’s tempered with maturity.

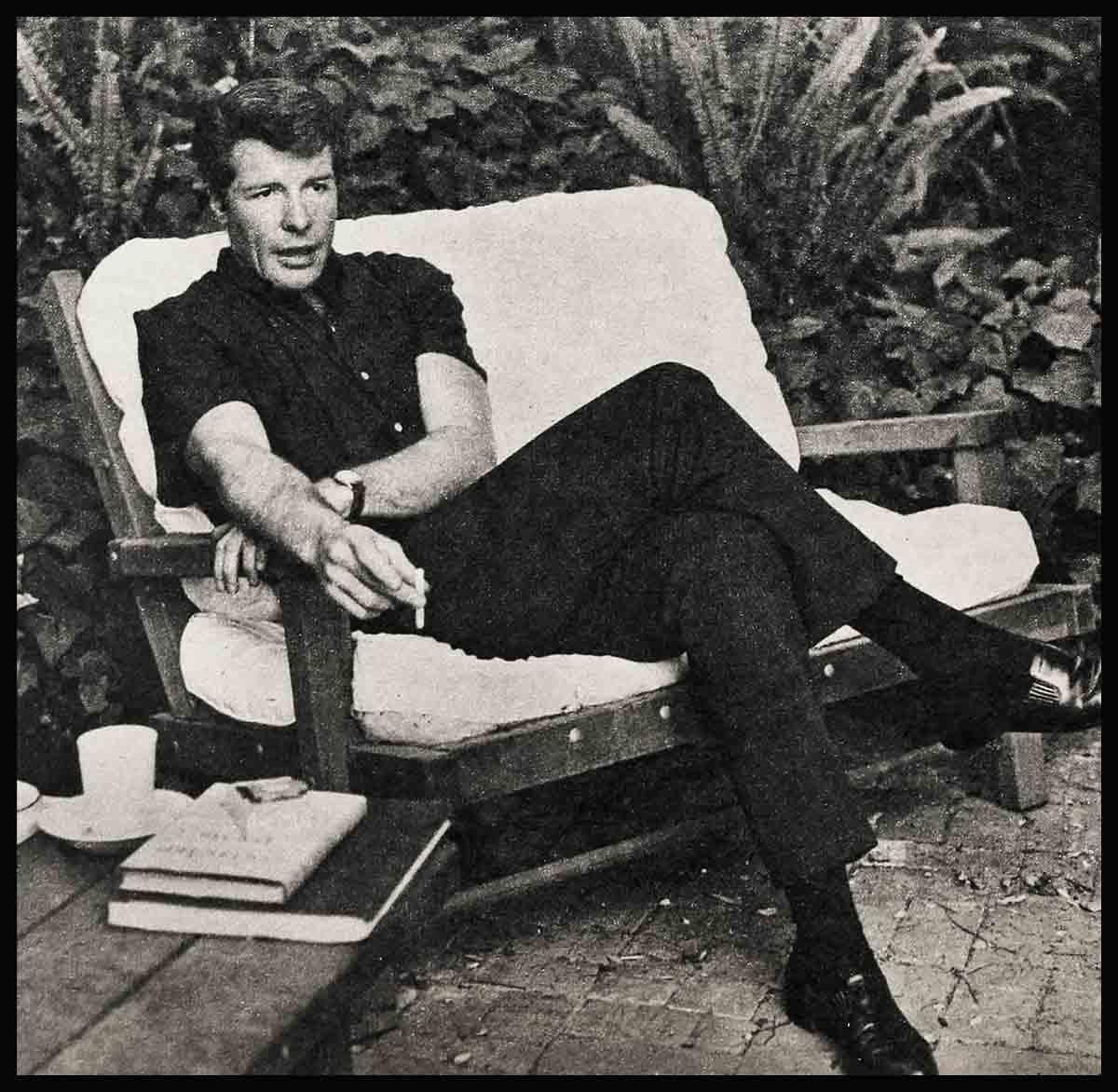

As his advisor, Tab and I necessarily see a lot of each other. But beyond the business relationships, as friends of long standing, we enjoy each other’s company. Occasionally we double date, but more often, when we both feel like a quiet evening, he’ll drop over to my place for a game of poker or scrabble or just a long talk about careers, gals and things.

I don’t want to give the impression that Tab is Mr. Perfection or a Sir Galahad. He has his failings, plenty of them, but he has a certain charm even in error that prevents anyone from getting really angry with him.

I can work up a pretty good bug on the business of money. Time and again I’ve said, “Tab, you must begin to save your money. You’re a star but you’re also a free-lance actor. You may do five pictures in a row, then all of a sudden a dry period can set in. No pictures. No income for a while. There has to be a reserve to fall back on. It happens to the biggest stars so use the old Boy Scout motto and be prepared. Save some of it.”

Tab will look at me, nodding at the proper places, acting very conscientious and determined to start salting it away.

“You’re right, Dick,” he’ll say. The next day he’ll spot a sport jacket he likes. He’ll buy it. A little later it’s a cashmere sweater. He’ll show them to me all smiles and I’ll blow my top.

Then the explanations begin. “A bargain. Got to have this for the party tomorrow night.” This, that or the other thing and the first thing I know, I’m at the same shop getting fitted for a jacket or sweater I can’t afford any more than Tab could.

Then, too, he’s got a share of “ham” in him. It seems to be an occupational disease with actors. (I had it myself.)

At the House in Palm Desert, Tab, who had never seen a can of paint from the business end before, pitched in and was splashing color around, sawing boards, hammering nails and topped it off by making a cornerstone in cement engraved with the inscription “God’s Little Acre—Dick Clayton.” Then he put “Tab” in the upper corner—just couldn’t resist top billing. He got such a kick out of the gimmick, though, that I couldn’t object to the little hunk of up-staging.

Tab’s not afraid of manual labor, but on the house project he had a tendency to overrate how much sweat and strain he actually put into it.

“I’ve been working like the devil,” he’d say to anyone who’d listen.

“That Clayton is a real slave driver.”

The truth was that he did work hard and do what he was told, but whenever there was a break, I’d grab a snapshot of Tab asleep in the wheelbarrow or grabbing forty winks the other side of the wall. Then when I heard him boasting, out came the snapshots.

A star’s adviser is sort of father, brother friend, confidant, mentor, slave driver, wailing wall, lawyer, financier and policeman. On top of that, Tab and I have a real friendship. Sometimes I think he takes advantage of the friendship part and forgets I too have an active interest in his career. That’s when I have to come down hard. If he tries to jolly his way out of an acting lesson or relax his training a bit, no matter what the reason for his lagging, I want to know why. Tab always seems a little surprised when I jump at these things.

Tab is a star, but he’s far from being a complete actor. He needs work, constant attention to detail, roles to work with and absolute concentration to secure the position he’s attained. It took years and years for even such idols as Taylor and Power to get to their positions of confidence and certain ability from which they aren’t likely to be shaken. I tell this to Tab every time he steps out of line and lets down more than he should.

He ducks his singing lessons sometimes. He’s got a good voice and I’ve told him he can’t tell when he might be called upon use it in a picture. But sometimes he’s lazy.

Again, I get a little ruffled when Tab falls for flattery a bit too much. It’s a natural human trait and the compliments have always been well meant, but when it happens, I have to turn Dutch uncle again. “It can be ruinous to your career. I’ve been through the ropes myself, and I know how easy it is to let other people’s kind words influence you to the point where you think you can sit back on your laurels. You can’t.”

Tab listens carefully and apparently understands that what I’m telling him is savvy and true. But a little too much air in the head and I have to be at him again.

“There are dozens of young guys who are ready, able and anxious to have your niche, and they’ll knock themselves out to get it. The bigger you get, the more people are gunning for you. And the more certain you have to be of what you really have.

“Look at me,” I set myself up as the horrible example. “It happened to me. Profit from my mistakes or you’ll end up being an agent.”

Tab smiles at that. “Okay, boss.”

With all the temporizing he learns.

One night I gave him a lecture about his not studying the characterization of a role enough. I thought he had a tendency to neglect thinking his part out thoroughly. He threw that one back at me graphically.

The day before he was to leave for location on Warners’ “Battle Cry,” Tab came over with a twenty-page manuscript. It was a complete character analysis of the role of Danny, the boy he was to play in the picture. From my knowledge of character delineation and motivation I thought it hit the part right on the nose, but I withheld opinion until I’d shown it to his coach to see if he’d had any help on it. The coach said “No” and was amazed.

Actually, and don’t tell him I said so, he’s improving plenty and coming along fine. Recently he got a little badly needed stage experience under his belt.

When the producers of “Our Town” approached Tab to play the lead of George Gibbs in the West Coast stage production of the Pulitzer Prize play, Tab phoned me and we discussed the pros and cons of accepting the role for hours. He realized the challenge, since he’d never been on the professional stage before. When he finally decided to do it, he put everything else aside and really concentrated. He worked hard and took the advice of his co-star Marilyn Erskine.

Tab will be the first to agree that he was lucky to be associated with this fine young actress who has been in the professional theatre since she was four. She generously gave of her time and talents to help Tab with his performance, and I know she felt rewarded when the critics acclaimed his work. I’m certain, too, that he was fully aware of her contribution to the acclaim.

Many people, knowing of my long association with Tab, ask me frankly if his success is perhaps more than he can handle.

Sudden exictement around any personality tends to bring up that poser. There are pressures, of course. He does get a bit carried away by the applause at times, but that, too, is part of being an actor.

As his adviser, I will say that Tab has the means to solidifying the success he’s garnered and firmly establishing himself in the acting profession.

As his friend, I can only point out that if he could handle a spirited jumper when he was twelve there’s no reason under the sun why he can’t handle a spirited career now.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954

vorbelutr ioperbir

4 Temmuz 2023Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was looking for!