The New Look In Hollywood Men

The current movie heroes are boys trying to do a man’s work. Most of them are adolescent, and this applies regardless of age. These heroes include boys who’d like to be men. Some play tough guys, like Paul Newman and Marlon Brando. Some are rebels like the late James Dean and the current Sal Mineo and Elvis Presley. Others, like Tony Perkins, shown on this page, play it shy and boyish. What’s wrong with this new look in Hollywood men? Why are the old, reliable favorites—Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Gary Cooper, John Wayne and company—still carrying the big box office burden and running away with the heroine at an age when they might well be settling down to pipe and slippers? Does the fault lie in the way these stars are being handled, or in the stars themselves? To each his own, and every generation has its own heroes. Let’s face it: The actor is never isolated from what is happening around him. The garish, giddy Twenties had sleek, smoldering Valentino. The grim depression Thirties had a two-fisted Cagney and Gable, realists in a rough world, while the smooth Melvyn Douglas and David Niven offered an escape to dreamed-of elegance and sophistication. World War II found the ideal hero of sterling strength and character in the rugged persons of John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart and Gregory Peck.

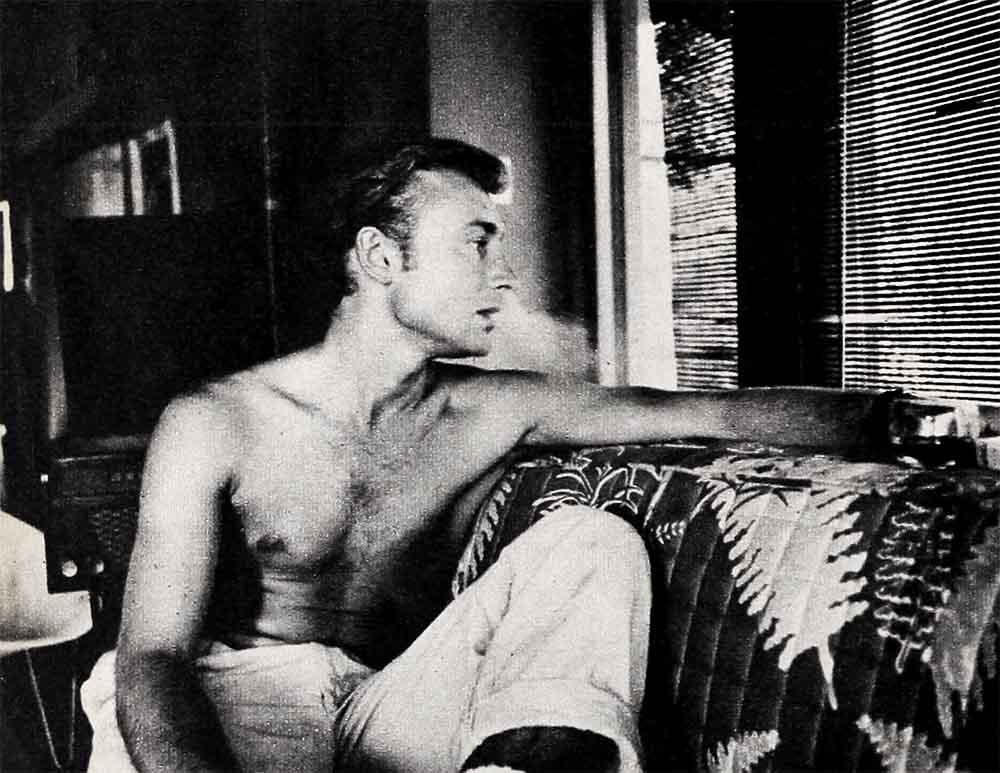

Then abruptly, during the early years of postwar confusion, a strange new movie idol appeared. Clad in T-shirt and blue jeans, serious, moody, an individualist to the core, Montgomery Clift was a far cry from any of the previous screen-hero styles. And in his wake, off the Broadway stage, mumbling, brooding, scratching, sexy and confused, came the first of the modern movie heroes—Marlon Brando.

Gable—The King—had been dethroned. But Brando, and the actors who followed in his footsteps, had no desire to be King. They knew in the 1950’s Kings have no power and are out of style.

These years belong to the rebels and the teen-agers. On waves of teen-agers’ adulation, Jimmy Dean became a cult and singing idols—Elvis Presley, Pat Boone, Tab Hunter, Tommy Sands—were carried to stardom. The surge of rebellion runs the gamut from young Sal Mineo to the disciples of the Actors Studio, such as Ben Gazzara and Tony Franciosa.

How did this strange state of affairs come about? Let me go back to the beginning, with Mr. Clift. Monty became a popular idol overnight. No ballyhoo, no buildup. Just one appearance in a more-than-good western called “Red River.” The only explanation for this was that Monty’s personality struck a “strong responsive chord in his audience.” And the audience? It was an audience just recovering from World War II, still sporting a colossal hangover of postwar readjustment, still groping. They had little use, with the war won, for the physical heroes, the Gables and Waynes. And here’s where Monty stepped in. Sensitive, intelligent, he refused to conform, to give up his T-shirt, blue jeans and cheap walk-up apartment. He struggled within. G.I.’s, returning civilians, found a symbol to identify themselves with and their wives and girlfriends found insight into their returning heroes’ problems. It was early 1950.

Then a guy named Brando struck the Broadway stage in “Streetcar Named Desire,” made a splash in Hollywood in “The Men.” Monty was eclipsed. True to his type, he couldn’t have cared less.

Clift had been the idol of a time of transition. Brando was the first of the modern movie heroes. A hero of a time suddenly dominated by Iron Curtains and the H-Bombs, of fear and rebellion.

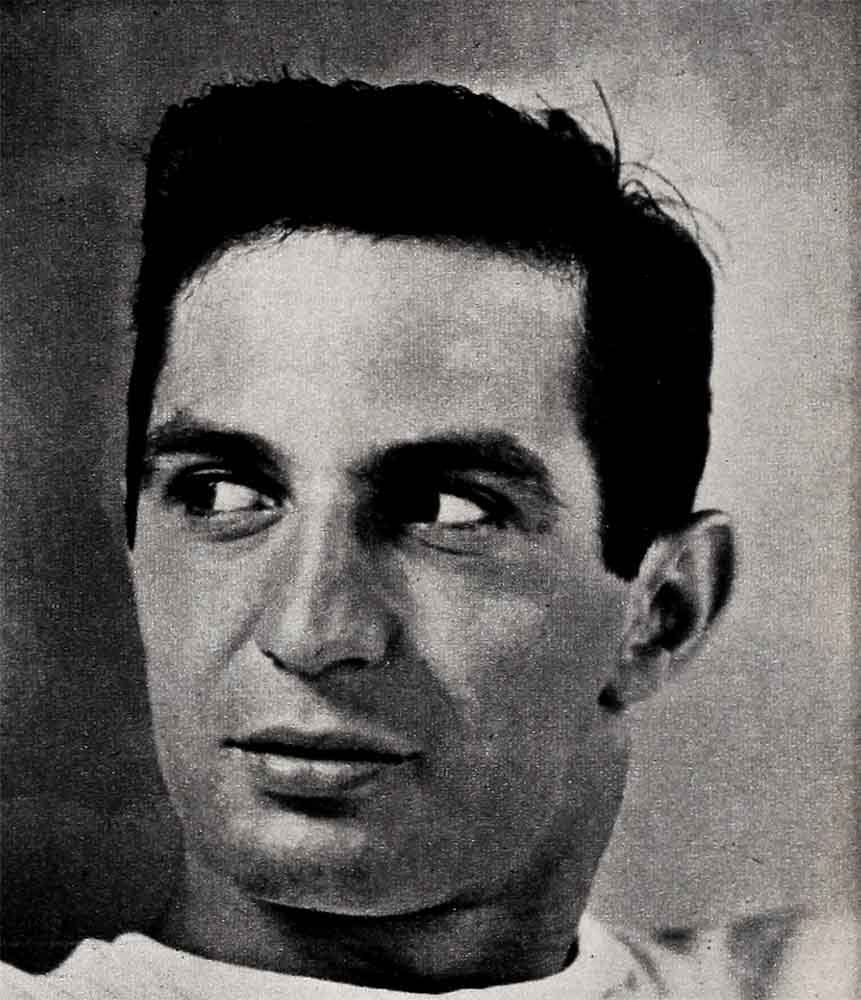

Let me return to Brando. It has been established that Marlon is a pioneer. He cleared the road for the others, from James Dean to Paul Newman, to Tony Perkins to James MacArthur, etc. While the pack was following, Brando grew up and matured. He visually went from T-shirt to a tuxedo. He is no longer the extreme nonconformist. He has joined the ranks of the business-actor and has his independent picture company, Pennebaker. Also, he asks in the neighborhood of $200,000 a picture, and from fifty to eighty percent of the profits. This is a very nice neighborhood for an actor. A different neighborhood from the underprivileged Stanley Kowalski and Terry Malloy. Brando has changed decidedly since then, but he produced a new model and they soon began coming off the assembly line—the Actors Studio actor. A moody, introspective type that was hardly calculated to set hearts fluttering.

Although not a regular student of Actors Studio, Brando pioneered its famed Method and set off the acting style copied by many of the current male crop. An explanation of The Method seems essential in understanding them, and the method of The Method is best explained by Actors Studio director Lee Strasberg: “I stress the difference between the actor who thinks acting is an imitation of life and the actor who feels acting is living. Unless the actor onstage really comes alive, really lives a character, he can’t give anything but a superficial interpretation. We deal with the actor’s inner life. Our emphasis is laid on thought, sensations, imagination, emotion. . . .”

Sounds like sense? What’s wrong with an actor exploring his inner self? Not much—within limits. But some Actors Studio graduates. to quote a quote, act like they just jumped up from the analyst’s couch. Women burdened with their own problems were not keen to fall for a hero with neuroses.

The next disciple of The Method to become a movie star was James Dean. In the beginning, before the legends set in and reality was forgotten, Dean performed a la Brando in various scenes of “East of Eden.” Many critics and audiences said so. This performance was to be expected. Jimmy had attended the Actors Studio; the film was directed by Elia Kazan. Gadge’s gadget is Actors Studio. Before the movies, Dean appeared on Broadway in two plays—“See The Jaguar,” and “The Immoralist.” The last-named won Jimmy the Donaldson and Perry acting awards. It is significant none of the alert New York drama critics commented that Dean was similar to Brando. The change which took place occurred on a sound stage.

Yet more than enough of Jimmy Dean emerged to overpower both the Brando and The Method influence. Jimmy was sensitive, poetic and an individual. The movie producers were soon looking for “another Jimmy Dean” as they continued their search for “another Marlon Brando.” The type was now firmly established. And while romance wasn’t exactly in bloom Jimmy made it possible to grow later.

The content of Dean’s movies brought the type more clearly in focus. The leather jacket brigade were given a label—Rebel. They were supplied with a cause. They were strongly told they were not responsible for juvenile delinquency. According to the movies, their parents were to blame. Seeing is believing! A new mob of boys appeared on the screen—and a new one in the audience. The new group would have walked out on Andy Hardy. Times had changed—and so had its hero.

Who are a few of the popular stars, he roes today? Take Elvis. Elvis Presley, the guy standing on the corner watching all the girls go by, became a movie star chiefly because of his records.

Elvis was a movie star the minute he stepped before the camera in “Love Me Tender.” He had never done any professional acting; in fact, he had never even taken an acting lesson. I was on the set one afternoon when Director Robert Webb told Elvis: “When you do this scene, don’t try to act. Just be yourself. Acting will spoil you.

Don’t be fooled. Elvis is a natural actor, and he is always acting. He knows what he’s doing every second of every wiggle. Elvis confided to a friend that he had studied Jimmy Dean. He decided to be Dean with a guitar and a song. Elvis knew he couldn’t carbon copy Dean in appearance, but he had learned a basic requisite which appealed to teen-agers. Elvis, in his act, closed his brooding eyes and shook his body—sent himself—when he sang. This projected the feeling that he was poised on the brink of self-destruction. Teen-agers got the message. Elvis got the millions.

Many teen-agers identify themselves with Elvis from music to haircut. He is their latest idol. They rebel against their parents for him. Meanwhile, Elvis is a model son, who obeys his parents. He treats them to a month’s vacation in Hollywood. He buys them a new house, all with money anguished parents have given their teen- agers for temporary peace. You ain’t nothing but a hound dog, Elvis—but you earned your success.

And in Elvis’ wake, other singers rock ’n’ rolled to fame. Close on his heels came Pat Boone, followed by Tab Hunter, and more recently, Andy Griffith and Tommy Sands. While singers rate high, there are others: Paul Newman, so like Brando in looks that at first it was a handicap, and eighteen-year-old Sal Mineo, John Saxon, Nick Adams, James MacArthur. From the Actors Studio assembly line came Ben Gazzara and Tony Franciosa. And still of similar cut, from the stand- point of individualism and nonconformity, are Don Murray and Anthony Perkins.

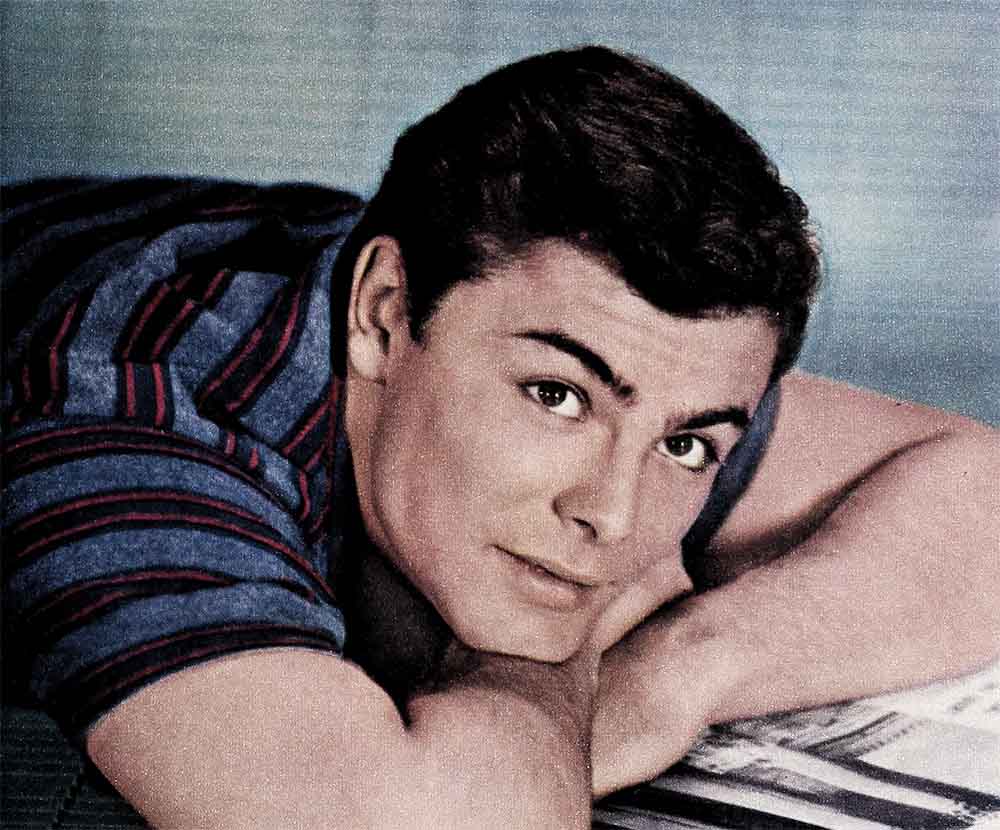

Tony Perkins goes Presley one better in one department. Perkins became a movie star without a hit record, and without having been seen in a movie. A great trick. (I’m discounting “The Actress” in which Perkins had a supporting role four years ago.)

Perkins was discovered, publicized, pushed into stardom by columnists (I was a chief offender) and movie magazines. He was a star before the public saw him in his first movie, “Friendly Persuasion.” And in which he oddly enough had only a supporting role. Perkins is proof that a new face can become a marquee name overnight.

Producers believe what they read, too. Perkins’ salary bolted from $25,000 a picture to $100,000 a picture before “Fear Strikes Out” (in which Tony proves he can act) was released.

Tony, who’s compared with Gary Cooper (I wonder whom they compare Cooper with?), does his best acting off-screen. He plays at being a character; walking barefooted down four prominent Sunset Boulevard blocks, from the Chateau Marmont to Schwab’s. Pretends he doesn’t want publicity, but manages to meet columnists. He drops news items while casually conversing with press agents. He writes friendly persuasion postcards to members of the press, whenever he is out of town. And he’s intelligent and quick.

“How does it feel to be a star?” Perkins was asked. Perkins replied: “Perhaps this will answer the question. On the set of ‘Friendly Persuasion, when I was introduced to a person, I caught him looking over my shoulder at Gary Cooper. Now when I’m introduced to a person he looks straight at me.”

Tony Perkins is, however, representative of the new group of actors who are intelligent, sensitive, confused; but in reality whose weakness is their strength. Admirers feel it’s their duty to take care of the Perkins type. The new movie heroes may not be as rugged as the old favorites, but most of them are smarter. They fight their battles in the mind, not by slugging it out in dirty T-shirts. (Witness Jimmy MacArthur in “The Young Stranger.”)

Tab Hunter is Tony Perkins’ friend. Tab belongs to the fraternity who have been odd-named by agent Henry Willson. Tab had been idle for over a year, after playing in the hit “Battle Cry.” Nothing much happened after that. Then Tab recorded “Young Love” for Dot. A month after the record was released, it sold a million pressings. Tab was awarded the Gold Record, the Oscar of the recording business. A prize many veteran singers have yet to win. Tab’s recording jolted his studio. They began to realize his potential. A new kind of hero was emerging and Tab was one of them.

The trend is much in evidence. The rebel has been cleaned up—literally. He no longer mumbles along in a sloppy T-shirt. More often, he’s looking positively dapper. Ben Gazzara, in “The Strange One,” carried on his evil doings in a spotless uniform. In the homespun “Friendly Persuasion,” Tony Perkins’ plaid shirts were not only freshly laundered, but proper fitting. James MacArthur, John Kerr and Tony Curtis struggle in button-down collars.

And while former heroes seemed to find discovery on an analyst’s couch, new film-throbs are found on campuses. The change? Not quite romance material, but at least they discuss their neuroses in complete sentences.

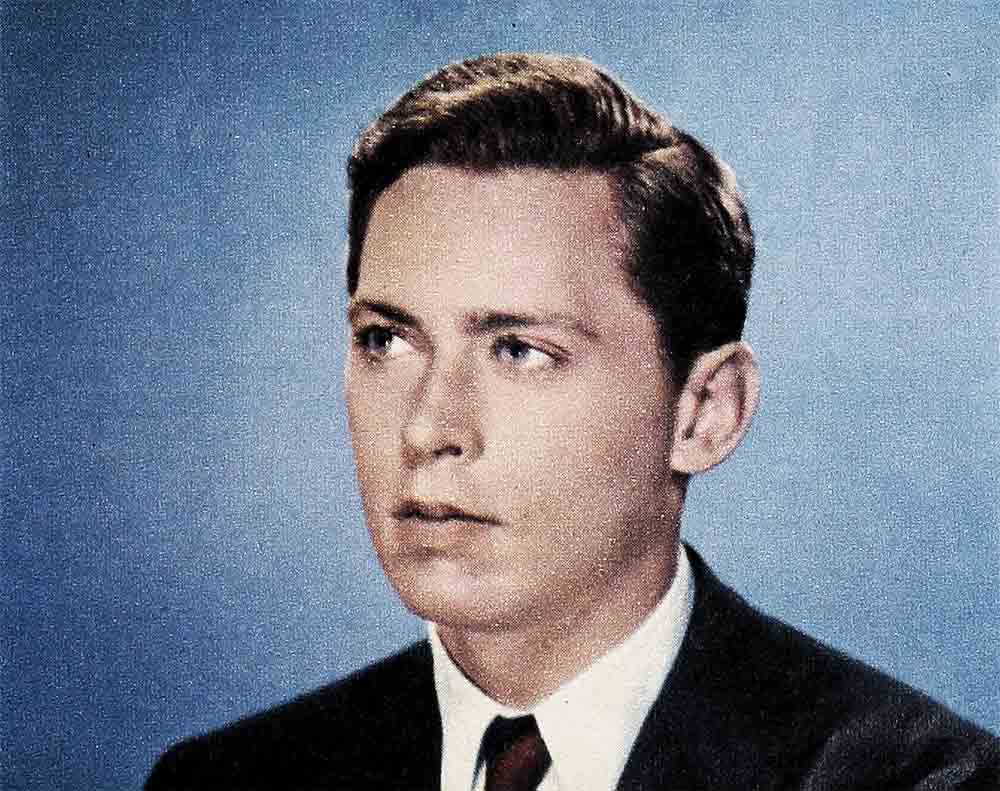

Paul Newman went to Yale Drama School; Jack Lemmon to Harvard. Pat Boone aims for Phi Beta Kappa along with his Columbia degree and John Kerr is a Harvard graduate, which James MacArthur will be (he entered Harvard last fall, makes films only between school sessions) . Sal Mineo, also intent upon finishing college, juggles classes between films; goes to U.C.L.A. and Long Island’s Adelphi College.

Their education shows. Paul Newman’s an excellent chef who takes special pride in his “Newman Celery Salad,” maintains “I like my comfort,” but dresses impeccably in neat slacks, loose-fitting jackets and soft moccasins. He “reads good books, fiction and non-fiction far into the night.” John Kerr, an Ivy Leaguer who looks “on campus” when off, reads classics “but wouldn’t work a crossword puzzle,” writes jingles, leans towards gourmet’s tastes in food. Pat Boone, who can rock ’n’ roll with the best, lugs, along with a heavy schedule, a suitcase of textbooks when on tour. Don Murray never seeks publicity, dresses and lives quietly, is as interested in social work as in acting.

Those who expect Ben Gazzara and Tony Franciosa to be mumbling, scratching characters are in for a shock. They are neither—scratchers nor mumblers. And their attitudes toward their careers? They are exciting. They regard good acting as a calling. Gazzara relaxes with canvas and a cookbook. Tony Franciosa, latest representative of the Actors Studio to make it big, with “a good biography.”

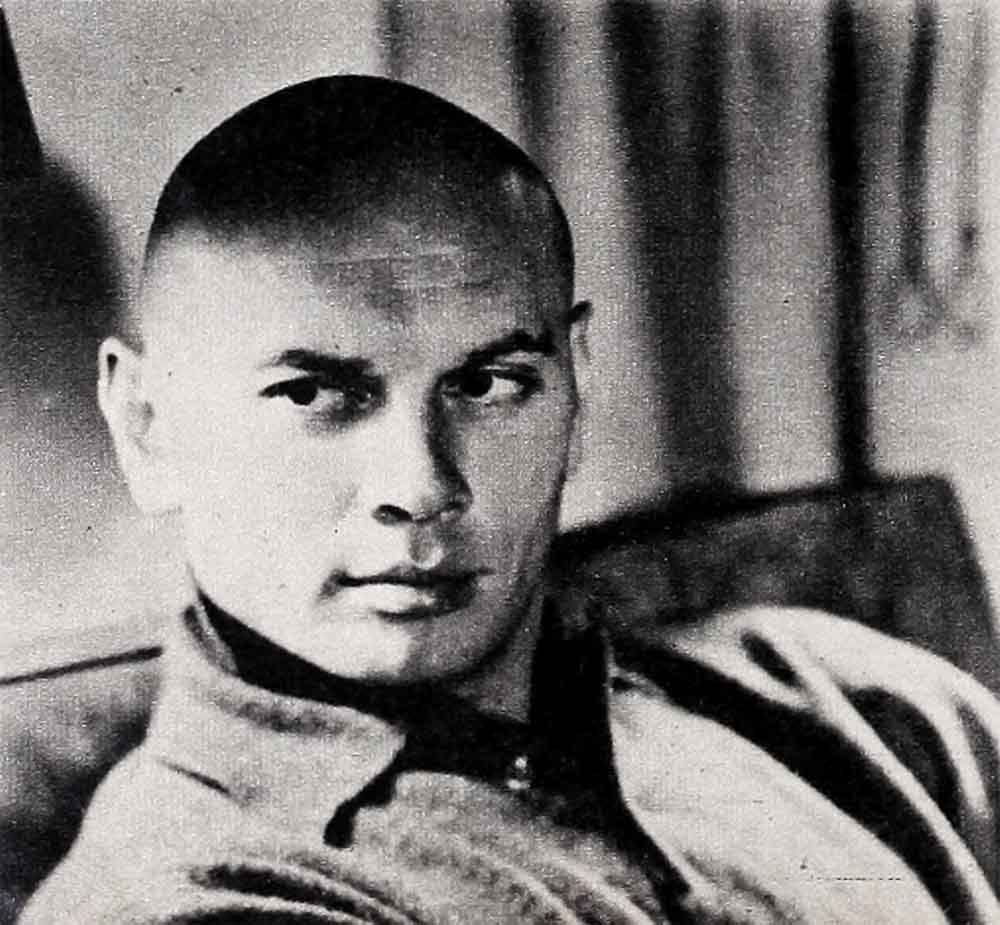

So granted things change, maybe improve—for the teen-agers. But leave me go with one thought—for a woman over twenty-five, other than a Yul Brynner or a Rock Hudson—who, in the new crop, is strong enough today to lift a woman into romance? Got you stumped, huh?

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1957