Why Jack Lemmon Left His Wife?

I don’t get the separation of the Jack Lemmons. I’ve talked with both Jack and Cynthia (not together) for hours—and I repeat, I don’t get it.

You’ll pardon me if I say that I’ve been a reporter for so long and I’ve seen so many Hollywood marriages go on the rocks that I feel I can usually ferret out the true story behind a divorce no matter what the principals tell me.

It’s sometimes, too often in fact, another man or another woman. Now and then it’s money—a lack of it, or too much of it. Sometimes it’s because gaudy, blinding, intoxicating success has come too suddenly and either the man or the wife “goes Hollywood.”

But these young Lemmons, both so sensible, so level-headed, just moved into their new home, both so devoted to their baby, Christopher—what in the world happened to them?

“Our marriage wasn’t good,” Jack told me in an emotionless manner of speaking. “There was nothing we could do so save it.”

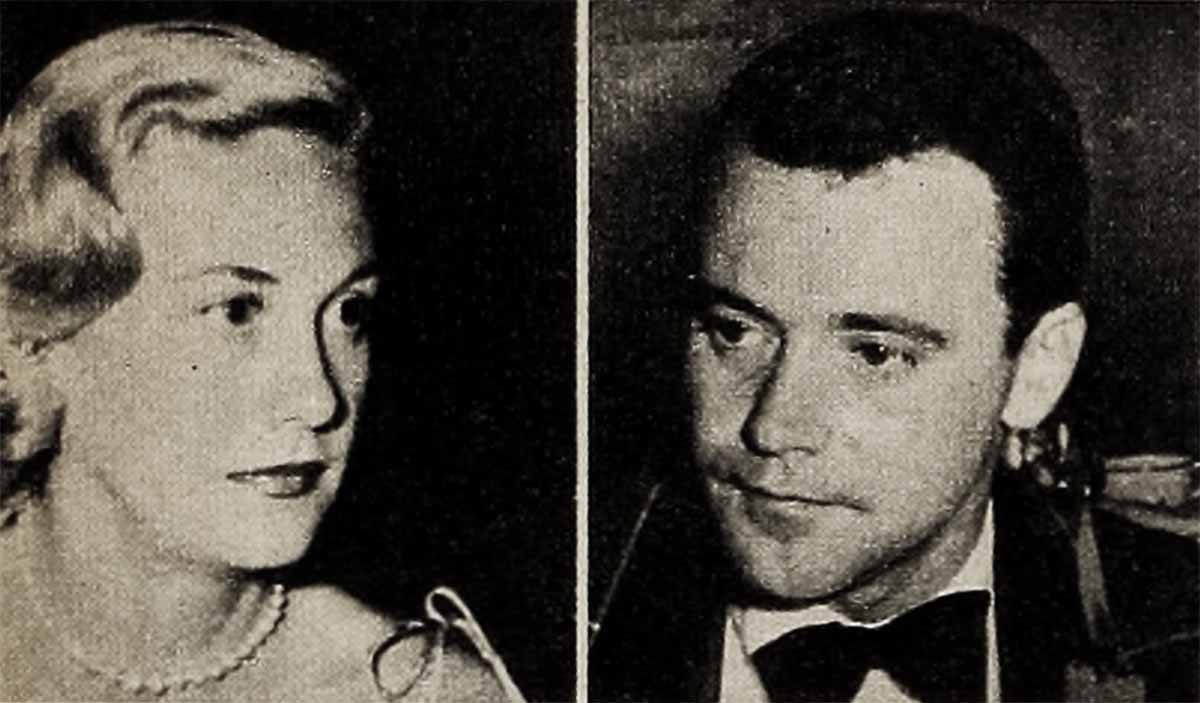

This young man who recently won an Oscar for his charming supporting performance in Mister Roberts was nowhere near as blithe as he was in that film as he sat in my playroom on a cloudy afternoon and sipped a cocktail. Neither was he seemingly depressed. His attitude was that of a fatalist up against a problem for which he saw no workable solution.

I have much more to say about my talk with Jack. But here I want to digress for a moment to my meeting with Cynthia Lemmon (the former Cynthia Stone) who came to my home, at my invitation, a few days after I had talked with Jack.

She is a lovely-looking girl with blonde hair and, I think, the most enormous brown eyes I’ve ever seen. She looks and dresses like a model although her clothes are not expensive. Altogether, she is a most attractive woman.

Cynthia knew, of course, that I wanted to talk about her separation from Jack. She hadn’t been there more than a few moments before she practically echoed Jack’s remark word for word, “Our marriage just wasn’t good. We tried.” It was almost as though they had coached one another. We talked for a little while about all the rumors that had cropped up since their parting.

And then, suddenly, out of the blue—Cynthia burst into tears!

“I don’t want you to think I asked you here to give you a third degree,” I told her. She looked so young, so distressed, so lonely and I felt very sorry for her.

“Oh, it isn’t that!” she said, speaking quickly. “There are just so many things I would like for you to understand. The most untrue gossip about us is the whisper that there is some other woman involved. One of the columnists said that Jack was again seeing Melissa Weston.”

Naturally, I had also heard the talk that Jack could not forget the very social and pretty Melissa, whom he had met through the Gary Coopers.

“Jack met Miss Weston when we were separated before,” Cynthia, now again in full possession of herself, went on. “Yes, this is the second time we have separated. But he never saw her except with a group of friends and it was just as ridiculous the first time it was printed that they were romantic about each other as it is now.

“As for those snide rumors that he became interested in June Allyson while they were making It Happened One Night—they are not worth dignifying with a denial. This is the most far-fetched gossip of all. Both June and Dick Powell, who was the director on the picture Jack and June made together, for heaven’s sake, are close friends of ours.”

I laughed. “All right, Cynthia. I believe you. But it’s hard for me to believe either of you when you say there’s no hope for your marriage. Tell me—where is Jack right this minute?”

“He’s home—baby sitting with little two-year-old Cris while I’m here talking to you,” she said, and for the first time she laughed.

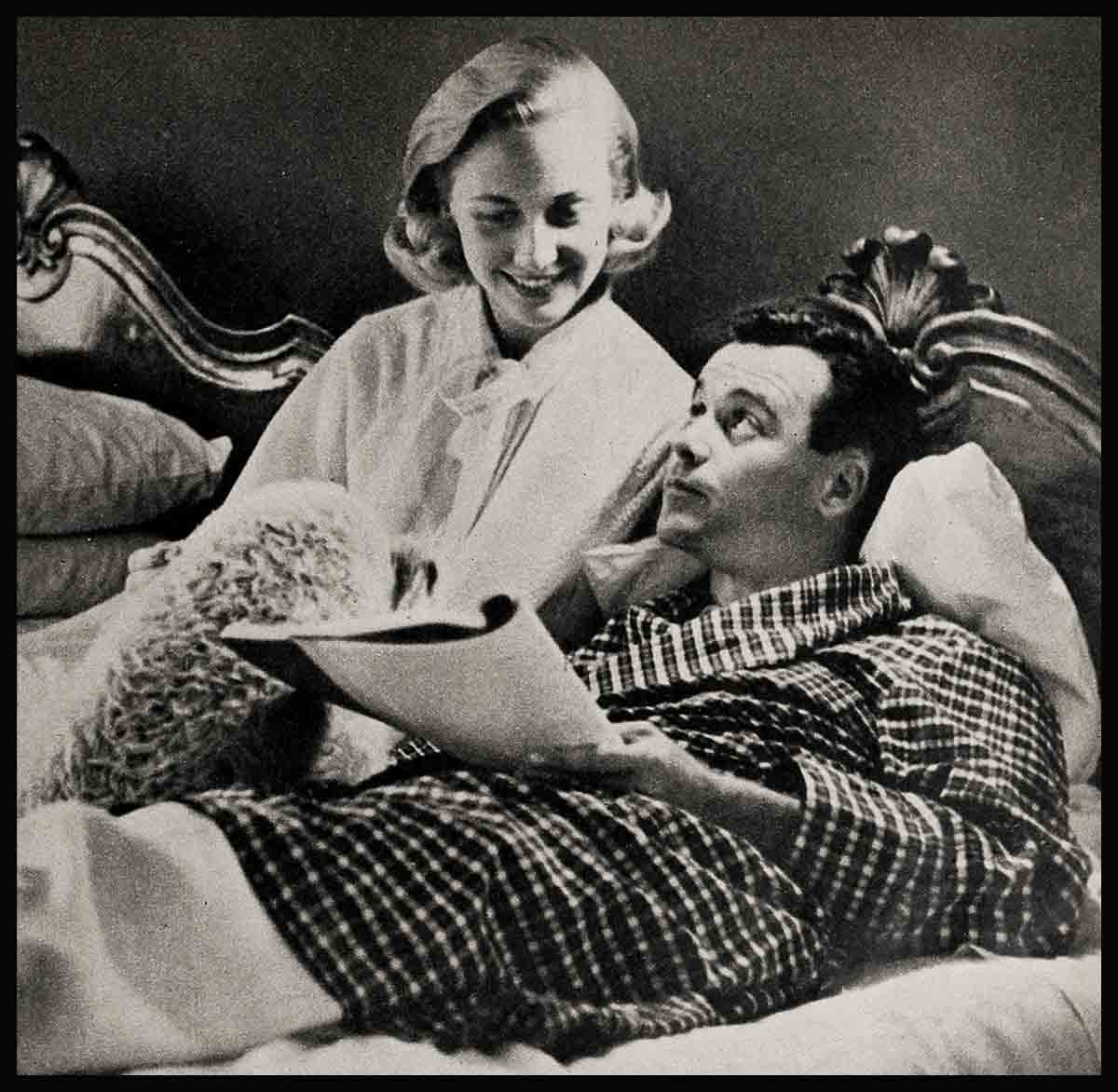

“And, when Jack called me on the telephone to tell me that you two were separating he admitted that he was home with the flu and that you were taking care of him. Really, if this isn’t the craziest, I’ve never heard it!”

Children of divorce

Now—as they say in the movie scripts—let’s flash back to Jack and what he told me the day we had our long talk.

You remember he, too, had said, “Our Marriage isn’t good”—and he went on, “I didn’t feel our baby should be brought up in a home where there was bound to be tension, quarreling and unhappiness.”

“Then you had been quarreling?” I asked.

“No, we didn’t quarrel,” was the paradoxical reply young Lemmon gave me. “But we both knew we were headed for unhappiness. We both have such dread of inflicting unhappiness on the little human being we love the most, our baby.

“Cynthia and I are both children of unhappy marriages. My parents didn’t separate until I was eighteen. That’s even harder than if I’d been younger. For many years I knew how unhappy they were together, holding on to something no longer lovely just for my sake.”

It is not hard to find out that Jack has enormous admiration for his father, who is the head of The Doughnut Company, a concern that makes mixes for baking.

“My father started in a small way,” Jack went on, obviously eager to talk about the senior Lemmon. “His business grew to be a tremendous success. He had hoped that I would come into the firm, but when I was at college I used to appear in the amateur plays and I knew I wanted to become an actor. My father never objected.”

I thought to myself—I don’t believe either your father or mother have ever objected to anything you wanted to do. When he up and decided, “He runs faster who runs alone,” and decided to say au revoir to his wife and child, the parents probably said, “God bless you,” and let him do as he pleased.

Jack’s father was in Europe at the time of the separation from Cynthia, and so Jack moved into the elder Lemmon’s apartment—that is, when he didn’t have the flu and went home to his wife.

“Do you feel that you and Cynthia are incompatible?” I went on, scouting other fields in this puzzling parting.

“Not at all,” was his surprising reply—if anything he could say could really surprise me at this point. “Cynthia and I like the same things—we like the theatre and movies, and we also have many friends outside our careers. One is a painter, one a writer. Our closest friends are the Richard Quines—he was my director on My Sister Eileen, you know. June and Stu Erwin are other good companions.”

What do your friends think?

I asked, “What about Jimmy Cagney?” I had seen Jack and Jimmy and Mrs. Cagney and the Ralph Bellamys all having dinner together the night after Jack told me that he and Cynthia were parting.

“I never knew Jimmy until we made Mister Roberts,” Jack answered. “We became very close friends during the making of the picture. I have great admiration for him as an actor and a person.”

“But, what does he think of this separation?” I asked, knowing that Jimmy has been happily married for years and years and couldn’t help but think the parting of the young Lemmons strange indeed.

“We never discussed it,” Jack replied. “Cynthia and I sent notes to our families and our friends about our decision—and then I called you up.”

“Perhaps you should talk about it to your friends,” I persisted, “and you and Cynthia should talk about it. There’s got to be some reason.” I took another shot in the dark. “Did you object to Cynthia’s making several TV shows and continuing with her own career? Two careers under one roof have upset more than one happy Hollywood home, you know.”

Jack shook his head. “That’s silly. She is talented and should have a career if she wants it.”

I tried one more angle with this young man who sounded more and more as if he was talking about his best friend and not the wife he is leaving—or rather, has left.

“Do you think that Hollywood came between you? The glamor of big success, your winning the coveted Oscar, all the heavy attention you are getting?” was my question.

Jack said, “As I told you before, my family is prosperous. I had it good as a kid and a young man. It isn’t as though I had fallen into good living after I came to Hollywood. I can tell you in all truthfulness that nobody is as happy over my success as Cynthia—and nobody gives me better advice on my acting.”

So I gave up on that angle. Here is this boy, John Lemmon III, who has never been denied anything and success literally has been laid at his feet. You would think that he and Cynthia would be the two happiest people in the world, having everything that life holds dear for attractive young people, a home, a child and fame.

Then suddenly they decide, “Oh, no, we want to live our own lives.” It doesn’t make sense.

To say that Cynthia hasn’t been a big help to Jack wouldn’t be telling the truth, and he is quick to give her great credit. She is pretty, she is charming, she is young—and everyone who meets her likes her. Everyone likes Jack, too. He has a great sense of humor, he speaks well and he is a nice boy. Why all this sudden urge to throw off the shackles and go it alone?

“I honestly don’t think our marriage has any chance of being a happy one,” he repeated doggedly—and there we were, right back where we started from.

Chris will be happier!

Several days later, I repeated to Cynthia what I had failed to get out of Jack, “What really brought this about?” I was quite surprised to find out, as we talked, that she too put great emphasis on the unhappy lives together of her parents, just as Jack had.

“Both Jack and I were brought up in homes where there was no love,” she told me some time after she had had her little crying spell. “My mother died when I was about seventeen—but she and my father didn’t speak half the time. It was pretty miserable for me.

“I figure if Jack and I are headed for that kind of marriage it is better to separate while Chris is little. Then, if I marry again and Jack marries again, we can share him in happy homes.”

This seemed curious reasoning. I said, “Broken marriages are said to be the cause of so many unhappy children.”

“I don’t believe it,” Cynthia protested, “Chris could grow up seeing me happy and Jack happy—even if we aren’t under the same roof. I’m young, and I hope to make a good marriage.”

I threw up my hands. “I give up,” I conceded, “here you aren’t even divorced and you’re talking of future good marriages. Are you so fully convinced that there isn’t a chance of reconciliation? After all, you and Jack have survived six years of marriage on what I am beginning to believe must have been on the friendliest terms I have ever heard!”

Cynthia smiled, “I’m sure it must be puzzling to an outsider. But you see, Jack and I don’t believe in fooling ourselves. You know I come from Pontiac, not far from your home town of Dixon, Ill. We mid-westerners at least try to be forthright and honest with ourselves. Isn’t that so?

“Don’t forget that Jack and I married quite young—perhaps drawn together in the beginning by our mutually unhappy childhoods. We were both struggling for a foothold and we made so many TV shows—which is where we got our start—that we had never had time to really know each other. We just worked, worked, worked.

“Then Hollywood came along—and I’m sure I don’t have to repeat that story to you. Success was not long in coming to Jack—and with success came leisure, between pictures, at least.

“In six years we had matured—and do you know what we found? That we were the best friends in the world. But we were not happy as man and wife.”

Now we were getting someplace, if you ask me—and I hope you do. I have had much time to think about the young Lemmons since my talks with them.

If they only knew

I sincerely believe that they have reached that point that comes in all marriages when the romantic glow of boy-and-girl love has grown into something really more wonderful—if they would only realize it.

I’m talking about the companionship and yes, good friendship that is the real basis of a lasting marriage. It can’t all be moonlight and thrills—like it is in movie scripts. Real people don’t live like that.

The Lemmons, I believe, are going through this transition. If they can just be careful—if they will just be smart and stop and think about what they may be losing, I think there is a big chance for them to get together again.

Perhaps it won’t has already left for Trinidad, where he will make Fire Down Below with Rita Hayworth. The picture will be several months shooting.

I think he was glad to go—at this time. I also think that Cynthia is relieved at this reprieve of a couple of continents and the Atlantic Ocean between them. This chance to be apart and maybe discover just what they do mean to one another may be just the thing they need.

I certainly hope so, for I like them both very much.

As Cynthia said before she left my house, “Jack and I are still such good friends that we went to the same party a few nights ago. Not together, you understand,” she put in hurriedly, “but we had both been invited and we didn’t want to embarrass our host and hostesses by making them choose sides by inviting one or the other of us. We want to keep it that way. When Jack comes back—we will see each other.”

I certainly hope so, Cynthia. I hope you will see each other as you really are—two young people who have too much between you, too many of the good things of life, ever to lose them—apart.

THE END

—BY LOUELLA PARSONS

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1956