Can An Actor Stay Good?—Pat Boone

Boone greeted Photoplay’s photographer at the door of the Boones’ modest suburban home in Leonia, N. J., with a warm smile and a firm handclasp.

“Come in,” she said. “Pat’s upstairs. You can go right up.”

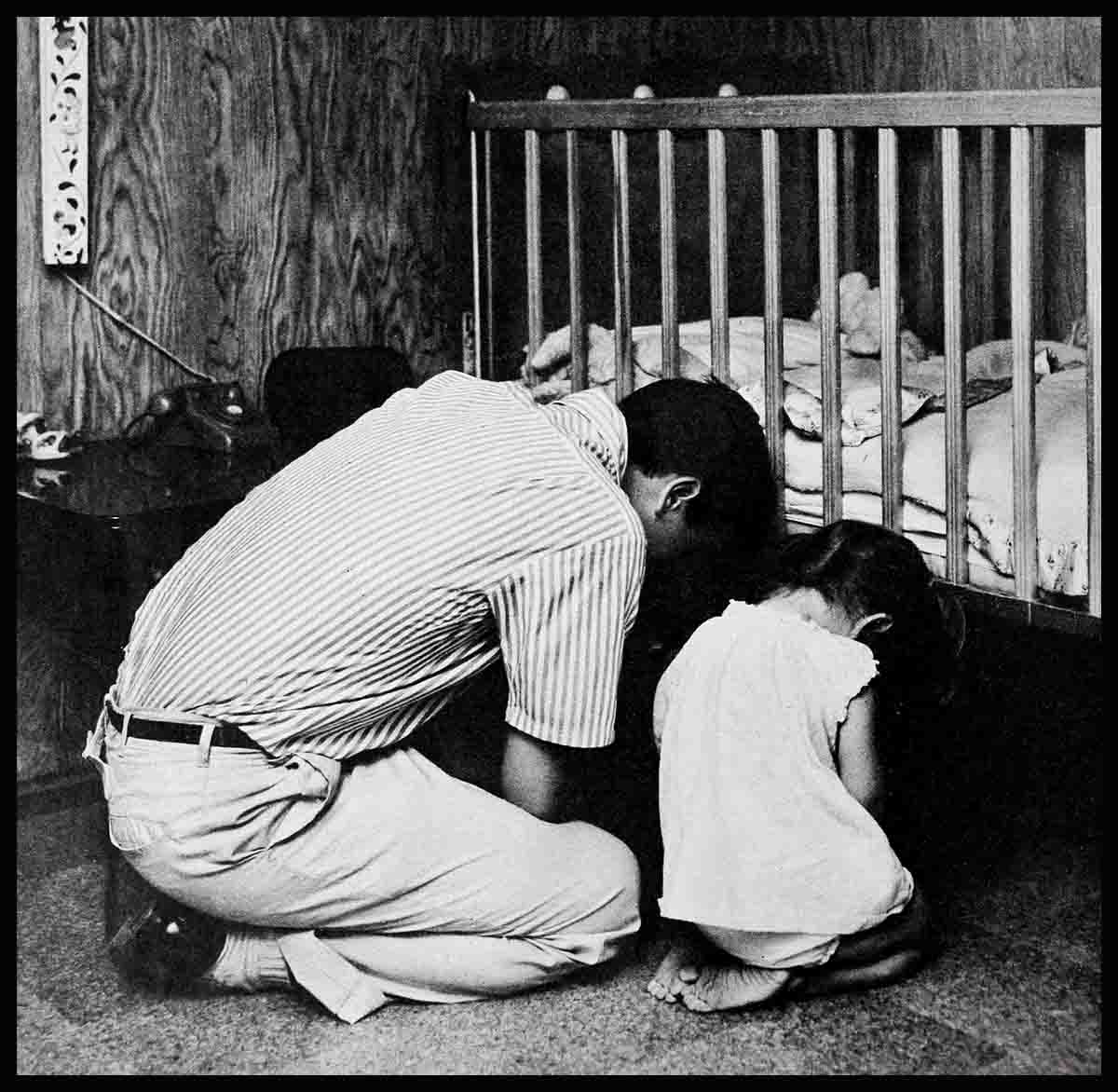

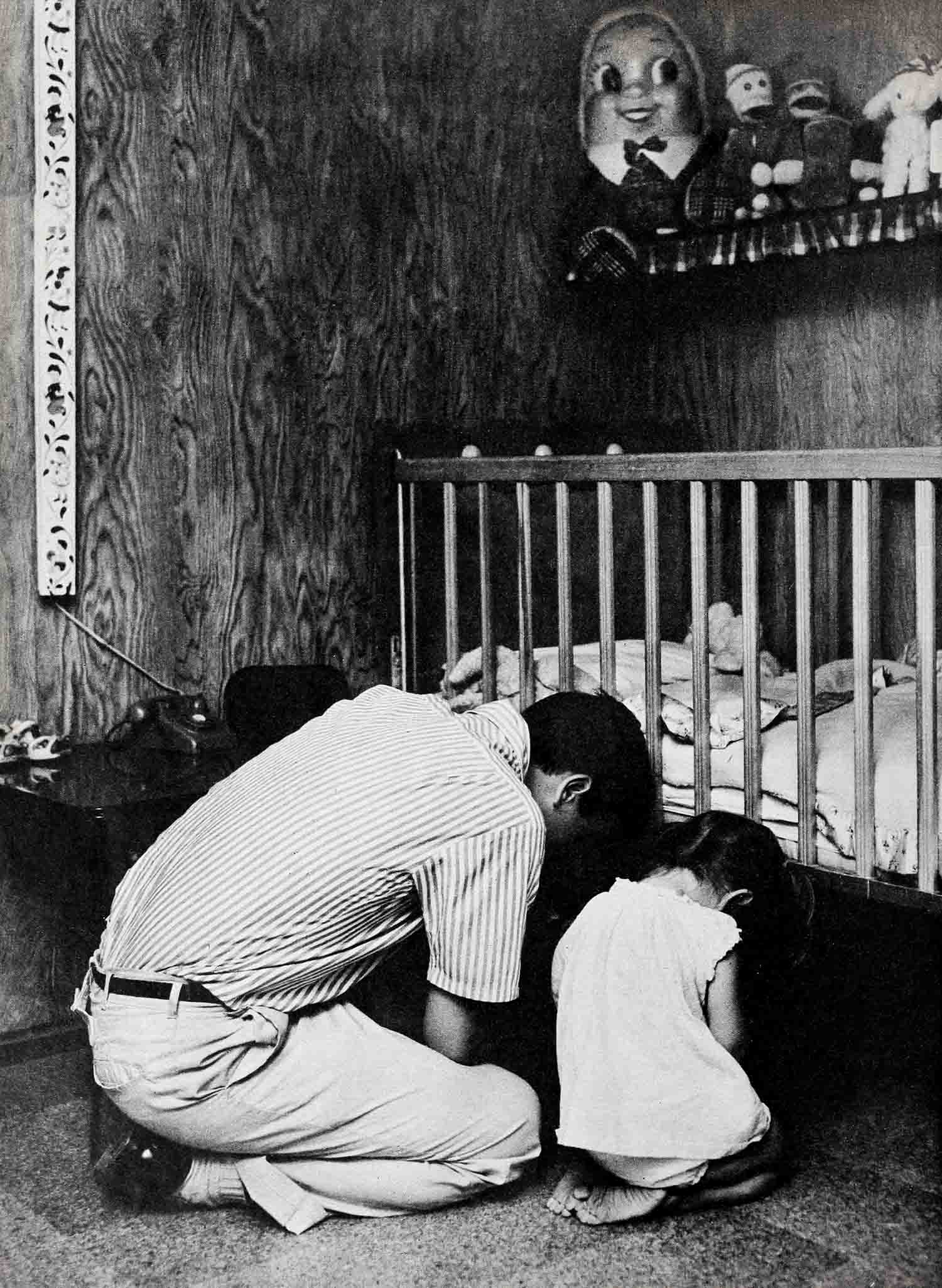

Tiptoeing lest he disturb the baby Boones at their afternoon naps, our lensman mounted the stairs. From a room down the hall came a clear, childish treble, “. . . and God bless Rin Tin Tin. . .”

As three-year-old Cherry Boone rattled off the rest of her beloved TV favorites, he stole to the doorway and snapped the lovely picture on the opposite page.

Although taken unaware in this photo, Pat Boone, who stands firmly at the very top of the entertainment world, is one actor who is not ashamed to be pictured on his knees.

In a modest white church on Rossmore Avenue, a few blocks from Hollywood’s Tin Pan Alley, or in a simple house of worship dwarfed by huge apartment houses in New York’s teeming East Eighties, not far from the blare of Broadway, Pat Boone often leads the congregation of the Church of Christ in an old hymn:

“Saviour, lead me lest I stray,

Gently lead me all the way.

I am safe when by Thy side,

I will in Thy love abide.”

He has known the hymn by heart since he was ten. But today, the words have a new, deeper, and very personal meaning for him, for Pat Boone’s faith is being put to the test every day with ever increasing pressure, and he clearly knows it.

Following up the great success of his first movie, “Bernardine,” 20th Century-Fox promptly offered Pat the starring role in another film, “April Love.” Like “Bernardine,” which he heartily approved because it presented teenagers with sympathetic understanding, it is a charming, wholesome story, and he accepted it. His costar is to be the equally charming and wholesome Shirley Jones. But when Pat was shown the finished script, he balked. There was a scene in it in which he was to take Shirley in his arms and kiss her.

“I just can’t do that,” Pat explained to the flabbergasted executives. “It’s against my religion to put my arms around or kiss any woman except my wife.” For Hollywood, this was unheard of! After all, it was just playacting, advisers told him. Both Shirleys—Boone and Jones—would understand. Acting had to be realistic.

Pat stood his ground. The scene came out. In its place, the harried script-writers substituted one in which the kiss is merely suggested by a lipstick mark on Pat’s face.

Pat can’t help but realize that he was in a position to win this bout so easily because he is one of the hottest show business personalities today. With one hit record after another sweeping the country—his “Love Letters in the Sand” topped every record poll for weeks—who’s going to argue with him? But there may be other problems which he cannot cope with so easily. And what of the temptations that go with stardom and mounting material success? Won’t they make the decisions tougher, and the challenge greater?

Pat answers honestly, “I don’t know. So far I haven’t found it to be that way. I may be wrong, but as I look to the future, it seems to me that the higher you go, and the bigger position you get in, the more you can dictate your own movements.

“The pressure’s on when you’re just coming up. That’s when it’s rough in any business. If a fellow has certain principles and ideals that would prevent him from doing certain things he’s called on to do because they might help him in his career, that’s when he has to decide which is more important—a career or his faith and his conscience and his personal integrity. That’s when he has to come to grips with himself and decide what his faith really means to him,” Pat points out.

He admits, “There have been a few minor—and I guess maybe a few major—decisions to make along the way—”

From the day he entered show business, Pat Boone has turned down any offers for television shows or personal appearances, no matter how lucrative, where the show or rehearsal would have made it impossible for him to attend church “at least once on Sunday.”

And from the beginning—he’s ruled out sponsorship of TV shows by any products he couldn’t conscientiously sell, no matter how golden the budget or the seeming future.

“There was one in particular,” Pat recalls. “I was offered my own show with a big budget immediately following “The $64,000 Question’ on the same network. You know, that means there’s a big audience left over from that show, and if you grab a tight hold, maybe you’ll have a good chance to keep them with you half an hour. And that would have been a great thing. But the show was sponsored by a cigarette company and I personally didn’t feel I could conscientiously advertise cigarettes—since I don’t smoke myself and I don’t feel it’s a healthy thing.”

Still, this was so tempting that Pat weakened. He told the agency there was one possible way he could do the show. With restrictions. Telling viewers something to the effect, “I don’t smoke, and I don’t think you should smoke—but if you’re going to smoke—why not smoke the best?”

Thinking that over, the agency decided such a novel approach just might sell cigarettes. Immediately, Pat saw that, for him, this was wrong. He says, “I thought, ‘well, if it does sell cigarettes, it will be defeating my own purpose.’ So I had to tell them I wouldn’t do it.”

He never takes a drink, although be believes he could take one in moderation and, like others, he would enjoy it. But as Pat says, “There are many religious people who believe it’s wrong and who might not believe I’m sincere in my religion if I did it—and I’d rather not.” More important, he feels, is the possible influence on teenagers. “Some of them are just not physically or emotionally equipped to handle a drink, and if my influence was responsible for even leading just one of them toward that, it would be too heavy a price to pay for any enjoyment I might get out of it.”

Pat’s stand on drinking was not put to the test until he made “Bernardine.” One scene called for his father to offer him his first drink, by way of celebrating a family event. “I was just a high school senior in the picture, and I objected to that scene,” Pat says. “I thought it didn’t seem right for a father to offer his teenage son a drink of whisky. The studio was nice about it. They saw my point and changed the scene.”

Pat weighed another one involving a boyish escapade in which he was to order a beer for a pal who was also underage. “I questioned this at first—just because I wouldn’t do something like that myself. However, when I play a part in a movie I‘m playing somebody else, not Pat Boone. And in the scene it was made very plain the movie didn’t condone it, that the boys were doing something they weren’t supposed to do.

“If I’m going to be in movies, I’ve got to decide whether I won’t play a character who does things I wouldn’t do personally or not,” Pat goes on. “For the moment at least, although I may change my mind later, I’ve decided playing a character is a lot different.”

Whatever Pat Boone’s decisions, his religious background makes him an unusual target for well-intentioned criticism and advice. This he appreciates, but it can be confusing, and thus make his position more difficult.

“People do consider me a religious person, interested in my own soul and my influence, and this puts me in the position of being watched carefully. Since some take one view and some another, I’m bound not to be able to please everybody. I’ll just try—as nearly as I can—to do the right thing—act according to my own conscience.’

The faith of which Pat says, “It’s the foundation for everything I do,” was early inspired by the teachings and the example of Pat’s parents. His deeply father, Archie Boone, a study in calm strength and quiet authority. His mother, attractive, energetic Margaret Boone, of whom Pat says, “Mama is inexhaustible.”

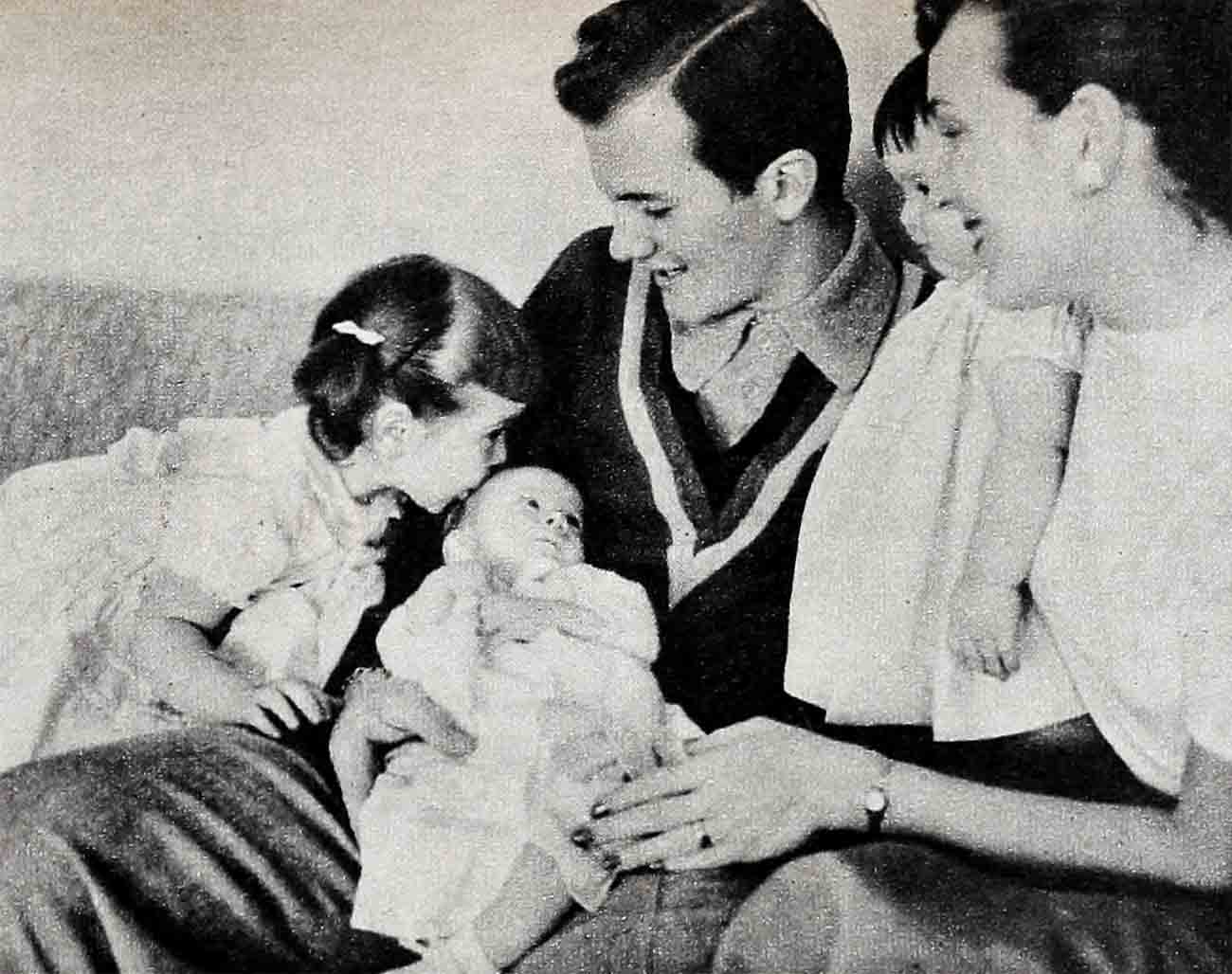

“Theirs is the kind of influence I want to have on my own children,” Pat says warmly now. His father is a deacon in the Church Of Christ in Nashville. As for his mother, “From the time I was six weeks old, my mother carried me to church. She went regularly, taking three babies with her then—my brother, Nick, my sister, Marge, and me. I don’t know how she managed. Sometimes Shirley and I can’t do it with our three and we have some- body to help us!”

When he was twelve years old Pat was baptized and by the time he was fifteen, he was leading the singing for a congregation at “Pegram Station—a very small place.”

During the important teen years, Pat Boone’s sense of religious and moral values was further inspired by Mack Craig, a minister of the Church Of Christ and principal of David Lipscomb High, whose accomplishments and humble Christian qualities were influential in making Pat vow his own life must have purpose and value that would last. There in high school he also met the pretty girl whose faith and courage throughout the future would reflect and strengthen Pat’s when he needed it most.

And pray the Lord my soul to keep.

If I should die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

God bless Mommy, God bless Daddy,

God bless Steve Allen,

God bless Arthur Godfrey,

God bless Rin Tin Tin . . .”

“Since I can remember—I’ve always tried to weigh and decide what’s right,” says Pat. “Not that I haven’t made a lot of mistakes. And not that I haven’t occasionally done things I knew were wrong. Everybody does. But at least in making big decisions I knew would affect my future life, I’ve always tried to decide the right thing, and the most useful thing to do. When Shirley and I eloped, we felt we were meant for each other. The Scripture says, ‘For this cause—a man shall leave his father and mother—and cleave unto his wife.’ ”

Because it seemed “right,” three months after their marriage, they broke away from all family ties, loaded their belongings into an old Chevrolet Pat had bought from his dad, and headed for the little town of Denton, Texas, where Mark Craig’s cousin had a chinchilla ranch. Pat planned to work there, sing wherever he could, and attend North Texas State Teachers’ College.

“We felt we should be on our own. We were in love—we had blind faith,” he says now.

As for the pretty girl riding beside him down the highway into the unknown—their first child on the way—there was no doubt. No fear.

“Pat was my faith,” Shirley says now. “I told my Daddy, no matter what Pat decided to do—I knew he would make it. But then, I don’t know anybody who didn’t have faith in him. I know Daddy felt the same way—”

So did Randy Wood, head of Dot Records, a little later. When he gambled on Pat—and two records turned into smash hits—there was another day of serious decision for Pat Boone. One of a pattern of many. In their little house in Denton one August day two years ago, before Pat Boone winged East to join Arthur Godfrey’s television cast—Pat and Shirley talked.

Now there was much to be weighed. He could finish at Columbia University and still teach. But another possible future had opened up out of the sky. An unlimited future stretching from Broadway to Hollywood.

Concerned always about “the useful thing”—what he could do that would live—teaching seemed the answer. There was a touch of the immortal there—a man giving of himself to others, influencing young minds, giving knowledge and values which might live on through them.

An entertainer’s audience could number millions. If he were successful he could give materially and morally and spiritually—and live on through those qualities. But a successful entertainer could belong in part to that public too. What if the demands of that world were too many? In the spotlight, every word, every deed, every decision—would be magnified many times. What if—?

A whole new challenging future—perhaps too challenging—

“We were concerned,” as Shirley says now. “We knew it was going to be a double row to hoe—doubly hard. And Pat wanted members of the church and religious people everywhere to have confidence in him, to know he would uphold his religion.”

There would be many of all faiths to whom show business represented too many demands and temptations. And to whom Hollywood would mean the mecca of all that was worldly . . .

There would be many—to whom the world of entertainment was so foreign—who would never realize just how many Christians worked therein. The devoutness of their faith—and how monumental the good they do . . .

There could be those among their own faith who might question Pat Boone’s wisdom in becoming part of that world—and question the strength of his own faith . . .

Pat Boone made his decision. He flew East—and the rightness of that decision—a good omen—again seemed to come right out of the sky.

“Pat was scheduled to go to Philadelphia for the dedication of a new television station. He was making an appearance in Chicago, and catching a plane immediately In Philadelphia there was a terrible storm. The station was demolished, four persons were killed and twenty-nine injured. I thought Pat was there—he had expected to be.”

That first agonizing hour, she could find out nothing. There was no trace of Pat. He’d left Chicago. There was no word of him in Philadelphia. When they connected “Pat was in New York with Randy Wood—he’d missed the plane—

“Then,” says Shirley, “I felt the Lord was with Pat, that there was a place for him.”

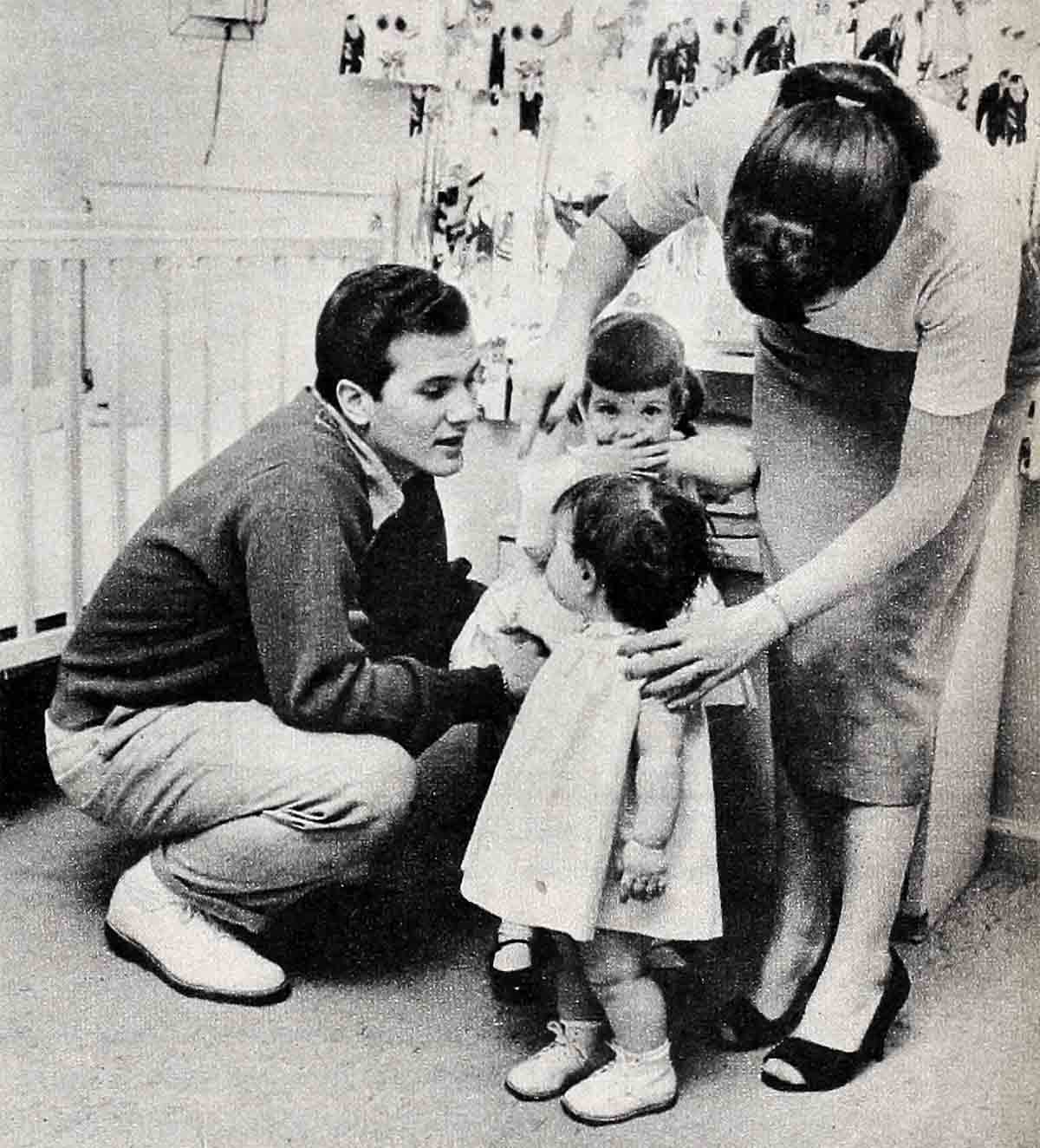

Of Shirley’s place in that future, and how her being of his faith helps, Pat Boone says, “Shirley’s just—invaluable. I don’t see how it would be possible for somebody to really hang on to his faith and make it a working thing in his life without the cooperation of his wife—because eventually there’s a wear and pull and tug on you.

“It’s like the Scripture says, ‘Leave behind the weights that so easily beset you—and press on,’” Pat goes on. “I think that means to leave behind you—to cut out of your life—all things that make it hard for you to live a clean wholesome life—a Christian life. It’s hard enough to do this anyway, but with a lot of hindrances—carrying extra weight—it would be much harder. A wife who cooperates and helps and strengthens you—makes it that much easier. Shirley feels and believes the same way I do and therefore my decisions have been that much easier.”

As for any possible “weights” that beset Pat now—or in that future—Shirley’s faith is with Pat’s all the way. “Pat’s already been challenged in many ways—and he’s come out on top,” she observes quietly. Adding, “I think whatever Pat does—he will feel is right. And if he doesn’t feel it’s right—he’ll quit the business before he will do it.”

“I get letters from members of all churches and all faiths who are concerned whether I will hang on to my own belief,” Pat says now. “Letters from people who think of show business being—too worldly, you know. I appreciate people of every faith praying for me and being interested in my spiritual welfare. This is a very humbling thing. More than that even—it makes me want to be sure I don’t disappoint.”

For Pat Boone’s faith is his real future.

“I figure unless I’m of use to others—then I will be a failure. No matter how much money I make or anything. You only live once and it’s a short time at most. People forget about you pretty soon. Unless you’ve left something worthwhile—unless you’ve helped other people—and unless you’ve left a good influence that will live on in other people’s lives—then pretty soon you’re really dead. But if you’ve left something worthwhile and lasting for other people—then you live on.”

With this goal Pat Boone takes a confident view of the way ahead.

“I don’t think it will be any harder in motion pictures or the entertainment field than it would be in almost any other field—except perhaps teaching or any kind of religious work. Not that there won’t be a lot of temptations—but I think there are just as many chances to neglect faith and religion in any business.”

The answer is knowing where you stand—and staying there. “Once you’ve made up your own mind to do something, it’s half-done then. If you have certain ideals and principles and you’re solid and firm about these things, as each thing comes up—each problem, each decision—then your decision’s already half-made . . . and it isn’t too hard.”

And if that day should come when he can’t do his job in show business in accordance with his own beliefs—if he finds he can’t have fame and keep his faith—that decision’s made too. As Pat Boone puts it, he’ll “just step aside.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1957