Star Performances You’ll Never See

Some of the best acting in Hollywood isn’t done for the benefit of the camera. In fact, many of the most electrifying performances witnessed have occurred when there wasn’t a photographer in sight.

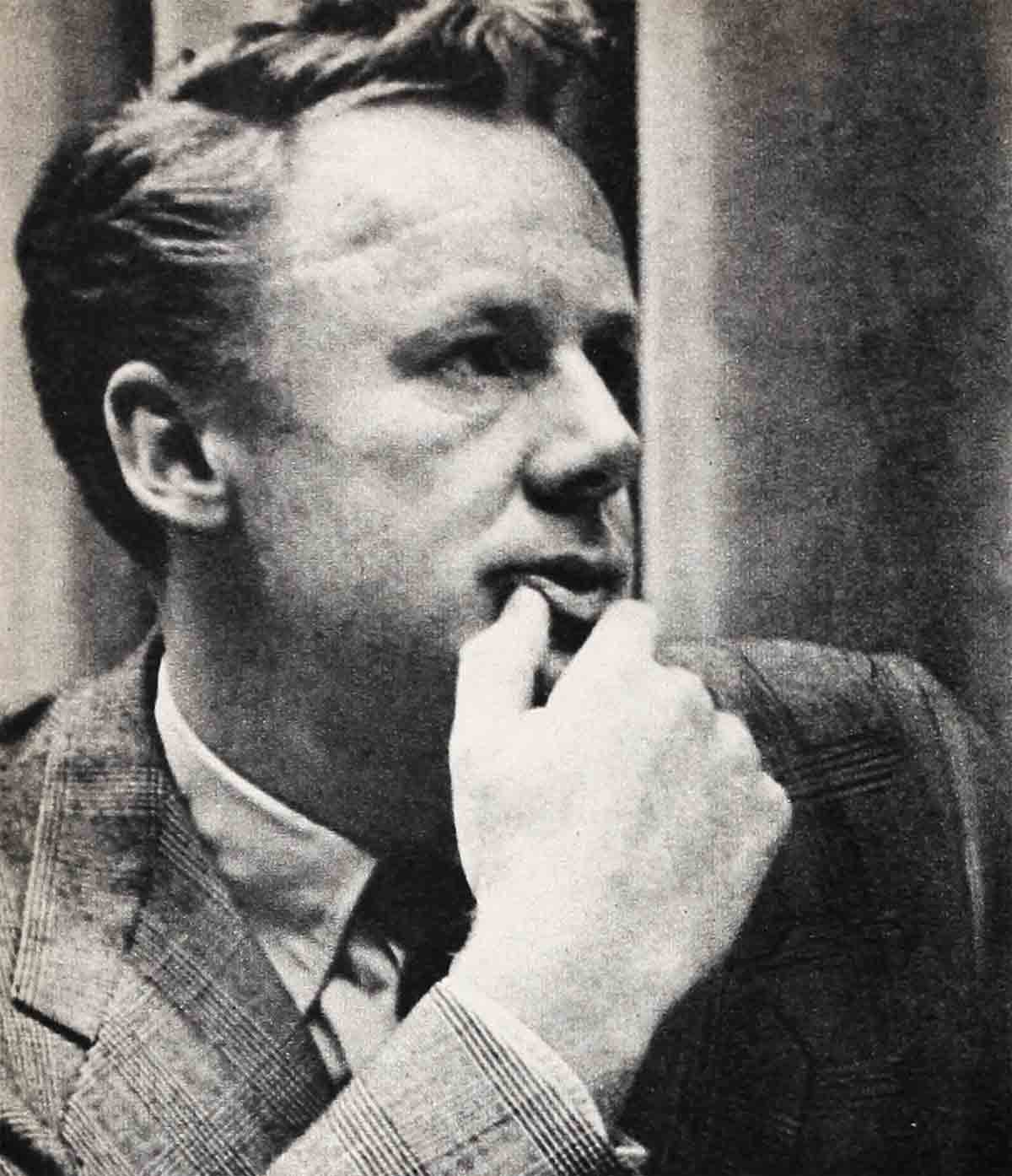

Take the night Van Johnson sat in Romanoff’s, along with other Hollywoodites, and awaited the announcement of the Academy Award nominations. Van, who was up for his fine performance in “The Caine Mutiny,” along with Humphrey Bogart, came alone without Evie. And before the TV presentation began, he and Bogey, who mc-ed part of the nominations, held fast repartee about: “Oh, I don’t really care, old man. It doesn’t make much difference.” But after the program started and the time drew nearer and nearer for the final top male nomination, Van showed signs of worry, was literally chewing his fingernails when the monitor started reading off the names in alphabetical order: “Humphrey Bogart—Marlon Brando—Bing Crosby—Dan O’Herlihy.” Then realizing that one name had been skipped, the monitor paused. Van sat rigid, waiting for the missing name—which alphabetically could be his. Then, as the monitor read off: “James Mason,” Van slumped into his chair and put his head on the table. For those around him, it was a moving experience. For there are times when a star’s acting talent fails him and he breaks down and lets his true feelings come through—those times when his heart tells him what he really wants.

In reverse, take a situation which involved Lucille Ball. Lucille’s a comedienne by nature. But she was more like Hamlet when she called me that terrible time from New York. One of her closest associates had revealed to me a piece of information which I had used in my column. When Lucille saw it, she insisted it was not true. She hollered long and loudly for twenty minutes without repeating herself once. The storm was spent as fast as it started. And Lucille and I are good friends. But I still haven’t exposed the erroneous news-giver, which, come to think of it, ought to give me a medal. Because, boy, oh boy, I’ve been tempted.

Debbie Reynolds was a doll in “Susan Slept Here.” She was great in “Singing in the Rain.” But her performance was at the big, glittering engagement party Eddie Cantor threw for her and Eddie Fisher at the elegant Crystal Room of the Beverly Hills Hotel last fall.

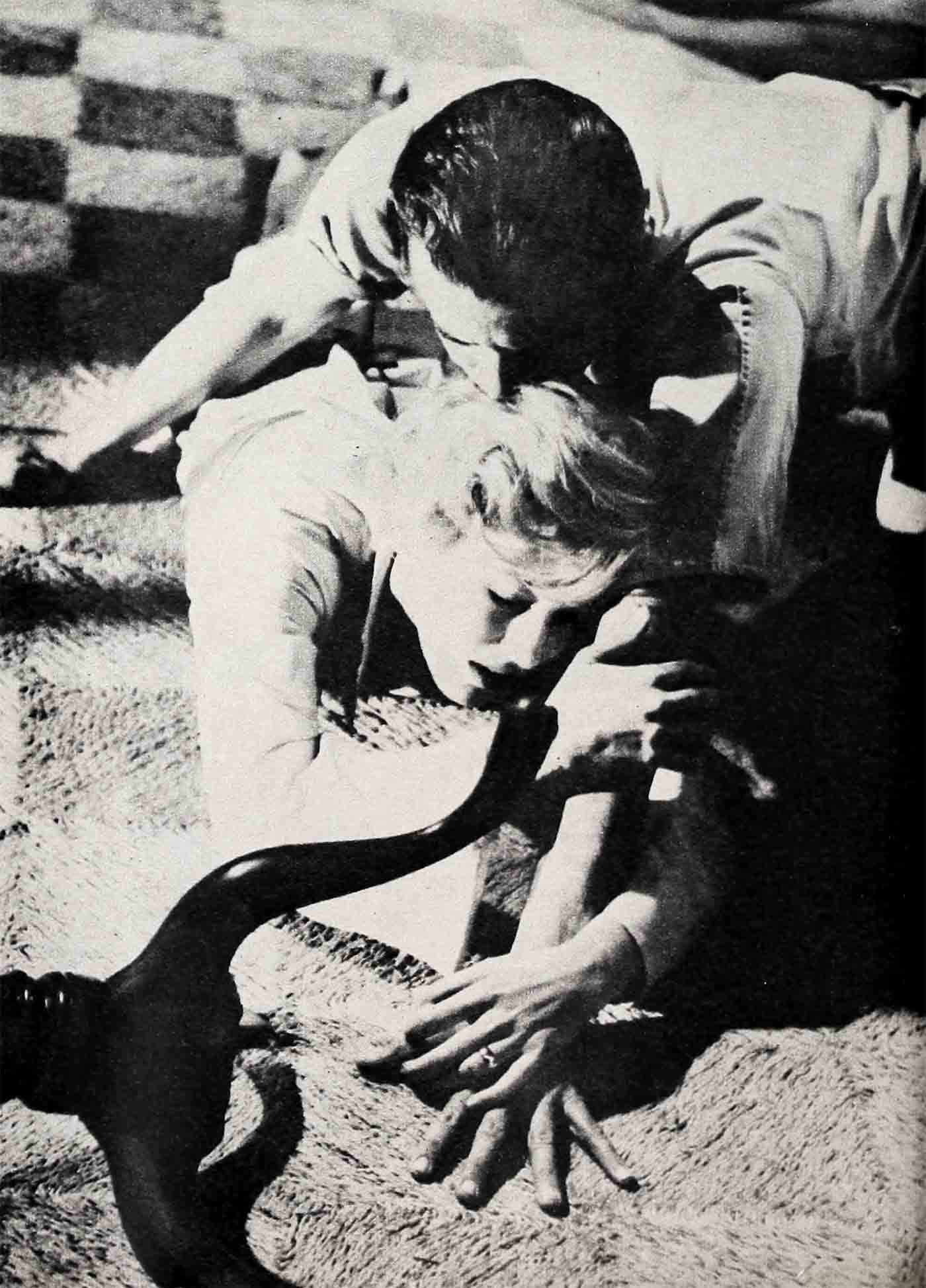

Of course that affair has been reported on before this from stem to stern, all except one incident that occurred when nobody was looking. Nobody except yours truly. Naturally Eddie was feeling very good for he’d just become engaged to one of the sweetest girls in the world. He began to express his happiness in the best way he knew how; he started singing. And he sang from the top of his lungs. Debbie was embarrassed. The flush on her cheeks didn’t come just from the excitement of the occasion. I was very interested to see how Debbie would handle the situation.

I needn’t have worried a bit. As they walked hand in hand across the hall, Eddie’s voice raised lustily in song, Debbie stopped, smiled up at him, gently put her finger to his lips and then kissed him full on the mouth. She achieved her purpose without saying a word. Eddie forgot to continue singing. In fact, all he wanted to do was to continue kissing. I didn’t blame him.

Bette Davis did her best acting in New York and I don’t mean in her stage flopperoo. At this time she was at Warners, the undisputed queen of the studio, and she was in the Big City for a personal appearance with one of her pictures. Before her arrival there, she sent a list of very explicit instructions as to how the suite at the St. Regis Hotel should be arranged, which room she wanted for herself and for her then-husband, William Grant Sherry, and for her children and their nurse, for her maid, etc., ad infinitum. Long distance from Hollywood, she cancelled appointments, rescheduled interviews—in short, acted like a real prima donna.

Finally Bette arrived with twenty suitcases and an entourage worthy of a real queen. It didn’t take her long to find out that the suite didn’t have connecting doors between her room and the children’s room (this was in wartime when there was a tremendous shortage of hotel rooms). It was then that Bette put on the best act of her career. She positively roasted the spinning Warner press agent. At the end of the histrionics, Bette imperiously demanded that the publicity head come to the hotel. She then went through her act again, not missing a beat, and ended with: “Why did you ever put us in this hotel?” The press agent courageously pointed out to her that she had insisted on this particular hotel. Bette was taken back for only a moment, then recovered quickly and said: “Do you have to do everything I say?”

I miss Bette in Hollywood and wish she were back with us permanently instead of just once every year or so. We can use the kind of excitement she always provides.

One of the most heartwarming performances I’ve ever been witness to was by my boy, Jerry Lewis, when he was seriously ill last year—although I didn’t know he was putting on a show at the time. He was under the weather and I called on him at his home to cheer him up. I stayed an hour and never laughed so much in my life. I’m his best audience, he told me, and I am. All he has to do is say “Hello, Sheilah,” and I break up. Lying in his bed, Jerry regaled me with story after story and even went through one of he routines he was planning for his next picture. I don’t know if my visit did him any good, but it certainly cheered me up.

The next day I called Jerry’s wife, Patti, to see how my boy was progressing. “Sheilah,” she told me, “we’re so relieved. We’ve just gotten the report from our doctor, and all the tests were negative. Jerry doesn’t have cancer.” All the time that Jerry had been joking and laughing with me the day before, the possibility that he had that dread disease was hanging over his head. But not I nor anyone else knew about it until it was all over.

Jennifer Jones won an Oscar for her first big screen performance in “Song of Bernadette,” but her performance in that picture was nothing compared to one she gave for me not long ago. I had happened to mention in my newspaper column the well-known fact that Jennifer’s husband, producer David O. Selznick, supervised her every move as far as her career was concerned, from deciding what pictures she would make with which directors and actors to what style of dresses she would wear.

The day the item appeared, I received a call from Jennifer in New York. The shy, reticent, almost recluse-like Miss Jones sounded like Kate in “The Taming of The Shrew” before she was tamed. The way her voice was pitched, Jenny could have just yelled at me from New York to Hollywood and I would have heard her. She didn’t need the phone. The gist of her remarks was, “You’re wrong, wrong, wrong. David absolutely does not supervise my career. I make all of my own decisions.” I tried to get a word in edgewise but had no success. Finally, just like in a Jack Benny radio script, I shouted: “Wait a minute! Wait a minute! Wait a minute!” That silenced her. “Jennifer,” I hollered, “I’m sorry, but let me just congratulate you on the finest performance of your career”—and I hung up.

Another scene that was beautifully played on the “Ameche” occurred with Betty Hutton in Washington. I was there attending the Annual Publishers’ Convention and Betty was appearing with her variety review in the capital. At the time she was still married to dance director Charles O’Curran, but there were rumors of an impending split-up. I called Betty to check the rumors.

“Everything is wonderful between us,” Betty cooed to me over the phone. “Sheilah, you know I wouldn’t lie to you. Why Chuck is here beside me right now and we couldn’t be happier. I don’t know how those silly rumors got started, but there’s not one bit of truth in them.” What she didn’t tell me was that O’Curran had already flown back to California and the marriage was ended.

When June Allyson was on my television show recently, the subject of off-screen performances came up while we were waiting for the signal to go on the air. I asked June if she’d ever given any worthy of note. She thought a moment, then said: “There was one, Sheilah. I don’t know if it could be called my best, but it was certainly the most difficult performance I’ve ever given, although I didn’t think of it as a performance when it was happening. It’s over two years now, and it was when Richard was so ill. Remember?” I nodded my head.

“The doctors had told me that Richard was not expected to live,” she continued. “At four o’clock this particularly bleak morning, the hospital called me and said they thought I should come over. He was very low. I was holding on to myself with a sort of steely determination, but to this day, I don’t remember how I got there.

“I do remember though, sitting at his bedside, holding his hand. I felt as though my heart would burst, but every time Richard opened his eyes I managed to smile at him and tell him everything would be all right. I wanted to run screaming from the room, begging somebody to do something for him, but I didn’t. I made myself sit there and smile. Richard told me later how much those moments meant to him, I bottled up the tears in me and kept them bottled up until he came home. Then, when I knew he was going to get well, I let go. I must have cried buckets that day. I discovered then that you can do anything if you love someone enough.”

Eleanor Parker’s best off-screen performance may result in her winning an Academy Award for her on-screen performance as Marjorie Lawrence, the famous opera singer, in M-G-M’s “Interrupted Melody”. Here’s the story behind the story.

Greer Garson was originally set for the role, but by the time the picture was ready to be made, Greer had ankled the Metro lot. Jack Cummings, who was to produce the film, was stuck for a leading lady, but he just couldn’t see Eleanor in the part of a prima donna, because off-screen, Eleanor is quiet, conservative and a devoted wife and mother to her three youngsters. But Cummings didn’t reckon with the determination of a woman who was after something she wanted—and Eleanor wanted to play Marje on the screen.

So, one sunny afternoon, Cummings was sitting behind his studio desk, slowly going over the list of possible candidates for the role, when his door burst open and in rushed a flamed-haired bunch of fury. He had to look twice before he even recognized Eleanor. She took the offensive and accused him of disliking her, said if she played the Lawrence role she would do thus and thus and then proceed to show him. She exploded into a dramatic firecracker that would have done justice to Bernhardt. Infuriated by Ellie’s attack, Cummings replied that if she played the part she would do as he told her. Then he suddenly realized she had deliberately tricked him into seeing how temperamental she really could be when she set her mind to it. As you know, Eleanor got the part, and as I said earlier, her performance in it may win her an Oscar.

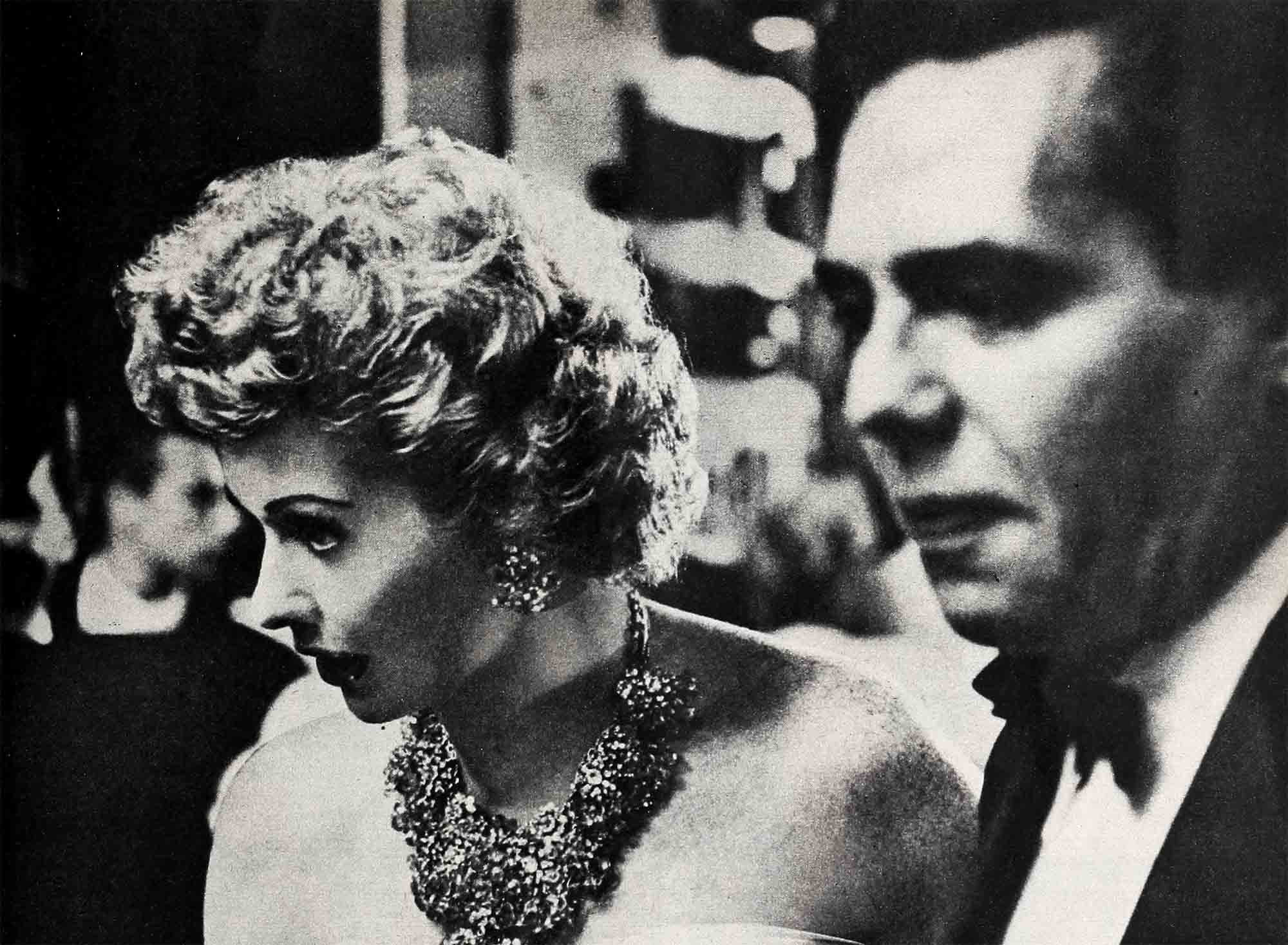

The greatest performance I ever saw Rosalind Russell give took place in a theatre—but not on the screen. It happened some years back when she attended the Academy Awards and everyone fully expected her to win an Oscar for her great performance in “Mourning Becomes Electra.” Even Roz thought she was going to win. Finally the time came to announce the winning actress.. Roz was half out of her seat before she realized the name that had been called wasn’t hers. She’d been so sure—as had everyone—but Loretta Young was winning it for her performance in “The Farmer’s Daughter.” Roz’s recovery was magnificent to behold. She sank back in her seat and, for the briefest moment, looked as though she might cry. Every eye in the theatre was on her. Then she smiled and began applauding heartily for Loretta, who is one of her dearest friends. I wanted to give Roz an Oscar for ,her performance that night.

More recently, Judy Garland matched Roz, and for the same reason, though she wasn’t in the theatre but in the Cedars of Lebanon hospital where she’d given birth to a son the day before.

I received an account of Judy’s reaction from the director of my own television show, Dick McDonough, who’d been assigned by NBC to televise Judy from her hospital bed if she won.

“She was just wonderful about it,” Dick told me. “That Oscar meant so much to her. It would have been the crowning achievement of one of the most spectacular show business comebacks in our history. I was watching her when the announcement came that.Grace Kelly had won. A look of dismay, of disappointment crossed her face, her eyes clouded up, then she smiled at us and quipped ‘You fellows certainly wasted your time and money tonight. I’m sorry, but I have my own Oscar now anyway. Then she waved cheerily to us and said: ‘I’m afraid I’m a little tired, so if you’ll excuse me, I think I’ll try to get some sleep.’ That was all, but I felt as though I’d witnessed one of the truly great performances of my life.”

Tony Curtis has been steadily improving as an actor, but I don’t think he’ll ever top the performance he gave one Saturday afternoon in Boston when he was there to make “Six Bridges to Cross.” Tony wasn’t working that day, so he kept a promise he’d made to visit a children’s hospital. He was waiting in the entrance hall for the nurse who was going to accompany him through the wards, when suddenly he was confronted by a youngster about thirteen years old. Two years before the boy had been burned from the waist up when caught in a fire, and the doctors in the hospital were completely rebuilding a new face for him. It wasn’t a pretty sight.

“He stared me right in the eye when he introduced himself to see if I flinched when I looked at him,” Tony said later. “If I had, I would have hurt him deeply, I know. My first instinct was to grimace, but I didn’t. I don’t know how I did it, but I smiled, kidded him about looking awfully healthy to be in a hospital, jokingly accused him of gold-bricking. He kidded back, and we became friends. He walked around with me through the wards. The nurse told me afterwards I’d done more for his morale than a dozen doctors could have done. When I left I felt so sorry for him I almost broke up. Thank God he never knew.”

Oh, there have been other off-screen performances too that I could tell you about, performances by Robert Mitchum, Rita Moreno, Doris Day. Take it from me, more often than not, some of the best acting hasn’t been caught by the camera—only by some person on the scene.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1955