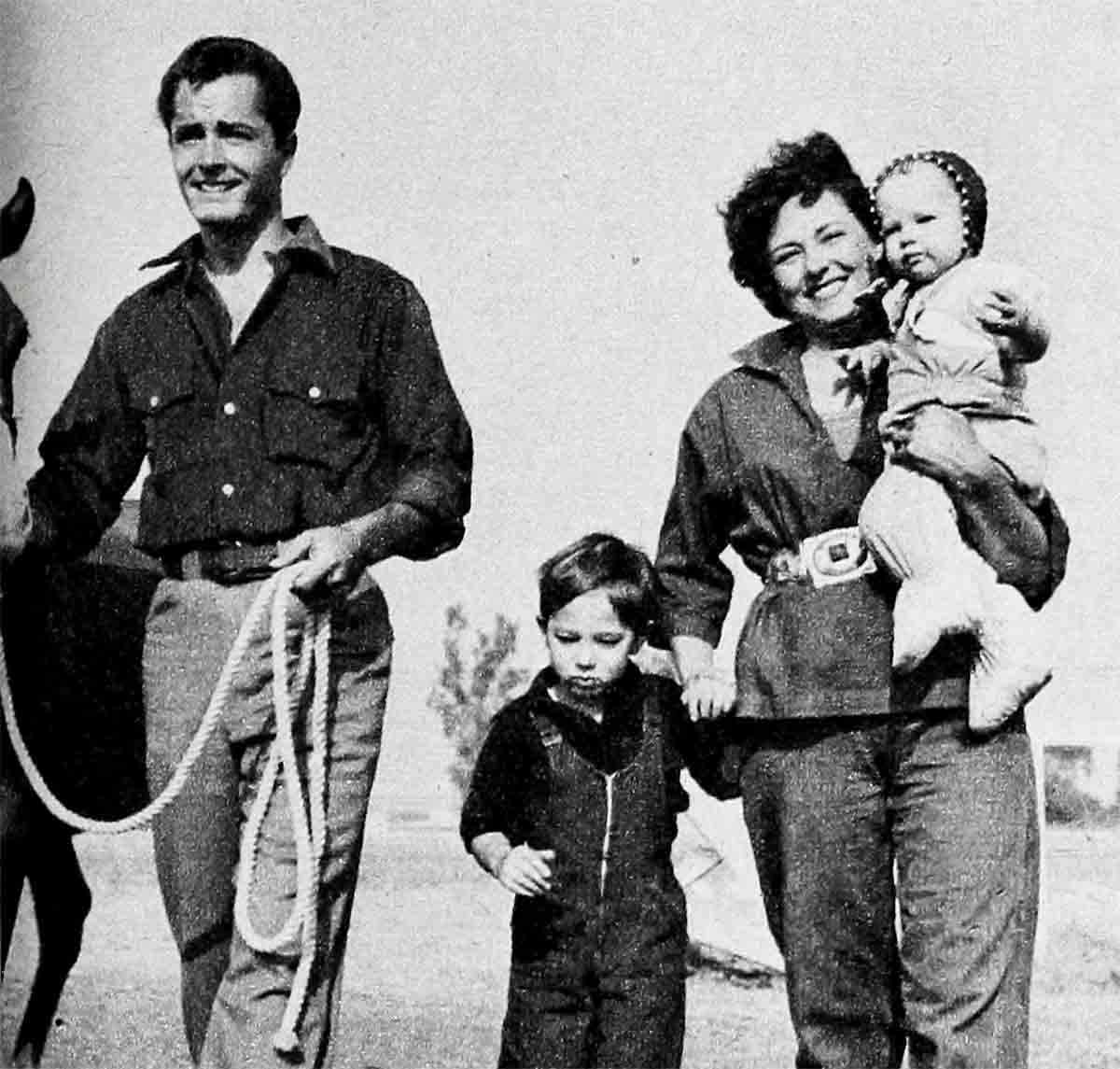

The Big Gamble—John Derek and Pati Behrs

Don’t tell John Derek the best things in life are free. And don’t tell his wife Pati either. The best things in life, they know today, you pay for. And the price can come very high. And you may pay with your heart.

You pay in dreams, still unfulfilled—which may never be fulfilled. You pay in tears—more tears than it seems possible for you to cry. In dollars—and the worry about dollars that won’t quite stretch around. You pay in words—fighting words—that can never quite be taken back. You pay in freedom. And in fear—watching a little boy’s face as the color comes and goes again and again.

Today John Derek, the handsome dashing motion-picture actor who lives in the deeper San Fernando Valley, turns a deaf ear to adventure and limits his travels to trips to the hardware store.

Today pretty and talented Pati Behrs Derek is content to forego the spotlight and the sweet sound of applause and live the life she and John have learned to value together. They both know that it’s worth sacrificing for, and fighting for and—whatever the handicaps—worth hanging onto.

As John says meaningfully, “When you’ve seen your kid die—and live again—and die and live, you look at him. And you see him. Really see him. You don’t take him for granted. Not one day. Not one hour. You take a close look—tomorrow he may not be there. Other married couples go to a window and say, ‘Isn’t he cute’—and count to see if his toes are all there. But they don’t really see him. When you’re holding him and he turns dark blue and starts to choke—you see him. He may not be around the next time. It gives you a better appreciation of what you have. And believe me, you take a good long look . . .”

Pati and John really cherish their children and their home. And why not? Pati was a refugee from war—always on the run. John as a boy was caught between parents—and between military schools. Too many military schools. When, like John, you’ve never had a solid steady home to depend on, you take a good close look at the rambling ranch house in Encino you finally call your own.

And when you’ve never belonged to anybody, you love the closeness and belonging of marriage. If your name is Pati, you take a good look at this restless adventurer, this mad impractical man who is your husband and who, despite his infuriating moments, loves you very, very much. If you are John—and you have been lonely too many of your twenty-eight years—you look at this pretty, pert, practical and equally infuriating little package—whose warmth and spirit and fire and loyalty and love matches your own. A girl who will never let you be lonely again. You look at each other. Really look, and you know what you’ve found finally—together. And you know no matter how stormy the weather you’ll hang on.

They’re Hollywood’s strongest, and frequently stormiest love story—John and Pati Derek. And theirs is a story that began with a gamble.

Outside that chapel in Las Vegas six years ago, the “strip” glittered and beckoned. Wary-eyed croupiers called the last throw and turned the next card.

Inside the chapel two beautiful people with dreams diluted by disillusionment were gambling for higher stakes. The rest of their lives together. Against odds greater than even they could know.

They couldn’t know then, promising to take each other for better and for worse, for richer and for poorer, in sickness and in health, they would be challenged all the way, that they would have an overwhelming lot of happiness and along with it tribulations, too.

Even if they had known, together they would still have defied Fate to turn her next challenging card. Challenge, in whatever form, had long been, to each of them, both friend and enemy.

Each was born to a plush heritage. The bride with the piquant face and doe-brown eyes was a Georgian princess whose family was forced to flee to Turkey when their estates were taken over by the Communists. As a child she worked in pictures in France. At thirteen she was dancing in a French cafe. Her twinkling feet were star-bound with the ballet. When 20th Century-Fox discovered her and sent her to Hollywood, Pati Behrs was determined to make a name and an identity for herself in this new land. Then she met a handsome lad whose heritage and determination in many ways matched her own. Nor was war a stranger to him. A paratrooper just back from combat duty in the Philippines—and from occupying Japan following the atom bomb—he was sober beyond his twenty-one years.

Derek Harris was born into a kingdom of celluloid. The plush Hollywood of the 24-carat scrapbooks and white Russian wolfhounds strolling Sunset Boulevard. His mother, a beautiful actress of the silent screen; his father, a promoter-producer-actor. He grew up alternately in luxury and comparative poverty. Home was a cottage or a mansion in the Riviera Estates. One year he might have a thoroughbred horse of his own and a chauffeur to drive him to school. Another year, the mansion and horse were gone. But most important, his family was gone. He began growing up at the age of five, when a child’s safe warm world collapsed around him. His parents separated and a sensitive emotional kid was torn between the two.

As he grew older, Derek’s dream, like Pati’s, was to make a name and an identity for himself which would last. Hollywood was his home town. Its blazing marquees and lights arcing the skies were as familiar to him as the streetlight on the corner of any small-town square. But he grew up expecting no magic from the make-believe. He’d seen too many hopeful citizens come and go. Nor had he known any roots here. Nor security. He was ever on the run, until one day when he opened a door on the studio lot and met a lovely girl in a green corduroy suit. A girl both enchanting and earthy. A girl of character and decision. No frills, no fuss, no giggles. A girl who turned down his first proposal—until they knew each other better—then when another seemed too long forthcoming said frankly, “I think it’s time to ask me again.”

John Derek became a star overnight in “Knock on Any Door,” and this opened the door to their future, to marriage, a family, and the first real home either he or his wife had ever known. But they had long ago learned, John and Pati, that in this life you open your own doors. And they continued their search for security hand in hand.

During the six full years since, Fate’s thrown her whole book at them. Challenge and situations have faced them which would have defeated two less in love or less strong.

Theirs have been the constant clashes of two strong wills and trigger-temperaments, of two who have finally made an identity and are dedicated to preserving that identity. Almost overnight John was the screen heartbreaker and a popular boxoffice star. Almost overnight a lovely girl, who was also star-bound, was dredged in domesticity. Half of Pati’s identity merged with John’s.

These have been frustrating years for John. He had a feverish dedication to be the actor he felt he could be. There was Pati’s illness during her first pregnancy, months when she was confined to bed. John, all thumbs, helped keep the homestead running. There were bills. And more bills. As he says, “Money means nothing to me.”

There was the near-tragedy of their first-born. The strain they’ve shared of months and years helping their boy hold onto life. Of sleeping, eating, living with one eye ever upon him, lest he still slip away.

There was the year and a half when John didn’t work before the cameras. Then John’s decision to freelance realized amid life’s worst timing—with little money in the bank and another baby on the way.

“I’d beefed so much about getting free from the studio, I couldn’t say, ‘Look, fellows, let’s wait just a little longer now,’ ” John says.

But theirs is a marriage with muscles. Life has never been lukewarm for either of them. Nor would they like it lukewarm. On occasion their marriage has been a survival of the fightingest. But strength they each demand. Weakness neither could stomach or understand. They match—word for word, spirit for spirit, and heart for heart.

Theirs, too, is a shared honesty of emotion which each preserves conscientiously.

A writer arrived at the new Derek hacienda recently to do a tender and tranquil story on the John Dereks and found them in the midst of a domestic impasse. Their baby, Sean, was crying in rebellion against the two-o’clock nap. Russ was hammering and playing carpenter. The traffic was thick with other carpenters, also painters and plumbers. John had just invited Pati to “furnish the house yourself, then.” To arrive at any decision, he said, was better than no decision at all. Although whose decision was still in doubt. They sat there, weary and wary. Pati in a yellow sweater, blue jeans and tennis shoes was curled up in one corner of the room. John, with his feet crossed and his shirttail out for comfort, in another. Both eyed vigilantly the space in front of the copper fireplace where a disputed coffee table would go or not go. John had designed a spectacular four-foot glass table with the wagon wheel of an old prairie schooner for the base. Pati argued that when the children fell over the table, the metal base would be harder than wood.

“But it’s not a sharp edge, it’s a rounded edge. Besides, we can’t pad the whole house!”

“You can cover the wheel with rawhide.”

“Rawhide! That’s just as hard. And they didn’t use rawhide on wagon wheels in that time.”

More silence. Finally the writer got in a question. “About their romance—how did they fall in love?”

“She didn’t giggle. That was the year all the Doe were giggling. Now she giggles.” John glared at Pati, who was doing anything but.

“He was so kind and gentle,” Pati said, for her part.

The writer departed for a more tender and tranquil time.

Which, with John and Pati, occurs just as immediately. For all John’s speeches, he will, of course, put leather around the wagon wheel—“if there’s any danger.”

And the whole incident of the coffee table is forgotten in joint jubilation that the new powder room will cost a few dollars less than they’d expected.

Familiar scene this—to young modern marrieds from Keokuk to Kalamazoo—and Hollywood, bent on building a home and a marriage.

John’s artistry clashes every now and then with Pati’s practicality. “I’m not as practical as most people are,” he admits. “I get myself up blind alleys a lot of the time. Nothing major, just blind. But the practical usually isn’t any fun. And besides I don’t have to be. I have people being practical for me. Like my wife.”

John has, for instance, always leaned toward modern furniture. Pati loves Early American. The last house was modern up-stairs, with the downstairs Early American. But this redwood modern ranch house with it’s enormous richly paneled living room and the thick beamed ceilings cries, John believes, for massive ranch modern.

“The furniture should have thick legs to match the beams,” he says.

Pati agrees the other furniture has got to go, but . . . “But I don’t think the furniture should be that heavy—so heavy it takes two people to move it.”

“You can’t move the old furniture by yourself, either. Maybe on a slippery floor, sliding it along. You couldn’t push it on a rug,” John insists.

The unfortunate mention of a rug reminds Pati that being practical can have its advantages. Such as that time she helped John get the thoroughbred he wanted by talking the price down.

“You wanted a rug.”

“Did I get my rug?”

“No,” John admits honestly, “but you will.”

Not that money is too much of a domestic issue. “John is very generous,” says Pati.

John puts it this way, “I like pretty things. And pretty things you have to pay for. You can get ugly things for nothing. But I like pretty things, unfortunately. Like Pati,” he grins.

The good things of life you pay for, too.

And safe inside their own hacienda like other young marrieds who live so close and so constant John and Pati occasionally ruminate on marriage. They discuss its virtues and vicissitudes. And discuss whether or not they’re paying too much of themselves for their shared happiness. John sometimes hears planes singing overhead, or the imaginary whistles of freighters bound for adventure. And there are times, when the baby’s crying, dinner’s cooking, Pati doubtless remembers a talented girl whirling on her toes to the swell of music and applause.

John may philosophize, “Marriage is like drawing up plans for a house. It looks better on paper.”

Or Pati may decide, “You give too many ultimatums. Either this or I can go ahead and furnish the house by myself. Either that or you will go.”

“So I haven’t gone,” John reminds her. “And I don’t give ultimatums,” he protests. “When a sergeant gives an order, that’s an ultimatum. If I did what I say I’ll do, that would be different. Mine’s just fine conversation. Have I ever packed a bag?”

Whereupon Pati says laughingly that if either of them could calmly pack a bag, that would mean there was a good understanding. That would be good. “But a better way, I think, would be to run away and call back in a couple of days when you cool down.”

“Two days—and call back!” says John, paling a little at the thought. “When I ride horses and don’t call for three hours—well! Two days—I’m not coming back.”

More fine conversation. They both know.

And why is the bag never packed? “I wouldn’t like Pati to be unhappy,” says John. “I’d worry about her. I’m weak that way,” he grins.

He’s also weak when it comes to compromising. “Like this house. I wanted a ranch,” he says.

“In Phoenix,” protests Pati. “He wanted to move to Arizona.”

For all the talk he does about traveling, John is now a home-lover. “He won’t take a vacation alone because he would worry about the whole family,” Pati says. Today, instead, this armchair adventurer settles for a living-room safari with Russ on his lap, watching “Ramar of the Jungle” on TV.

John admits it’s a project to get him off the homestead for a dinner party or a night on the town. “When it comes to that, I balk. I like people in small groups sitting around our living room or theirs. Friends. But crowd-hopping—from club to club—the same crowd with nothing in common and a lot of phony conversation—that’s not for me. A safari to South America—or even to Santa Anita—that’s something else.”

Not for these two the routine problems of some movie marriages. Not for John, any heavy-handed husbandly bit about Pati never returning to her career.

“John wouldn’t tell me not to, or interfere at all,” Pati says. But if she did, with his pride in her, John wouldn’t want her to be half a success.

Nor does jealousy menace this handsome pair. “I used to be jealous,” Pati says, “but what good does it do?” Furthermore there’s small need. John’s artistic eye is caught by the contours of a coffee table, rather than more provocative subject matter.

According to her husband, he’s no target for the glamour girls anyway. “You’re not exposed to many, not in our crowd,” says John. “And at the studio you work mostly with the same group of girls in every picture. All of them have known me for a long time.” Not that John is insensitive to beauty. “I know it’s there,” he says. “I don’t find a pretty girl unattractive. Just unavailable. I’m married.” And besides he wouldn’t want to worry Pati. He’s weak that way, too.

Gossip columns would have no success separating them. “Pati soon caught on to that,” John says. “When columnists itemed me as being in places I’d never been, with people I’d never even met, when she knew I was home looking at television with her, they don’t bother her.”

Theirs is an active partnership in every department. Each is intensely interested in any project which concerns the other. Even as John’s artistic eye is caught by every detail of homemaking, Pati’s absorbed in all the facets of John’s career. “Pati spells the profession and it’s problems,” John says. And he’s quick to acknowledge her encouragement during tough sledding, and when he decided to freelance and not re-sign with Columbia.

“Everybody else was saying I was wrong, but Pati went along with me,” John says. “It was hard to believe I was right, but she did. Although not as much as I did. She was a little spooky about it.”

Pati shares his happiness that the big gamble has paid off. That John’s getting cream roles under his new exclusive contract with Paramount, leading off with the very challenging characterization of the embittered cripple in “Run for Cover,” in which he co-stars with James Cagney. “The roles are reversed,” John says, “I’m playing a Cagney part.” Paramount loaned him to 20th Century-Fox for the role of John Wilkes Booth in “Prince of Players.” “That’s the best thing I’ve had so far,” is John’s comment. And now comes the role of Joshua in Cecil B. de Mille’s “Ten Commandments.”

John is touchingly indebted to de Mille, saying, “He was interested in me when nobody cared.” And there will always be a special place in Pati’s heart for de Mille, too, for giving her husband faith and a boost when he needed it most. Yet a typical misunderstanding happened the night John came home from his triumphant interview with de Mille—walking on air and feeling ten feet tall. He found Pati in the kitchen, and reported glowingly that Mr. de Mille thought he had a very promising future in the business. He was hurt and furious when Pati said, “I’ve always known that. I knew it all the time,” as though she were breezing it off.

“When I told her, she was working in the kitchen with her head in the sink. And she didn’t even take her head out of the sink. That made me mad,” he recalls.

“You misinterpreted me,” Pati explains. She was hurt, too. “John underestimates me. He pays no attention to what I say. My word doesn’t mean anything until somebody else says the same thing.”

John is very sensitive where Pati’s opinions are concerned. Let them disagree on the reading of one line and the professional fur fairly flies.

“You give me no credit for knowing anything,” Pati will say at such times. “Even when I compliment you, you won’t believe me. I was an actress in the business, too, remember?”

“Well, in a round-about-way. You danced,” her husband says.

“I suppose ‘The Dying Swan’ is just fooling around. And I was acting in France when I was six years old!”

“Who can act at six years old?”

“For some people acting is nothing. You won’t take my opinion on anything!”

“Yes I will.”

“On what?”

“On ballet,” her husband grins.

On occasion, when they have differences, John will say finally, “Oh, Doll, everything would be just great if only you would agree with me. If you would say ‘Yes’ half the time. Or if you must say, ‘No,’ if you’d only say it more gracefully.”

But in spite of John’s making noises like a husband and intimating he’d like to be “Yessed,” Pati has grounds for doubt here, too. “If I agree with him, or if I tell him he is very good, then he doesn’t believe me at all. ‘You’re just not interested,’ he says. I’m so interested, as much as if I’m making the picture.”

As John says, “When you love somebody—every word counts twice. And you’re twice as sensitive.”

And, as anybody who knows the Dereks knows, while honesty may not always be a peaceful policy, it amounts to a religion between them. What he wants and gets from Pati is the truth. He wants no hocus-pocus, no false flattery, no buttering up the ego.

And when it comes to an undiluted exchange of opinion, they admit they’re reasonably consistent. They will, as John says, argue about practically anything. “And afterward we can’t ever even remember what the fight started about,” Pati says.

They shared some concern about having any differences in front of the children until Pati’s doctor ruled, “It’s all right to argue in front of the children if you make up in front of the children also.” The doctor “says it’s perfectly normal for parents to argue.”

Nor is it fatal for parents as long as they make up.

Ask John what he considers Pati’s most admirable trait and he says readily, “Her guts. She has so much intestinal fortitude. Sure, I may argue with it. But that doesn’t mean I don’t admire it. Pati will always stand up for herself—and for me, I hope.”

Ask Pati what she most admires about John and she says, “The main thing is that he can have such courage. He’s so definite in his beliefs. When John feels anything, he’s not afraid to say it. Sure we have differences of opinion. What couple doesn’t? If we agree on everything, as from one source, then why be married? It would be like living with yourself. And the closest ones are always the most critical. It’s better to blow up and get it all out of your system.”

On this they are agreed. Better to be frank than to bottle up emotions and explode in a divorce court. And peace at any price is no good. “Deceit doesn’t last,” says John. “It bogs down and it’s not a marriage anymore.”

He, too, shrugs off their differences of opinion somewhat philosophically. “That’s marriage,” he says, “when any couple are together as much as we are. Any two people who spend this much time together will argue. We’re together more than most married couples. The average businessman is away from home all day. On Saturdays and Sundays they go somewhere or visit friends. But we’re together constantly.”

No doubt about it. They’re thoroughly hooked, these two. And they love it. Every loving, fighting moment of it. And in the clinches—that’s right where they are. The clinches. They’re both weak that way.

Together—they’re finding security.

The kid who never had a home or really belonged to anybody and who was determined to make his own name is today prince of a celluloid world with loyal subjects all over the globe. Pati, a princess in blue jeans, ruling right where she belongs, beside him.

Their own kingdom commands a gentle rise which looks towards changing vistas—purpling mountains, a green carpeted valley and twinkling lights. Their immediate and loving subjects number two horses, two huge German Shepherd dogs. As John says, “If the two dogs were cut up they would make about fifteen small dogs.”

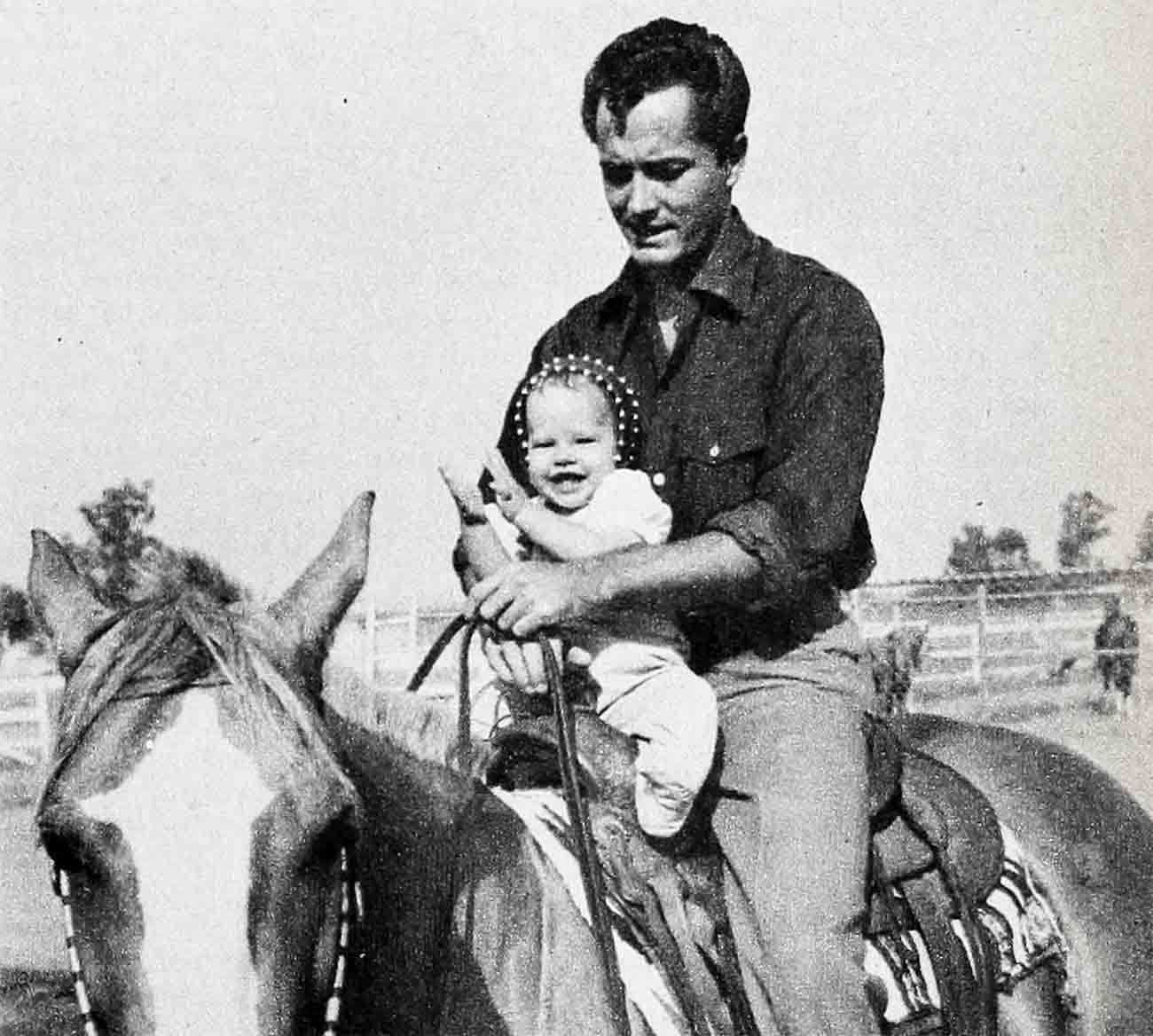

Their baby daughter, Sean Catherine, is queen of the whole works. “We’d decided if the baby was a boy, we’d name him Sean,” John says. Somebody suggested it—and I’ve got a little bit of Irish in me, enough to make it legitimate. And Id used up my best friend’s name on Russ. Sean,” John says, “Somebody suggested it cute for a girl, too. Depending on the girl of course. If she’s pretty and cute, which she is. She’s a little doll.” Quite an admission from a man who once held the opinion that all babies should be born at least two years old. Today he’s the first to protest to Sean’s mother, “She’s not spoiled.”

And young Russ is the most important thing in all the world to both of them. A delicate child with his dad’s sweeping lashes and coloring. At the moment, a busy little boy making like a carpenter in a plaid robe and red boots and wearing a straw hat with a big marshal’s star on it. “It’s my carpenter hat,” he maintains firmly.

He’d just had his tonsils out two days before. “Looks a little pale, but good. Just sitting up—he looks good,” his father says slowly, watching him. “Russ had really had it. All of it. Rheumatic fever. Strep throat. Now his tonsils out.” Born with a separation in his esophagus, with rare and successful surgery and constant vigilance, Russ survived his infant years. His throat passage is smaller, and there’s half an inch there with no feeling. No nerves. Explaining their constant concern, Pati says, “He’s just a little boy. A piece of food he doesn’t chew well gets stuck in his throat and he can’t breathe. When he gets older he will be able to take care of himself and eat anything. We can talk to him and make him understand. But you can’t explain to a very little boy. When he was a baby, they could put his head back and let air get into his lungs. Now they call the fire department and the inhalator squad.

With his love and concern for Pati, John may protest about her being too concerned about the children. “She confines herself too close to home,” he says. “We could have ten nurses and she wouldn’t leave. She’s a great little mother, but I think ninety per cent of the time she is over-concerned. Other families have sick kids and the mother gets away. Pati won’t leave the house, not even for one night.”

But such minor disputes are of no moment against their many shared poignant memories. Memories that make a marriage. Those first months of Russ’ life when Pati never slept—and literally willed their son to live. Whimsical memories, for her, like the IOU’s John gave her for Christmas that couldn’t be cashed until he worked again. The time John forgot her birthday—and how he could forget a birthday right between Lincoln’s Birthday and Valentine’s Day—she couldn’t understand. “Nobody could forget that—February 13th,” she’d wailed. The pound of fudge he brought home later. “We were broke at that time.”

They’ve made their six years of marriage the hard way. But they shrug this away. And they have no truck with other marrieds who indulge in self-pity or dramatize “happiness” too much. “Too many people kick the word ‘happiness’ around too much. Worrying about whether they’re happy or not,” John believes. “Marriage is mostly companionship and children. You get married. You make a home. You have a family. There are some peak moments—special times when you’re getting along and laughing it up, when you’re not arguing, when money is easier.” John’s grateful for the first tough years of his life. “When your parents separate, you know you don’t have a family to lean on. You know you must depend on yourself. It toughens you to take life. It’s an education a lot of kids don’t get until they’re men forty years old. It’s an indoctrination for life. And I got it young. Pati has matured more than I have,” John says frankly. “We haven’t really settled down yet. Not like couples who’ve been married ten or fifteen years.”

Both of them believe the worst is behind them, and the best ahead. “It should go easier now,” says John. “Russ will be going to school this year and Pati won’t be so confined. She can divorce herself more from home and the family. Get away more. And that will be good. Our arguments won’t mean so much to her. The little things won’t seem so important.”

As for their first six years together, they both agree they’d stack them up against most of the other marriages they’ve observed firsthand. And well they can.

If forced to, John and Pati Derek would do it all over again. They are, admittedly, weak that way.

Together they’ve made a place for themselves in both worlds—the dream world and the real world. Together they’ve found their blessings outweigh the occasional bedlam. As for the din—that’s marriage. The melody of love.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1955