What Debbie Reynolds Can’t Forget?

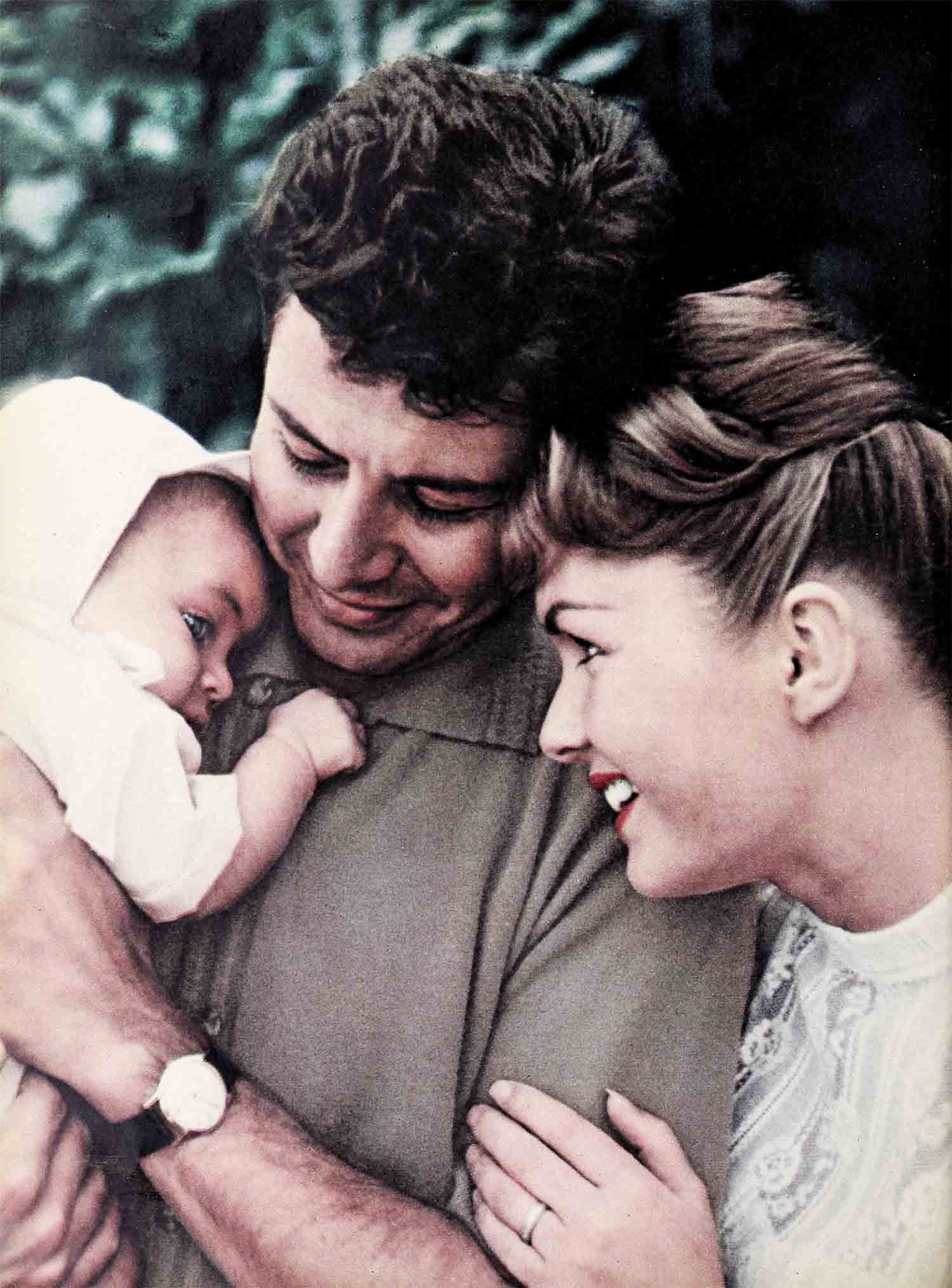

Debbie Reynolds sat alone in the big chair. A few months ago, she had sat there with Eddie and both their babies—it was a family-size chair, built to hold all four of them. They had turned off the lamps to let the firelight glow on the bright prints and warm colors of the room. She and Eddie had designed the room for family living; they had talked and planned and compared all the swatches of fabric and pictures of furnishings she’d collected on enthusiastic shopping trips. And they’d seen the room grow out of plans into reality around them.

Across the room that evening had been Debbie’s mother and father, on the sofa they favored each time they came for a visit. No matter how often that was, their proud smiles showed that they couldn’t get over the wonder of Debbie as wife and mother. They had watched her in the big chair, cuddling little Todd on her lap, her other arm around Eddie, who had one arm around her and the other around Carrie, who reached out herarms to baby brother.

“Look at you kids,” Mrs. Reynolds had chuckled fondly, “all tangled up! How are you going to get out of there?”

Debbie had laughed, “There’s no other way to sit in this chair. That’s why we bought it . . .”

Now, on this cold night, she was learning another way to sit in the chair—alone. It wasn’t comfortable. It felt big and empty—the way the whole house felt without Eddie. Empty and lonely. The room they had done so carefully in white and rose, for warmth, for gaiety, was suddenly cold and quiet. So quiet she could almost hear Liz Taylor’s voice out of the more distant past, the first time Debbie and Eddie had asked the Mike Todds to their new home for dinner. After the guests had been led all over the house on an inspection tour, Liz had stood by this hearthside, and she had said, “So cheerful, Debbie—it’s such a happy room. It looks like you.”

And Debbie’s own voice had answered: “I am happy.”

That had been true, Debbie thought, as the remembered voices echoed and faded. True then—even more true in the months that followed their move into the new house. The months had brought their second baby, brought evenings so serene that Debbie could say even now, with all her heart, to all who would listen: “We’d never been happier than we were last year.”

Could enough have happened in so short a time to turn happiness into nothing but a memory? What had happened?

Sitting alone in the big empty chair, Debbie Reynolds began to remember. There had been little else for her to do since the awful day when, suddenly, Eddie had left her.

Was it only a year ago that she had shown Liz and Mike proudly through her new home? Only a year ago?

What had been in their voices then? Was there something hidden in Liz’ tone? Some—jealousy? Debbie shifted in the big, tweedy chair, tucking one leg under her. No, it wasn’t possible. How could there have been anything? When Mike was alive, Liz didn’t seem to know there was another man on the globe—and especially not Eddie, not Mike’s best friend.

Why, she could remember when Liz had called Eddie to her house. She and Mike had had a fight and she needed someone to talk to, someone with a shoulder for her to weep on. Mike had stormed out in a fury but he phoned Liz while Eddie was still there. Eddie had sneaked out without her even noticing. “Mike growled something about Liz being with another man,” Eddie had told her, “but Liz explained that it was only me. The next second, she was laughing and crying into the phone. I guess neither of them needed me,” Eddie had said, and there’d been a sheepish grin on his face. They’d laughed together over what wonderful, zany people the Mike Todds were . . .

Could Mike have guessed at anything? Big wonderful Mike, so much in love with Liz that he wanted to shout it from every front page. Mike was shrewd. If there’d been anything to guess at, anything to suspect, surely Mike would have known.

Debbie sighed. There must have been something in Liz’ voice that day, something that she, and maybe not even Mike, had not been clever enough to hear. How else could Liz have said later, said for all the world to hear: “I don’t feel I’m taking Eddie away from Debbie because she never really had him. He’s not in love and he never has been.”

Had Liz believed that back in the old days, too? Had everyone in the world believed it, known it—everyone but herself?

“I’m so happy,” she had said. “I’ve never been so happy in all my life.”

All the while her world was crumbling down around her, she’d gone on being happy. Even when the newspaper stories began to come out of New York, even then she hadn’t guessed. “I won’t even dignify them with a comment,” she’d said out of a loving, trusting heart. “Eddie and Liz are very good friends. What’s the matter with a friend taking a friend out in the evening?”

She’d meant it, too. She’d meant it so much that even after Eddie had let her go ahead at six-thirty to meet the morning plane he wasn’t on—even then she didn’t dream what it really meant. He hadn’t bothered to let her know that he was staying on in New York, and she’d been furious. She’d managed a smile for the reporters and for an old friend, Peter Lawford, who was on the plane. “I’m here to meet you,” she’d told him. A few hours later, when Eddie had called, she’d accepted his explanation: He had asked a friend to call her and the friend had forgotten . . . or couldn’t reach her . . . or something . . . Whatever the story was. it was her husband’s story and that made it all right. She’d scolded him for not calling himself, and then she tried to forget it. I’m being a good wife, an understanding wife, she congratulated herself.

Abruptly, Debbie stood up and walked a few steps away from the chair. She fiddled with the long pigtail into which she’d twisted her hair. Fretfully, impatiently, she searched the bright, cheerful room. Then she went over to sit on the sofa, the sofa from which her parents had always looked so fondly at the picture of the happy Fisher family. Funny, thought, I don’t think I’ve ever sat here before. Eddie and I always sat in the big chair.

Thinking back, she just couldn’t believe it. No, it wasn’t believable that she could have gone on being a “good wife” when the nearest man on the street could have told her that she no longer had a husband. What hurt was that Eddie had taken Liz to Grossinger’s. There, where Eddie felt more at home than anywhere else in the world, they’d been married. There, just three short years ago, they’d had their honeymoon and she’d fallen more and more in love, something she hadn’t thought possible during their long engagement.

Even when Eddie took Liz to Grossinger’s, she’d told herself that there was nothing really wrong. Nothing between Eddie and Liz, that is. Eddie had worshipped Mike Todd and tried to be as worldly as he had been. It was another phase, she’d told herself, like buying the most expensive car he could find or like wasting all that money on his clothes-craze. Eddie, trying to be worldly, had put his foot in his mouth and she was simply impatient for him to take it out—fast.

“You should know better,” she’d shouted at him when he finally came home at eight in the morning. “It doesn’t look good to behave that way. What’s the matter with you, anyway?” She was angry, furious, in fact. She didn’t like those newspaper stories, but she still didn’t think there was a word of truth in them.

The sun streamed in through the big picture window and the lawn and shrubbery outside seemed to vibrate with its reflection. She could no longer see where the reporters had trampled the lawn that morning, taking down every word she’d shouted at Eddie. If she had any doubts about what she’d thought and said that morning, all she had to do was to check against a copy of any paper in the country that had come out that day. There she was, in pigtails and Capri pants, telling off her husband for being a dope. She hadn’t said a word, nor had a thought, about his falling for another woman. Yet next to her picture the papers had run one of Liz. Liz had known there’d be photographers and she had dressed for them, in a smart, panelled-back Paris dress. She compared the two pictures. “She’s prettier than I am,” she thought. “She’s prettier . . .”

“You ought to dress up more,” Eddie had always told her. Would things have been different if she’d listened. She had lots of time now to think about that. If she’d really been a “good wife,” she wondered now, would she have known better what kind of woman Eddie really wanted her to be?

Debbie began to pace. She went to the window to open it a bit, and the breeze that came through set the crystals dangling on the candle holders to tinkling. “Such a happy room,” she heard Liz say again. She perched on the brick window seat and turned her back on the room.

“I’m very much in love with my husband.” That’s what she’d told the reporters when Eddie had moved out. “I hope this separation will clear the air and everything will be all right.” She hadn’t even packed a suitcase for him to take to Joey Foreman’s—she’d been so sure he’d coming back before he needed a change of shirts. Or maybe he’d come back for a shirt, and they’d start to laugh together the way they had that afternoon when Eddie had to boost her over a wall, her pigtails flying, so that they could avoid the reporters and get to a car and drive to a doctor. All of a sudden, in the middle of their arguing, she’d felt her stomach begin to do somersaults. “This is no way to handle a nervous woman,” she’d gasped to Eddie as she jumped down on the other side of the wall. “Who, you?” he’d laughed. “You haven’t got a nerve in your body.”

For a moment, as they laughed together, she’d felt so good that she almost didn’t need the doctor or the pills after all . . .

But had been only a moment. That evening, despite the laughter and despite the lima bean soup Debbie made for supper, Eddie moved out. And the next day, she could no longer let herself go on thinking it would all blow over.

Because Eddie made his statement to the press.

“In answer to many questions,” it read, “I feel I should say this. Debbie and I tried very hard to make our marriage work. We have been having problems for a long time. Debbie especially has done everything possible to make our marriage succeed.

“I alone accept full responsibility for its failure. Our marriage would have come to an end even if I had never known Elizabeth Taylor. The breakup was inevitable.

“Although I have moved out of my home, I hope to see my children as often as possible. I have confidence that Debbie understands and that our friendly relations will continue.

“My personal plans for the future are to concentrate on my work and solve my personal problems with deepest consideration for all concerned.”

She read it in the evening papers.

Even now, months later, just remembering it could make her stomach contract painfully—the way it had that day. As if the words were fists, pounding against her. As if she had been struck, over and over again, till there was no breath left, and no tears. “I don’t understand,” she had said over and over again. “I don’t understand . . .”

The next day, the papers were all very sympathetic. They criticized Eddie for making a statement of any kind. “As I understand the ground rules,” one columnist wrote, “for these kind of public statements, they are always made by the lady, no matter who is leaving whom.” But when she was shown the article, she only shook her head numbly. “Eddie had to say it. I guess it was the only way to let me know . . .”

She was surrounded by friends by then. Her mother was there, taking over the house. Her girl friends were there, trying to make her rest. For one ghastly moment, the fuss reminded her of nothing so much as Liz Taylor’s house after the tragedy of Mike’s death—the crowds of friends, the hushed voices, the urging to go to bed, take a pill, try to sleep. Only Liz wasn’t there, the way she had been at the Todd house. Liz wasn’t even answering her phone

And she wasn’t Liz.

“I’m not staying in here,” she told her mother with sudden determination. “I’m taking Carrie out for the day.” She got up, braided her hair into one hasty pigtail, put on Capri pants and a blouse.

“Debbie, there are reporters out there!”

“I’m not scared of reporters.”

She wasn’t, either. She talked to them then and later, too, when she drove a sleepy Carrie home from Marge and Gower Champions’ home. She said for them the hardest words any woman is ever called upon to say: “This separation was not my idea. I still love my husband. I want him back. I—thought we were happy together.”

She even managed to smile.

But by the next day, when Eddie’s lawyer suggested that divorce talks might as well begin, when the papers were full of quotes from Eddie’s friends about how he hoped to marry Liz, how he might even fly to Mexico to be free of Debbie faster—by then she was too ill to smile any more, too ill to appear on the charity show where she and Eddie had been scheduled to sing—and too ill even to care.

But that was a long time ago.

That was in the first moments of shock, in the first agony of loss.

Now she was physically well again.

Now she was learning to sit in the chair alone.

And in those long, lonely hours with the empty house echoing around her, she did two things.

She read and re-read Eddie’s statement to the press.

And she thought.

“We tried very had to make our marriage work,” Eddie had said. “I alone accept the failure . . .”

“Very generous of him,” the press had sneered, “to admit it. Obviously it was all his fault.”

And yet—

Was it possible that it had been generous of Eddie. Was it possible this was his way of trying to make up for the mess in the papers, for the childish, scandalous way he had gone about ending their marriage? Was it even vaguely possible that if things had been different, Eddie might have had something to say in his own defense? Troubled, she wondered.

“We’ve had problems for a long time,” Eddie had said.

If a wife is too happy to notice that there are problems, Debbie accused herself, she can’t be very good at solving them. If a woman doesn’t see that her husband isn’t in love, she thought bitterly, she can’t be doing a very good job of making him happy.

And especially if a marriage has come close to the rocks before—as their’s did a year before Eddie started dating Liz—has a woman any right to be so happy that she’s blind to new danger spots?

hen the hurt was brand new, those thoughts didn’t come. Only pain and loneliness and anger. But now that a little time had gone by—now there was no way to keep the thoughts away. Sooner or later, she had to turn around and face the empty room—and the empty chair. She did it now, walking over hesitatingly, and then sitting down in it again.

She had been a good wife, she thought, but by whose standards? Eddie’s—or her own?

Take, for instance, the matter of money.

Money, to Eddie, was for spending. Money, to Debbie, was for saving. “I don’t see how you can throw it around like this,” she had protested, when Eddie came home from one of his beloved poker games with Sinatra and Dean Martin and Tony Curtis. “Why, you could practically put Carrie through college on what you lost tonight.”

Eddie’s eyes had darkened. “Don’t exaggerate; it wouldn’t pay for a semester. Besides, there’s plenty of money in the bank for Carrie’s education, even if she wants a Ph.D.”

“Well, there won’t be if you go on like this!”

She had been mad as blazes—she couldn’t understand it. Neither she nor Eddie had come from rich people. Why couldn’t he see, as she did, how important it was to have security? To know that no matter what happened, your children were taken care of. But Eddie had wanted trips and clothes, poker games and nightclubs.

It was funny that now, now that it no longer mattered, she could think of a dozen reasons why these things were so important to him.

Because the money enabled him to “buy into” those hours with the boys—hours of being a man among men, smoking and drinking, playing cards and telling stories. And because he was Eddie Fisher and the other men were stars, it cost a lot. If they had all been truck drivers—fifteen bucks would have taken care of his losses, and it wouldn’t have mattered as he sat with a beer and a salami sandwich in somebody’s kitchen. It was just—well, there were no penny-ante games for Eddie Fisher to play.

Or maybe because his career hadn’t been doing so well since his marriage—and hers had been skyrocketing so. Maybe that was why he had to spend—to prove to himself and the world that he wasn’t worried about tomorrow—that next year he’d still be making a million. Maybe if he started to skimp, people would say, “Fisher’s on his way down, all right . . .”

Or maybe just because he had been poor and now he was rich. Now he wanted to have all the things he hadn’t had as a kid. Lots of people who had been poor felt that way when they came into money. You could call it silly if you wanted to—or even immature. But you couldn’t understand it, could you?

Unless maybe you were a wife who worried about her family’s future and their security and their needs. And maybe forgot to worry about what one member of the family, her husband, needed right now.

Was it—possible?

And the business of living, just living. After they came so close to disaster a year ago, when she’d complained about Eddie’s pals “cluttering up” the house all the time . . . after “Tammy” being such a hit when Eddie hadn’t had a top record in ages . . . when they weathered that, she was so positive she knew how to make sure it never happened again. Everyone agreed with her that two stars in one family made for an impossible situation—especially when they were both doing the same kind of work. So she made a sacrifice without a moment’s hesitation: she would give up her career. She would have another baby, she would find them a house they could be happy in, instead of a palace in which they rattled around. She would make a home like her parents’ home, where the husband was the big man, and the wife lived for his success.

She would be the wife and mother—Eddie would be the star.

There was only one thing, she saw now, that she forgot to take into account as she plunged into her new life.

Eddie Fisher liked being married to a movie star.

He liked glitter and excitement, he liked opening nights. He liked to go to premieres with a beautiful woman on his arm, a woman dressed in a Paris original, turning heads everywhere. He liked to be recognized on the street, mobbed, made much of.

And he wanted his wife to like it, too.

To her, falling more and more in love with her role as a housewife, all those things were becoming very foreign indeed. She wore clothes now that her mother ran up for her on the sewing machine. They looked real cute and pretty—and they helped to save money.

But they weren’t glamorous.

She wore her hair in a pigtail during the day—in an old-fashioned upsweep with bangs at night. It was very becoming—Eddie had told her so.

But it made her look more like Tammy than like a woman who would turn heads in a crowd. No, she hadn’t been glamorous. Liz was glamorous. She drew her breath in sharply as the thought stabbed home. Oh, even if she’d tried, could she ever have been the world-famous beauty that Liz was?

She’d liked to stay home nights, curled up on the family chair with a sleepy Todd taking his bottle on her lap, and Eddie sitting across the room, smiling at them.

Now she could remember what she never noticed then—that Eddie would get up from his chair to prowl restlessly around half a dozen times in an evening. That when he sat down again, the smile would be growing forced.

She knew he loved their children as much as she did. Yet why hadn’t it occurred to her that while she took care of them, loving every minute, there was nothing for him to do but watch?

She knew she was being the kind of wife every woman is expected to be, and she knew she was happy at it.

It never struck her that one man in the world, her man, might be the exception to the rule.

“Love,” she said later, “can make you very blind.”

Had she been blind to her own faults—as well as to Eddie’s?

Every paper that had printed Eddie’s statement to the press had run a picture along with it—a picture printed for the sake of irony: a picture of Mike Todd and Liz with Debbie and Eddie. “In happier days” most of the papers had labeled it. At the beginning, Debbie hadn’t let her

eyes so much as rest on it for a second; it simply hurt too much. Now she stared at it for minutes at a time.

And saw in it what she had never seen before.

It had been taken months before Mike’s death at England’s most famous race track. There they were, the four of them, walking along—and looking so very much like themselves.

There was Mike, racing form in hand, with that slight smile on his lips, the smile that meant he was perfectly at home, in his own element, in the world he loved best—a world of loud noises, quick laughter, hearty men and beautiful women.

Beside him walked Liz. Her hair was pulled away from her face in a sleek, smooth chignon. Her white suit-jacket draped over her hips in the latest line; the collar stood away from her neck to frame the perfect face. She walked as a woman walks when she knows she is beautiful and desired, that men stop to look at her.

Next to Liz—Eddie. His pipe was in his mouth, his hands plunged in his pockets. He was looking at Mike and Liz and on his face was a smile of complete joy—and a touch of worship. “Look at me,” his eyes seemed to say, “a poor kid from Philly, and here I am with the most exciting, witty, wonderful people in the whole world. Man, this is living!”

And then—herself. She was wearing a simple black dress and, as a concession to Eddie, she carried a white mink stole. And her smile, as the photographer caught her eye was—shy, almost apologetic. “What am I doing here,” it seemed to say. “Well, it’s fun—but it’ll be more fun to get home to my baby . . .” And because of the smile, even the black dress and the white mink couldn’t make her look like Liz. She seemed more like a little girl in mama’s best outfit—a little girl, along for the ride.

That night, she’d had another argument with Eddie. Liz and Mike were taking off for somewhere or other, on another of those endless voyages. Eddie wanted to go.

“But we have to get home to Carrie,” she had protested. “We haven’t seen her in days.” She kicked her shoes off and lay back on the bed. “Besides, we can’t keep up with Liz and Mike. They’re too fast company for us.”

Reminded of his daughter, Eddie had agreed to go home. But he had been wistful, saying goodbye to the Todds. There goes romance. There goes The World . . .

Had she lost her husband, not to the world’s most beautiful woman, but to a way of life, a dream? Had she, despite her love for him—or maybe just because of it—cheated Eddie somewhere?

Had the fault been just a little hers to share?

Huddled in a corner of the big chair, she could see the picture, memorized forever. Would it have ended differently, more happily, if she’d been less the wife she was—and more the woman Eddie wanted.

Could she have been that glamorous glittering woman that Eddie seemed to want now? Should she have tried to be? I’m pretty, she assured herself. But was she pretty enough to compete with the violet eyes and sculptured beauty of Liz Taylor? She buried her face in the tweed of the chair and fought against tears . . .

It is lonely in the Fisher house, and empty. No matter whose fault it was, no matter who was right and who was wrong, it is a sad, silent home.

And in the big chair, bought to hold a family with their arms around each other, Debbie Reynolds sits alone—and wonders—and waits.

—IRENE REICH

WATCH FOR DEBBIE IN M-G-M’s “THE MATING GAME.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958

Why Elizabeth Taylor Turned To Eddie Fisher?

Parodi

17 Mart 2024Generally I don’t learn article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very compelled me to try and do so! Your writing taste has been amazed me. Thanks, very great article.