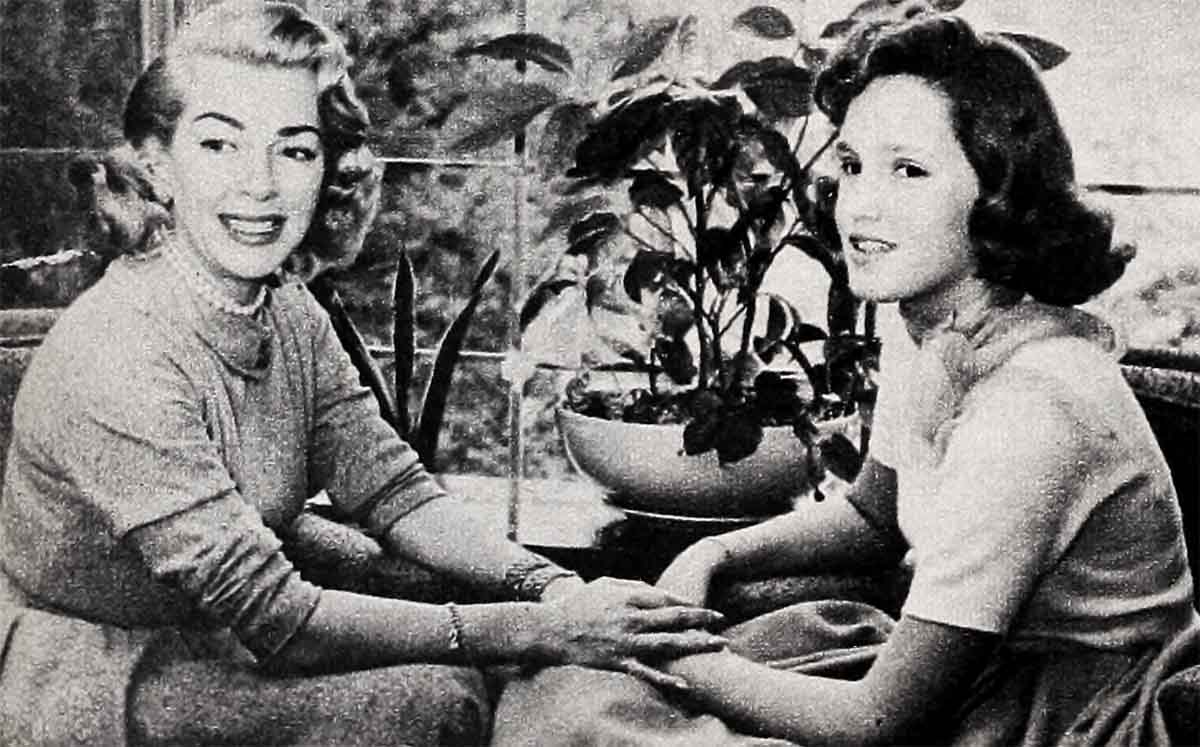

When There’s A Daughter In The Housemates—Lana Turner & Daughter Cheryl

On the set of 20th’s “The Rains of Ranchipur,” dressed in faded-blue denim play clothes, Lana Turner looked like a young girl, a beautiful young girl. It was hard to realize she was the same Lana Turner who portrays the glamorous Lady Esketh in “The Rains.”

Lana’s expression was a happy one and her eyes sparkled with eagerness, for she was talking about something very near and dear to her—her daughter Cheryl—and of her hopes and dreams for Cheryl.

“Cherie is twelve now,” Lana was saying. “She’s right on the threshold of her teens—the ‘perilous teens’ as they’re known to so many parents. I’m young enough to remember them well, and I can recall how important everything seems at that age. You feel you have to live life all at once, before it gets away from you. You don’t want to miss out on a single experience. You’re afraid if you do, you’ll be left behind, and you’re scared to death of that, of being called a wallflower. You desperately want to be liked by everyone. I know; I went through it all. And how I would have appreciated it if someone had just given me a set of rules to guide me through that growing-up period.

“Instead,” Lana continued, “it’s taken me ten years of experience and study to find out some of the important answers to life. Now if I can impart them to Cheryl while she’s still young, she will be spared many of the mistakes I made and that countless other teenagers have made throughout the years because they’ve had no one to understand or advise them.”

As Cheryl steps into the teen age of awareness and starts upon a busy round of parties, dates and the general business of growing up, Lana knows that one of the first items on her daughter’s list of new-found interests will be boys. Lana and her husband, Lex Barker, look forward to the time Cheryl starts dating, just as Cheryl herself does, and sometimes they make a game out of discussing Cheryl’s first date.

Lana will start the kidding by saying, “One day it will happen, Cherie, I just know it will. I can see it all plainly. It will probably be a Sunday, and we’ll be sitting in the living room, reading the papers. Suddenly the doorbell will ring. We’ll look at each other, wondering who it is. Then I’ll answer the door, and there will be a funny-looking fellow, his hair probably combed into a ducktail, with a hot rod parked in the driveway.”

At which point Cheryl laughs, “Oh, Moth-er!”

“Yes, he’ll be standing there,” Lana continues. “He’ll be wearing jeans and a leather jacket, and his hands certainly will be crammed into his back pockets. And he’ll probably be chewing gum, looking like a cow chewing its cud.”

“Oh, Moth-er!” Cheryl laughs again. The picture is too much for her.

“Hi, Mrs. Bark-er,” the young man will say, according to Lana, speaking between lusty chaws on his chewing gum. “Is Cher-yl in?”

“Oh, Moth-er!” Cheryl exclaims once more. “You know it’s not going to happen that way. You know I have better taste than to go out with a rude boy like that.”

Then Lex, whom Cheryl affectionately calls Po, chimes in on the fun. “Perhaps I’ll be the one to answer the door. I’ll say to him, ‘What’s your problem, son?’ ”

“But, Po,” Cheryl argues, “he’s supposed to be coming to see me.”

“Well, sure, I know that,” says Lex, continuing with his version of the story, and pretending to be talking to a young man standing in front of him. “Haven’t you got the wrong address, son?” Then, in a young voice, he says, “Is Cher-yl around?”

By this time, the scene has become so real to Cheryl, she is hanging on every word. “Go on, Po,” she urges, “what’ll you say then?”

“Son,” Lex continues, sounding stern, “when I was your age, we were never allowed to call for girls with our hands in our pockets. And we were told to ask for them as Miss So-and-So. Now, if you think you can handle that, let’s hear it.”

All of this greatly stirs Cheryl’s imagination, says Lana. For, like any other twelve-year-old girl, she enjoys dreaming of the dates that lie ahead. She is amused by Lana’s and Lex’s joking pictures of her first boyfriend-to-be, but she also sees the seriousness beneath it all. She knows that what Lana and Lex are trying to convey to her is that they are interested in and concerned about the kind of boy she will go out with. And, ten to one, when she does start dating, Cheryl will want the boy to be someone she will be proud to introduce to her folks.

Just as a girl of twelve dreams of future dates, so she dreams of being grown-up, says Lana. In fact, she wants to get there in one quick rush. Usually, she thinks the way to do it is with lipstick, high heels and formal clothes. Realizing this, Lana has advised Cheryl, “Leave things to look forward to. Don’t spoil the happiness and excitement that belong to the teens by doing things ahead of time.”

Lana knows what pressure an eager young girl can put on her mother. She is young enough to remember how she tormented her own mother at that age. So she understands Cheryl’s feelings when she begs to be allowed to use lipstick. Her excuse, of course, is the time-worn one of “all the other girls do it.”

However, Lana refuses to be moved by such pleas. “Cheryl, honey,” she says, “you’re not all the other girls.”

“But, gee,” counters Cheryl, “all the other mothers let them.”

“Cheryl, I’m not all the other mothers,” says Lana, then goes on to explain why Cheryl shouldn’t wear lipstick at her age. “You’re only twelve, Cheryl. The lipstick, high heels and formals go with fifteen, sixteen and seventeen. If you do all these things now, everything will be old-hat then, and you’ll just be restless and dissatisfied with life.”

This is all a part of Lana’s belief that it is very important for a young girl to always have a goal toward which she can move during the process of growing up. In this way, she won’t become blasé and start searching for other thrills that may get her into trouble.

One of the most important ideas Lana has tried to instill in Cheryl is found in the Golden Rule—to do unto others as you would have them do unto you. This, Lana believes, is not just a saying in the Bible to be memorized, recited, then forgotten.

“It took me some time,” she says, “to find out that the Golden Rule is the secret of happiness, and that one’s pleasure comes from giving rather than receiving.”

Lana began teaching Cheryl this rule when she was just a tot. For instance, if Cheryl had two cookies, Lana would urge her to offer one to a friend. “It was only a little thing,” says Lana, “but that’s all a small child can grasp.”

Later on, when friends came to share the swimming pool, Lana would urge Cheryl to offer them her best and newest toy instead of keeping it just for herself.

“You don’t need to worry, Cheryl,” Lana would say. “Everything you give will come back to you eventually. Maybe in a different form, but it will come back. And when it does, it will be much more delightful and wonderful than what you gave—even if it’s just the feeling inside of warmth and happiness.”

Lana feels that by now, Cheryl should realize that there are other gifts such as patience, understanding and time which require, perhaps, greater sacrifice and mean more than material gifts. To help Cheryl understand this, Lana often asks her to run little errands—perhaps to bring her a sweater, or a glass of water, or the newspaper—because, “I should like so much to have Cheryl experience the pleasure that acts of thoughtfulness give not only to others, but to oneself.”

Lana has another theory for Cheryl, one that has been of so much use to herself since she discovered it: Change the attitude and you change the problem.

“That’s just good old common sense,” Lana feels. “If you have a problem and you sit around despairing about it you make the problem even bigger. If, on the other hand, you change your attitude, the problem will often unravel itself without any trouble at all.”

Lana has shown Cheryl how to use this idea in her school work. Once, when she was in the third grade, Cheryl brought her arithmetic book home and threw it down in a fit of childish impatience. She could not understand it, she said. It was silly and horrible. Lana suggested that she look at it from another light. Arithmetic, she explained, was really a challenge, a kind of game that could be fun. Cheryl grasped the idea and, on her next report card, she got a “B” in Arithmetic.

Lana feels that since Cheryl is now entering her teens she will find this rule especially useful, for these are the years when what seem like small troubles to adults loom large and menacing to a teenager. “If Cheryl can just learn that most of her problems spring from her own attitude, she will be on her way to solving them.”

Lana’s next bit of advice for Cheryl is: Learn to accept responsibility.

Lana has tried to instill in her daughter this sense of responsibility from the very beginning. Cheryl has always had a certain number of chores to perform around the house. She has been expected to make her own bed and straighten up her own room. She is supposed to feed her dog and bird, to tidy up their quarters, and to keep her white shoes cleaned. Sometimes, of course, she has had to be reminded to do these things.

“I guess,” laughs Lana, “all mothers are familiar with that often repeated refrain, ‘Later, Mommy, later!’ ”

Now that Cheryl is older, Lana feels these few chores are not enough for her. So while Cheryl was away at camp last summer, Lana discharged all her servants.

“We’re now doing our own housework and cooking,” she explains. “Cheryl sets the table and helps with the dishes and does all the ordinary chores around the house that other girls her age are being trained to do. I’d like to have her learn how to prepare meals, too, simple things at first.

“I missed this valuable training because I went to work at fifteen and the little M-G-M school I attended didn’t have a cooking course such as they have in regular high schools. I’ve always been embarrassed by my deficiency as a cook.”

Lana has definite reasons for feeling that this training is necessary for her daughter. Of course, Lana is preparing for Cheryl’s future in a material way. But she realizes that financial security is never a certain thing and that it is far more valuable for Cheryl to know how to get along in the world so that she can take care of herself. When Cheryl reaches adulthood, Lana wants her to be able to say, “Whatever happens I can support myself, feed myself, do the things that other people do.”

That is why Lana also wants Cheryl to attend college, and has been talking about this ever since Cheryl was little. (Lana believes that if you repeat a thing often enough it will eventually take effect.)

Right now, Cheryl is in the typical twelve-year-old stage of only wanting “to have fun.” Her attitude is that familiar one of, “Once I’m out of school, I’m never going to be bothered by it again.”

But Lana realizes this is only a phase not to be taken seriously. She doesn’t argue with Cheryl about why she should go to college. She knows that if she does, she will just be tuned out.

“Cherie,” Lana says instead, “I’m not going to make the decisions for you. But why don’t you give it some thought, because I imagine that going to college is a very wonderful life. I wasn’t lucky enough to get the opportunity myself.”

Lana notices that Cheryl is beginning to be a little curious about this interesting life which her mother speaks about so wistfully. And Lana is sure that as time goes on and Cheryl nears the end of high school, she will be eagerly looking forward to college.

Another bit of advice Lana has for Cheryl is: Keep busy; don’t let boredom get you.

Lana realizes that the three months of summer vacation can be full of dangers for teenagers unless they keep themselves occupied. So she and Cheryl made an agreement. Lana arranged for Cheryl to take lessons in her two favorite sports—ice skating and tennis—and Cheryl in turn agreed to study French.

“The knowledge of at least one foreign language is good for a girl,” Lana feels. “It gives her a sense of accomplishment and this in turn gives her the assurance that she greatly needs in her teens. Not that she doesn’t know what might pass for a foreign language now,” Lana laughs, thinking of the jive talk that floats around the house whenever Cheryl and her friends are there. “There’s no dictionary to help you with this language. Why, an entire conversation can get going right over your head!”

This jargon, Lana knows, is only a preview of the teen-age era that lies ahead. But, like most mothers caught in a similar situation, Lana doesn’t want to show her ignorance by flatly asking Cheryl what she’s talking about. The furthest she dares go is to ask casually from time to time, “What did you tell me is the new word they’re using for such-and-such?”

One other sound piece of advice that Lana gives her daughter is: When in doubt, don’t.

Cheryl is already being influenced by the effects of the gang stage, and Lana knows that as her daughter proceeds through her teens, the instinct of doing everything the others do will become more and more pronounced. She herself can remember that just about the worst agony in the world was to be considered a wet blanket by her friends.

But there are bound to be some girls in the group who will try to persuade the others to join them in questionable pursuits. Consequently, Lana tells Cheryl, “Remember one thing: You are a lady. That doesn’t mean you have to be stuffy or prudish or prim. But, darling, think twice before you do or say something that might either cheapen you or embarrass someone else. Try to be tactful, and if something’s going on that you just don’t feel like being a part of, walk away from it. But you can walk away with a smile.

“If someone says, ‘Aw, come on, you’re being silly,’ you can answer honestly, ‘Well, you kids go ahead. I just don’t happen to like that sort of thing. But don’t let me stop you.’ ”

Because Lana and Cheryl have always been good friends, Cheryl listens to her mother’s advice. More than once she has turned down invitations to parties because she knew her mother would not approve of them. And she has found out, too, that her action has influenced other girls in the group to follow her example.

Another thing that Lana tells her daughter is: Always feel free to invite your friends to our home.

“I know how important this is to a young girl,” Lana says. “You see, when I was Cheryl’s age, we boarded with other families. They just didn’t understand that teenagers can’t help being noisy sometimes. They’re sprouting feathers, spreading wings, trying to learn how to fly. So often I was told, ‘Don’t bring those rowdy kids around here any more.’

“I hope there will always be such an atmosphere of warmth in our home that Cheryl’s friends will want to come over,” Lana says. “And isn’t that better than flying off to the beach with the blankets and the cars?”

Lana assures her daughter that not only will her friends be welcome but that she will want to know who’s coming so that she’ll know their names and can greet them and make them feel at ease. Letting a girl bring in her friends and being allowed to entertain them as she pleases, Lana feels, gives her a feeling of confidence which is so important to a teenager. If the art of meeting people can be acquired in these years, it will help her all through life.

“I still am so shy,” Lana confesses, “that, when I walk into a room or meet new groups of people, I just die inside. I guess most of us suffer from a bit of shyness. Even the big bully who swaggers around and makes a nuisance of himself is just covering up his feeling of insecurity in the hopes that no one will know how he’s quaking.”

Lana has taken great pains to explain this to her daughter, because she knows it will help put Cheryl at ease when she finds herself in the presence of strangers.

“If you just realize, honey, that the person is as shy at meeting you as you are at meeting him,” Lana tells her daughter. “If you’ll only take time to think about that, it opens the way. In no time at all you’ll be talking like old friends.”

Lana also has a valuable warning for Cheryl: “Remember, darling,” she says, “whatever you do, in the end it will be yourself whom you will have to face.”

Of course, for a girl to understand this fully, she will have to know the difference between right and wrong. And, in Lana’s book, the sooner a girl learns this, the better equipped she will be to face her teens. Also, it is so important for a mother to be tolerant of the faults and naughtiness a child is certain to exhibit in the process of growing up.

“I know very well the temptation to give up in despair and say, ‘My child! How could she do that kind of thing!’ But,” adds Lana, “if we can just realize that the child is having as difficult a time as we are, the troublesome periods will only serve to draw us closer to our children.”

Lana recalls, for instance, Cheryl’s “untruthful period” when she was eight.

“When they tell you such bland lies, looking you right in the face like angels,” Lana says, “it helps to know that this phase is normal. Yet, of course, you can’t just take for granted that it will pass. You can’t take a chance on letting your child grow up saddled with this habit. You have to be a detective, quietly checking with other people, until finally you get to the truth.”

Once Lana had the truth she would listen quietly to Cheryl’s story. When the child finished Lana would say, “Now look, honey, let’s stop kidding around. You’ve had your fun. You’ve told a whopper. But I know what really happened. You see, there really aren’t any tricks or fibs or excuses you can think of that I haven’t pulled myself. My mother did it before me. And your child will do it after you. So let’s discuss the problem openly without any beating around the bush.”

Lana discovered that the resulting frankness between her and Cheryl more than made up for the trouble it had taken to ferret out the truth and have the patience to talk it over with Cheryl.

Today Cheryl finds it difficult to tell a lie. Sometimes, if she tries, her conscience troubles her so much that she comes to her mother of her own accord, admits it, apologizes and even cheerfully chooses her penalty. Because Cheryl has this active conscience, Lana is sure that

she will get through her teens with flying colors.

“You see,” she says, “I don’t guarantee Cheryl will wear a halo or fly around with wings, but I do think she’ll find herself on a sensible footing.”

Lana tells her daughter, “Cherie, if you do something wrong it won’t be any use trying to kid yourself with the thought that your mother doesn’t know about it. I may go the rest of my life without ever finding out. But somebody will know.

“The person that you did it to or with will know. And God will know. When I say God will know, I mean that it will be only natural for you to have a feeling of remorse. And it’s painful when you have to say to yourself, ‘I wish I hadn’t done this.’ It’s a pain which you are giving God, and it will come back to you a thousand-fold. If you don’t follow your conscience, Cherie, you are the one who will suffer.”

Lana’s last bit of advice to her daughter is: If you have any questions or any problems, please come to me and we’ll discuss them together.

“I feel confident Cherie will do just this,” Lana explains, “because even when she was little we always talked things over and I answered all her questions. I’ve tried to be as frank and open with her as with my friends.”

Lana feels that ignorance is the biggest cause of the troubles teenagers have today. So many of them have to find out the answers to their questions from outsiders. And often the information gained from these sources is wrong and the boy or girl only becomes more confused.

“The child who has the intelligence to ask a question,” Lana contends, “also has the right to have some kind of an answer. Maybe you can’t give it as the book would. But you can present it to him in a way that he can understand. And that goes for every subject from God to sex.

“I tell Cherie: ‘Darling, you have a lovely body. God has given you that. Be proud of it, but don’t be overly vain. And always remember this: Your life can be one of great happiness or of great pain. It will all depend on the consideration and respect you show yourself.’ ”

Lana maintains that being able to talk so plainly to one’s child today is proof that the world has been growing up in the past fifty years. She points out that people were once ashamed to admit to such diseases as tuberculosis and cancer. They were even afraid to see their doctors when they were ill—to say nothing about their reluctance to tell their children the facts of life.

“The result of all this,” says Lana, “was that people lived in fear and ignorance. And if you steer by those dark stars you’re following a bad course. Knowledge alone lets in the clean air, and problems can’t stay where the wind is blowing.

“I look at it this way. If we can only save our children one ounce of hurt or the feeling of stupidity such as we suffered during our teen-age years, if we can give them an understanding they can carry with them the rest of their lives, then we have succeeded in helping this old world along to a brighter day. Because, if what we pass along is really deep enough, our children will hand it on to their children with, perhaps, a little additional wisdom of their own. And I believe that is the real meaning of evolution.”

From all this, it is obvious that Cheryl Crane has a pretty wonderful mother—and that Lana Turner has a pretty wonderful daughter.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1956