Hollywood’s Biggest Comeback

We had to bring you this story. Because, from the hundreds of letters Photoplay has received, we know that it intrigues you as much as it does us. Because it is the biggest story in Hollywood today, and nothing like it has ever happened before. Because it is the story, not of one star’s comeback, but of many stars’. Because, in drama, pathos, comedy, tragedy, thrills and surprises, it has never been equaled.

Suddenly, they live again on your home screen: the eternally lovely face of Greta Garbo, the gay and lively charm of Carole Lombard, the dark magnetism of John Garfield. “It’s fascinating to see Hollywood’s history unrolled on your home screen,” you’ve written us, and deluged our office with queries about the old-time stars and their movie classics. As TV fans, eyeing your sets in awe, you’ve proven you’re still movie fans at heart. (In one typical week, viewers devoted 36.8 per cent of their TV time to old movies!) And, to a new generation—today’s teens—stars are nightly being born anew.

“Please tell me about Greta Garbo, please,” letters read. “I’ve asked my mother but she can’t remember much.”

“I just love Jean Arthur,” wrote a Texas high-school student. “She’s my ideal. Tell me, is she still acting?”

Photoplay staffers started tracking down the answers, became so intrigued that we ended up with this, the first of a two-part article. We enjoyed every minute we spent collecting the information—the time we called up Alice Faye; the day we talked with Cary Grant (who insists “there’s not a kid on the block who takes me seriously since they’ve seen me whooping it up on TV”); the letter we received from Ronald Colman and the day we tracked Greta Garbo to the Museum of Modern Art, star-struck as we watched her viewing one of her old films along with the rest of the audience. For, as with you, we awaited no one’s reappearance more eagerly than of the great, almost-legendary Greta Garbo. New Yorkers have been used to seeing the tall, distinguished-looking woman walking near her home on East 52nd Street and heads have scarcely turned for a second glance at the incomparable features that once cast a spell over the world. Hers was a strange career.

When Garbo first came to this country in 1925, she was young, naive, unworldly, completely dominated by her director, Mauritz Stiller. However, M-G-M soon took over. They decked her out in a track suit for some idiotic cheesecake shots. They set up an interview during which Garbo, with her thimbleful of English, tried to grapple with intimate questions about her private life. These experiences gave her a lasting distaste for publicity, and she eventually became known as the “I want to be alone” girl. A greater blow came when she was assigned to make her first American picture, “The Torrent”—without Stiller.

She was learning English, but her co-workers didn’t know this. They’d call a take with “Where the hell’s the big flatfoot?” or “Get that squarehead on the set.” Garbo understood, but said nothing. There was some trouble, too, with Ricardo Cortez, male star of the film and then a big name. He resented appearing opposite an unknown and took no pains to hide his feelings. Whenever they became too obvious, Garbo would merely mutter, “That pumpkin—he only hurts himself. There will come a day.”

That day came with the release of “The Torrent,” in which Garbo was a sensation. Stiller then counseled her, “You are now a great star, Greta, and in America great stars do not work for four hundred a week. Tell them that until they give you much more money, you will not return to work.” Obediently, Garbo went on strike. But boss Louis B. Mayer proceeded to give her a stern talking-to, and she reported back to the studio, defying Stiller for the first time.

After two more unsuccessful years in Hollywood, Stiller went back to Sweden and died shortly thereafter. Friends believe that sorrow and remorse at his death made Garbo withdraw into the shell of shyness marking her personality in later years. There were to be other men in her life; her romance with co-star John Gilbert rocked silent-days Hollywood and gossip columns still occasionally link her with various notables of the international set. But she has not been married.

As the talkie era arrived, Garbo began encountering boxoffice woes, caused mostly by mediocre pictures. In 1933, she was fifth in popularity; in 1934, she had fallen to thirty-first. Some studio executives wanted to let her go, but Mayer defended her by pointing to her big draw in foreign markets and her “prestige value.” Such great hits as “Camille” and “Ninotchka” still lay ahead, though her last picture, “Two-Faced Woman,” was pretty much of a disaster. Four times nominated for Academy Awards, she never won; but in 1955 she was voted an honorary Oscar for her “unforgettable screen performances.”

Living in serene, well-heeled retirement, free of the publicity that she so bitterly hated, Garbo has to some extent come out of her shell. She is often seen shopping on Madison Avenue or dining with friends in plush spots like the Colony, and she talks readily and knowingly on a wide variety of subjects. But, for her, one topic remains taboo: Greta Garbo.

Among other M-G-M pictures being released on TV are dramas featuring the exquisite profile and ladylike charm of Norma Shearer, also unknown to the latest moviegoing generation. With producer Irving Thalberg, she lived one of the great romantic chapters in the Hollywood story. Canadian-born Norma was struggling as an extra in New York when she received three offers from Hollywood almost simultaneously: from Universal, Hal Roach and M-G-M. She didn’t know it, but the urging of one man had prompted all three offers. Starting as an office boy at Universal, the brilliant Thalberg had become general manager of the studio before he was twenty-one, moved to Roach, and wound up as Metro’s production head.

He had seen Norma playing a bit part and scribbled her name on his shirt cuff for future reference. Years later she said, “I will never cease to be grateful that the first man who really thought I could act thought I’d make a good wife as well.” Two years after Norma was signed, she became Mrs. Irving Thalberg, adopting the Jewish faith for his sake. Dazzling as her career was, through successes like “Smilin’ Through” and “The Barretts of Wimpole Street,” her husband always took first place in Norma’s life. At one time, while Thalberg was recovering from a bout with tuberculosis, she stopped working so that they could live abroad for a year. Even so, the combination of his weak heart and the eighteen-hour day he put in at the studio finally led to tragedy.

Irving Thalberg died in 1936, aged only thirty-seven. But Norma agreed to return for “Marie Antoinette.” After the completion of “Her Cardboard Lover,” in 1942, she was married to Martin Arrouge and retired permanently. Still, she has remained an active and beloved figure on the Hollywood scene. She discovered and promoted Janet Leigh. Just this year, she was instrumental in getting handsome Bob Evans his debut role—as Irving Thalberg in U-I’s “Man of a Thousand Faces.”

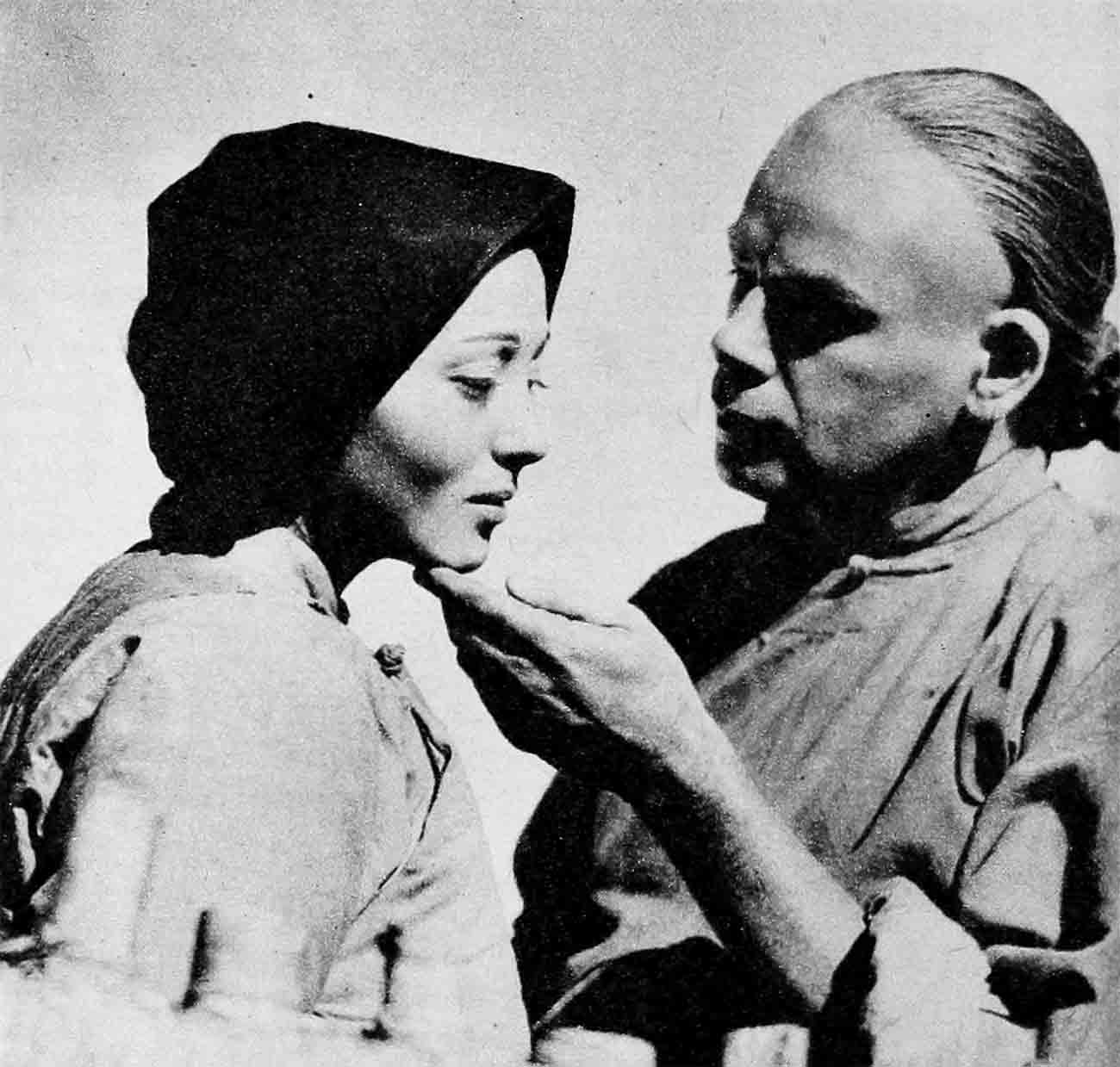

That picture is the life story of Lon Chaney, who scored most of his big hits in the silent era, beyond the range of today’s TV revival. But the talkies have their own champ in the art of makeup, though Paul Muni is known primarily as an actor, revered for his integrity. Warners grew so enthusiastic about his broad talents that they began billing him as “Mr. Paul Muni.”

He was concerned only with his acting and how to improve it. Intensive preparation was his forte, and he became famous for it. He went down into a coal mine to familiarize himself with the locale of “Black Fury,” spent four months exploring San Francisco’s Chinatown before making “The Good Earth,” acquired a grounding in bacteriology for “The Story of Louis Pasteur” (his Oscar-winner), read 300 separate pieces of literature to play the lead in “Juarez”—and spent six months before “The Life of Emile Zola” reading everything he could find about Zola and the Dreyfus case.

Here, obviously, is a perfectionist. The most likely reason for Paul Muni’s disappearance from your theater screen is an unusual one: He just couldn’t find enough top material to meet his exacting standards. Recently, he scored an impressive stage comeback in “Inherit the Wind,” the long-run Broadway triumph. Whatever Muni himself thinks of his current movie comeback—via TV—his memorable performances are going to provide rough competition across the television channels for the actors in more hurriedly prepared live shows, with rehearsal time reckoned in terms of weeks.

Veronica “Peekaboo” Lake, petite blonde from Brooklyn, wowed them in “I Wanted Wings,” as a femme fatale whose long hair kept falling over her right eye. Veronica became a star—and started a fad. The wartime Manpower Commission even issued official warnings to any women factory workers who copied it, fearing peekaboo bobs fouling up machinery.

For a while, Veronica was a top feminine star at Paramount, teaming five times with Alan Ladd. But in 1950 she left Hollywood, complaining that her working hours allowed her too little time for her children. It’s interesting to speculate how she might feel on seeing herself again as a national symbol of sex appeal, for she now does only an occasional part in a play, in summer stock or on the road. Married to Joseph A. McCarthy, New York writer and music publisher, Veronica had one child by her first marriage, to John Detlie; three by her second, to André de Toth. In each case, the father now has custody.

If your ideal of feminine allure is Marilyn Monroe, perhaps you’ve been skeptical when veteran fans say, “Call this new crop ‘glamour girls’? You should have seen them in the good old days. Ah, Jean Harlow . . .” Is this merely nostalgia? You have a chance to check up, as Jean’s spectacular figure and naturally platinum blonde hair appear on your home screen.

Born Harlean Carpenter in Kansas City, Jean became at five the victim of a broken home, and her own marital fortunes proved even more unhappy and more dramatic than those of such later sex symbols as Marilyn, Lana and Rita. At sixteen, Jean rushed into marriage with rich playboy Charles C. McGrew III. (“The radio next door was blaring the ‘St. Louis Blues’ as we listened to the words that made us man and wife.”) They settled in Hollywood, where McGrew dared her to go into extra work. Jean took the dare, but the two were divorced by the time she flashed up from extra ranks into the man-killer role in “Hell’s Angels.”

Fans were agreeably shocked at flamboyant film personality and her revealing clothes. Friends and associates knew Jean herself as a straightforward, endearingly natural person—usually laughing and vivacious—with a one-drink limit at the cocktail hour and a minimum of confidence in her own ability as an actress.

To be frank, Jean didn’t show up as an her accomplished actress in her early pictures. (Keep that in mind if “Public Enemy,” for instance, turns up on TV.) But she became a first-rate, sparkling comedienne in such hits as “Red Dust,” Woman” and “Dinner at Eight.”

On the personal side, her bad luck continued, probably helped along by those “Redheaded who confused her gaudy screen self with the actual woman. “I’m so tired—so very, very tired of men trying to paw me,” she told a friend. “Sometimes I think it would be nice if I never saw another man.” But she changed her mind when she met M-G-M executive Paul Bern, understanding friend of many stars—and apparently the first man Jean knew who wasn’t mentally undressing her with every look. They were married in 1932. One terrible night two months later, Bern shot himself, leaving a suicide note that began, “Dearest dear: Unfortunately this is the only way to make good the frightful wrong I have done you.”

Loyally, Jean never said a word about the meaning of that cryptic note, though she realized that all the leering speculations about it might ruin her career. was not officially closed for two years, and during that trying time she was comforted by cinematographer Hal Rosson, with whom she eventually eloped. That marriage lasted eight months.

Then she met William Powell. “I had thought I was in love before, but I never knew the meaning of the word until I met Bill. I never thought it would really happen to me. I’m afraid of it. I have a feeling we will never be married . . .”

For Jean Harlow, time was running out. With only a week’s shooting to go on 1937’s “Saratoga,” she died of cerebral edema—at twenty-six. Now “The Jean Harlow Story” is in preparation in Hollywood, and a present-day siren faces a challenge. She must follow in the footsteps of the lady Clark Gable once saluted as “the swellest girl on earth.”

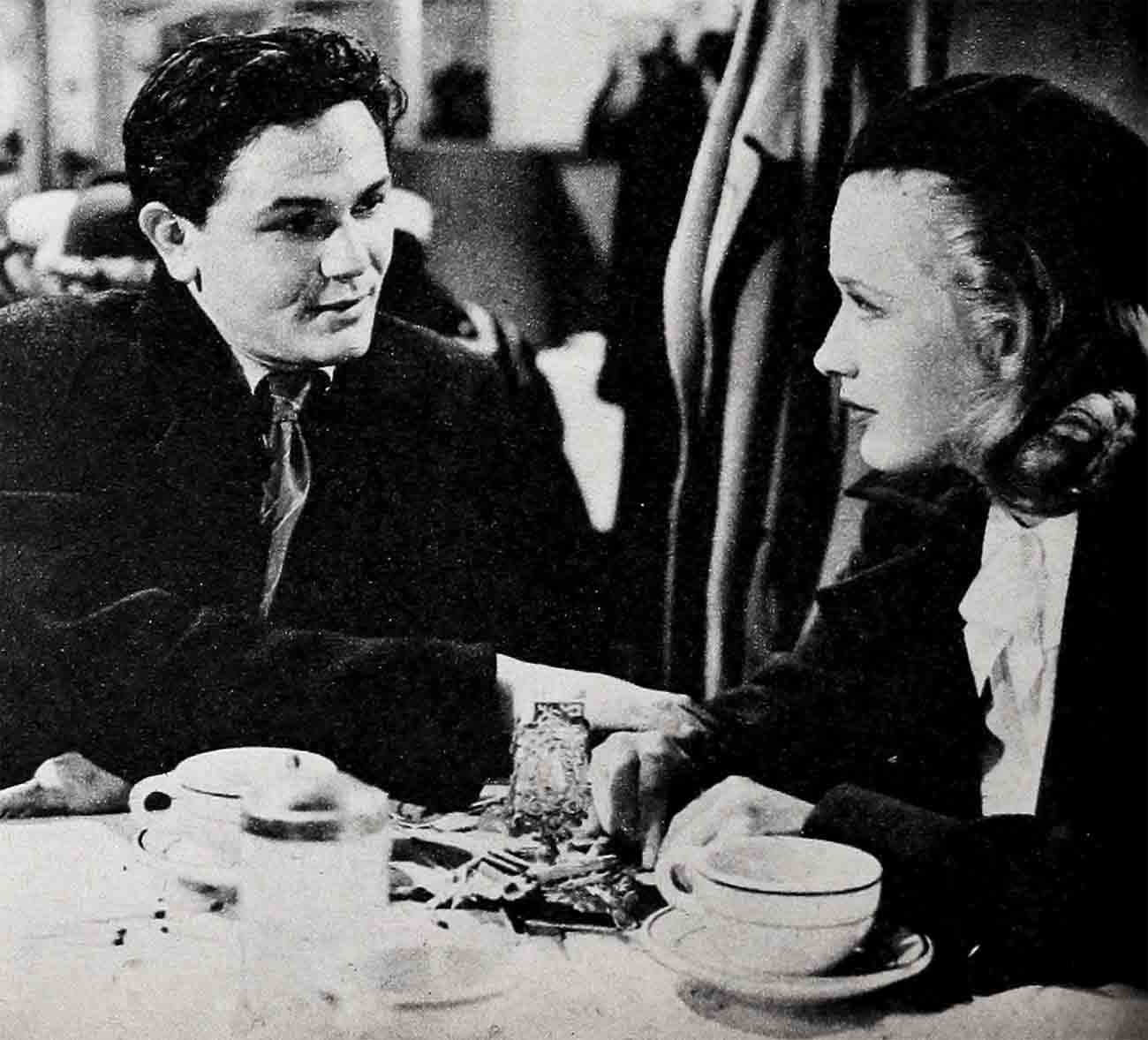

Opposite Priscilla Lane in “Four Daughters” (and later hits) was a newcomer whose life pursued a much stormier course, John Garfield. His irregular features, his rough virility, his air of honesty won him immediate attention and an ardent feminine following. For much of his career, his striking debut role typed him in similar characters: moody, rebellious, self-pitying. The closest modern parallel would be a James Dean or early Brando part.

Garfield’s boyhood made a useful background for these assignments. Growing up on New York’s Lower East Side, Jules Garfinkle was on the way to becoming a young thug; his despairing father even placed him in a school for problem children. But there Julie discovered something more exciting and rewarding than juvenile delinquency: acting. On the stage, Garfield finally drew great acclaim in Group Theater successes “Awake and Sing,” “Golden Boy.” The Group pushed plays of vigorous social comment, compelling for a man like Garfield, whose slum origin made him sympathetic to the underdog. Learning of his attitude, the Communist Party for years used his name in connection with various front organizations without consulting him. Tragic consequences were ahead.

Garfield was riding high in Hollywood. He’d signed with Warners because they allowed him time off for stage work and, said John, “because I get a kick out of working on the same lot with Paul Muni.” In seven years, he made thirty-one films for Warners, mostly of the gangster-prison variety and was suspended seven times. “Parole me!” John once begged.

But his popularity continued, and his life seemed secure, with wife Roberta, daughter Katherine, son David. In 1939, there had been rumblings of political trouble to come, though few show people took them seriously.

In 1945, shadows fell over the Garfield home when their little daughter suddenly died. And in 1951 no one in Hollywood could laugh; John Garfield took the stand to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, accused of Red affiliations. He came as a voluntary witness, to clear his name of the accusations clinging to it for years. On the one hand, he wanted to make a clean breast of the fact that he had, unknowingly, been used by the Reds. On the other hand, he had just produced as well as starred in a new film; his money was tied up in it, and he knew that any Red taint would kill its chances. So he hedged about names, dates and associations, and the Committee labeled his performance unsatisfactory.

Thus died the career of John Garfield. In the last eighteen months of his life, he made no movies. In the last few weeks, he got together with the FBI and determined to set things straight once and for all. It was too late. In strenuous preparation for boxing scenes in “Body and Soul,” he had torn a heart muscle. The effects were lasting; Garfield died of a heart attack in 1952, aged thirty-nine. A friend commented sadly, “He was guilty of two things: of loving people and of being naive. For naiveté, he paid with his reputation.” And, in a way, with his life.

Whatever John’s mistakes may have been, they died with him. But his talent did not. TV-revived, his strong and sensitive portrayals have no connection with politics. They reflect simple humanity.

A rebel of an entirely different sort was Jean Arthur. Indirectly, she ruined a whole day for quixotic Katharine Hepburn. Katie, it’s said, ran up to a publicity man and chortled, “I’ll bet you never had anyone as difficult to handle as me!”

The shattered publicist snapped, “Oh yes I have! I’ve just come from working with Jean Arthur.” He wasn’t kidding; sweet-faced, husky-voiced Jean was the press agents’ despair. After battering at the doors of Hollywood, in three good tries from 1923 on, she had no innocent illusions left. But she had a firm confidence in her own ability, and critics agreed with her when she took to the New York stage. Though her five Broadway plays were all flops, Jean personally drew excellent notices, and this time Hollywood came after her.

Now you may see the happy results in charming, thoughtful light comedies like “The Talk of the Town.” “My personal favorite,” says Jean in the droll little voice that remains her trademark, “is ‘Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.’ ” While her professional stature grew, so did her reputation as Hollywood’s recluse, an American Garbo, a star who escaped autograph seekers and flied to her dressing room between takes.

Jean once explained her behavior this way: “The only times I’m self-conscious are when I’m Jean Arthur. In front of a camera, I lose my own identity completely, and with it, I lose my timidity. As Jean Arthur, I’m never sure just what people expect of me.” Nobody would have expected what she did in 1944: throw over her career to go to college, study philosophy, live among girls half her age, and generally have a ball. She was even less concerned about her once-shining movie career after she became the wife of producer Frank Ross. That marriage broke up, and Ross married Joan Caulfield, but Jean has not remarried. On film, you saw Jean most recently in “Shane,” as Van Heflin’s pioneer wife. It was a dramatic portrayal, glowing, delicately shaded—but so had been all her movie comedy performances. She is another of Hollywood’s generous gifts to TV.

In filmtown’s eyes, Margaret Sullavan was an equally unpredictable character. Long before such conduct became fashionable, Maggie stormed around town in slacks, drove a battered old car, wore no jewelry or makeup. But before the cameras (as you can see now) she delivered the goods, making every scene count with her enormous sensitivity and warm, laryngitic voice. She was a rebel not without a cause; she traces her ancestry back to Dixie’s Robert E. Lee and to fighters of the American Revolution.

For her independence, she has been respected. Two seasons ago, the play “Janus” paid off its fat investment in a fast eight weeks, largely on the strength of the Sullavan name. Formerly married to actor Henry Fonda, director William Wyler and agent-producer Leland Hayward, she is currently the wife of businessman Kenneth Wagg. Upon this marriage, she left films permanently (she says), and regards their new house in Connecticut as home. But in movies like “Three Comrades” Margaret Sullavan remains a personality to be reckoned with, in any medium.

So does Carole Lombard. Carole was the originator of screwball comedy and one of the most colorful characters Hollywood ever saw. She hated stuffed shirts; she loved to trip them up with crazy gags. Born plain Jane Peters, she was brought by her mother to the old Fox lot when she was a child. A casting director commanded, “Cry!” And Niagara cut loose. Grown into her teens, the future Carole began to get bit parts, and her career looked promising. Then an auto accident sent her smashing into the windshield, cutting up the left side of her face. Was she through?

“Get her over to Sennett’s,” advised a friend of her mother’s. “They don’t care about faces. They’re only interested in figures. And she’ll forget herself in the middle of that crazy bunch.”

And the future Carole Lombard served her apprenticeship in the last of the Sennett series, playing the bathing beauty, taking thrown pies in the face, sharpening her wits to keep up with her veteran co-workers in the comic routines. From this experience, she developed her superb comedy timing—and her personal zany streak—and into a beauty.

Even after she became a great success in delicately handled light farces, Carole could kid about an occasional failure: “I sure stunk up that one!” She found an equally honest, forthright person, and his name was Clark Gable. After their marriage in 1939, Carole centered her life on their San Fernando Valley ranch—not on Hollywood. But she was acutely conscious of the horrors going on in Europe. To a reporter, Carole confided, “The world is in a mess. I don’t exactly know what it’s all about, but I can see and feel that we are not worthy of ourselves. There is an American destiny. We’ve got to rededicate ourselves to the spirit of our own Revolution. We’ve got to take it out and sell it.”

After Pearl Harbor, Carole did just that. In her home state of Indiana, she personally sold over $2,000,000 worth of War Bonds. Happy at the results, Carole was eager to go home to Hollywood and her husband. She conferred with her mother and with Otto Winkler, M-G-M publicist and Gable’s best man at the wedding. “I’m strictly a train man myself,” Otto said.

“I can’t face all that time on a choo-choo,” Carole said. They flipped a coin, and Otto lost.

They both lost. The plane crashed. Among the flood of messages that tried to comfort Clark Gable in his dark hour were these words from the White House: “Mrs. Roosevelt and I are deeply distressed. Carole was our friend, our guest in happier days. She brought great joy to all who knew her and to the millions who knew her only as a great artist. She gave unselfishly of her time and talent to serve her government in peace and war. She loved her country. She is and always will be a star, one we shall never forget or cease to be grateful to.”

She is a star, and you may see her now—slender, laughing, forever alive. At first, old movies were just a time-filler. Today, they are an important part of television. TV has found that its shiniest new shows can’t compete on the rating charts with the block-busters of movie history.

Next month, the second part of “Hollywood’s Biggest Comeback.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1957