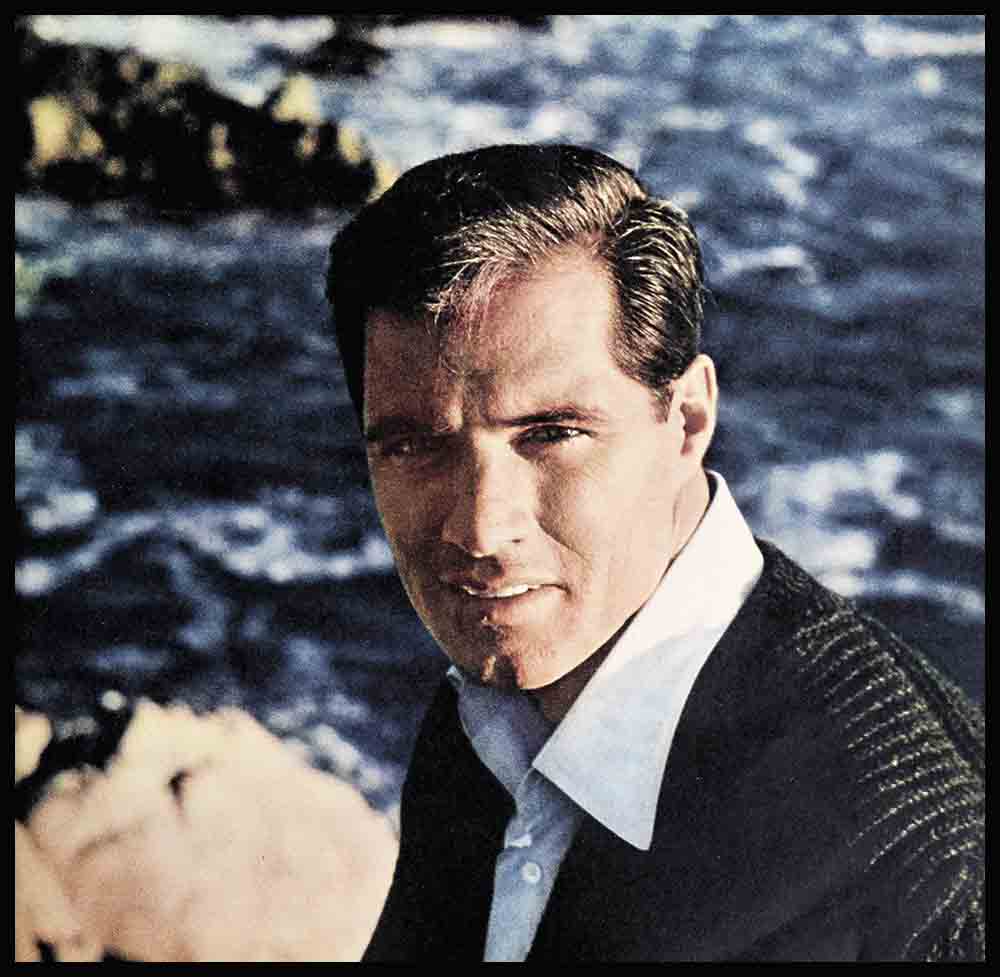

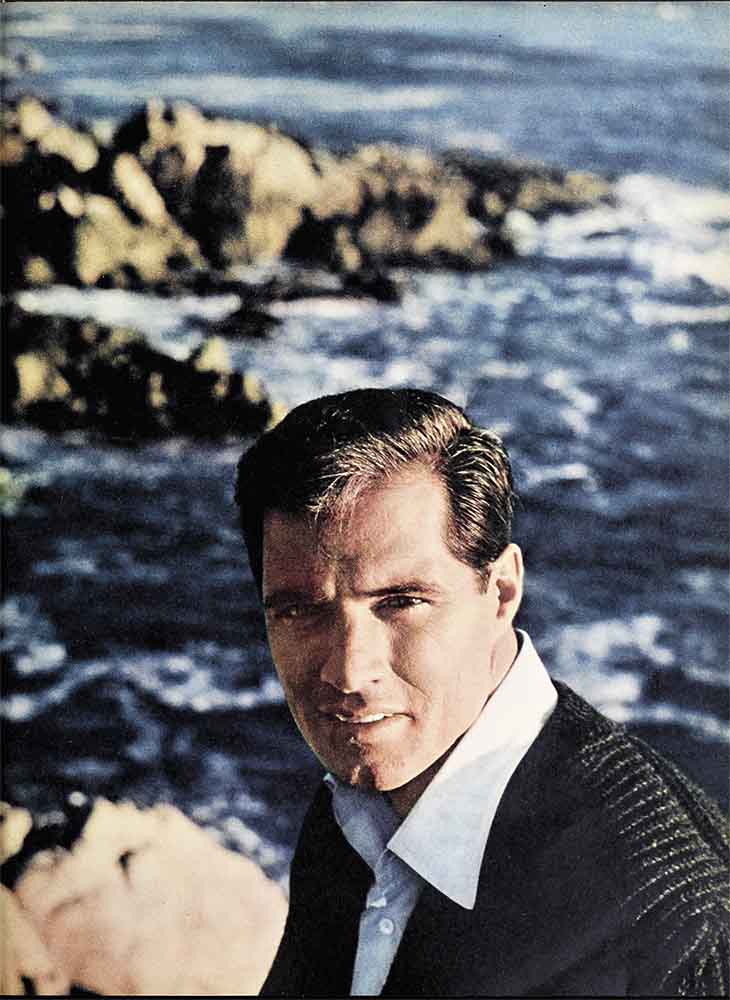

Rebel With A Cause

Way back in the spring of 1955 a tall, dark-eyed lieutenant (Junior Grade, Naval Air Intelligence) received the Order of Balboa from the Government of Panama for his dedicated service as liaison officer charged with establishing relations between the Panamanian Government and the United States Navy. He also received the Order of the Elroy Alsaro Foundation for his contribution to Pan-Americanism. . . . Few officers of his youth or rank had ever been entrusted with missions of such importance as those assigned to him as aide to Vice Admiral (then Rear Admiral) Milton E. Miles. Both the Admiral and other Navy top brass expected John Gavin to make the Navy his career. So did John Gavin. . . . For four years at Stanford, under the Holloway Plan, which finances outstanding Naval ROTC men with an eye to finding officer material . . . for two years as an Air Intelligence officer aboard the carrier USS Princeton (he participated in five battles) . . . and during the year working with Admiral Miles in Latin America, the earnest young officer was dedicated. . . . “Once in a lifetime,” John wrote to his best girl, Cicely Evans, “you get thrown in with a man who is a leader of truly great abilities. Miles is one of the great. He’s given me a whole new concept of what a man can be. He goes to the heart of every matter. No skirting. He moves only in one direction, the one that goes with his standards, his thinking. . . . He’s quite a guy.” The kind of a guy young Lieut. Gavin determined to be.

A few months later he retired from active duty in the United States Navy, but remained active in the Naval Reserve and is now a full lieutenant.

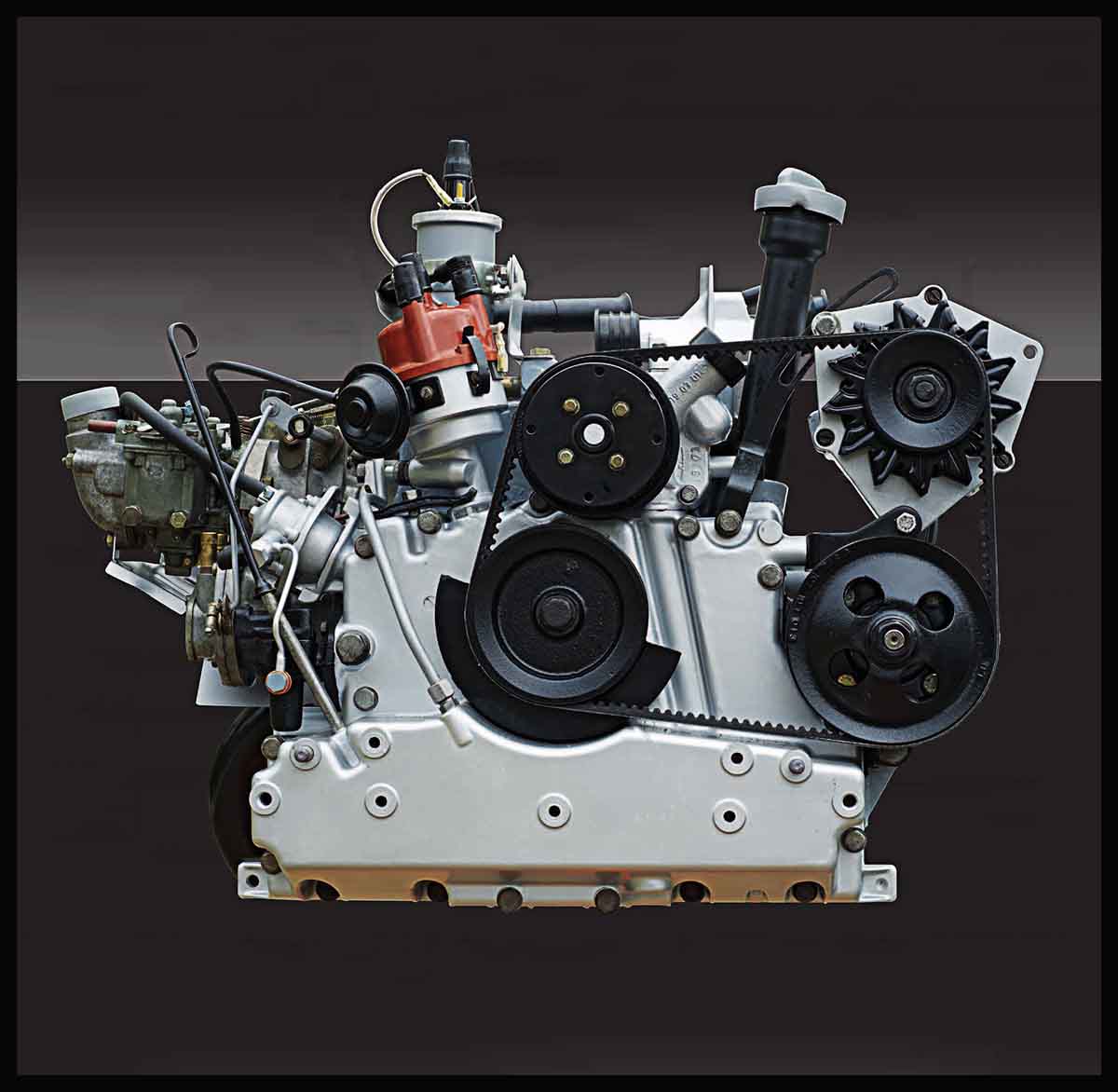

AUDIO BOOK

But by retiring, he was deliberately, drastically, changing the course of his life. His great respect for men like Miles had proved to him that he must move in the direction of his own thinking, and he was restless and impatient. No matter how you excel in the Navy, promotion is slow—and John Gavin couldn’t wait. He’d dreamed once of legal work which might lead to a post in the diplomatic corps, now he determined to go hack to the university and take his graduate law work.

Instead, one month later, he signed a contract at U-I and was on his way to movie stardom. At least in the eyes of his studio it was sure stardom. Jack Gavin wasn’t so sure. In his first press interviews he made an amazing statement. He’d been asked his plans for the coming year and he said, “I don’t know if I’ll be in this business a year from now.”

“They didn’t understand that,” he says now, his eyes smoldering. “They thought I was just playing around dilettante style, that I didn’t care, that I must be loaded with dough and could afford to take Hollywood or leave it. What I meant was that I didn’t know if I’d make good. Even if I learned to act and the studio believed in me—you can’t fool the camera. I’m a pretty reserved guy. The public might mistake that for coolness.”

And he grins, because there’s nothing in the least cool about Jack Gavin. True, he has the formal facade, the straight-shouldered bearing of the military man disciplined not to show emotion. He’s the son of a reserved gentleman from Indiana, a CPA, who trained his son to accept responsibilities. But he’s also the son of a Mexican-born mother. His streak of Latin impetuosity and passion has surprised even those who know him best.

Cicely, for example. They met at a party at his aunt’s home the night before John was leaving for Stanford. Cicely was going to Stanford, too. She is a blue-eyed blonde, “very beautiful in my eyes” and he dated her for four years on campus. Not steady, he had that naval career ahead of him. But by the time they were seniors “we had a pretty good inkling how we felt and where we were going.” But first of all, he was going to sea. Cicely taught school. They corresponded. once when he was home on leave, they were having lunch in a Beverly Hills restaurant when an actors’ agent came over, introduced himself and suggested he get John a screen test. That was very funny. John and Cicely laughed their way through lunch.

It was a year later that it actually happened. Gavin, now out of the Navy, dropped by to see a friend of the family, producer Bryan Foy. Brynie was making a picture about the Princeton and Jack suggested he might help out as technical advisor, since he’d served on that carrier. Brynie grinned. He had a couple of admirals “on board,” he didn’t need any advice, but how would Jack like to play a small part as one of the ship’s crew?

No. He was no actor.

A few days later he picked up the phone and heard his own voice saying, “Hey, Brynie, okay, I’ll do it!” This time Brynie was the one who said no. The part was too small, he’d thought it over and there was no reason why Jack wouldn’t make a good actor. He’d like to introduce him to agent Henry Willson. Henry would cart him around to the studios.

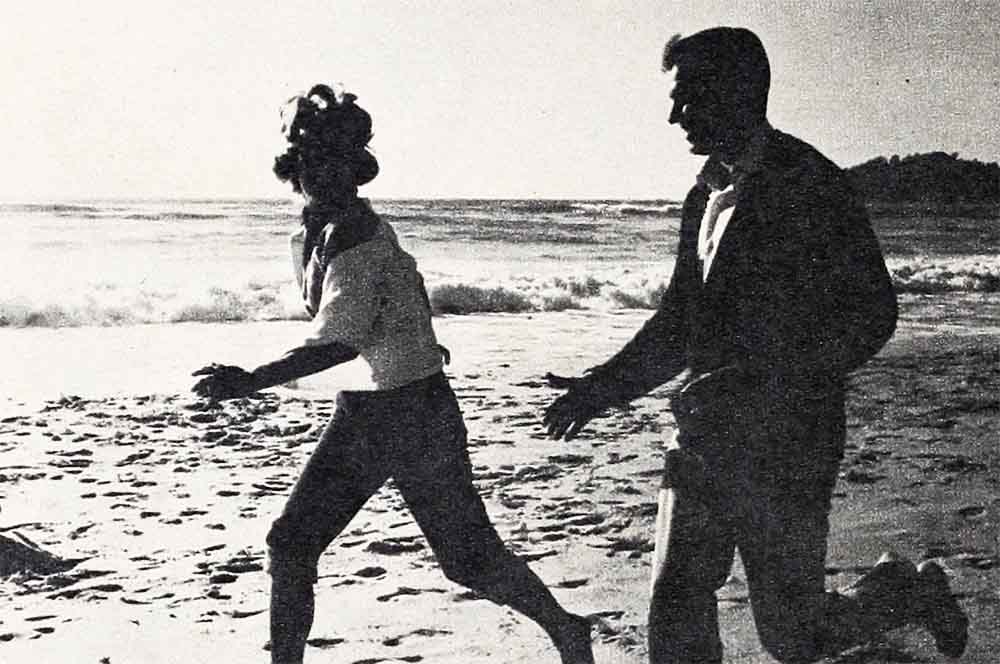

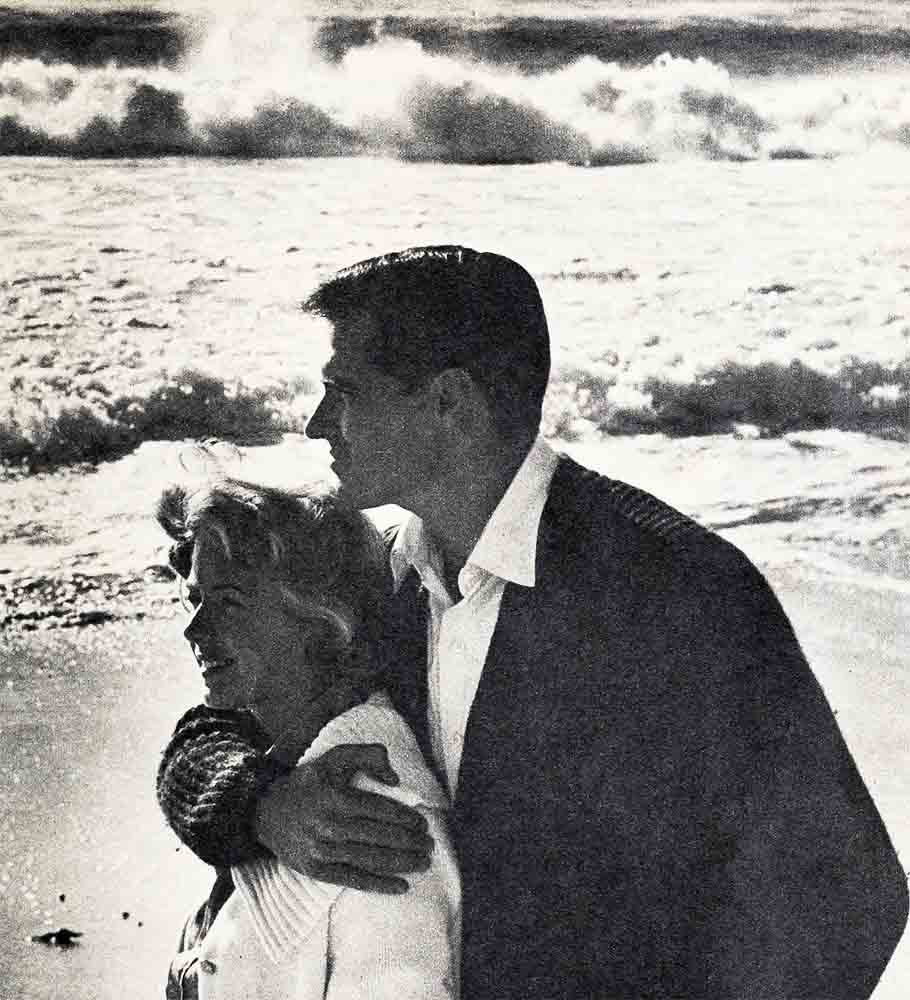

A year later, up to his ears in the new business. . . . “I looked around, decided I’d better do something about Cicely or some other guy might step in and sell her on his brand. She was summering in Europe with a girl friend. I decided to shortstop her in Rome. I flew over, dropped by her hotel, found she’d gone to the post office for mail and took a chance that she might be reading her letters on the Spanish Steps. It was as pat as any script. There she was, standing on the Steps with sunlight all over her, both hands full of letters. . . . I walked up and said, ‘Can you direct me to St. Peter’s?’ It was as if I had eighty violins behind me—you should have seen her face. She dropped her mail, looked up—and it was all right. . . . I wouldn’t have had to make the trip!”

Jack was scheduled for his first starring picture, “A Time To Love and a Time To Die.” He and Cicely came back to America, were married at the Santa Barbara Mission by Franciscan Father Kelly. It was probably the least Hollywood wedding ever. Pete Dailey, Jack’s pal since prep school, was best man. The only guests were family and life-long friends. The couple spent a day of their honeymoon with Admiral and Mrs. Miles in Washington. Then they returned to Europe to spend their honeymoon in Berlin (where the picture was on location) at the famed Kampinsky Hotel.

There’s a strong streak of sentiment in Gavin. There’s also a strong sense of humor. The night little Christine Gavin was born (August 2, 1961), Jack and his pal Pete Dailey left the hospital and dropped in at Dublin’s for a cup of coffee. Handsome Jack was on cloud seven. He’s always liked marriage fine (“it’s the only way to travel”), and now, added to all the rest of it, this unexpected thrill of parenthood. “Something you can’t possibly anticipate, can’t possibly explain,” he tried to explain. “People who don’t have children just don’t know what they’re missing—something marvelous and God-given.” Old Pete—with four youngsters of his own and a fifth on the way—knew how John felt.

“You need a nightcap, Pop,” Pete said, and they dropped in at Dublin’s.

They found the usually sedate restaurant jumping. The pianist was getting a solid beat and first one customer, then another, was airing his lungs in solo. One dignified man imitated Maurice Chevalier. Jack sat nursing his coffee and watching the fun. This was something he could never do. Sure he can speak his lines for a scene—but get up like this in front of people and sing?

Just then his off-beat sense of humor began to work. He excused himself, left the table and approached a huge man at the next table.

“I’m strictly convivial myself,’” he told the stranger. “but this buddy of mine—indicating Pete—“wants a little action. He’s spoiling for a fight . . . with you of course.”

“Oh he is, is he!” growled the fellow and promptly grabbed Pete by the coat.

It took a while to get out of that one. Luckily, Pete is used to Jack’s sense of humor. Luckily, too, he’s a well-built fellow. an ex-UCLA football star. He can take care of himself. And luckily, again, he and Jack react almost identically in any situation.

A fighter, Jack Gavin. Not with his fists as a rule, but with his wits. He doesn’t compromise. All the men he’s admired, the men he’s patterned after, were strong men. Quietly strong. His grandfather, for example.

“I didn’t just love him, I revered my grandfather, he was quite a man.” Jack says. “I used to visit him at his ranch near Sonora, I’d make the rounds with him while he inspected the fields. He was Spanish-born, strong but not bravura—a quiet man with a will of steel. I have a picture of him when he was twenty-eight and he could be me. He had a moustache and his eyes were sea-green; except for that, we were identical. I spoke Spanish with him. That was one thing my mother insisted on, that I grow up in a bilingual house. My dad never really mastered Spanish, to this day the best he can do is ‘Donde es mi cafe?’ which means literally ‘Where exists my coffee?’ . . . In high school, when you want to he just like everyone else, I got embarrassed when my mother spoke Spanish to me in front of my friends. Pretty silly. Spanish was responsible for my becoming Admiral Miles’ aide. What was needed was someone who spoke Spanish and Portuguese.”

Gavin had a good education, his mother and father were particular about that. St. John’s Military . . . “the best school, pound for pound, I’ve ever known. Of course we didn’t think so then, we thought we’d have been better off in Buchenwald than in this prison. I’d go home and gripe, my dad would listen, but the routine went right on, excellent classes with the sisters, military drills with the headmaster and his staff. We had a great football field, a baseball diamond and a distinct sense that certain things were expected of us. Like learning.

“Some of it must have rubbed off, because after St. John’s—well Beverly Hills High didn’t seem to have a very scholastic atmosphere. After a year of it I asked to go to Villanova Prep. There wasn’t anything wrong with Beverly Hills High, it was just that we’d waste a lot of time meeting girls after school and we didn’t get enough homework done. I was used to a stricter atmosphere. Not that we didn’t have fun at Villanova. we did. Saturdays we’d goof off to Ojai, drink pop, munch peanuts and watch the world’s worst movies at the little theater owned by some bandit who knew he’d have an overflow audience, it didn’t matter what he put on the screen.

At Villanova there was a priest who taught trig and solid geometry—a burly man with a keen sense of humor. One day I tried to bluff a trig problem. I’ll never forget that teacher.

“ ‘Sit down, mister,’ he said. ‘You haven’t paid the price.’

“That was the first time I’d ever heard that phrase. There’s a price to be paid for everything and he taught me that if you’re not willing to pay the price, don’t kid yourself.”

It was an important lesson. It was reemphasized for Jack by a history professor at Stanford. He gave tests for which cramming got you nowhere—comprehensive exams which proved deftly and quickly whether you’d paid the price. Jack ran into some great and strong teachers at Stanford. not pedants who told the students what to think. but guides who showed them how to think, how to research. It didn’t happen all at once, but in sophomore year his courses began to have real meaning for him. By senior year he made straight A’s except for one B—in naval engineering.

“Everyone should study acting”

Today he’s paying another kind of price, and the comprehensive exam has to do with your ability to project on that big wide screen. Learning to act is more than a technique, it’s a matter of giving—of self—of understanding people and studying character subjectively. Jack says everyone should study acting, it gives you insight into human beings and their problems. He isn’t content to be just a star, he wants to be a top star, to “bust out” into comedy, into rough-and-ready parts, he wants to be an image with some validity.

His greatest thrill to date was when, as young Caesar, he played an important scene in “Spartacus” (a scene later cut from the picture). When the scene was finished and the director yelled “Cut,” you could have heard a pin drop on the great set. Extras, cast, crew, no one seemed to breathe for a full minute. Charles Laughton walked over and said, in his clipped enunciation, “Julius, you are learning.” It was one of the great compliments of Jack’s life. He loves to excel, he dislikes not to excel.

A lot of people around Hollywood sense in John Gavin some stubborn core of resistance . . . determination . . . and they’re right. He’s always focusing on some objective, having grown up in an environment where you lived by clearly delineated concepts. “In the service you always know where you stand,” he further explains, “but out here in this wild woolly world you have to feel your way. A lot of times when I’m unsure, I kid.”

It’s a sort of kidding on the square, and a lot of people don’t get it. He once told a lovely actress, “Sweetie, you’re quite a beauty despite that eight inches of makeup mask.” She didn’t laugh.

Hollywood, as a matter of fact, never knew who John Gavin was until his war record and his Pan-American activities were revealed. He’d kept absolutely quiet about all that. He didn’t want to make it into the movies via the Navy. But he is a Reserve Officer, and because of his experience in Latin America and his linguistic ability, he has been called repeatedly to attend conferences as a United States envoy. He’s also been called upon increasingly to speak to American audiences explaining our current role in Latin America.

All of a sudden, Hollywood has done a double take. This Gavin is something more than just a handsome young man who stays a little aloof and lives his life his way. It isn’t even that he stays aloof. He has met a lot of people in this town whom he likes a great deal . . . Fred MacMurray . . . Vera Miles . . . Jim Garner . . . many others. Unfortunately, you work with people, become friends, then don’t work with them again for years. And Jack and Cicely have families and childhood friends to keep in touch with socially.

Local boy keeps his head

Jack Linkletter was interviewing him recently. “Say, John,” he said, “you seem like a very regular guy. Have you had trouble avoiding the big head, for example?”

“No trouble,” said Gavin. “You and I have a great equalizer. We’re local boys. We’ve grown up here. Can you imagine someone who’s grown up in this town putting on airs and walking into their friends’ houses? How long do you think they’d last? Movie actor or no, you want to keep your friendships going and you can only do that by being yourself. One touch of phony and they’ll just shrug you off with a ‘get him!’ ”

Jack Gavin doesn’t rush in and make new friends. That’s why he treasures those he’s had for a lifetime. He likes to go home, putter around the house they bought three years ago and rebuilt themselves, making “every mistake in the book.” He figures that every mistake on this house is education for houses to come. . . . He likes to play with his seven-month-old baby. “This is a tremendous enjoyment. I toss her around and she’s a real cutie.” Sundays they take her visiting to her grandparents and Jack carts her little car bed with her in it. He loves this sense of continuing family. He loved the christening when she wore a little dress that had been in Cicely’s family for many years, and a bonnet that had been handed down in his family from generation to generation. . . . He likes a good hearty dinner, then some quiet time to yak with Cicely. He gives her what he feels very sure she needs, a husband who is able to make decisions.

“Women need to be dominated,” he says candidly. “And I don’t mean they’re to be kept barefoot in the kitchen. I mean that no man is happy taking the part of Mr. Milquetoast and no woman is happy when he does. She may challenge a man, but she wants him to answer that challenge. . . . I have a young friend, Robin Cannon, whose dad is a hotel man and a good friend of ours. When he was a little kid I’d take Robin out for a Saturday afternoon of water skiing, diving. . . . It was an absolute ritual—we’d never gone more than a few blocks when he started giving me all sorts of jazz and I’d have to turn around and start driving back to the house before he’d snap out of it. After that we’d have a great time. Now he’s sixteen, and we’re still good friends. Well, a woman is the same way. She’ll challenge, but she’s happy and relaxed when a man meets her challenge and faces it down.”

He likes to play handball with Pete Dailey and to entertain friends and be entertained at their houses. Nothing like the kid at St. John’s who was definitely “not the most gregarious little fellow in the world.” Back then, he once got himself to the point of inviting a bunch of kids to a party—but just before it, he failed to obey his father on a small point . . . something about not coming home by the clock, an offense aggravated by the fact that his mother was in the hospital. So he had to call off the party. If he couldn’t live up to his responsibilities, said his dad. . . .

Well, he’s learned to live up to them, and no studio commitments, no advice from agents or publicity men, no pressures of the press are going to change him. Hollywood was right, there’s a stubborn core of determination and resistance. Jack Gavin is not about to be swept along by life. He wants to find his potentials and use them—all of them. He wants creativity, he’s found creativity; but none of that’s enough. He wants to grow, he wants to excel, he wants to take only the one direction that goes with his standards.

He’s a rebel, yes, but with a cause. A man willing to pay the price for his own integrity.

—JANE ARDMORE

John Gavin is in “Back Street” and in “Spartacus,” both U-I.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1962

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments