When Love Scenes Get Hot

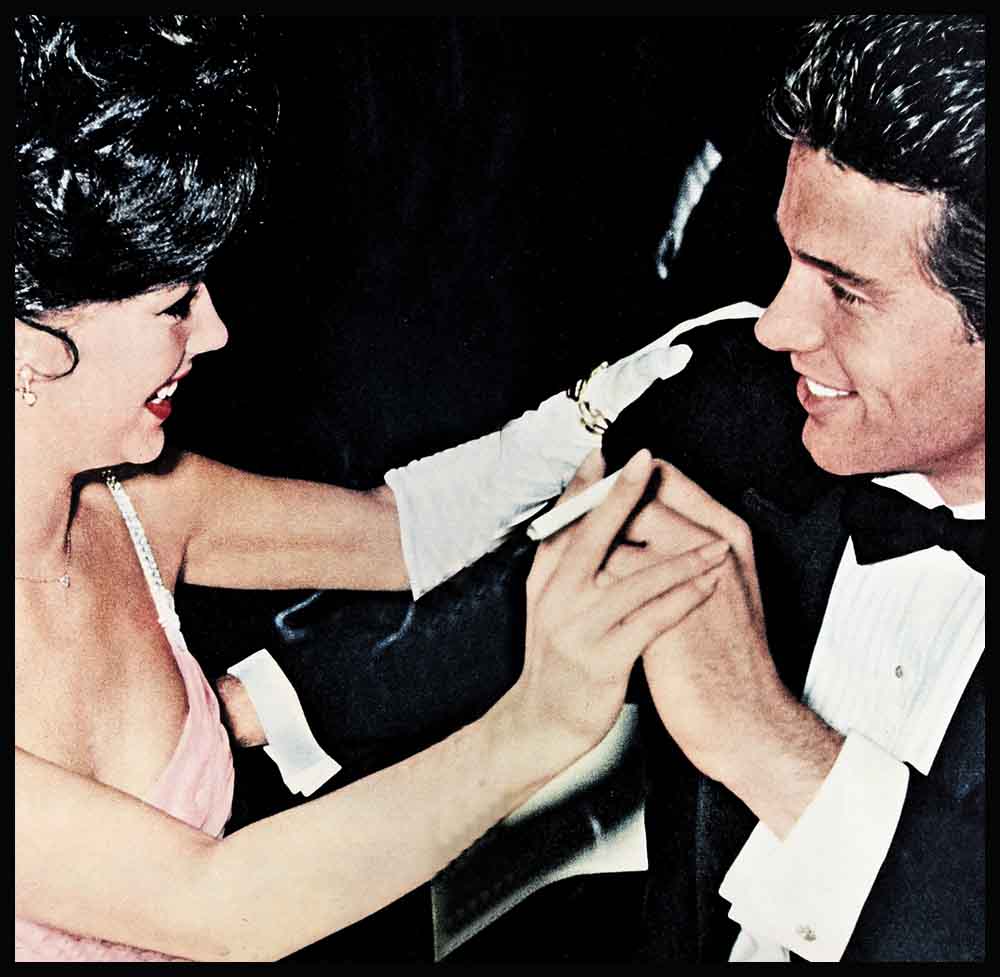

On the set of “Splendor in the Grass,” a fellow and girl, literally sick with love, kissed, touched, fell together before the cameras. Day after day, their love scenes were pulsating and authentic. Members of the crew mopped vicariously fevered brows and watched Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty. It was a warm New York summer, it was torrid on the set. There wasn’t a grip or prop or electrician who didn’t whistle to himself, there wasn’t a person on the set who didn’t feel the flame. One of the people on the set was Bob Wagner, the female star’s husband. One of the people who heard the rumors and flew back to visit was Joan Collins, the male star’s fiancee. Ask anyone who knew Natalie and they’ll tell you that there has never been a girl in this town who wanted so much to make a success of her marriage or thought so surely that she had. But by the time “Splendor in the Grass” was over, the Wood-Wagner marriage was over, too.

On the set of “Let’s Make Love,” a suave, sophisticated man looked into a woman’s eyes as if he knew their innermost secret, her mouth parted, breathless as a girl’s. This is an actress who has been so terrified of acting, so self-conscious and self-critical that there have been times she held up production out of sheer fright. But with Yves Montand, Marilyn Monroe gave everything she had to the part. The kisses were more than passionate, they were evocative, searching, so realistic that hard-boiled technicians were the ones who started the romance rumors. “The red-hottest love scenes I’ve ever seen,” one veteran electrician told me. “Arthur Miller was right there, of course. He was heroic, if you ask me. But this Marilyn was carried away. I’d always thought she was a pretty sophisticated babe. But let me tell you, she came out of those love scenes limp as any high school kid after her first date with her first boy friend.”

Yves said it later. “Some women show you only their outside,” he said, “others show you their deep inside. Perhaps I was too tender, too realistic . . . thought that she was as sophisticated as some of the other ladies I have known.”

But it was later he said that. While the love scenes were going on, he had eyes for no one, ears for nothing but Marilyn. One night they were at a dinner party. Arthur was in London, Simone was in Los Angeles, but absent. Marilyn and Yves wandered about, their attention locked in each other, totally unable to lose the mood of the day’s love scenes.

The romance rumors came straight from the set and everyone denied them. Marilyn had certainly tried to be a good wife to Arthur. He represented everything in life she’s always wanted: brilliance, sensitivity, real theatrical know-how. She was especially thoughtful of him at this era in their lives.

But by the time “Let’s Make Love” was over, so was the Monroe-Miller marriage.

And the Montand-Signoret marriage was barely salvaged by a determined Simone.

Some romances do end tragically because of love scenes; and sometimes other romances begin.

On the set of “Lovers Must Learn” Troy Donahue and Suzanne Pleshette melted into each other’s arms. They never had a date in Rome—there wasn’t time for dates—but the news of their awakened passion again came straight from the set, from the guys who are old pros at movie making and recognize the genuine when they see it. “They were right,” Troy admits. “They knew it before we did. Now we are dating, we are in love, it’s a lovely time we’re living. But they knew it, sensed it, before we’d even realized . . .”

And the camera keeps grinding . . . there are Tuesday Weld and Gary Lockwood . . . Sandra Dee and Bobby Darin . . . and after some cozy scenes in “Can Can” Frank Sinatra began his courtship with Juliet Prowse . . . even Roger Smith and Vici’s romance began when they rehearsed a love scene in Benno Schneider’s workshop. Elvis Presley is susceptible to each new leading lady . . . ditto Rod Taylor . . . ditto Gardner McKay . . . and if not as susceptible, at least as hopeful is Dwayne Hickman. . . . Judy Garland fell in love first with the director who showed her how to play a love scene (Vincente Minnelli), then developed a crush on Fred Astaire which that gentleman never even realized. And then, of course, there was the tough guy of films, Humphrey Bogart. The idea of taking some dame in his arms who was worrying primarily about how her hair looked wasn’t for him. So he shied away from love scenes until he found himself gradually easing into the hero roles. For “To Have and Have Not” he balked like a mule when he found out they’d cast opposite him a twenty-year-old novice, fresh from a fashion model’s job in New York.

Tawny-haired, long-legged, with a cat-like grace and a wide generous mouth, Lauren Bacall showed up on the set one day and they went into their first scene. The twenty-year-old novice had to make a languorous entrance, lean against the doorway of Bogart’s dingy hotel room and inquire, “Anybody got a match?” She had a low, silky sensuous voice. He tossed her the box and kept his brown eyes level. “If you want anything, just whistle,” she said. But he did more than whistle.

He went into those love scenes without the customary aversion. He made no bones about it. He told his wife, Mayo Methot, with whom he’d been battling for some time . . . he told everyone that he was in love with his leading lady and wanted a divorce. “Mayo can have anything she wants,” he said, “if she’ll let me go.” He admitted that he was probably “making it tough on ‘Baby,’ shooting off my big face the way I have; but it’s wonderful to be in love again at my age.”

He was forty-five. He married his baby and they had some wonderful years together. They also made dynamic pictures like “The Big Sleep” and “Key Largo.” Bogey wanted his sultry, forthright bride as his femme fatale, they both felt they could do their best together. And the fans wrote in, “We like to see you two kiss on screen because we know it’s real.”

And there was Joan Crawford and Clark Gable in “Possessed” . . . beautiful together, electric . . . so electric that M-G-M co-starred them in picture after picture. Photographer George Hurrell achieved the most glamorous romantic portraits of his career, not posing Joan and Clark, but merely standing by with his camera in the studio gallery. “Most of the time,” he says, “they forgot I was there.”

As Joan (in her forthcoming autobiography “Portrait of Joan”) writes, “I was in love with Clark but I lacked the courage to live it. I was afraid it wouldn’t last, that every girl who worked with Clark would feel the same way I did.” She also says, “The love scenes you play with actors you don’t like are the ones for which you should receive an Oscar.”

What do other stars think about the dangers of Hollywood love making?

“You have to believe a love story, that’s essential,” Glenn Ford says. “You accept a role because you believe in the characters and in the story. This emotion could happen between these two characters—your job is to bring about reality, create the truth. I never have been able to put on a role and take it off at the day’s end. You become very close to the glamorous, wonderful women you work with.”

Tuesday Weld says, “I’ve played love scenes when I felt nothing. But I’ve also played love scenes where I felt something. Of course they’re dangerous, especially if you are married. But they’re dangerous if you aren’t married too, if you are going with someone who means a great deal to you, someone with whom you have a close relationship. A love scene with another person can confuse you and provide considerable anxiety for him, the man in your real life with whom you’re not doing the love scene. It isn’t a matter of not trusting each other. It’s a matter of nature being nature. You can’t shrug it off as being ‘just work.’ It’s romance—it’s just legalized. I played my first love scene at thirteen, exactly one minute after I’d met Teddy Randazzo on the set of ‘Rock Rock Rock.’ It was a little nerve-racking, but Teddy was attractive and I dated him for quite a while. I’ve dated most of the boys I’ve worked with, because you do find yourself attracted. Later we’ve become good friends—Dick Beymer, Elvis Presley. Not Gary Lockwood, he’s no friend yet.”

“I’m not saying people don’t ever fail in love when they make pictures together,” says Stephen Boyd. “There are people who get to know each other—but I don’t believe it’s because of the love scenes that they get married. They could play a fight scene and probably get married, too. Certainly I date the girls I work with— Dolores Hart, Haya Harareet, Brigitte Bardot—and they are all friendships. The one close personal friend I’ve made in pictures is Hope Lange.”

“I always fall in love,” says Dolores Hart, “not with the person exactly, but with the character he’s playing—usually a charming character, because that’s the way he’s written. I developed a great fondness for Stephen Boyd when we made ‘Sound of Trumpets’ on TV. Then I found myself with him for four months in Europe on ‘The Inspector General.’ Stephen played a joyous and delightful character and I could only react joyously and honestly. We had a wonderful rapport. I only hope it shows on screen what we felt. The only way I could keep my head was to remind myself that I was Dolores, not Lisa, the girl in the picture. This realization has always helped me . . . at least so far.”

Richard Beymer says, “It depends on who the love scene is with. Those first poignant scenes with Millie Perkins in ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’ were possible only because Millie was as shy, as sensitive and embarrassed as I was. It was quite another story with Tuesday. She’s the all American girl, cute, coquettish, round-faced, foxy, sparkling-eyed, witty, with the laugh of a siren and a grasshopper personality. And you’ve never known what asphyxiation can be until she’s practiced mouth to mouth artificial respiration on you for several days without a pause, as in ‘Bachelor Fiat.’ But I’d flipped for Tuesday working on ‘High Time’ and I don’t think that can ever happen to me again. I like Tuesday, we’re friends and she’s a good kid. But she was pretty young then and was bound to gravitate from football hero to basketball champ, like the teenage crowd does. She did me a great service, actually, I found out that I could get hurt and I’ll always be a little wary of love scenes … on screen.”

“If you fell in love with every girl in every love scene you’d go crazy,” says Brett Halsey. “In movies, love scenes can affect a marriage. The most dangerous love scene I ever played was the one with Luciana (Paluzzi) in ‘Return to Peyton Place.’ When we met on the set, we hadn’t spoken in six weeks. For our first words we played a scene in a bedroom which started with a furious fight and ended in a love scene. The story was such a true parallel to ourselves. The girl in the picture was pregnant, Luciana was pregnant. My mother in the picture was against us. In real life it was Luciana’s mother . . . at any rate, it was such a realistic love scene that we were swept up emotionally and tried a reconciliation. But it didn’t last. You see, those things happen, they happen, believe me . . .”

The merry-go-round began in 1896 when Thomas Edison made a one reeler called “The Kiss.” It starred stout May Irwin and mustachioed John Rice in the prolonged kissing scene from their stage success “The Widow Jones.” Members of the clergy denounced this little gem as “a lyric of the stockyards” but it broke all attendance records and movie producers had the clue to what the public wanted.

By 1911 the formula had been improved enormously. There was kissing, yes, but the people kissing were no longer a portly woman and a middle-aged man, they were now the most beautiful people Hollywood could find—Francis X. Bushman and Beverly Bayne. The gentleman with the divine profile and the actress with the soulful eyes struck sparks that sent tingles to the audience spine. They fell madly in love, these two. But love involved a well-kept secret that could hurt Francis’ appeal to fans—he was married and the father of five children! His wife agreed—so he thought—to a secret divorce, but she made it a public one and he was ruined! And even when he married Beverly, those who had adored them as lovers wouldn’t accept them as man and wife.

They were not the only screen lovers to marry. In 1909, two days after teenaged Mary Pickford went to work for D. W. Griffith, he had her rehearse a love scene with classic featured Owen Moore, one of the big male stars of the day. Little Mary informed Mr. Griffith that there would be no kissing, she regarded kissing as vulgar in the extreme. And how did she presume to convey her affection? Mr. Griffith wanted to know.

“By looking lovingly into his eyes,” replied Mary. It must have been a very loving look for she was given the lead oposite Owen in “The Violin Maker of Cremona.” Owen made love to Mary in many pictures and the audience was impressed—it looked like the real thing. It was the real thing. At sixteen, Mary ran away and married Owen Moore, whom she later divorced in one of the first spectacular Nevada divorces. But by that time, she had become a great star and was typed in ingenue roles.

But there weren’t many ingenues like Mary and movie producers were ever on the alert for players who could strike sparks from each other and who could be featured in dramas that centered about love. The epitome was reached with John Gilbert and Greta Garbo.

On screen, Greta’s was a mature sensual-ism such as had never been seen before and a certain haughtiness which increased her sex appeal. Her derisive gaze offered an invitation without responsibility and her films were overnight sensations. When she was offered “Flesh and the Devil,” Garbo refused to come to the studio.

She was tired. she was depressed . . . until director Clarence Brown introduced her to the man who was to be her co-star. John Gilbert was a black-haired, black-eyed son of a gun with gleaming white teeth. “The Merry Widow” and “The Big Parade” had established him as a top screen lover, but with Garbo he truly caught fire. She was the passion of his life and with him she, who had been languid, sad, somewhat anemic, came to vibrant life.

Clarence Brown says, “It was love at first sight and it lasted a long time. In front of the camera, their love making was so intense it surpassed anything anyone had ever seen, it made the technical staff feel their mere presence an indiscretion. In a love scene they seldom heard when I called cut.”

Everyone knew that Garbo and Gilbert were madly in love, and “Flesh and the Devil” established them as the most ravishing lovers since Tristan and Isolde. Seeing them together was like eavesdropping on their private life. Everyone in the world knew that Gilbert hoped to marry his beloved, that he’d built a magnificent home for her and purchased a luxurious yacht, “The Temptress” on which twice they sailed away, object matrimony. At least Gilbert’s object. But Greta wavered . . . not for lack of love but for lack of assurance that she could make it work.

They were very different people temperamentally. Gilbert was volatile and gregarious, he loved being a star. She was by nature solitary, supersensitive and terrified of the limelight. But resist him she certainly could not. In “Flesh and the Devil” she had kissed him with an open mouth, causing a sensation publicity-wise and the sensation continued through “Love” and “A Woman of Affairs.” Gilbert and Garbo became supreme symbols of sex on the screen and left their impress on each other’s life until his death.

Lovely Loretta Young, padded out in vital places to look more grown-up, celebrated her fourteenth birthday on the set of “Laugh Clown Laugh” and ran into her first problem when the director yelled, “Look into your mirror. You see your lover . . . you’re mad about him . . . make it sexy. Okay, let’s go.”

Loretta nearly burst her chest, heaving to show emotion. The more she’d heave, the more tough director Herbert Brennan would shout. Finally, screen lover Nils Asther took the little girl aside.

“Loretta,” he said, “when you see me in the mirror, dear, don’t heave. Just look at me and imagine I’m a hot fudge sundae.” And it worked.

But if, at fourteen, she thought of each screen lover as a hot fudge sundae, by sixteen she switched techniques. The picture was “Two Lover s,” the actor Grant Withers, Loretta fell in love and on her seventeenth birthday eloped with him to Yuma, a rash impulsive move against her mother’s advice—as Mary Pickford’s first marriage had been against her mother’s advice. The mothers knew that love scenes are dangerous—but the daughters played them and took the consequences. For some ten months Loretta and Grant played at housekeeping in their little apartment, then the marriage was ended. This was the first in a series of screen romances that left the romantic Loretta heart broken.

Her name was linked with that of almost every eligible young man in Hollywood: Clark Gable, Tyrone Power, David Niven, George Brent, Jimmy Stewart, director Eddie Sutherland, director Joe Mankiewicz. But the fact is that at this time, Loretta was tragically in love with an actor with whom she’d played a poignant love story and who couldn’t get a divorce. Everyone in Hollywood knew, but not a word was printed. The press had nothing but admiration and sympathy for a girl “who never did hide her emotions when they were genuine or her happiness when it was overwhelming.”

So long as the cameras turn, the love game will go on. No matter what is going on in a star’s private life . . . loneliness, emotional insecurity, marriage problems . . . that star walks onto a movie set and into the arms of a beautiful stranger who has a marvelously magnetic attraction or he or she wouldn’t be on the screen in the first place. And the stranger isn’t a stranger, really, because he or she is playing a part in a script where a relationship is ready-made.

Some stars insist they can convey a character without emotional wear and tear on themselves—but that’s rare. Most stars become the character. . . . Well, lips are lips, a clinch is close and warm. . . . And when a star starts a new picture, he or she may be opening the door into a new heaven . . . or into hell.

And fame, fortune and publicity can’t take the place of individual human happiness. Ask Marilyn. Ask Natalie.

Natalie has said, “Love is the most important thing there is. I don’t see how people can exist without love, let alone work without it.”

Well, some of them work with it and work well. But it’s playing with dynamite, and that spells danger!

—JANE MORRIS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1962

gralion torile

21 Haziran 2023Absolutely pent content material, regards for information