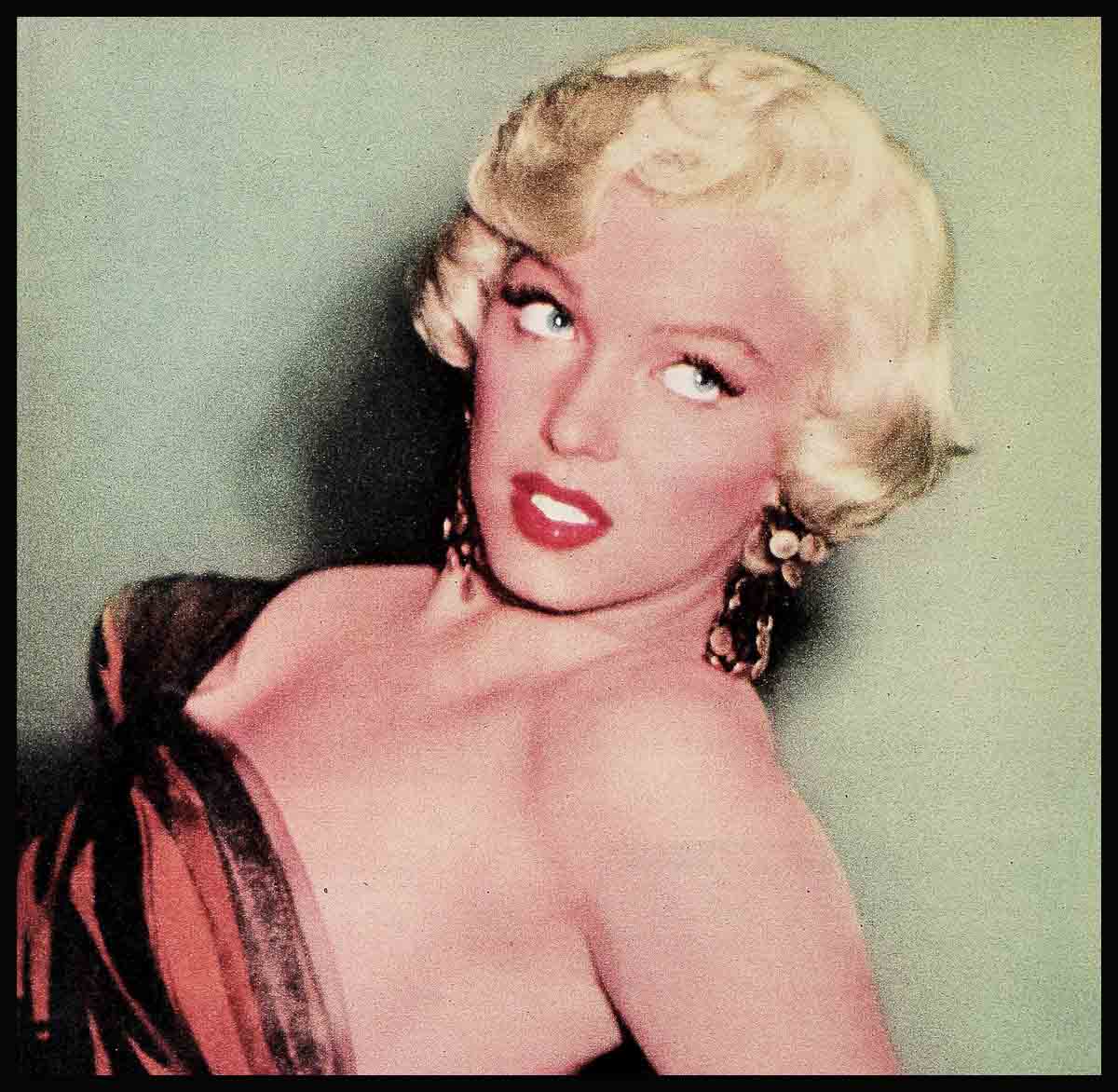

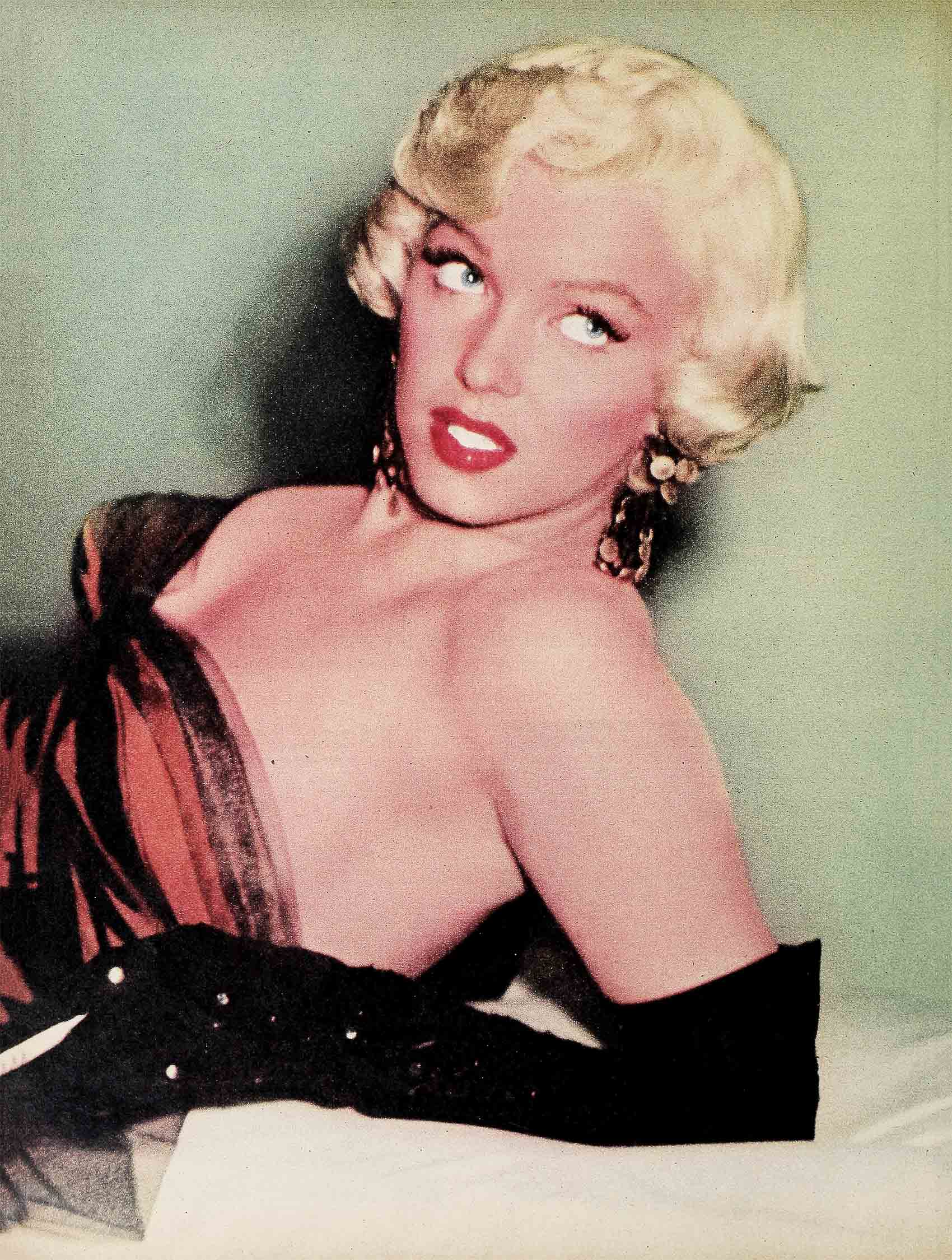

Marilyn Monroe: “Don’t Call Me A Dumb Blonde”

When director John Huston gave Marilyn Monroe the role of a dumb, delicious blonde in The Asphalt Jungle, it was ai considered a classic example of type casting. I, At that time, five years ago, the film colony did not hold Marilyn‘s ability in high regard.

After starting at $75 a week, she had been dropped by Columbia, Gene Autry, 20th Century-Fox and several independents.

She was recognized as a close friend of famous agent Johnny Hyde, but her acting talent was judged to be minuscular. Her vaunted anatomical measurements were considered no better nor worse than those of a hundred other aspirants to the screen.

Today, all that has been changed. Marilyn Monroe is considered a credit by Hollywood. She is regarded as one of the most dynamic box office attractions the movie industry has ever known.

She is being labeled, “a thinker . . . a shrewd one . . . a doll who’s dumb like a fox . . . a talented artist . . . one girl who’s handled herself well in the Hollywood jungle” and “probably the most valuable property in the movie game today.”

Talk of Marilyn, however, is not one-sided. There is a small shrewd group that insists that the curvaceous blonde “is mixed up . . . is suffering from delusions of grandeur . . . will never make any man a happy wife . . . has been following poor advice . . . has more luck than talent” and “should never have gotten into any contract beef with her studio.”

Regardless of how you personally feel about Marilyn, the indisputable fact is that she has ip developed from a nonentity into the most widely-discussed actress in America—and one of the most admired. The reason is that Marilyn became a star in the face of incredibly tough handicaps.

To begin with, she had no parental guidance, no background, no money, a minimum education, no influential friends. She had a series of unbelievably bad breaks.

For example, after Marilyn was placed in The Asphalt Jungle, her name was omitted from the cast sheet. When the picture was “sneaked” at a neighborhood theatre in Los Angeles, the reaction cards showed that dozens of people asked about the “dumb, well-built, baby-faced blonde.” They had enjoyed her performance, and they wanted to know her name.

Ordinarily, this tip-off is enough to make any studio sign the actress in question. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer declined to do so because of Lana Turner. Five years ago, Lana was the sex appeal champ, and the Metro executives saw no point in arousing her antagonism—not that Lana has a jealous bone in her body—or fostering internecine warfare. The result was that Marilyn Monroe got her walking papers.

She was heartbroken. At the time, she said, “Everyone says I was pretty good in the picture. Was I really?”

“You were great, Marilyn,” she was assured. “Absolutely great.”

Choked with self-doubt, Marilyn asked in a petulant tone, “Then why didn’t they give me a contract or another part?”

“Just the breaks,” she was told. “Just the breaks. This is a rough racket.”

Another director, Joe Mankiewicz, then rescued Marilyn from her psychological depression. He chose her for another dumb blonde role, in All About Eve.

When Darryl Zanuck saw the rushes on Eve, he ordered his casting department to give Marilyn Monroe a contract.

“We had her for a year,” he was told, “and she can’t act. She tries hard but she can’t act.”

“Sign her,” Zanuck ordered. Marilyn signed a seven-year contract in August, 1951. She was cast in a series of minor vehicles and her build-up was delayed. The reason for the delay: Betty Grable. Not that Betty ever muttered a single word about Marilyn. It was just that Harry’s wife was then the studio’s number one star, and there seemed to be no point in threatening her position.

In 1951 Marilyn was assigned inconsequential roles in As Young As You Feel, Let’s Make It Legal and Love Nest, and loaned to RKO for Clash By Night.

RKO paid 20th Century-Fox $6000 for the loanout. Two years later they offered $250,000 to borrow Marilyn for the lead in High Heels and were told, “Monroe is not available for a loan-out at any price.”

Marilyn had achieved such great success in Clash By Night that her own studio was compelled to recognize her, Betty Grable or no Betty Grable. In 1952 she was cast opposite the leading male stars in the studio’s leading productions.

This background is necessary for understanding the feud that developed between Marilyn and her studio when she finished The Seven Year Itch and There’s No Business Like Show Business.

This feud—let’s call it a dispute—began when Marilyn married Joe DiMaggio. Marilyn, for the first time in her struggling life, knew a modicum of financial security. She had a husband to support her. She didn’t have to work.

She therefore announced that she had no intention of making a film called Pink Tights. Whereupon the studio hired Sheree North to replace her. Marilyn also let it be known that she was dissatisfied with her old contract that was then paying her $750 a week when she worked.

Agreeing that she deserved more money, the studio consented to abandon the old contract and offered a new one calling for Marilyn to make two pictures a year at $100,000 per picture. After three and a half years she could make outside films.

Subject to discussion with her lawyers, Marilyn went into Show Business and The Seven Year Itch on those terms, drawing $1500 a week against $100,000 per picture.

When The Seven Year Itch was finished, Marilyn, having dropped Joe DiMaggio, began to go around Hollywood with a New York photographer named Milton Greene.

“I met Marilyn about a year and a half ago,” Greene says. “When I came out to Hollywood on my honeymoon a little while later, I introduced my wife Aimee to Marilyn, and we all became good friends. I shot a lot of pictures of Marilyn—they’re going to be published in a book—and I invited her to spend Christmas with us in New York and Connecticut.

“I introduced her to my lawyer, Frank Delaney, and she told him what was on her mind. That’s how we started Marilyn Monroe Productions, her own corporation. Marilyn wants to be able to have some say in the roles she plays. All this stuff about her wanting to play the female lead in The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoievsky, is a bunch of bunk. She was misquoted. A line of what she said was taken out of context.”

Marilyn said, “Technically, I’m not under contract to 20th Century any more. But I like the studio, and I want to make more pictures here. And I think we can work it out. I’ve been quoted as saying that I don’t like the pictures I’ve been put in. I never said that. A couple of the pictures might have been better. I suggested that a very good role might be the female lead in The Brothers Karamazov, and right away it was taken for granted that I was getting arty and wanted to play the part.”

Asked if there was any chance of her reconciling with Joe DiMaggio, her answer was, “We’ll keep on being very good friends.”

Then she was asked if her attitude had changed, generally speaking, and she said, “I don’t think so.”

But the truth Is that since her divorce from Joe DiMaggio, Marilyn has come out of her shell. She no longer seems insecure, inhibited, shy or afraid.

She has reached that critical point in her life where she must decide which is more important, career or wifehood. And her answer right now is career.

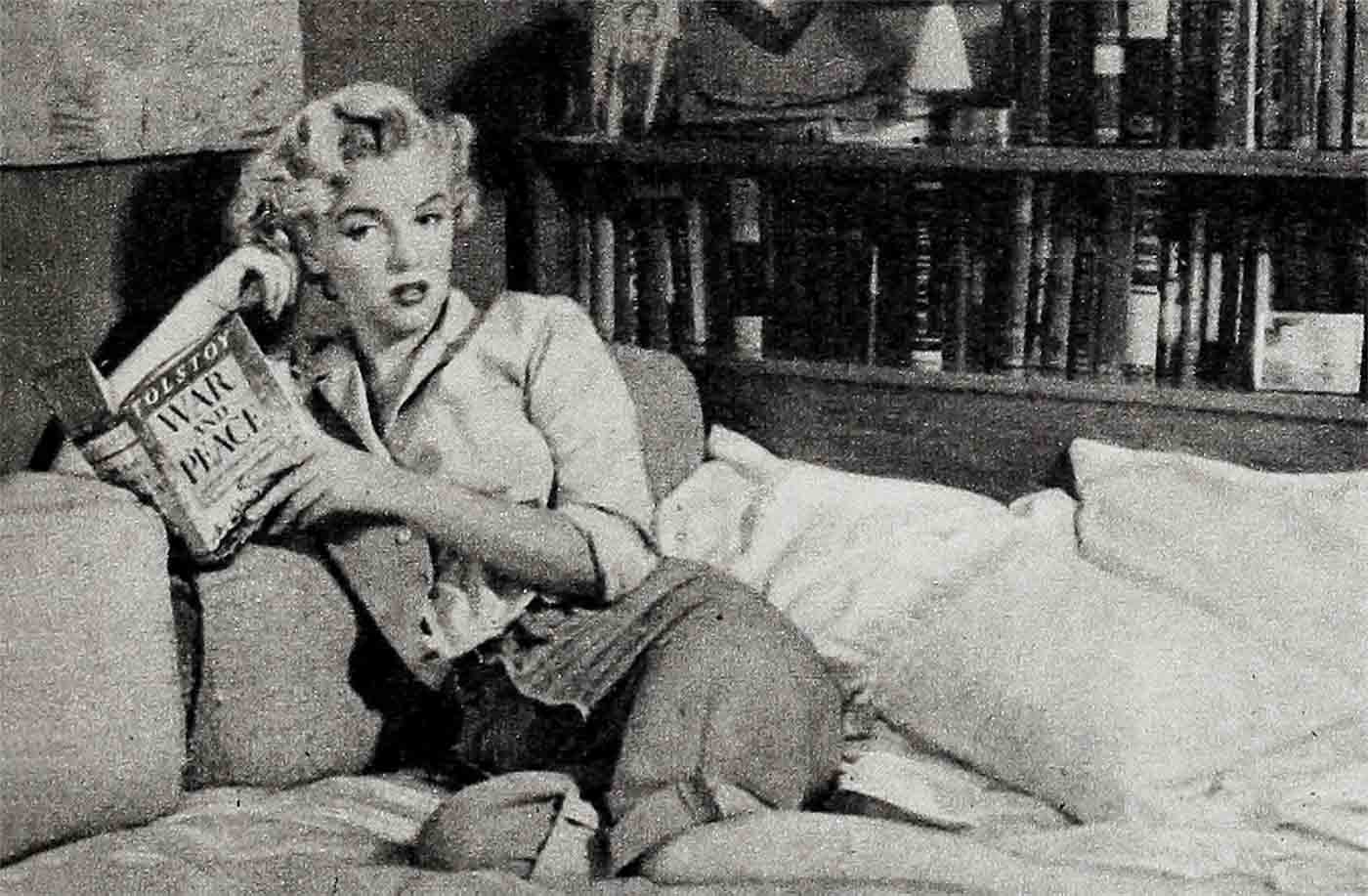

Marilyn isn’t money-hungry. But she is quietly determined to get some lucre while the getting is hot. No actress deserves it more, because there is no actress in Hollywood who has worked harder than Marilyn Monroe at learning her trade. The hours, the weeks, the years she has put in with her dramatic coach, Natasha Lytess, studying lines and movements— “You wouldn’t believe it,” she once said. “It’s been the only thing that really mattered.”

Five years ago Marilyn Monroe knew precious little about dancing, acting, music, literature or clothes. She suffered from a complete inferiority complex. One columnist used to aggravate the complex by writing, “When will Marilyn Monroe stop dressing like an unmade bed? This girl shows everything in her clothes except good taste.”

Hungry for the education denied her by circumstance, Marilyn has spent practically all of her spare time reading widely, listening to good music, taking singing lessons and learning the financial facets of the motion picture business. Marilyn has learned that highly taxable salaries are not nearly so rewarding as capital gains or profit-sharing deals. She looks around Hollywood and sees that Jimmy Stewart has garnered more than $4,000,000 in the last six years by working for a small salary and a large share of the profits. She knows that Gable is going to get at least half a million from Soldier Of Fortune. Cary Grant, June Allyson, Alan Ladd are all independent free-lance operators. Why can’t she be one?

Her New York lawyers claim that she is. They told her weeks ago that when 20th Century-Fox sent her a letter saying they were abrogating her old contract and drawing up a new one, she was free so long as she didn’t sign the new contract.

The studio, on the other hand, claimed that if Marilyn didn’t sign the new contract, then the old contract was in force.

Regardless of the contract dispute, Marilyn wants a degree of professional independence, because she feels strongly that she will know what to do with it. At twenty-eight she is willing to strike out on her own. Although her studio regards her in a jaundiced light, Hollywood respects her sagacity and understands her desire for independence.

Marilyn has practically no close women friends, but one woman who has known her for years recently explained her status.

“These last few years,” she claims, “Marilyn has grown up. She may not think so, but she’s changed a lot. From a bewildered youngster she has developed into a movie star with poise.

“She feels that she is no longer a dumb blonde. In many quarters there is no recognition of her growth. Many men in Hollywood remember her as an avid, struggling kid with a well-turned body and a seemingly empty head. They remember her when she didn’t have a dime, when an interview frightened her silly, when she had to be rehearsed over and over for a simple bit of subtle playing.

“Many of these men created or helped create the Marilyn Monroe legend. If Marilyn said something artlessly funny, they’d broadcast it all over the world. For example, when Marilyn was asked if she had anything on while she was posing for her famous calendar, she answered, ‘I had the radio on.’ That remark was planted in every column in the country.

“As a matter of fact, Marilyn’s publicity build-up was so tremendous that sometimes it got out of hand. The Clark Gable incident is an illustration. Because Gable danced with her at a party, an attempt was made to blow it up into a full-fledged romance. People laughed, and Darryl Zanuck gave orders to go easy on the Monroe publicity.

“Marilyn has earned a good deal of money for her studio. Everyone recognizes that. But she herself has practically no money saved or invested. Her salaries have been relatively small and her expenses high. But money is not the primary interest in her life.

“More than anything else, she craves recognition as an artist, as an actress—not as a lucky, fatuous personality. She would like to cremate the ‘dumb blonde’ reputation she never deserved.”

There is a world of difference between “dumbness” and “naturalness.” Marilyn has always been natural and candid.

Once, she was asked what, if anything, she did to maintain her posture. She admitted quickly, pointing to a set of dumbbells, “I lift weights to fight gravity. Gravity makes you sag.”

Questioned about her sexy voice, she said, “I never find it necessary to use my voice in any special way. If you think something sexy your voice just naturally goes along. I’ve given pure sex appeal very little thought. If I had to think about it I’m sure it would frighten me.”

On the subject of clothes she said, forthrightly, “I dress for men. They say women dress for women, but a woman looks at your clothes critically. A man appreciates them.”

Marilyn never has been credited with much wit, but reporters who have interviewed her over the years will tell you that she is one of the wittiest girls in the film colony—not a smart-alecky wise-cracker, but an actress who is endowed with a natural sense of humor.

“So many reporters,” Marilyn once complained, “ask me something. Then when I answer they say, ‘Gee! I can’t use that.’ One time a fellow asked me what I wore to bed. So I said I only wear Chanel Number Five. ‘Darn it,’ he moaned, ‘I can’t use that.’ ”

Despite her naiveté and her charming frankness, despite “the dumb blonde” legend planted and nurtured by jealous women, Marilyn Monroe has always had a good head on her shoulders.

If she hadn’t she never would have survived, much less succeeded, in Hollywood.

At a party for her at Romanoff’s the Hollywood greats—Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, Bill Holden, Claudette Colbert, Doris Day and many others—came to Marilyn’s table and said much the same thing: “I hear that in The Seven Year Itch you’re absolutely wonderful.”

Five years ago, Marilyn would have blushed and mumbled a shy, “Thank you.”

But now Marilyn smiled beautifully. “Thank you,” she said. “But it’s really Billy Wilder’s picture. He’s a great director, and he makes me look good. In fact, so good that I want him to let me play in his next picture. But his next picture is The Lindbergh Story, and he says I can’t play Lindbergh!”

THE END

—BY ALICE FINLETTER

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1955

No Comments