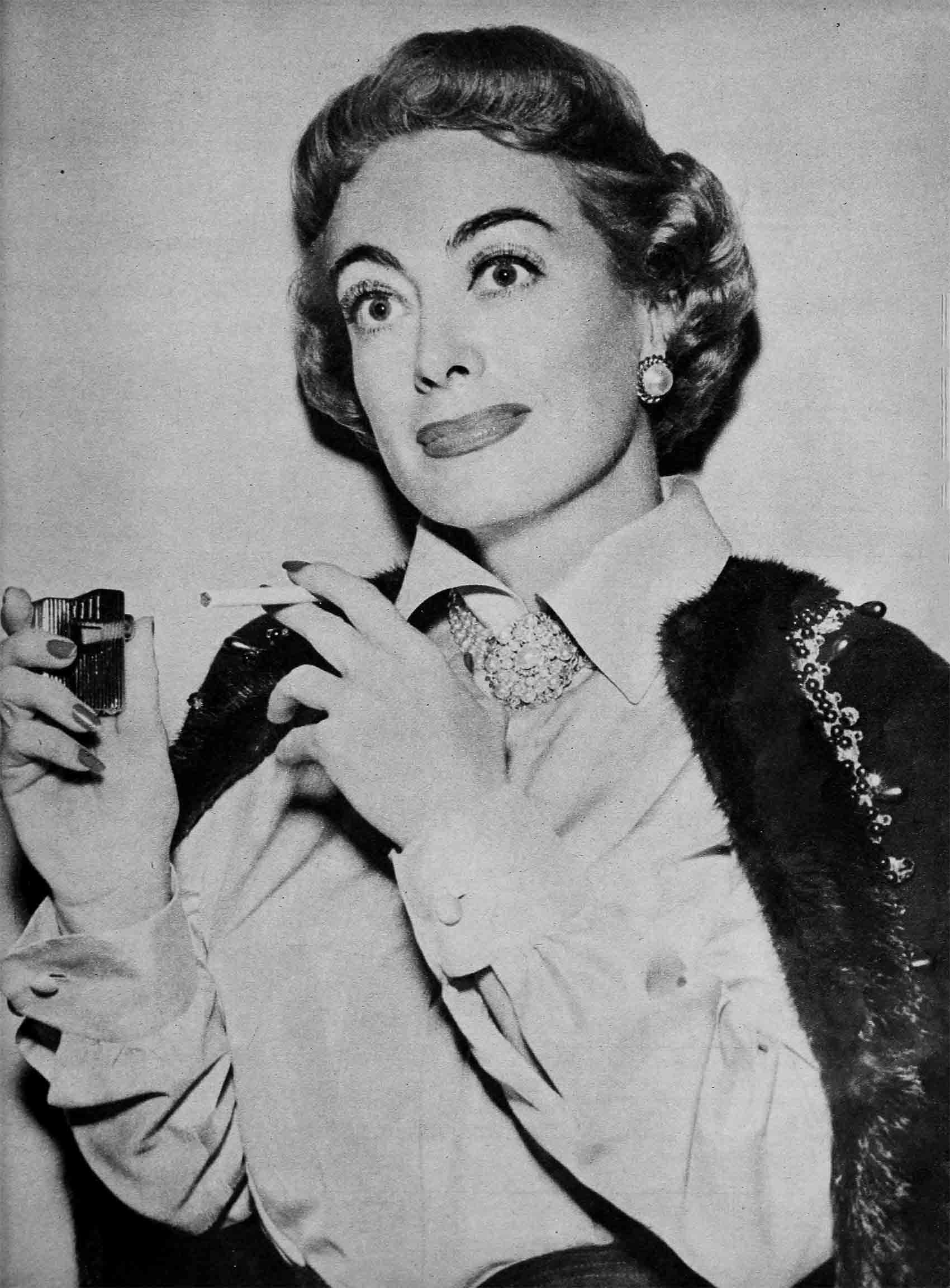

Mistakes That Made Her Famous—Joan Crawford

“It is good to battle, to suffer, to be thrown overboard and left to save ourselves. What we lose in comfort, we gain in energy—and energy is the most precious of man’s weapons.”

So wrote a man named Wagner a number of years ago. History does not record whether or not his observation knocked his audience as a whole into a spin. But it did induce in Joan Crawford an excited pang of recognition. She wrote it down in one of a number of leather-bound volumes in which, for 15 years now, she has been recording similar capsules of residual wisdom.

In the same manner, she has seen eye-to-eye with a Mr. Irving: “Love is never lost—if not reciprocated, it will flow back and soften and purify the heart.”

And with a Mr. Moore: “The difficulty in life is the choice.”

The difficulty, indeed. Probably there should be some journalistic ethics against gamboling up to a person of Miss Crawford’s professional stature, dignity and beauty, and saying: “You’ve pulled a few rocks in your time, haven’t you, pal, and if so, what were they?” To Miss Crawford’s everlasting credit, she did not bridle. She laughed. Laughter should be a musical sound at all times but quite frequently it is not. Miss Crawford’s though, is at least as pleasant to listen to as any in Brentwood Park, West Los Angeles, California.

“Pulling a rock” is sports page patois for making a mistake. Make enough of them and you call it experience. (Oscar Wilde—roughly.)

AUDIO BOOK

“Wilde was a true cynic,” said Miss Crawford. “Bitter, too. What a criminal waste of time, being bitter! Where is the point? Curling up with a—a cud of misery! Mistakes add up to experience only if you profit by them. But then they are experience, whatever Wilde may have thought about it.”

But she had made them?

“Do I seem to you to have divine attributes? Of course, I’ve made them. I’d hate to count. I’ve made them and I’ve tried to learn from them, but if I had to do it all over again, I’d make the same ones, because I am what I am. A fresh start wouldn’t change me. I’d be little Lucille Le Sueur just as I was before, the same weapons, the same frailties. Mistakes! Oh, yes.”

And would she specify?

“I’d rather generalize. You can see the reason for that, can’t you?” It was a very hot day in Brentwood Park, West Los Angeles, etc. Most unusual. There were parboiled publicists at the bottom of Miss Crawford’s garden, and another interrogator waiting to come to bat. Here on the east patio of the lovely home that is in a constant state of growth or flux, there were exterior evidences of homework well done—or so one could surmise. In the past, Miss Crawford has been charged by critics with being rather vociferously over-groomed. She wore a simple cotton dress now and she had kicked off her shoes. She has been scored, as a matter of record, with being on occasion oppressively regal in bearing, the Movie Star in spades. It may once have been so; it is not so today. She is amiable, humorous and self-deprecating. It has been said of her that her public utterances are, or were, painfully contrived. On the contrary, she is, with the possible exception of Humphrey Bogart, the warmest, most candid and unguarded lip in Hollywood. Her friends in the press—and the press is very fond of her—tend to protect her for her own good. Miss Crawford underwent several nasty jolts before she learned the efficacy of the off-the-record pronouncement. Now she says, “No more talking off the record.”

Another, much lesser, actress had that morning sounded off for a wire service on the subject of men in general. Men in general were foul balls. Wasn’t that a corollary instance of indiscretion?

Miss Crawford grinned, a facial contortion not permitted many women, but on her it looks good.

“Very corollary,” she said. “But maybe she has another reason for not liking them. I hear she smells a bit—uh—musky.” There was a moment’s tight silence, then strangled laughter. “Oh, no!” said Miss Crawford. “Tie me down and gag me before I—Dear heaven, where were we? Quick!”

“Generalize.”

“Generalize. All right. You understand, I can’t talk about my mistakes in terms of my husbands. Wouldn’t if I could.” Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Franchot Tone. Phil Terry. “They were fine guys. From each of them, I—oh, you know. Let’s not sound as though I milked people for what they had to offer. They were fine guys, period. And I don’t want to talk about the pictures I shouldn’t have made because there we’re involving directors or writers or producers or all three, and what’s done is done. I’m not blameless, either, not by a very long shot. You know something, when I make a good, solid bloomer, like a picture a while ago that shall be nameless, it’s because Ithink about the thing. I reason. With me, that’s apt to be fatal. If I don’t go by instinct, I’m wrong nine times out of ten. By instinct alone, I bat anyway .500, maybe a little better.

“But in general, my greatest mistake, only it’s more a failing than a mistake, is wanting so desperately to be liked. That doesn’t make me unique, I know, but I work too hard at it. I—I seem to need friendship, not just enjoy, but need it like a plant needs water. I go overboard and press, and it makes people wary. I don’t know, I think they’re thinking, ‘What’s this?’, and sometimes they shy away, and I know what I’m doing wrong but then I can’t help it; the momentum’s established. Friendship should come easily and naturally and even casually; I know that but I don’t feel it. You understand? Ive driven off people by just the intensity of my need for their affection. Isn’t that funny? No, thats not funny. Not to me. Listen, I don’t sound pathetic, do I? I’m not pathetic. I’m a certain way, that’s all.”

The leather-bound book lay open on Miss Crawford’s lap, the adopted conclusions of her elders painstakingly assembled in her own slanting hand. An educator who had greatly influenced her formative thinking had made his contribution, and she had noted it and stuck with it with rather touching accuracy and faith. “The world,”(she must have written from memory or dictation), “is not interested in your troubles. When your problems are the deepest, let your laughter be the loudest.”

“Not pathetic,” said Miss Crawford. “Please not pathetic. All right, here’s another. I’ve mistaken opportunists for friends. Let’s be sure and get that one straight. I have to use a label I don’t like to use. Movie star. But I don’t mean myself, Joan Crawford, as a movie star, big wheel, anything like that. A movie star, however much she herself may happen to contribute to the process, is really in the end the product of a system. A—there’s a good word for this—a—a happenstance. A happenstance. But a movie star is a fact, too. And as a fact, a movie star is an exploitable asset. Mmm. This is one of my really glib days. So anyway, men would call me and want dates, but not with me and not even with Joan Crawford, but with a movie star, and only for the good it would do them, for a career boost or a little publicity or what have you. Frankly, it’s not very flattering. I’ll be franker than that. It’s a little nauseating. I like guys who call for dates and I respect actors who look for jobs. But I wish they would make it two separate phone calls.”

It should be noted here that Miss Crawford’s voice was neither plaintive nor querulous. Evidently she had simply come to a conclusion and then thrust it behind her. “How active,” Miss Crawford had written in her book, copying laboriously a random thought of Alexander Pope’s, “springs the mind that leaves the load of yesterday behind.”

Joan Crawford is a load-leaver of considerable adroitness and strength. (“I never look back! Never, never!What can be more stupid?”) The motion picture industry calls her tough and it calls her shrewd, but with vast respect and in many cases actual affection. The jungle learns to appreciate and sometimes to love its own. Nobody ever thought she had it terribly easy, although that is a biographical phase she does not dwell on. But neither has anyone felt she wasn’t capable of protecting herself in the clinches. She has once in a while taken something of a beating from the ringsiders but like any good pro fighter, she hasn’t let it distract her.

Or maybe she has—a trifle. It’s her business. In lieu of direct comment, she underscored in the book a borrowing from Voltaire and read it aloud with somewhat more feeling than she had accorded the rest:

“I envy the beasts two things—their ignorance of evil to come and their ignorance of what is said about them.”

Well, Miss Crawford shouldn’t feel too bad about this. She does better than par for the course. A fast but thorough piece of research in support of this essay would indicate that among things said about her are these: She’s honest, good-hearted, and generous to a fault. Her professional courtesy is impeccable, and she has many of the virtues customarily supposed to be limited to men, such as forthright willingness to acknowledge error where she is wrong.

But let us say that she is, by her own necessary lights, tough. Who wants to be used, maneuvered or exploited? Who wants to bite for the same dodge over and over again? That’s where Cliquot comes in. Cliquot, in fact, did come in, right about then. Cliquot is Miss Crawford’s poodle, smart even for a poodle and poodles are the nuclear physicists among dogs. Miss Crawford is unreservedly devoted to Cliguot. In her heart, he may occupy second place to her four adopted children. He may. Cliquot came in, offered a rubber ball in an advanced state of deterioration, was fussed over mightily, and went away again. There was something faintly moving in the scene, as there is in the scene of any person with fame, influence or authority in the presence of his dog.

“Here’s a third thing,” she said. “And this may be the greatest mistake of all; I don’t care what I said to begin with. I’m too honest. You’ve heard people say they’re too honest but give it that tone that means they want you to pat them on the head. Not me. There’s honesty and honesty but you can learn to temper bluntness. Yow can. I can’t. If my friends make mistakes, I have to run and tell them about it. Believe me, it’s a form of well-meaning helpfulness that’s likely to get you strictly nowhere. But strictly. Mistake? It’s a mistake all right. Sometimes I think anything that costs you a friend is a mistake, me some.” And that has cost me some.”

Evening was coming on now and the air cooled a little. Miss Crawford leaned back in the lounge chair and her slightly tense face with the matchless bone structure assumed a kind of repose. She closed her eyes and for a brief moment looked tired. Was she?

The much-caricatured eyes opened wide again. “Do you know what they call me? They call me ‘The General’. I’m not tired. I sleep two hours a night. Never any more. Being tired must be a little like dying. Here. Read this.” It was a jotting in the book from a gent named Clark, who had felt it incumbent to declare: “I have lived to know that the secret of happiness is never to allow your energies to stagnate.”

But on two hours sleep a night?

On two hours sleep a night! need. is such a big deal to me. brings, you know, it’s exciting. I can’t remember any one day when there wasn’t something, something!” Edison, next to Miss Crawford, was a sack hound. “I go to bed fairly early but I read and read, and I’m never asleep before four or four-thirty. Then up early, and so forth. Truly, it doesn’t bother me.” And truly, she didn’t look as if it did. The momentary dropping of the lids had passed.

When MODERN SCREEN walked in, Miss Crawford had just finished a high pressure conference with agents and writers apropos a script. Daily these were going on and on and Miss C. was surrounded by omniscient males, some of whom had begun to get her goat.

“Some of the men I work with resent a career woman!” she pronounced suddenly, “in the same way they resent a woman with a sense of humor! It’s an impingement on their egos, in case you can spell ‘impingement’. I could make it reflection. They sit around and I can practically hear them thinking: ‘Now, now, dear, you’re only a woman. We know what’s best.’ So many are like that. The loyal opposition. Well, bless the opposition’s hearts. I don’t know what I would have done over the years without enemies. They’re like a home. Beloved enemy! Who said that? It doesn’t matter.”

She was not, then, affronted by enmities?

Women do not snort but Miss Crawford came reasonably close to it. “Affronted! The book, darling, the book. Right—there!” Right there was this: “He that wrestles with us strengthens our nerves and sharpens our skills. Our antagonist is our helper.”

She put the book back beside her. “You’re going to ask me in a minute why I don’t give up the battle and retire. I can see it in your kind, blood-shot eyes. It’s a look I’ve learned to recognize. She’s had fame, had success, had career, family, home, now why doesn’t she sit back and take it easy? How much ambition, how much anxiety, does one person want or need? Oh, yes, you were, weren’t you? Well, great heavens to Betsy, why should I retire? I’m geared to this sort of thing, I love work!”

Did the book contain a rule of thumb to cope with that one?

“I don’t live by the book, darling. Not the way you mean it. By my book, yes. This is my book, remember. I didn’t compose it but I collected it. It’s me. Wait a minute. Uh-huh. Here it is.” It was by Kahlil Gibran, a name somehow suggesting it might spell something backward. It went: “To love life’s true labor is to be intimate with life’s innermost secret.”

“Besides,” said Miss Crawford, “what would I do if I retired? In a month they would find me down there beside the pool with moss up to here. Breathing but immobilized.”

AS time was running close, and what in the world had ever happened to those mistakes we had started off with so bravely? Remember the plot?

“Oh, those mistakes,” said Miss Crawford. “Those mistakes, I mean. They’re still there, darling. Made. Rooted. I could never call them back and I’d never want to. And Id do it all over again. If I didn’t, it wouldn’t be me. You can see that, can’t you? And a ladylike phooey on Oscar Wilde. This I like better.” The book was all but inexhausible. “A man,” Miss Crawford had written, “can learn twice as much from defeat as he can from victory.”

The California twilight was getting in its licks in earnest now.

“You know,” resumed Miss Crawford presently, apropos some privy thought of her own, “what a sad thing is? It’s a sad thing that we’re always too young to appreciate our parents. By the time we do appreciate them, it’s too late. It’s one of the very few things that are too late. Most things aren’t too late at all. Never look forward, never look back. That definitely is for me. Or forward just a little. Listen: “This day will bring some lovely thing. I say it over each new dawn. Some gay, adventurous thing to hold—and so I rise and go to meet the day with wings upon my feet.”

On two hours sleep? No kidding?

“On two hours sleep.”

A woman of remarkable nervous and physical stamina. With few if any qualms.

“Oh, some qualms,” said Miss Crawford. “I believe in omens. Like a few months ago, I enrolled for a course at UCLA. The very first night, there was an earthquake. You remember the earthquake. I went home and didn’t go back again. I’d had it.” Miss Crawford laughs low in her throat. “Nothing in the book about that.”

A mistake, then?

“An act of God. I made the mistakes.”

And would not unmake them if she could?

“Right. Could not. But would not if could. How horrible to lead a perfect life. How uninstructive. If you’ll forgive a little homespun philosophy, aren’t we all the sum total of our mistakes? Among other things? No, no, I’d do it all over again. That was what you wanted to know to begin with, wasn’t it?”

That was it.

“And now you know.”

She is an incredibly beautiful woman, this one, who apparently has bitten into life quite a lot harder than most have the guts to do. Also, and not quite incidentally, she is an avid admirer of guts, guts of all kinds and guts as evidenced by anybody. That is one of the most clearly defined of the standards she lives by. You would know it without, so to speak, knowing it. Her look is level, her voice strong, her personality incisive to the point of being slashing. Indeed this is a trademark, as all filmgoers must be aware.

She enters a room like the edge of a buoyant sword. Whatever has hurt her—and reputedly she bears a wound or two—the scars are skilfully sutured over. Her friends, however, figure her a certainty to be hurt again and maybe seven or eight more times after that. She has a vulnerable streak there, which, in character, she would have to deny. It has to do with her great propensity for giving and her singular bad luck, on known occasions, of not getting back. However widely sung the joys of generosity, its purveyors are oddly susceptible to the shrug of the ingrate, whose doubtful favors have been likened by Shakespeare to winter wind. Those closest to Joan Crowford suspect she’d save herself pain, if she stopped proffering gifts of the spirit and locked up the vault. It is here the lady herself has to snort again but The Book, her own, betrays her. In it, she has inscribed in a place of honor an especially favorite utterance, stunningly Christian in sentiment but hardly the stuff of realism for an avowed General. Read it and see for yourself how tough she is:

“I shall pass through this world but once. Any good thing, therefore, that I can do, or any kindness that I can show any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer nor neglect it, for I shall not pass this way again.”

Amen, General, but keep the storm cellar handy.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

(Joan Crawford will be seen soon in Torch Song.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1953

AUDIO BOOK

No Comments