Don’t Be A Teenage Misfit—Kim Novak

It took Kim Novak thirty minutes to walk from her dressing room to the set of “Pushover” the first morning the film was scheduled for shooting—a distance of no more than 200 yards. To Kim, the distance was not the problem. What bothered her was an entirely different matter.

“There I was,” says Kim now. “I couldn’t move. I just sat in my dressing room glued by fear. Every time I whipped up enough courage to step outside the door, I almost died when I saw all those people on the set.”

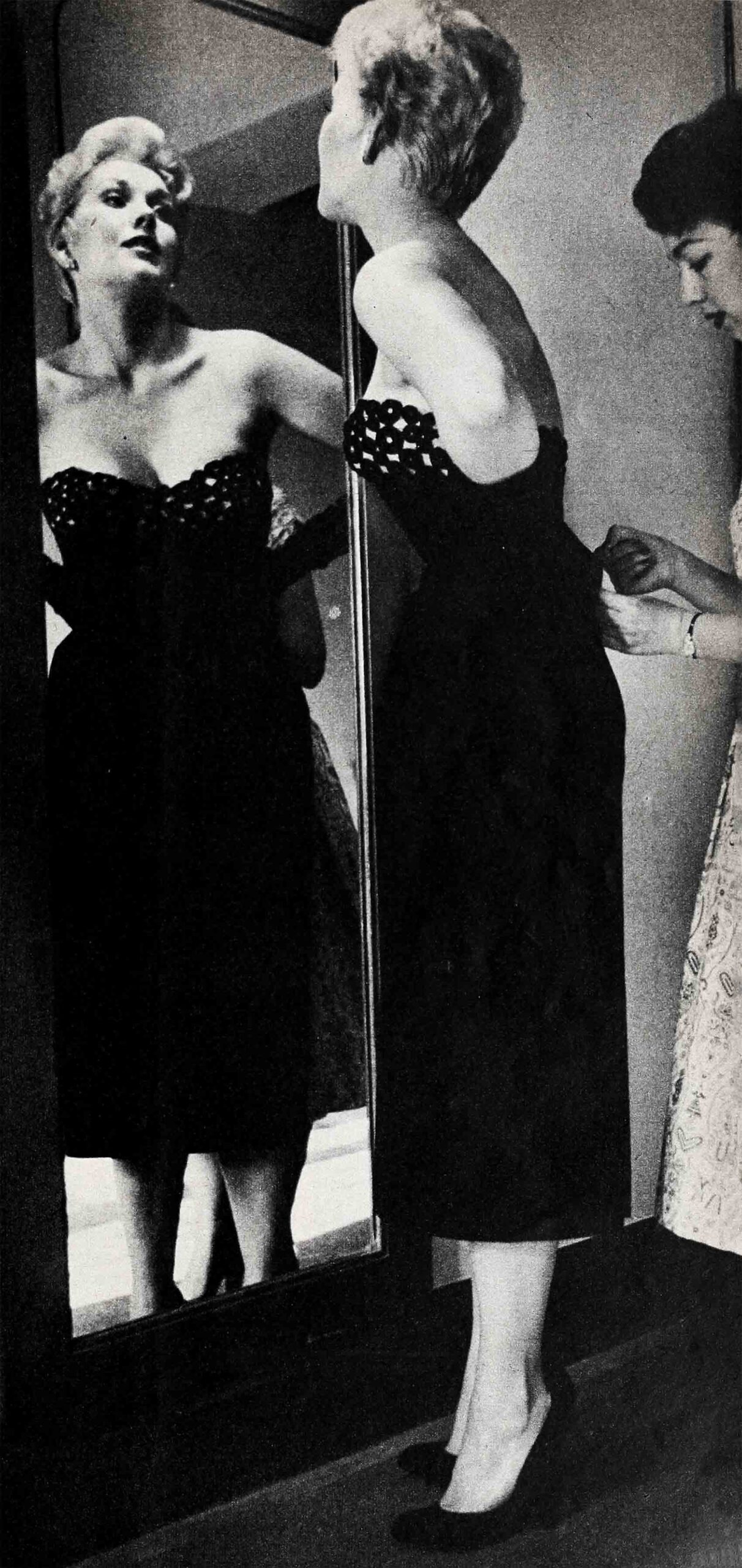

This hardly sounds like the glamorous blond with the sexy voice who caused a minor sensation in “Pushover.” “The statuesque blond with the graceful carriage,” as one column referred to her. Or as a talent expert concluded: “The girl who has everything.” The girl movieland prophets are vowing will be one of the screen’s most popular personalities.

“As I sat there,” Kim says, “I wasn’t Kim Novak, movie star. I was plain Marilyn Novak and all my old fears and inferiority complex hounded me. It’s a shame inferiority complexes can’t be outlawed.”

Kim Novak was born in Chicago—without any complexes as far as she knows. However, it’s lucky that Kim wasn’t born superstitious! She arrived on February 13, 1933 at 3:13 in the morning and her mother had room 313.

The Novaks were unable to agree upon a name for their new daughter, and so they decided that each member of the family could write his or her suggestion on a piece of paper and they’d draw for a name. The slips went into a hat and Kim’s mother had the honor of drawing. The paper she choose was marked Marilyn. And the baby was called Marilyn until Columbia changed her name twenty years later to Kim.

When Kim began to grow, her family was convinced she would never stop. She was thin and always tall for her age. “And gawky,” she now adds. She had braids that reached to her waist and wore clothes that her grandmother made for her. “Plain little outfits, and I so wanted curls and frilly dresses like other little girls.”

“There’s nothing wrong with your appearance,” her mother would tell her. But all Kim had to do was look into the mirror.

“I remember how the boys would make up games and let the girls play, too,” says Kim. “But even when I gathered up enough courage to try entering into things, they’d always tell me to go away. They didn’t seem to want to play with little girls who didn’t have pretty curls.”

Kim’s low throaty voice provided her with another problem. On Tallulah Bankhead, it’s fine. On Kim, today, it’s called sexy. However, for a youngster, it was a heartache. “Once at a football game, I got excited and started to cheer, ‘Yeh, team.’ Everyone turned around and stared at me and started laughing. After that, I sat quietly at the games. I began to hate to have to speak at all.”

Kim’s unhappiness showed in her school work. She couldn’t seem to concentrate on her lessons. She was among the last in her class and usually exiled to the back row. “I began to daydream a lot,” says Kim. “I’d go home and dream that I was beautiful and that everyone liked me, that I was brilliant and was allowed to sit in the front row in the class. But then I’d have to go back to school and there I was—down to earth again. It always hurt twice as much. . . .”

It soon became much simpler to create a make-believe world and walk into it, assured of a welcome. There was a cherry tree in the Novaks’ backyard, which Kim designated as her wishing tree. Whenever anything would go wrong she’d slip out to the tree and sit beside it. Talking things over out loud helped because it was difficult telling even her family her thoughts.

In the hope that she would meet new children her own age, Kim’s parents sent her to camp one summer. But she couldn’t lose her self-consciousness and when school came around, she dreaded it even more. She couldn’t eat. She began to stammer, and every afternoon she’d come running home from school, crying. At parties, which she forced herself to attend, Kim stood against the nearest wall, hugging it. Once in a while she’d get up enough courage to ask a boy to dance, which was the custom, and to accept a dance when asked. But for the most part, Kim was miserable.

She shudders when she remembers her first date. A boy from church asked her to go to the movies with him. She wore a new dress and “a purple coat with a velvet collar. I almost decided there might be some hope for me after all.”

But her complex got in the way again. “Isn’t it a nice night?” inquired Kim’s date after a ten-minute pause in the conversation.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” Kim blurted out. “I had meant to say something witty but the wrong words came out,” she remembers now.

“These were about the only words spoken all evening until we said goodnight.”

During these horrible years, Kim never thought of being an actress. “Other girls did, but I didn’t, although I liked to pretend. I loved to act things out. I was never afraid of being someone else, only when I had to be myself. Our class was required to read books and make oral reports on them. This was the only thing I ever enjoyed. But after the report, when I had to sit down and be me again, I’d climb back into my little shell.”

One day Kim made a report to the class and she acted it out. When she got down on her knees in tears, she could hear sobs from all over the room. When she got to the scary part, there were excited screams from her audience. The following day, Kim found herself in the principal’s office. Her classmates had told their parents about her performance and they had complained.

“I’m afraid you’ll have to write your book reports after this, Marilyn,” the principal insisted. “I didn’t appreciate the fact then, that I seemed to have a quality that could compel an audience to laugh or cry or be frightened,” says Kim. “Instead, I was embarrassed. And so terribly shamed of what I’d unintentionally done. At that point, even my shell had shells.”

Mrs. Novak turned to the “Fair Teen” Club, which, at that time, was called “Calling All Girls.” She talked with the director about her daughter and they decided that membership in the organization might be good for Kim. “All of the kids gathered there,” says Kim. “And there were a lot of activities, among them fashion shows.

“I was given a modeling course and began to take part in the shows. I believe that was when I first began to gain confidence in myself. Off-stage, I was still nervous among people. But on-stage, I was perfectly relaxed. Funny, it was the exact opposite with the rest of the girls.

“Then, in trying to explain to the others how to get over their cases of stage fright, I began to feel more at ease with them. It was an invaluable lesson for me, and I believe it would be for any girl who felt as I did. In helping others, you forget yourself. You have no time to be unhappy or frightened or to wonder what everyone’s thinking about you. You also learn that no one’s perfect, that others, too, have problems. Their problems may not be exactly like your own. They may affect others differently—people react in many different ways. But the important thing is that you’re not alone. You have a world full of company, and it’s good company to have while you’re trying to slay your own dragon complex!

“There’s no fast cure for an inferiority complex. And even when you’re on the right track, you run into obstacles. For instance, suddenly I became popular. Before I knew it, I seemed to have everyone for a friend. ‘But they’re not really my friends,’ I cried to my mother in a moment of doubt. ‘They don’t really like me for me.’ An outsider for so long, I’d become suspicious of my sudden acceptance. So, you see, there was still another dragon to slay. It’s unfortunate, but true, so many times, only when you feel yourself acceptable to others do you become acceptable to yourself. And you don’t want to fool anyone, you want them to know you and like you for what you really are.

“Individuality,” says Kim, “is important, too. It may not seem so in earlier years because you want to be one of the crowd. But the first time I went out with a boy who sincerely said, ‘You’re not like the other girls. You’re different. There’s something special about you,’ well, I was extremely flattered!

“I’ve been told that an inferiority complex is due to a person’s failure to make a successful emotional adjustment,” says Kim today. “The results are varied. Some try to cover their real feelings with brashness. I went the other way, toward seclusiveness. I couldn’t bear the thought of facing my problems—or taking on any new ones—facing anything or anyone for that matter. My family, of course, was wonderful. But other people can help only so much. I had to learn to help myself.

“Now I can understand what happened to me. But how could I, as a child, sit down and analyze my feelings? How could I confide them to someone else when I, myself, wasn’t sure what they were all about? How can any girl? If she falls behind in school or playground competitions, she feels she’s different. If she’s sensitive and someone thoughtlessly teases or rebukes her, she wants to run away and hide.

“She feels she’s incapable of coping with life and she doesn’t know why she should be the one stuck with the feeling, unless it’s because, for some reason, she deserves it. Yet, she is stuck with the complex. In many cases, a girl grows up with it. And then what? Well, I’ll tell you, from my own experience! You either keep running, or you stop and face it!

“Just think of it as I’ve learned to do: Whatever you lack in one way, you can make up for in others. You’d like to be small and cute? But you happen to be tall and slender? Then stand up straight. Be proud. Let everyone know that you’re glad you’re tall. It’s something special.

“You’re not a raving beauty? So what? Every girl can be attractive, and she can do much more than that. She can be charming and sweet. She can be fun to be with. She can be kind and understanding.

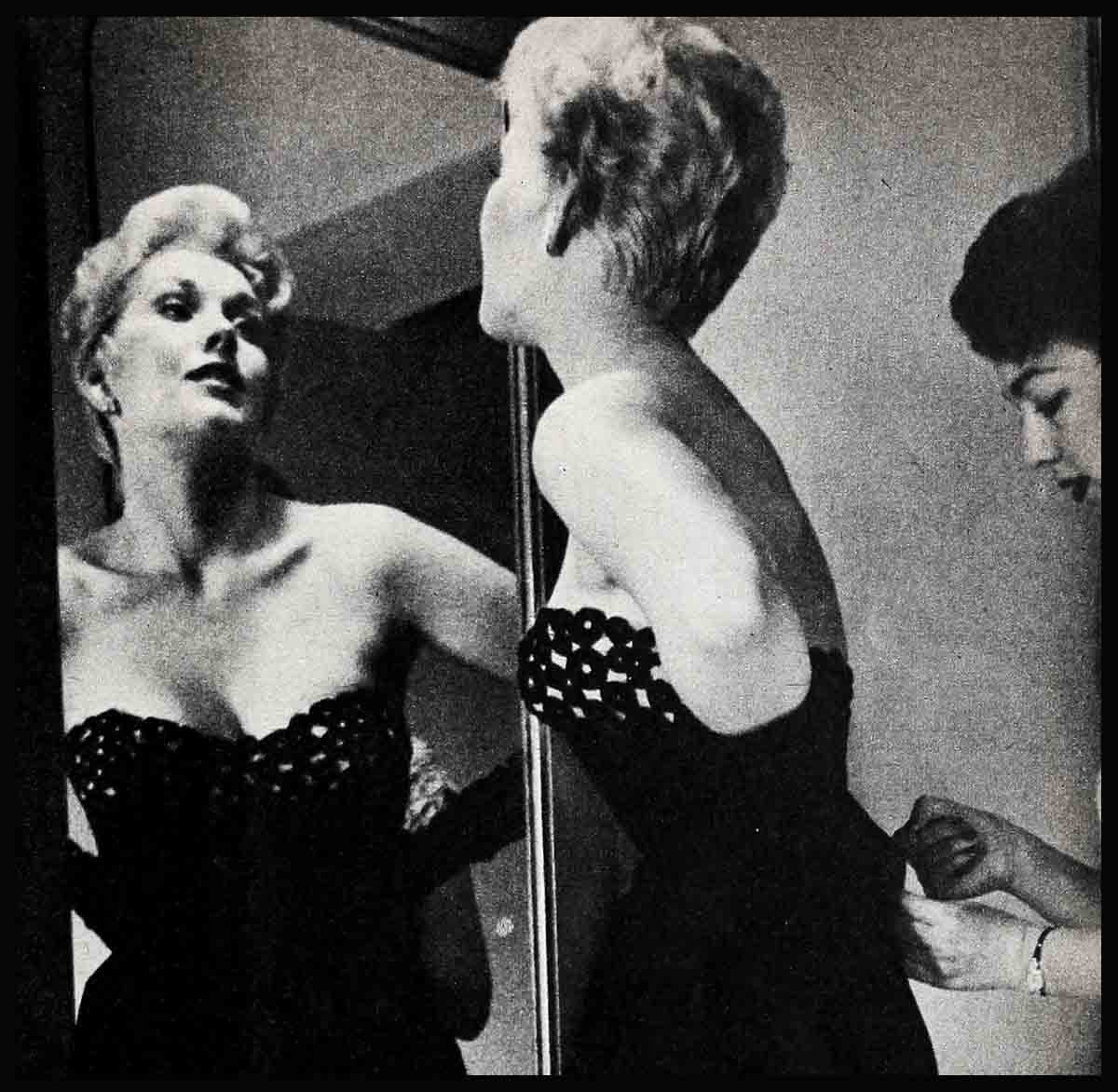

“I’d been afraid to improve myself, afraid that nothing would help, afraid of further rejection and disappointments. I fell into a very human trap: self-pity. If only I’d taken time to look into the mirror, to say, ‘All right, my girl, now let’s see what’s right about you!’

“Children, and so many adults, tend to concentrate on surpassing others, but they can overdo this. They should try to surpass themselves. One of my teachers once said, after giving me a low grade, ‘I’m not comparing you to other students, Marilyn. I’m judging you by the work I know you can do and the work that you are actually doing. It’s simply not your best.’

“If only I’d listened!”

After her days in the “Calling All Girls” club, Kim went into professional modeling. Then she was sent on a tour with three other models. The tour ended in San Francisco and, chaperoned by the mother of one of the other girls, the group stopped in Los Angeles for several weeks.

One afternoon, Kim rented a bicycle and went riding in Beverly Hills. Agent Louis Shurr saw the long-stemmed beauty and asked if she’d ever been an actress. “I was rather curt, I’m afraid,” grins Kim. “My mother had warned me about wolves and about talking to strangers in Hollywood.”

Shurr gave her his card, however, and asked her to drop by his office. She did. Her timing couldn’t have been better. Columbia Pictures’ executive, Max Arnow, happened to stop in while she was there and Shurr introduced them.

Arnow offered Kim a screen test and, several days later, she signed a contract with Columbia. “It will be at least a year before you’ll be ready even for small parts,” Arnow warned her.

But three months later, Kim received a call from Arnow’s office. He had the script of “Pushover.” Would she read it and let him know what she thought of it?

“It’s exciting,” was Kim’s verdict.

She tested for the role and was given the lead opposite Fred MacMurray. “And there I was,” she says. “There were so many people on the set that I was afraid again. And for a while I was so scared I forgot all I learned. But everyone was so kind, people I hardly knew. And I remembered I was there to do my best, to justify the studio’s faith in me. Our job was to make a good picture, and pretty soon I began to forget my fears.”

Kim is doing all right for herself these days. She has, in Hollywood’s book, “arrived.” “Yet,” says one of her co-workers, “there’s still a wonderful quality of humility about her.”

“Could be,” smiled Kim when she heard this. “I know how it feels to be left out of things and I so do appreciate my good luck. And I plan to stay busy, terribly busy. People like me should keep active—not brooding—doing. Accomplishment is the best way to kill an inferiority complex.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955