Voyager—Van Heflin

In a cheap rooming house off the Embarcadero, Seaman Van Heflin was fighting his last battle between the stage and the sea.

Outside the window he could hear the wail of a ferryboat warning its way across San Francisco Bay. The thin shaft of winter sunlight stabbed through the curtain and through the fog that covered his head.

He hadn’t felt this way since that last rough storm, a blow off the Florida coast. It was no day for decisions. But the time had come.

All his life he’d prided himself on aiming for the top. The best grade in math class. The best performance in a class play. But there would be little satisfaction in being the world’s best bum. Two days before he’d paid off the boat from China with two hundred bucks. Now he was broke. Cleaned.

Look at yourself, Heflin. You’re a sad, salty sight. You’ve got to figure this thing out. Why you’ve failed again. What you want. What you are. Or are not. Don’t pull your punches.

Should he risk going back to the stage? Since childhood he’d dreamed of the theater. Dreamed it would be perfect. But when he’d gotten his first look at it in a play called “Mr. Money Penny,” he’d been disillusioned. It was a terrible flop. The stage wasn’t what it seemed. He hated it. He wanted to get away. Fast. So he’d turned to his second love, the sea. He had no illusions about that. He knew it was imperfect. Fascinating in its ever-changing moods. High waves that slapped you down. Then clear, beautiful and serene.

The pull between theater and ocean had always been a tough one for Van since the years he spent with his grandmother in Long Beach, California, when he was going to high school. She was a colorful woman, highly imaginative, with salt in her veins. She lived next door to the head of the Seamen’s Employment Bureau and Van spent his Saturdays over there listening to tall tales.

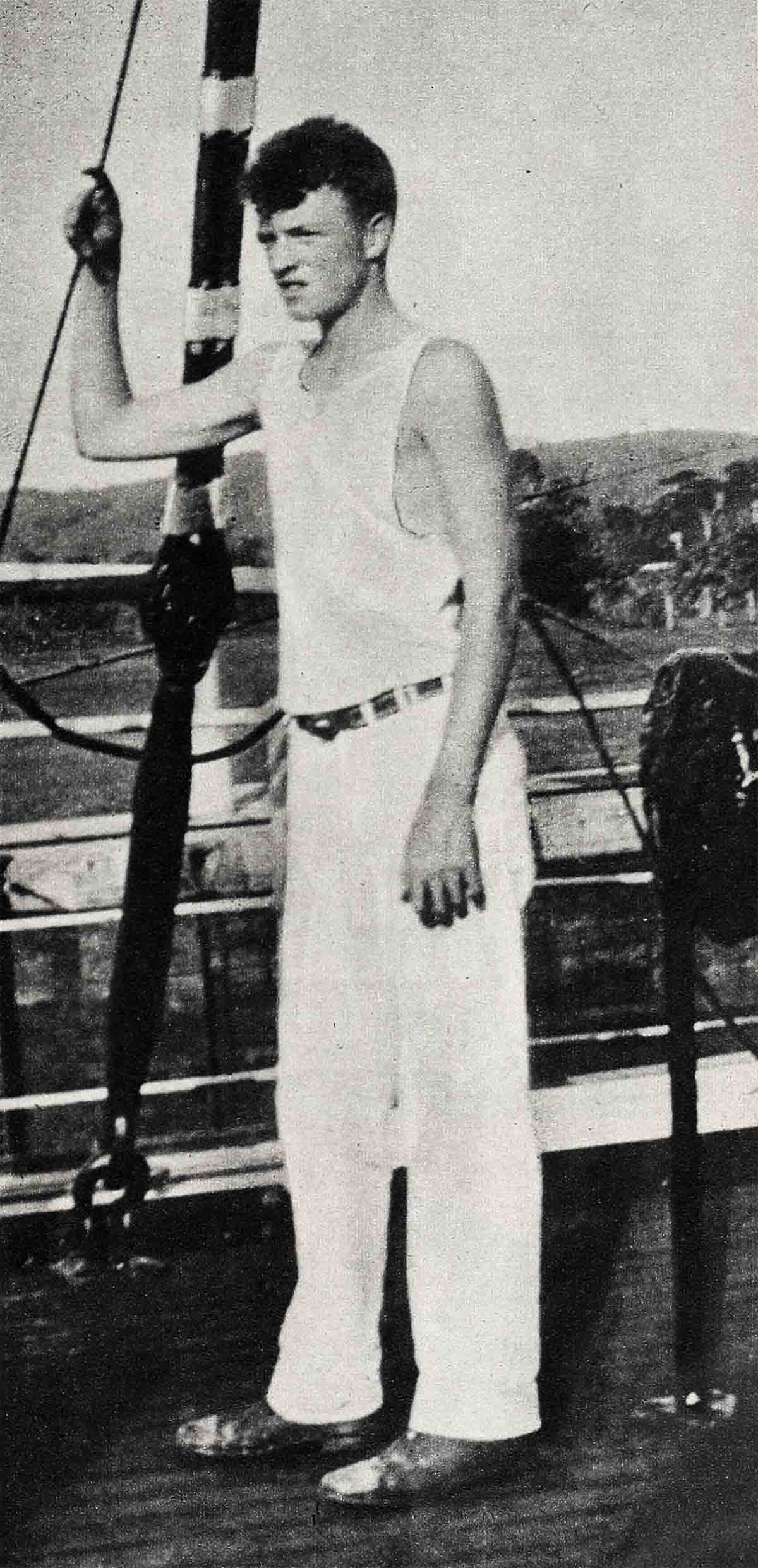

His grandmother, who’d always wanted to travel, was delighted that summer when the fourteen-year-old Heflin signed up to ship out on a fishing schooner for Mexico. From there on, she was always getting her National Geographic down, marking the places where he was going and making him bone up on them. When he came back she’d listen eagerly while he described what he had seen. Van always took his camera along and made snapshots.

He went back to Oklahoma University and studied drama, then shipped out two years later on a cargo boat for the Panama Canal. It was when he landed back in New York that he met Channing Pollock and Richard Boleslavski and got the chance he’d always dreamed of. And failed. And went back to sea.

This then was what he wanted. To visit foreign countries, learn their peoples and languages. He took books along with him to study. A LaSalle Extension course in law. He could be a maritime lawyer. A good one. So wherever the boat would dock Van would spend his time ashore in libraries, studying native periodicals, talking to people, visiting points of interest.

He’d had three years on shipboard and was qualified now for his third mate’s ticket. But he knew it was not for him. He was beginning to drift. He hadn’t cracked a book the last two trips out. And this one to China clinched it. You didn’t have to go to Shanghai to see what he saw. He’d seen the same thing in Chinatown in Frisco the night before. A bar.

He thought of the letter from Boleslavski. The wise director, who knew how talented Heflin was, followed him all along on his voyages with philosophy and advice. “Stay at sea until you can’t help coming back to the stage,” he’d last written. “Then you won’t have illusions. The stage will be bigger than you are and you’ll be glad to be a part of it. Now you want the stage to be part of you. Stay until you’re sure.”

Yes, the time had come. All day long Van walked among the joshing sailors and the familiar maritime atmosphere. By nighttime he knew what he wanted. Second loves were not enough. He would go back with humility determined to make himself measure up to the stage, instead of expecting it to measure down to him.

Once Van arrives at a verdict, whether it concerns his future, a political issue, or a script that doesn’t add up, there’s no compromise. “There can’t be,” he says. “It would be the end of me to myself.” Which rates him as an individualist and in occasional instances the tag of “difficult.”

However, the day was to come when he almost reasoned himself out of Hollywood for keeps. At the time he got the lead on Broadway opposite Katharine Hepburn in “Philadelphia Story,” Van was hurt and disillusioned with the whole picture business and he was sure it would be the stage forevermore. After he had completed a year’s run with the play, doing the role Jimmy Stewart subsequently played in the picture, and had come back briefly for the strong heavy role with Errol Flynn in “Santa Fe Trail,” he still talked and lived the theater. “Let’s face it,” he said then. “For pictures you’ve got to be good looking, which I’m not. Have appeal, which I haven’t. Or be the world’s best actor—which I doubt.”

However, the next year he signed a contract with M-G-M and a friend cornered him for an explanation. “I decided I needed Hollywood when I realized Jimmy Stewart played to more people in a week than I had done in two years,” he said.

He can always analyze the illusions away. He’s idealistic emotionally and realistic in his reasoning, which check and balance makes him the versatile actor he is today. Since his return from the service, where he spent three years in the Field Artillery and later overseas with the Air Corps in the Caribbean, England and France, Van’s covered the whole paint palette. His first role was the rugged, gutsy gambler in “Martha Ivers.” In “Till the Clouds Roll By” he portrays an eccentric self-styled musical genius. In “Possessed” he drives Joan Crawford to murder as the self-sufficient engineer who rebuffs her love. Now he’s enacting the romantic character lead, a mystic philosopher in “Green Dolphin Street” with Lana Turner.

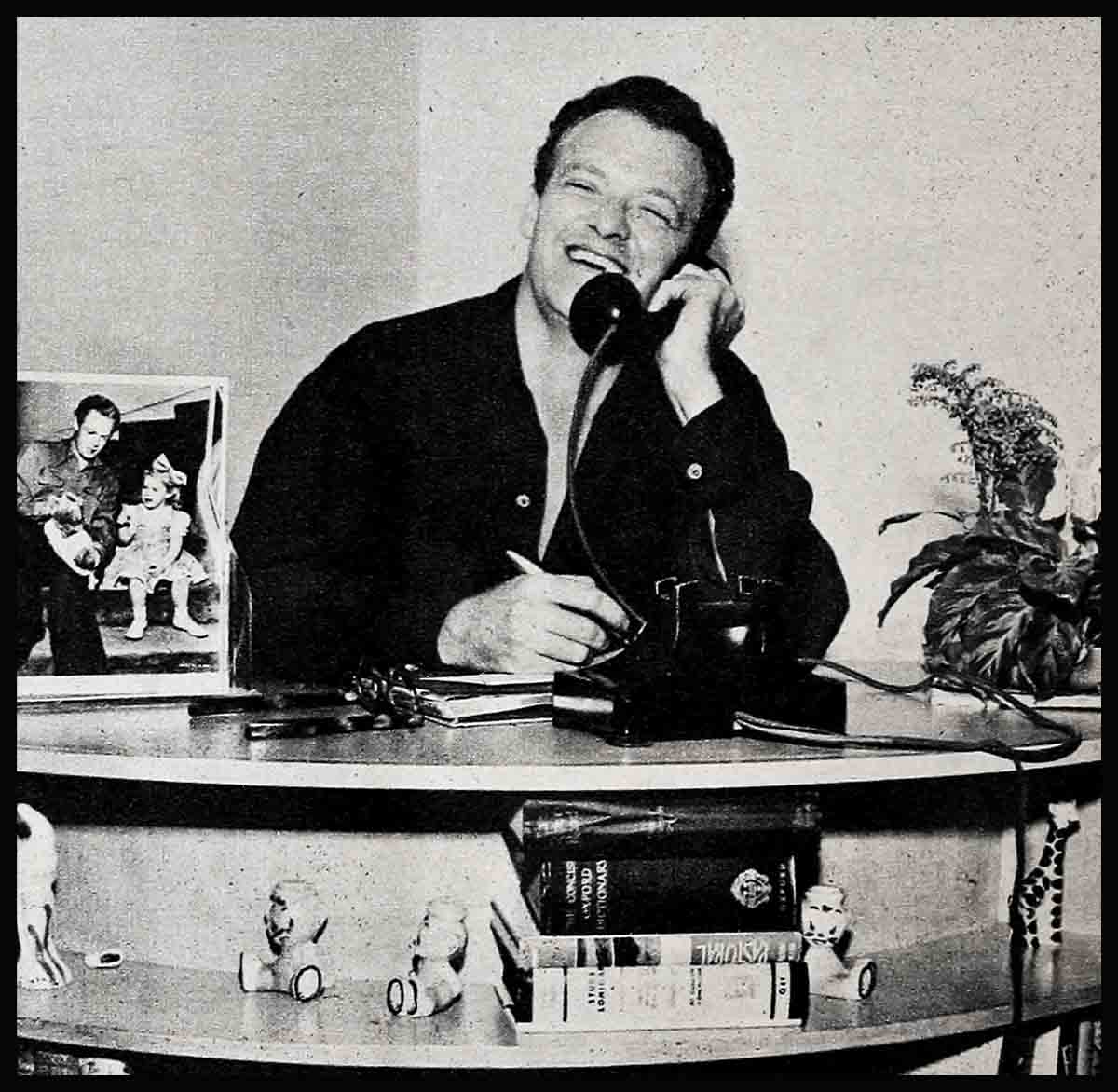

Van constantly underplays off-screen as on. Particularly where it concerns those closest to him. If you really know him, you aren’t fooled by the way he casually refers to his wife Frances as “my funny little redhead,” to three-year-old Vana as “Little Red” and four-months-old Kathy as the “Littlest Red”—in a sort of crimson sequence—when you know full well how much the Heflin harem means to him.

He underplayed his own proposal scene as one could never be underplayed on the screen. Though Frances and Van had met before, they’d never gone together until both were weekend guests of the Joe Pasternaks at their ranch. When they returned to Hollywood, Van didn’t even ask her for her phone number, much less another date. Of course, being Van, he’d already taken care of that little detail with Pasternak. The next evening he called and asked if he might drop by. When he arrived, he suggested that they go for a drive along the beach. “Fine,” Frances agreed. “I’ll get a coat.” As she flung it around her shoulders and started out the door, Van asked her to marry him.

Later, driving to Malibu, she kept reasoning aloud that he shouldn’t marry her yet. “You don’t even know me. You couldn’t be sure about us,” she said.

“Oh yes, I know you much better than you think,” smiled Van. “For fifteen years I’ve known the kind of girl I wanted to marry someday. What she’d look like. How she’d act. She’s you, Red. Yes, I know you very well.” Van had even analyzed himself a dream girl all his own.

He’s a colorful conversationalist, a good storyteller, enjoys philosophizing at great length whether it concerns the future of mankind or the best way to plant cantaloupes. His friend Rex Alcorn, who drops by occasionally to play gin rummy, or so he thinks, says it’s nothing unusual to find himself doing all the pruning. “Van just starts talking and the first thing you know you’re an expert gardener, and you’ve watered two acres of lime trees.”

No one who knows him is ever misled by his casual placid manner, his slow melodic speech. There’s an ever-ready fuse there just waiting for a light. He’s extremely nervous, managing to tie himself in Seaman’s knots inside most of the time. The night before he played his first scene in “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers,” his first film in three years, he couldn’t sleep at all from sheer excitement. He stays too keyed up to eat when he’s working, and tries to relax with a short nap during the lunch hour instead.

He worries as he does everything else—with enthusiasm. He worries about everything and about nothing. About a slight rash that Kathy has that he’s sure will permanently disfigure her. It will take plastic surgery, no less. Even though Frances keeps telling him that lo even by tomorrow it will be gone.

He pays infinite attention to details, and once spent an hour in a Paris book store shopping for a French storybook for Vana, while his GI roommate, Rex Alcorn, a square-shooting Texan and one of Van’s best friends, tried to hurry him along. “She can’t even read English yet,” he pointed out. “What difference does it make which French book you send her?” But Van kept looking through them at the pictures, page by page. “I want her to have the best one,” he insisted.

By nature Van is such an informal kind of person. Earthy. Real. At long last he has the kind of home he’s always wanted. A spacious two-story informal place with a spreading sycamore tree shading the front lawn and two acres of cantaloupes doing some wild broken-field running down the back of the hills in the rear. He has a versatile little garden back there too, comprising a minute com field, squash, tomatoes, and a patch of Oklahoma’s favorite fruit, black-eyed peas.

Luckily the house is so situated that even on a clear day Van can’t see the Pacific. Or Hollywood might find him going out with the tide again. He’s sea-shopping now for a cabin cruiser “—a tame one to take the family out in.” And the salty gleam comes into his eyes when he shows you the old snapshot album.

“That’s the West Cactus, that one the S.S. Santa Maria,” he says enthusiastically pointing out the vessels he’s shipped out on. “That’s Pancho and there’s Murphy,” he says of two crew members in dirty duck pants, cigarettes dangling from their lips.

There are snapshots of wild stretches of open sea. With no beginning and no end. Of a curly towhead with his collar open, his shirttail partly out, gazing over the rail.

Sometimes he still feels the undertow. Perhaps sometimes he regrets walking away from the Golden Gate. But he’s never looked back. You can turn to salt for good that way. And today’s voyage is Hollywood.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1947

No Comments