The Jig’s Up, Maggie McNamara!

One evening last October, a tiny, black-haired, small-framed young girl shyly plunged into the furred and jeweled opening-night crowd inside the lobby of the new Huntington Hartford Theatre and surreptitiously made her way down the aisle to her seat. Slumping into the seat, she immediately buried her head into the program and impatiently scanned the cast credits, seemingly unaware of the glamour and lavishness of the evening and equally unaware of her own importance. The girl was Maggie McNamara, and this marked her first appearance at a Hollywood social event.

It took both Helen Hayes, who was starring that evening in “What Every Woman Knows,” and Elia Kazan to bring Maggie out this night, for on all visits to Hollywood, Maggie McNamara lived in virtual seclusion, shunning newspapermen, photographers and social events.

In fact, for the premiere of her first picture, “The Moon Is Blue,” which made her a motion-picture star overnight, Maggie hid in the projection booth. And she skipped town for the opening of her second picture, “Three Coins in the Fountain.” The studio thought they had her cornered when she promised to attend the gala star-studded premiere of “The Egyptian.” But at the last minute, a relieved Maggie discovered that she had to start shooting on her new picture, “Prince of Players,” the next morning and, instead, spent the evening at home studying her script.

When Maggie did show up at the Huntington Hartford Theatre opening it was partly because she had been asked to by director Elia Kazan, for whom she has great admiration. For Maggie, Kazan represents that wing of her chosen profession whose approval means a good deal more to her than the glitter, glamour and giddy success of being a star.

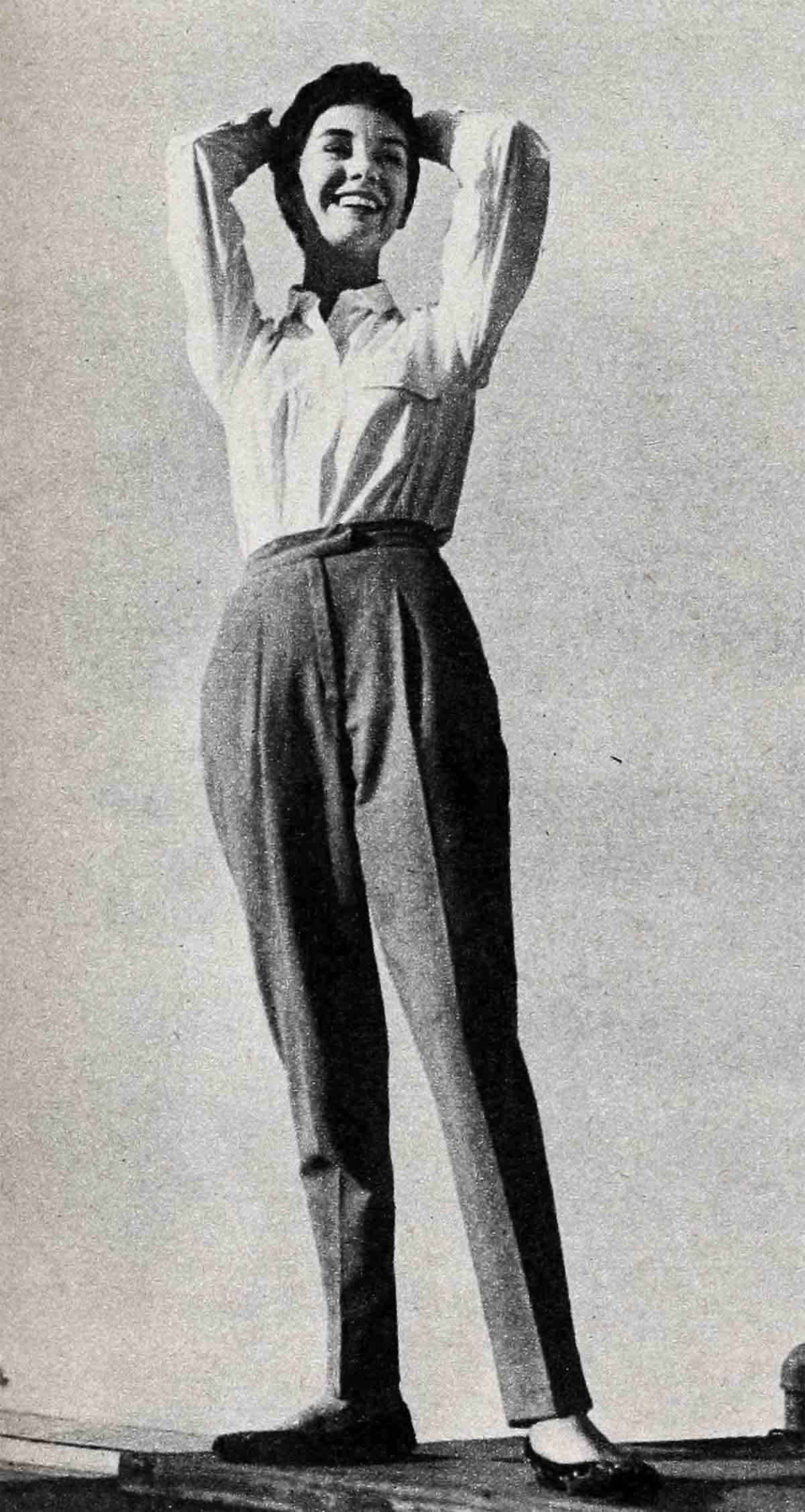

Even so, though, Maggie arrived at the theatre looking more like a fugitive from a math class than a film personality. “I was dressed in old ballet slippers, skirt and a tailored blouse that I’d worn all day,” she admits with a smile that’s not in the least bit sheepish.

The situation appealed to Maggie’s Irish sense of humor, the only trait inherited from her pure Celtic background. For in every other respect, Maggie—a “black Irish” who is moody more often than gay—is as contradictory, unpredictable and non- conforming as can be.

Like Marlon Brando and Monty Clift, Maggie, too, wants to be accepted for what she’s got inside rather than what’s on the surface. The bane of her existence, however, is the word “cute” and it’s the one, unfortunately, most often applied to her pint-sized charm.

Flying back from California after finishing her picture last fall, she was seated next to a large and motherly woman who recognized and insisted on complimenting her profusely. Maggie is that rarity among the human species, an actress who actually enjoys adverse criticism so long as it’s honest and to the point. But this well-meaning lady thought Maggie was just about perfect. Maggie was “darling” and “adorable” and—there was that fighting word again—“cute.” “And what are you going to do back in New York, dear?” she asked.

“Play Santa Claus on Macy’s main floor,” 7 replied tartly and returned to her book.

Fortunately for Miss McNamara, though, she isn’t recognized too frequently. When she had to go to her studio’s New York offices not long ago, she walked twice past the desk of a young lady in charge of publicity who’d tried vainly over the telephone to schedule several interviews with her. She’d never met Maggie in person and didn’t recognize the girl in the simple cloth coat, wearing large horn-rimmed glasses and no make-up. “Who was that?” she asked her boss after Maggie had left. “The new clerk?”

Genuinely publicity-shy, Maggie resents the ballyhoo and actually regrets the very ease with which she’s gone to the top. A friend of hers, a talented young actress who is still struggling for recognition, reports that Maggie was with her one morning when she received a heartbreaking telephone call telling her that a plum role that had been promised to her was going to someone else. Bitterly disappointed, she broke down and wept.

“Don’t cry,” Maggie said. “Don’t cry. If you only knew how much I envy you now.”

“The crazy part is, Maggie really meant it,” her friend recalls. “I can’t dig that Maggie. Here I am, dreaming of one little break that will get me some attention, meanwhile worrying about how I’ll pay my bills each month, and Maggie envies me. She’s got every part she’s ever read for, yet she’s actually sorry that it hasn’t been more of a struggle—that it’s always been so easy.”

The secret behind Maggie’s unconventional reaction to stardom is probably her uncompromising integrity combined with a complete and selfless dedication to her art. Maggie is likely to wince at any such description of herself, finding it insufferably pompous. Yet, by all indications, it is nonetheless true. Hardworking, ambitious, always seeking to improve her art, Maggie is a dedicated actress in the real sense of the word. Acting is a passion with her, as it is with the majority of people in the theatre, and a passion that has only a loose and indirect connection with any expectations of fame and fortune. Unlike most others who succumbed early, however, Maggie didn’t become stage-struck until after she was in her twenties, was actually working on the stage and had already turned down a movie contract. Also unlike most other aspiring actresses, Maggie took a considerable cut in her income in order to accept her first professional part in a Broadway production.

The event that set off the chain reaction leading to Maggie’s eventual movie fame was the appearance of her face on the cover of Life magazine. Maggie, a highly successful photographer’s model at the time, graced the pages of fashion magazines with such regularity that it was virtually impossible to thumb through any of them, from Seventeen to Vogue, without becoming intimately acquainted with her.

“We’ve never had anyone like Maggie before or since,” says Leon Rothenberg, successful manufacturer of junior fashions. “No one could ever ‘sell’ a dress like that kid. Whenever we ran a magazine ad on a dress with Maggie modeling it, we could be sure we had a hit.”

And photographer Jon Abbot, for whom she posed frequently, adds, “There was something ethereal about Maggie. She was shy, sensitive, withdrawn. Yet very sweet, very lovable. She seemed to be forever in a dream. But once you got to know her, you realized she had a brilliant mind. Quite an unusual girl.”

The step from modeling to acting is not as easy or as natural as it would appear. Few top models have ever made the grade in Hollywood, let alone on the stage. But the quality distinguishing Maggie as a model must have transmitted itself on the Life cover effectively enough to arouse the interest of David Selznick, recognized to be one of Hollywood’s shrewdest judges of talent. The day the magazine appeared, he called up from the Hampshire House, asking Maggie to come up he an interview.

Mr. Selznick was impressed. When drama coach Alice B. Young confirmed his opinion he offered Maggie a contract. But Maggie, then only twenty but already characteristically independent, thanked Mr. Selznick politely and turned down the offer.

“I’ve never had enough confidence to do anything I wasn’t thoroughly prepared to do,” Maggie recalls. “I guess I was simply scared, not knowing the first thing about acting. Besides, I had no particular desire to be an actress.”

Financially, it might be added, Selznick’s offer didn’t mean much either. Maggie was then earning around $20,000 a year as a model. But the purely commercial angle, as she was to prove later, didn’t influence Maggie one way or the other. A career as an actress had simply never occurred to her and it took a little time to get used to the idea.

As a child, after seeing a performance of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, she had briefly dreamed of becoming a ballerina. A friend of the family had staked her to lessons and she’d studied with Martha Graham for a while. But she gave up ballet when she couldn’t overcome her self-consciousness. However, she remembered fleeting moments when she experienced the thrill of being able to express herself creatively. Would it be that way with acting? And could she really do it? Six months after her interview with Selznick she made up her mind to find out.

Selznick had stopped producing pictures by that time, and Maggie, typically, didn’t bother to look for a contract elsewhere. Instead she set about learning to act first. She went back to Mrs. Young and enrolled in drama classes on her own.

Mrs. Young, who recalls Maggie as one of the most serious-minded and conscientious students she’s ever had, confirms that Maggie didn’t seem much interested in acting at first. “Maggie had to force herself each time I asked her to act out a scene for me,” she recalls. “Then one day she was ready to go up on the stage and play that scene with other students. I remember how she completely lost herself in it. That was the moment she caught fire. She was wildly excited afterwards and she’s been an actress ever since.”

Though Maggie had natural ability, she had to work hard at developing acting techniques. Her voice, in particular, was thin and high-pitched, and Maggie spent hours on end in her garden at Forest Hills doing speech exercises. She studied with Mrs. Young for close to two and a half years while continuing her career as a model. During that time, she set something of a record by not missing or being late for a single scheduled lesson, although toward the end of her training she frequently had to come in as often as three or four times a day.

The unprecedented result of such unprecedented industry was that Maggie was hired for the lead of a Broadway production on the strength of her performance in a student play which was attended by representatives of the William Morris Agency. Maggie accepted, at a salary less than a fourth of what she got modelling.

The play, an Irish fantasy titled “The King of Friday’s Men,” folded after four performances, but the experience did Maggie no harm. Getting rave notices for herself, she came to the attention of Otto Preminger who, after a reading, hired her for the coveted part of Patty in the Chicago company of “The Moon Is Blue.”

It was at this stage of her life that love—up to then pretty much neglected by the studious, earnest and self-sufficient Miss McNamara—finally caught up with her. David Swift, a young and successful television writer who is one of the originators of the popular “Mr. Peeper’s” show, “Jamie” and the new “Norby” series on TV, saw Maggie at the William Morris Agency. He asked to be introduced and immediately fell head over heels in love with her. He was turned down the first time he asked her for a date; recovered and tried again the next day. They were married eventually after an extended courtship lasting all of nine days.

There was some reason for their haste. Both of them were so busy they almost didn’t have enough time for a wedding, let alone a honeymoon.

David was up to his neck writing a new television series. Maggie was rehearsing during the day for “The Moon Is Blue” and appearing in an Equity Library Theatre performance of “You Can’t Take It With You” at night. They managed to have a brief wedding and a small celebration at the apartment of friends. Next morning at the cruel hour of ten, the bride was back in the theatre rehearsing.

A few days later Maggie and David were on their way to Chicago where they spent the next thirteen months.

Maggie’s success in “The Moon Is Blue” in Chicago was sensational. She topped it off by a two-months run in New York, subbing for Barbara Bel Geddes. Then she went out to Hollywood for the film version of the play, making her movie debut on loan-out from 20th Century-Fox who’d signed her to a contract some time before. Her performance in the movie version of “The Moon Is Blue” won Maggie an Academy Award nomination.

For her second picture, her first with 20th Century-Fox, Maggie was slated for a part in “King of the Khyber Rifles.” Maggie read the script, didn’t like it and gently but firmly put her foot down. To teach her the facts of life, her studio countered with a suspension. Maggie didn’t care and didn’t budge, finally winning her point when her studio cast her in “Three Coins in the Fountain” instead. The picture involved a fabulous trip to Rome, further established Maggie as a star and turned out to be a gold mine for her studio.

Maggie herself isn’t enthusiastic about what she did in “Three Coins in the Fountain” but is happier about her third picture, “Prince of Players,” in which she’s doing scenes from Shakespeare. She’d love to do a full Shakespeare play someday. And she was thrilled with the high critical acclaim that was given her for a recent reading of “Measure for Measure” at New York’s New School for Social Research.

Maggie has so far limited her stays in Hollywood strictly to the requirements of business, rushing back to New York the minute her schedule permits. It’s because she grew up on the upper West Side of Manhattan in an almost exclusively Irish neighborhood and considers herself a dyed-in-the-wool New Yorker. She loves her city most on Sundays and holidays when the streets are deserted and lesser boosters are apt to find it depressing. “It’s so peaceful,” she says. “You feel that the city really belongs to you then.”

Maggie’s attachment to New York is all the more remarkable as her childhood there was far from ideally happy. Marguerite Ann Mary—as she was christened—was the third of four children, three girls and one boy, born to Timothy and Helen (Fleming) McNamara who emigrated to America from Counties Cork and Galway respectively. Under the strain of the depression years, Maggie’s parents split up when she was nine and from then on the four children, older sisters Helen and Cathleen and younger brother Robert, were supported on the mother’s slim earnings as a beautician. Maggie was a timid and solitary child who didn’t (and to this day doesn’t) make friends easily and found her greatest satisfaction in constant and omnivorous reading. She got top marks at the parochial grammar school of St. Catherine of Genoa and later transferred to the Straubenmuller Textile High School where she concentrated on textile design. Beginning to do professional modeling while still in school, she took it up in earnest after her graduation.

Maggie, when she is in New York, lives in an unpretentious three-room apartment on the East Side of Manhattan not far from the United Nations, but facing away from the river and commanding an imposing view of ash cans, skyscrapers, office buildings and apartment houses instead. The furniture is simple, modern and comfortable. On the walls there are some excellent modern paintings and prints. There is a television set and a record player with stacks of records, both popular and classical, but one wall of the living room is entirely covered with book shelves, containing volumes from Aristotle to Zola, and Beaudelaire to Berenson. Maggie, who never was without a book in her hatbox as a model, still reads constantly. “I suppose it’s become a habit,” she says, “and one I’m afraid is not terribly good for me. I no longer feel particularly virtuous about my reading. It’s a form of escape.”

One way in which reading has really not been very good for Maggie is perhaps illustrated by her attitude toward domestic chores. She used to despise and neglect them, automatically curling up with a book instead. (She does her own hair and fingernails, though, skills her mother taught her.) Recently, she’s turned into an enthusiastic cook—for others, that is.

As for herself, Maggie usually has to be prodded into eating and has been known to forget a meal altogether when she’s not reminded. Overweight is definitely not one of her problems. Standing five-feet-two, she weighs only ninety-six pounds and wears a size seven dress that has to be taken in.

Maggie’s trim figure is a gift of nature though, and not the result of exercise. She rarely feels the urge to exercise and, when she does, she’s developed a technique of quickly sitting down and waiting for it to pass away. In California, where she usually stays at the Beverly Hills Hotel, it practically never occurs to her to use the hotel’s beautiful swimming pool. Nor have any other outdoor activities much appeal for her. She smokes moderately and drinks nothing stronger than Sherry, but is happiest in a smoke-filled room with a few intimate friends. She likes talking to one person at a time and detests large parties where that’s usually impossible. A whiz at it, she’ll stay up all night playing charades.

Maggie today is extremely successful. But she still is almost as solitary as she was as a child, seeing few people and counting fewer among them close friends. Generous, loyal, kind, a charming hostess with an exquisite sense of humor and enough brains to talk about any number of topics with wit and grace, Maggie makes a popular hostess and guest, but she prefers to live simply and quietly, hoarding her energy for her work. This dedication to her career, no doubt, can perhaps explain her recent separation from her husband.

In less than four years as a professional actress she’s gone to the top, establishing herself as a star. Beauty and personality have helped her in her career, but Maggie won’t be satisfied unless she wins acclaim for her talent alone. For Maggie is an actress and an artist first and last.

Director Herbert Ratner, whom she’s been studying with during the past two years in New York while between films, sees in Maggie some of the qualities—especially the sensitivity—of the young Laurette Taylor—qualities which made her one of America’s greatest and most beloved stage actresses. He also compares her talent to Marlon Brando’s, stressing similarities in their approach, their originality and their creativeness. “Someday,” Ratner says, “people will forget that Maggie is a beautiful girl. They’ll only see that she’s a great actress.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1955