This I Believe!—Glenn Ford

Several years ago, a magazine published the story of an actor whose soul had been shattered by playing a part in the war-is-hell picture “All Quiet on the Western Front.” The more sophisticated among the readers tended to snicker, and a few even wrote testy letters. But they were wrong. As a consequence of the feeling the role had generated, Lew Ayres, famed screen figure, became an avowed pacifist, stood gamely by his principles in the draft for World War II and finally went to battle without changing his mind. He served well—but unarmed, with a medic unit.

It wasn’t funny—never was. Any working man and actor must in time feel a close identification with his work and begin to absorb in his personal life the coloration of his film material. Often external circumstances bring pressure on him.

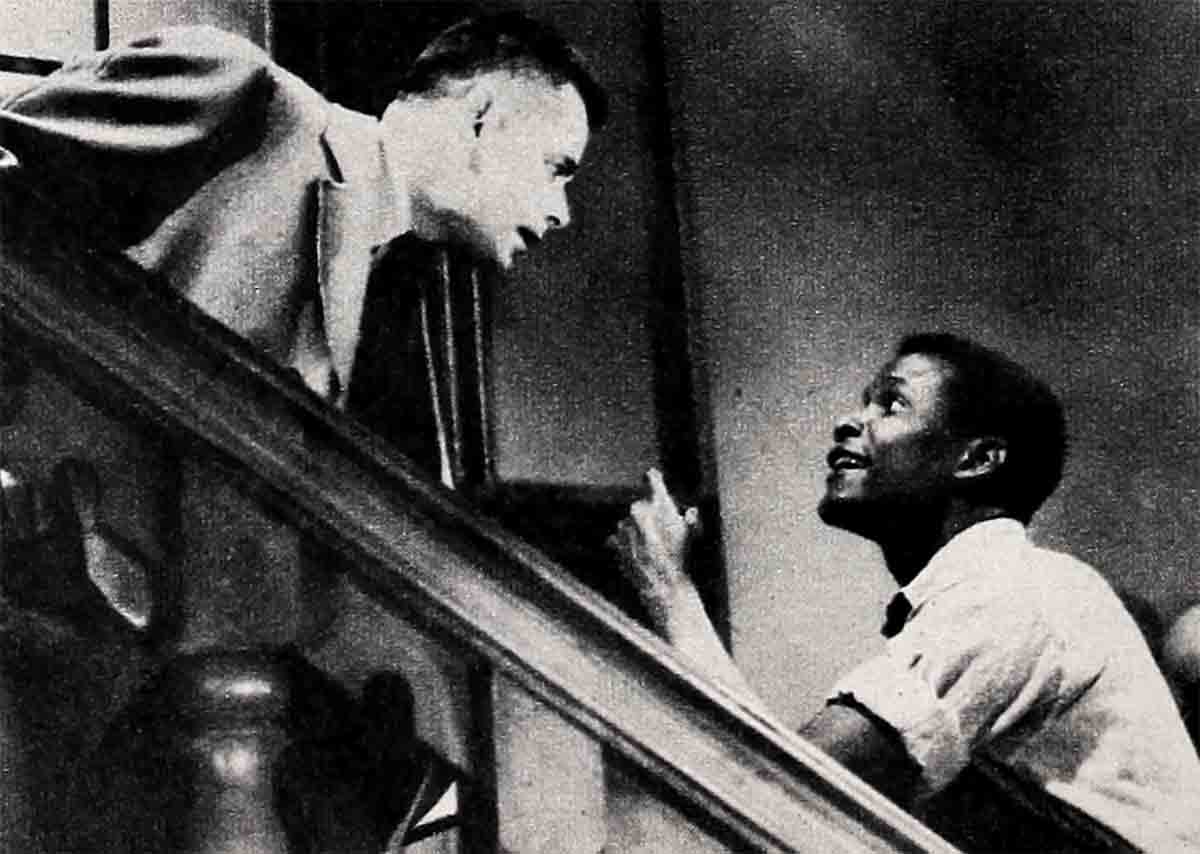

With Glenn Ford, most certainly a sensitive and intelligent person, it has been a case of both. But the external circumstances would not have been necessary. Well before “Blackboard Jungle” had been completed, Ford’s normal concern with the problems of juvenile delinquency had developed. And by the time “Trial” was finished, he was deeply concerned with the problems of racial bias, both actual and in theory. They’re part of his life.

Ford would prefer not to go overboard on this thing.

“An actor’s an actor,” he said recently (he has never quite got over a somewhat apologetic attitude toward being one), “and when one of us sounds off, for instance, on the difficulties of being a teacher simply because he once played a teacher, he’s laying himself open to ridicule. But before and during the filming of ‘The Blackboard Jungle,’ I was being prepped for the part by close contact with actual delinquency—if you want to call it delinquency. And the same thing was part of making ‘Trial, which looks the racial problem right in the eye.

“Then again, I live in Southern California, where you can’t help knowing that a lot of Mexicans are born with two strikes on them. And the way some of them told it to me, when you start out with two strikes, you’re going to get your bat on that third pitch any way you can. They tell me the umpires never call a ball for you when you’re a Mexican in Los Angeles. That’s pretty bitter talk, of course, and it’s not always true. But Mexicans and other minority groups have a better claim to a franchise for bitterness than most of us.”

Glenn Ford is the smooth-running star at M-G-M. “Trial” had been shown to the top brass a few days before, and the top brass had been delighted. Glenn said he had seen the picture but would be the last to know how it was.

Then he became serious. “But there is something I want to say. Not off the record either. You should read some of the mail we got after ‘Blackboard Jungle.’ A lot of it was great, sure. It gave us heart. But you wouldn’t believe the number of people who worked us over for even making the picture.

“You’ve heard the arguments by now, I imagine. That ‘Blackboard Jungle’ was brutal, ugly, exaggerated, shock for shock’s sake, of no use in solving the problem. All I can ask is, how could they say it? How could they say it?

“Of course it wasn’t a pretty picture. Juvenile delinquency isn’t a pretty problem either, and adolescent delinquency is even less pretty. For that matter, adult delinquency’s probably in a class by itself. But you’re never going to find out what you’re dealing with until you uproot that stone and look under it. What’s there? Nothing very elegant. But malignant tumor—is that elegant? A vicious kink in the mind’s not elegant. But you can’t hide from any of these or wish them away or ignore them away. As I get it, the first step in cure is knowing what it is you’re after, looking it right in the face, knowing the best as well as the worst. But certainly the worst. Then you’re over the meanest hurdle.

“ ‘Blackboard Jungle’ wasn’t exaggerated. You can believe me on that. And we weren’t out simply to shock people either. I thought, all of us thought, that compassion lay at the bottom of the picture. But why kid ourselves or anyone else by glossing over the illness? I don’t want to go into sociologists’ territory, they know all this better than I do. And wasn’t it Father Flanagan back there in Boys’ Town who said, ‘There’s no such thing as a bad boy?’ Well, I wouldn’t know about that either. But society’s got to take the rap for a lot of conditions like the one in ‘Blackboard Jungle,’ not the kids. And maybe that’s why so much of society got sore at us.”

It was then that Ford really tock off his 5 gloves and got to work. He spoke earnestly.

“It’s all part of a package,” he said. “This other picture, ‘Trial,’ isn’t too far from it. It’s about a Mexican kid who’s exploited by appeals to race violence. That wouldn’t be so hard, especially here in Los Angeles. I try to think what it must be to be young and poor and Mexican here, but my mind gags. You read the local papers, the kid gangs and the knifings and muggings, and it’s true that the pattern of names is predominantly Mexican. And you get sore for a minute and think to yourself, why? I tried to find out. The kids’ll talk if they don’t think you’re stepping on their toes. Lord knows, their toes are touchy by now. But here’s what it comes to: The chip’s on their shoulder because it’s put there. They might’ve started out with good will. Then one night they find out they can’t seem to get service in a better drive-in or a table in a restaurant where there seem to be plenty of tables. They’re not misbehaving either. There’s only one taboo thing they are doing; they’re being young Mexicans. The first experience frightens them. And the next time disillusions them. And the times after that you’ve got a different person. Now they’re on the offensive.”

Ford shoved his chair back. “I’m overgeneralizing. I admit it. The chances are a few kids are vicious and would be no matter what their environment. And I know that not all restaurant-owners are guilty of discrimination. But the basic situation’s there.

“I don’t know, we pay a lot of lip-service to tolerance, and there’s not a person I’ve met who wouldn’t be sore if you called him a bigot. But let me tell you about some of the mail Elly’s show has got.”

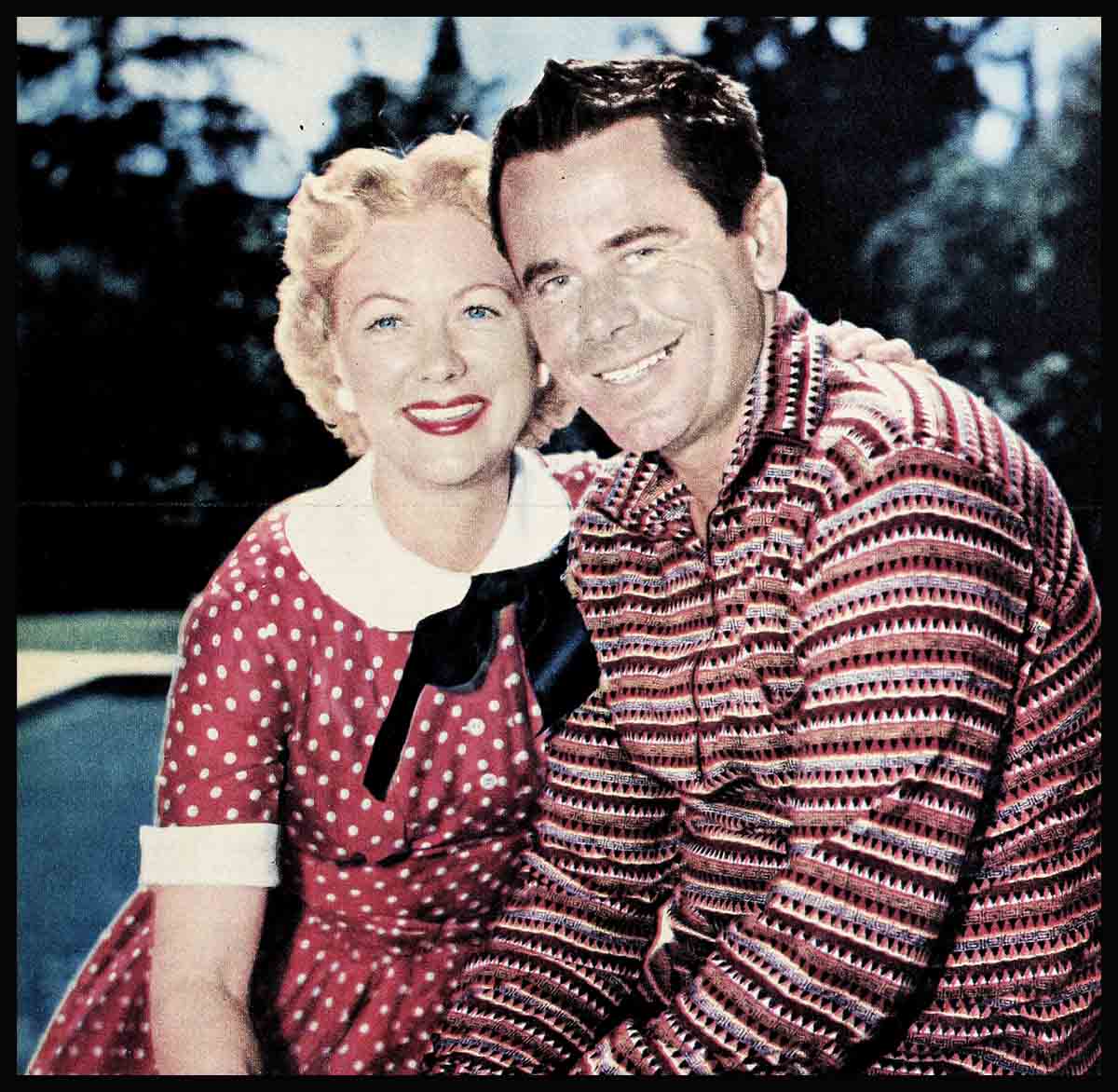

Mrs. Ford, nee Eleanor Powell, has retired from a glittering career in films to be Mrs. Ford, plus the conductor of a charming Los Angeles television show, a kind of Sunday-school class for children.

“One Sunday,” he said, “we had a choir of children—mixed. There were Mexican, Negro, Anglo-Saxon, really very nice. We worked hard on it. Well, some of the mail was stunning, especially to Elly. But some of the mail on that show—not most of it, thank heaven—berated her for mixing the races, for daring to intermingle whites with others. It was hard to believe. These were little children they were talking about, remember—little children, utterly innocent, all one together under God.”

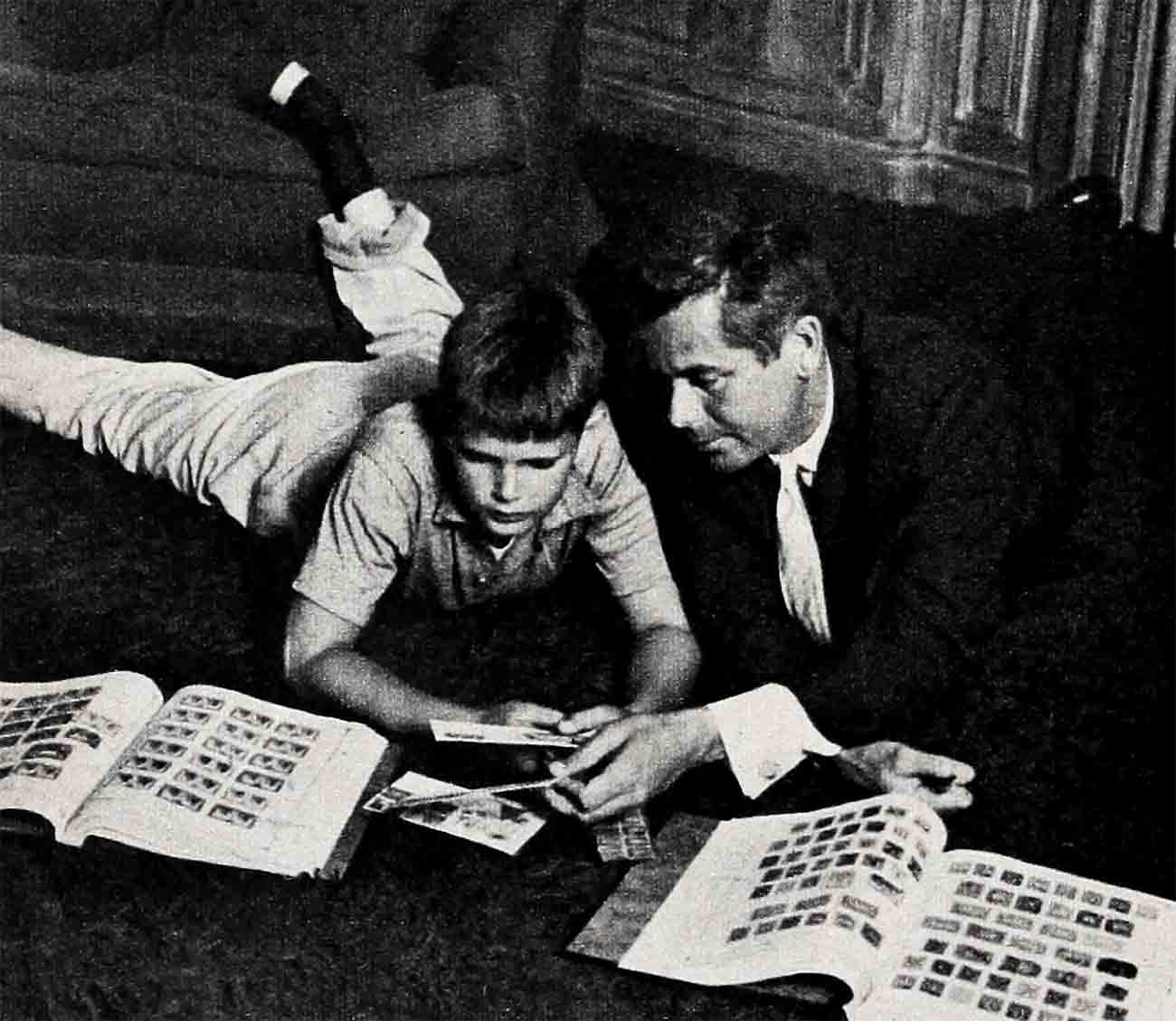

Ford leaned far back, supporting his chair with his hands holding the edge of the table. “My own son, Peter, is eleven,” he said. “There’s no problem of delinquency there—for one thing because he’s pretty young for it, and another, because there’s not a lot of delinquency where we live in Beverly Hills. That’s not to plug my neighborhood, but it fits into the environmental program. The main reason, though, is something else.

“He comes from a very loving home. So he feels secure; anyway, we hope and pray this is so. For instance, there are certain parental rules. So far as an order to Peter is concerned, neither Elly nor I ever countermands the other; we don’t want him confused and therefore insecure. The so-called ‘delinquent’ kids do come from a background where there’s neither love nor security.

“Now Peter’s not an angel or a perfect child. ’’d be worried about him if he were. He came home just the other day with a smashed-up bicycle. That wasn’t bad, but he’d been riding just where I’d asked him not to ride. Well, he knows he has only one bicycle and it’s up to him to fix it or get it fixed—out of his allowance. It isn’t up to Elly or me.”

A Abruptly Ford broke stride. “But my very first reflex of all was what it always is—to tell him the same thing had happened to me. I want him to identify his troubles with mine, and I think the system is working out fine.

“As for what you might call bad trouble, he’s not vulnerable. He works his energy out in other ways; exercise at school or boxing and playing ball with me.”

Ford sighed and dropped the legs of his chair back to the floor. “One night a few weeks ago, though, we had something more serious than a bicycle. A lot more serious. Peter had made friends with some children a few blocks away, and of course they’d asked him to the house. Their parents were home. It seems he overheard the older people talking. After he got back, he didn’t say much for a while, but I could tell he was puzzled. Then he came out with it. A derogatory remark had been made about some people in the neighborhood. And by accident, he’d been exposed to the idea that a neighborhood could be degraded by the residence of a group whose religion, according to what he’d overheard, was somehow contemptible.

“Well, we could straighten it out without making an issue. Peter’s a little young for that sort of issue—yet. Anyway, a child that age wouldn’t be oppressed for long. But there you are. Elly and I don’t know these particular parents and it’s a safe guess we wouldn’t want to. The kids you tend to feel sorry for. But I’d be just as happy if Peter wouldn’t go back to that house again.”

Ford settled his shoulders and smiled thinly. “Maybe it’s trouble, I don’t know. Some of our smartest people out here feel an actor shouldn’t commit himself in public beyond acknowledging it’s a nice day. But you’ve got to live with yourself, too. And a thing like this, if I didn’t stand up to be counted, I’d feel ashamed. Okay. I’m standing against religious and racial bias. Count me.”

Very well, if Glenn Ford wishes to make a stand on elementary human rights rather than hide in a closet and decline to be counted, he has a lot of right to. His three-year hitch with the tough, spartan Marines in World War II was his idea, and he wasn’t just fighting for laughs. It seemed to him there was a reason for fighting the battle and one not too far removed from what he has been saying here.

THE END

—BY JOHN MAYNARD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1955

No Comments