I Wouldn’t Want Him Tamed

I don’t think my husband and I had been in Hollywood more than ten days, when the word began to get around that Rich was a rough-hewn, offbeat character. And it’s easy to figure out how it got started. He loves to talk, and he has a way of saying things that get repeated.

Sitting in the studio commissary one day, after he’d been holding forth at great length, he stopped himself in mid-sentence. Then he said with a straight face. “You know, I talk too much.” No one at the table denied this. And he went on, “My father always said I should have been a politician.”

He paused for just a moment, and without so much as a wink at me, he added, “I think I’d have been good at it. At least the baby-kissing part. Especially girl babies, aged seventeen.”

Knowing Richard. I’m sure he didn’t set out deliberately to confound or astonish anyone. But he wouldn’t do anything to prevent it either, because he takes such an impish delight in being himself.

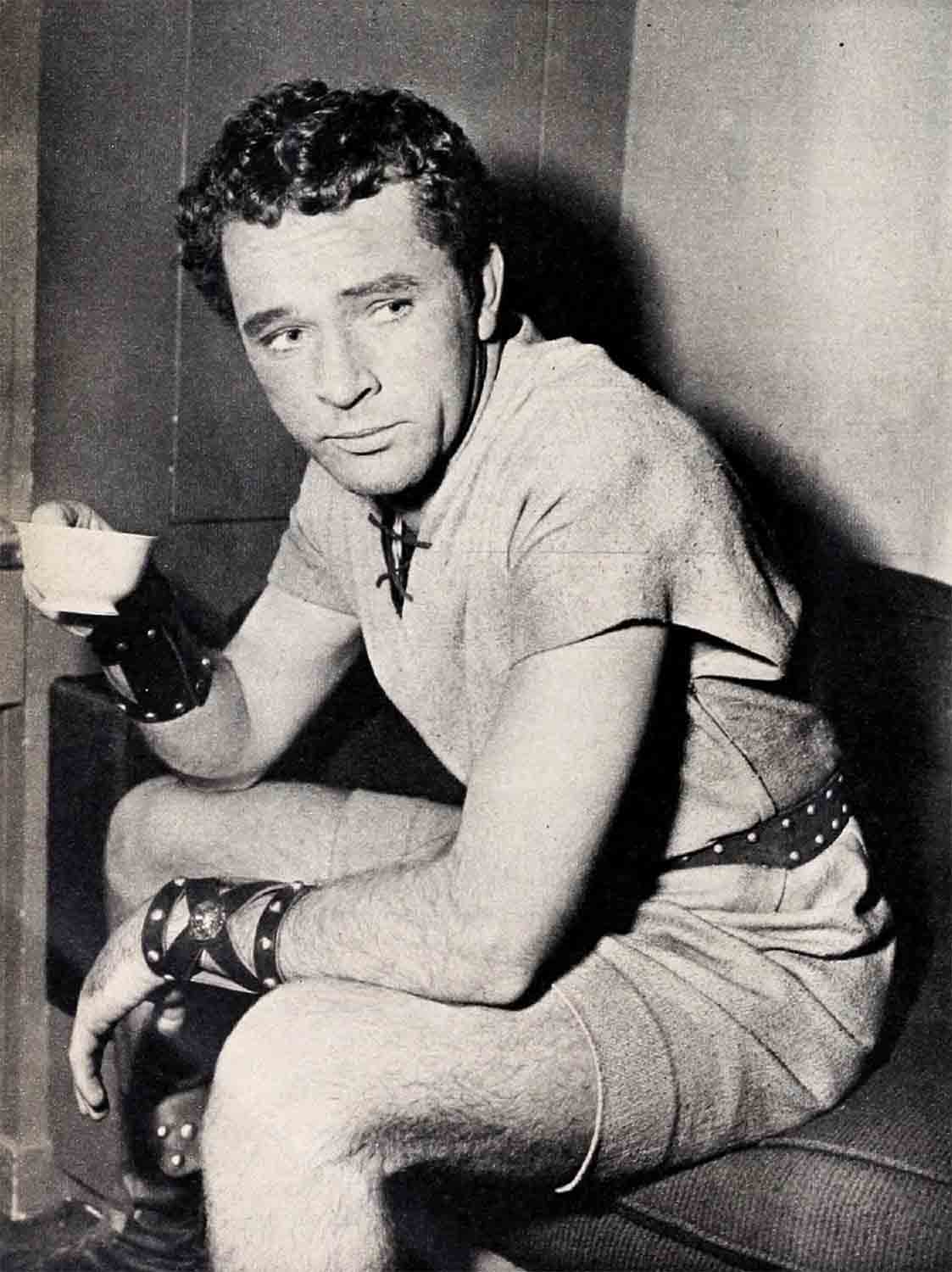

But, in turn, he’s been astonished too. He was truly surprised when his first starring role on this side of the ocean—in “My Cousin Rachel”—made an impression. “I didn’t think I looked good enough or could be a romantic leading man,” he said then. Again he was surprised after tile raves he got for his performance as the noble Marcellus in “The Robe.” He just couldn’t get used to the idea of being accepted as a saintly character. “All my life,” says Rich, “in English movies, or on the stage in London, I’ve played only thugs—real tough characters.”

Many people picture Richard as an unpredictable Huck Finn with a suave Oxford accent. I admit Rich is probably the worst-dressed man in pictures. But my husband, who has been called the poor man’s Laurence Olivier and the British Marlon Brando, is quite unlike other non-conformists. Off-stage, at home or at a party, he has the unreined playfulness of a colt.

Rich delights in shocking stodgy people, yet no one can ever get angry with him. I remember what Emlyn Williams, his good friend and discoverer, once said of him. “Burton,” declared Williams, “shouldn’t be allowed near a columnist. That voice of his constantly bristles with indiscretions.” But even his enemies agree that he is a character, with “charm enough,” a friendly enemy once said, “to set the Mona Lisa giggling.”

When we first came to Hollywood, we had no place of our own, so we moved in with our good friends, the Stewart Grangers. (When Rich moves, he merely borrows a razor and packs a toothbrush.) Since Rich had no car, and had no intention of buying one then, Jean Simmons lent him her racy Jaguar roadster. Occasionally people would ask him what poor Jean was doing while he drove around in her car. “Oh,” he’d chuckle, “she just takes cabs.”

That, of course, is just Richard’s way of expressing the Welsh impishness that bubbles constantly inside him. Yet I have never known a less conceited or a less demanding man. One day, before the actual start of “The Robe,” Rich was doing wardrobe tests when he got something in his eye. Instead of making a fuss, or insisting that he be driven immediately to a doctor, he quietly left the stage, walked a half mile across the lot to the studio hospital, had the eye treated and walked a half mile back again. Another time, during the shooting of the picture, he and I had lunched at the studio. We finished early, so we decided to get a little of the wonderful California sun before Rich went back to the set. We sat down on the curb in front of Rich’s dressing room and basked in the balmy air—I in a summer dress and Rich in rumpled slacks and a T-shirt. A studio executive, aghast at the sight, hinted that this wasn’t quite the thing for a big actor to do.

“Oh, but we always sit on the curb in London,” said Richard. “Why shouldn’t I do it here?”

No, my husband is not exactly the stuffy Britisher type. “When you come from the depths as I have,” Richard has often said, (his father and brothers were all coal miners), “you just can’t get any lower.”

Rich is forever being asked whether he prefers London, New York or Hollywood. His stock answer is, “That’s like asking a man whether he prefers blondes, brunettes or redheads. I can only say I love them all in different ways.”

Our real home is London, where we own a tiny four-flat building. (We live in one flat and rent out the others.) Yet Richard finds Hollywood enchanting. You’ll hear no sneers from him about the town. As Rich says, “Where else but in Hollywood can you chat with Judy Garland, hear Ethel Merman sing, listen while Cole Porter sits down at a piano and plays his own songs, or meet Greta Garbo? There’s nothing like that where I came from.”

I still remember a Hollywood party we once went to where Rich noticed an exquisite, fascinating-looking woman sitting in a corner surrounded by admirers. Rich, who is enchanted by people with interesting faces, simply couldn’t keep his eyes away from her. Finally, he turned to me and whispered, sotto-voice, “Who is that woman, anyway?”

“You fool,” I hissed back, “that’s Greta Garbo.”

I thought, for a moment, Richard would drop through the floor. All his life, Miss Garbo has been one of his idols; she is, literally, one of the few people in the world he would have gone out of his way to meet. And there she was, in the flesh, before him. So do you know what my completely unpredictable husband did? He calmly walked over and pinched Garbo’s knee!

But he was quite charming about it. “You see,” he explained to her, “I simply had to do that! Now I can write my sister in Wales and tell her I pinched the knee of the Great Garbo!”

Garbo actually loved it. A gracious and human woman, she was completely beguiled by Richard’s brashness.

I won’t forget, either, how Richard startled the Humphrey Bogarts on our first visit to their magnificent home. We had met Bogey and Lauren Bacall in London several years ago, when they came back- stage while Richard was appearing at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre. “Katie told us to look you up,” said the Bogarts. “Katie?” echoed Rich, puzzled. “Of course,” said Bogey, “Katie Hepburn.”

“But I don’t know Miss Hepburn,” Rich said honestly.

Despite the comedy of who knew whom, the four of us took to each other instantly, and it was Lauren Bacall who, even then, began boosting Richard to producer-writer Nunnally Johnson, urging him to bring him over from London for the part of Philip Ashley in “My Cousin Rachel.” When we arrived in Hollywood and were invited to the Bogarts’, the first thing the untamable Burton did was to “skate” across the huge marble floor in the Bogarts’ loggia, like a boy sliding on ice.

Actually, Rich adores parties, though he moans and groans at a great rate when he learns we’re going to one. But that, I think, is because he hates to get dressed up. “No matter what I wear,” he says, “I always look like an unmade bed.” Once he arrives at a party, it’s almost impossible to get him to leave. He knows some 600 Welsh songs and can recall at least a thousand others, if pushed; and when his spirits are high, he’ll sing them all.

Though Rich is a marvelous companion and the easiest person in the world to live with, occasionally, like most Welshmen, he becomes distant and withdrawn—but only for an hour or two. When he gets that way, I just leave him completely alone for a while. When I come back, he says, “Sorry I was moody,” and that’s that.

Only rarely have I seen him really livid with anger. And when that happens, it’s almost always because of some lack in himself. In his work Rich is a complete perfectionist; he almost never fluffs a line. But one day, during a scene for “The Robe,” he kept getting words tangled and he got so furious with himself that he literally pounded his head against a wall.

I want my husband to remain just as he is, unchanged, with all his quirks, his verbal indiscretions, his rare moodiness and irresistible impudence. And I no doubt feel that way because he has always held that his most prized possession is his wife. Yet the day we were married, I was all but convinced that Rich would never find a mere wife as fascinating as the game of Rugby, the British version of football.

Both of us were born in South Wales—in Tylerstown, Rhondda Valley, and Richard in the tiny mining village of Pontrhydyfen (pronounced “Pontradeven”). Richard’s real name is Jenkins, and he is the youngest of thirteen children. His father and six brothers were coal miners, but all worked themselves into better jobs in later life. Rich is not ashamed to admit that he and his family lived in the slums.

Fortunately for Richard, a great and wonderful man named Philip Burton, a high-school teacher whose name Rich adopted when he turned professional actor, became interested in the crude, chubby little Jenkins kid. It was Mr. Burton, whom Richard still calls “my second father,” who taught the young miner’s son how to speak English without a Welsh accent, interested him in dramatics, promoted his scholarship to Oxford and even paid for Rich’s clothes during his year at the University.

As Richard says, his stage career began all too easily, because, though he was only sixteen when he won the scholarship, he couldn’t actually enter Oxford, under the school’s rules, until he was a year older. Meanwhile, Emlyn Williams, another Welshman and the famed author of “The Corn Is Green,” was advertising in Welsh newspapers for someone who could speak Welsh and looked twenty-two. Richard could speak Welsh, and, with typical brashness, believed he could look twenty-two. So he read for Williams, landed the role in “The Druid’s Rest,” which ran for seven months at St. Martin’s Theatre in London, and then toured on the road for three months more. After his year at Oxford, Richard enlisted in the Royal Air Force, was sent to Canada to train as a navigator, then landed in New York at war’s end with eighty cents in his pockets. He and a friend, David Evans, sang Welsh songs for their suppers, slept on the steps of a post office and in the subways. But before long, Rich made his way back to London and almost immediate stardom.

Oddly enough, it was through an Emlyn Williams’ picture that Rich and I ultimately met. I had heard that Williams was casting a Welsh film called “The Last Days of Dolwyn,” so I went to him and managed to land a tiny role with no more than two or three lines. As it happened, Rich was playing the juvenile, with a fat, important part. Early in rehearsals, he began teasing me—I was just eighteen—because I had gone to dramatic school. A week later we were going out together, and then after a few weeks more, it was settled that we were to be married.

But actually, we weren’t married until five months later—and this is where that memorable Rugby game comes in. For the record, I doubt that there is in this world so rabid or violent a fan as a Welshman who loves the national game of Rugby.

As it happened, the day we were married—it was February 5, 1949—Wales was playing Scotland for the championship. So fierce was the rivalry that at least 40,000,000 Britons were glued to their radios waiting for the results of that game.

Rich and I were married at 8:45 in the morning, and immediately after the wedding breakfast at a friend’s flat, we separated—I to do a matinee of “Harvey,” in which I was then appearing, while Richard who was rehearsing in “The Lady’s Not for Burning,” stayed on at the flat with one of his brothers to listen to the play-by-play account of that Rugby match. No escorting of the blushing bride to the stage-door by her loving groom!

When I returned to the flat, I found Rich’s brother dissolved in tears and my brand-new husband moaning with grief. Finally, Rich lifted his face from his hands, glared at me and snapped: “Well, woman, what do you want?”

Wales, you see, had lost to Scotland.

On the positive side, this husband of mine has a fantastic memory; he can repeat lines from any play he’s ever done. Yet he can’t recall his phone number, his birth date or the titles of his plays. Or so he says. Recently he confided to a reporter that authoress Daphne du Maurier wanted him to star in the film version of her best seller, “The King’s Funeral.” Reminded that the name of the book is “The King’s General,” Rich said, “Well, I believe the man dies in the end, anyway.”

Under no circumstances will Rich read reviews of his performances. “If they’re bad,” he says, “they upset me, and if they’re good, they’re not good enough.” And he never goes to see his own pictures; he did once, and the sight of himself on the screen gave him the creeps. Rich’s father, now well over eighty, has never seen him in a film, either. “That’s because,” Rich says devilishly, “there are so many pubs, or bars, on the way to the cinema.”

It could be of course, that Richard, as some phrenologist said of the late Bernard Shaw, has a hole where his bump of reverence should be. When some one asked him whether he decided he wanted the eagerly sought for Marcellus role in “The Robe” after he read the novel or after he read the script, Rich replied with a glitter in his eye, “Neither. I wanted it because every actor I knew coveted the part.”

No, I don’t think Hollywood or anything or anyone will ever change Richard, squeeze him into a mold or bottle his bubbling spirts. I know I wouldn’t want him tamed, not ever! He’s wonderful and exciting and enormous fun, just as he is—even if he does love Rugby almost as much as he does his wife!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1954