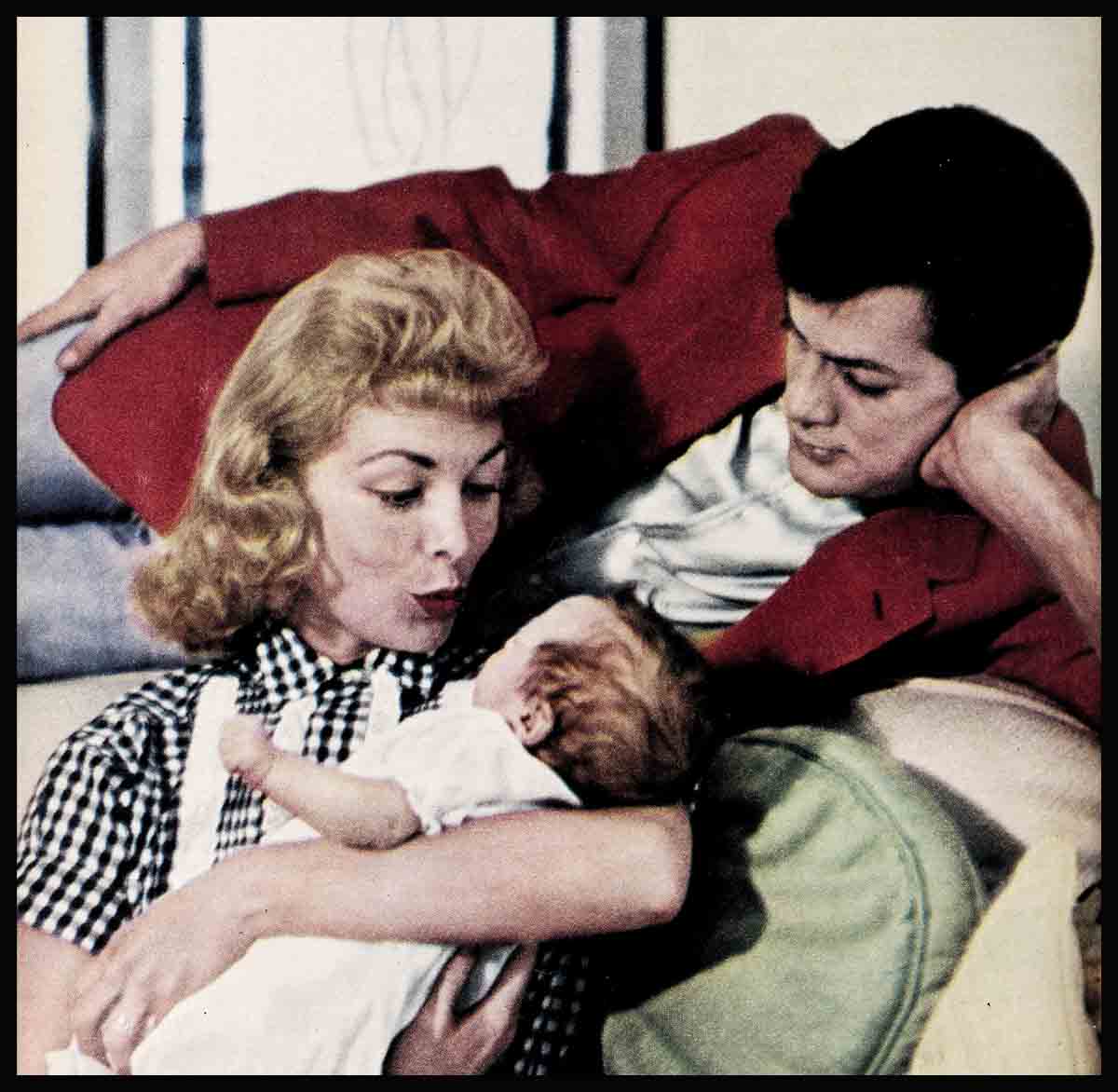

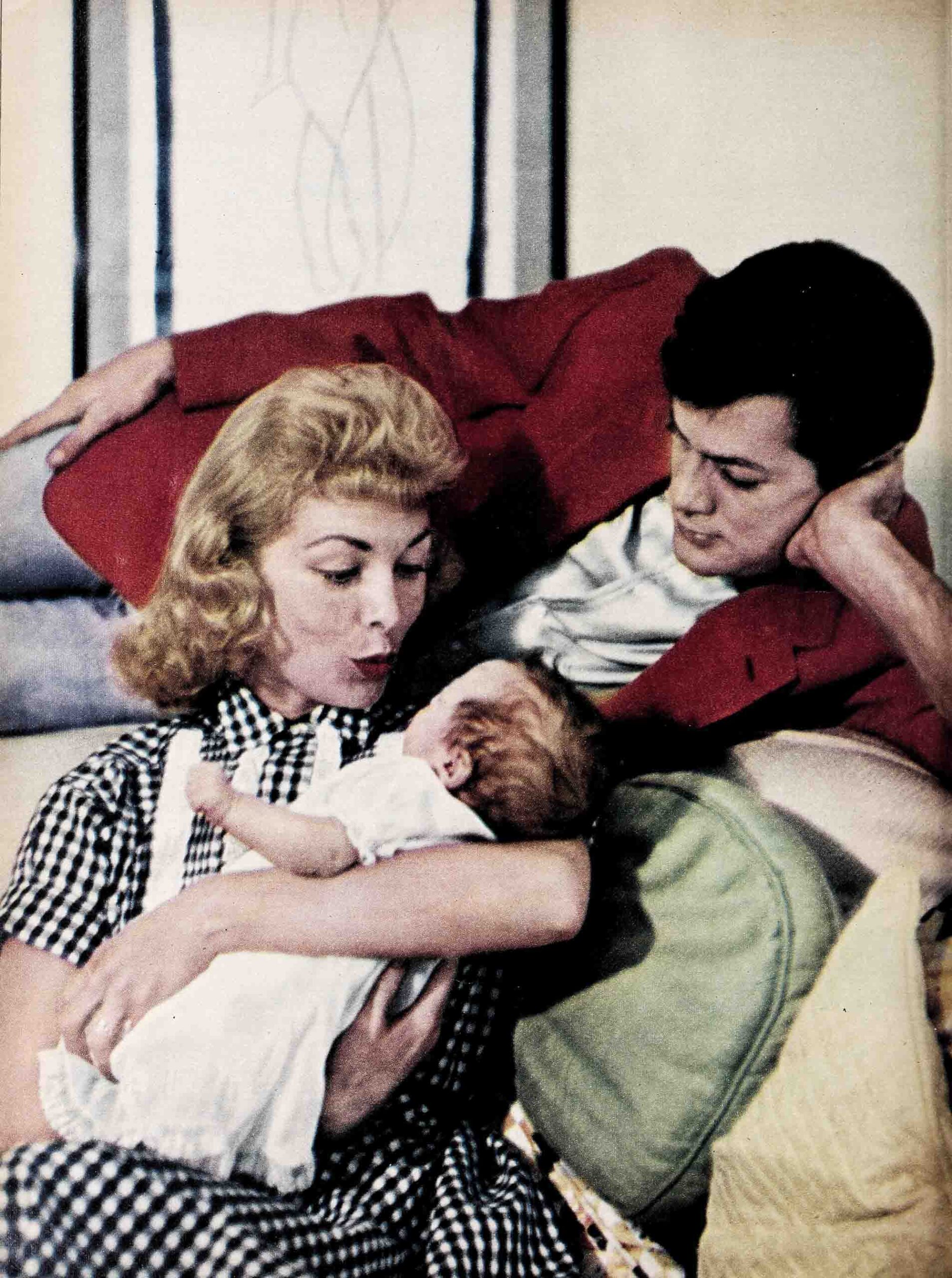

Once Upon A Time . . .—Tony Curtis & Janet Leigh

At two o’clock on a quiet Sunday afternoon late last June, Janet Leigh—wrapped in a white hospital jacket, her wedding ring stripped from her finger—lay beneath the harsh surgical light of a hospital delivery room.

A rubber heel squeaked across the floor. The room seemed full of pent-up breath. The nurses, whispering together, threw strange shadows across the ceiling.

Janet closed her eyes. It’s like waiting for Christmas, she thought. Like waiting nine months for Christmas. Drifting through time, she remembered how, when she was a little girl, the presents were set under the tree one week before Christmas, and how unbearable it was to look at them and have to wait and wait and. . . . Then, with a dull pain rolling up like thunder from the distance and crashing against her, she forgot everything but the present.

At 2:14 P.M., Kelly Lee Curtis was born.

“Janet,” the doctor said, bending over her. “Janet, you have a girl.”

Her first feeling was relief. Her next was a joy which far surpassed any Christmas she had ever known. Then they placed the baby beside her and she felt its warmth and its weight. But before she could reach up a wave of unconsciousness washed over her again.

Outside, in a telephone booth in the waiting room, Tony Curtis waited anxiously for news. They had promised to telephone him from the delivery room the moment his child was born. He waited and waited, but the telephone didn’t ring. Finally, from a corner of his eye, he saw a woman being wheeled down the hall. Impatiently, nervously, he stared up at the telephone. A moment later he realized that the woman must have been Janet.

He ran the length of the corridor and, stopping only for a few quick words with the doctor and a quick glance at the baby, he caught up with Janet.

“Janet!” he whispered hoarsely, excitedly.

“Yes, darling?” She smiled and nodded at him, but afterwards she could not remember what she had said.

“Honey, you’ve got a little girl.”

“Yes, I know, Tony.”

“Do you know what she weighs?”

“No.”

“Six pounds, six ounces.”

“That’s a nice price,” she said happily and went to sleep. . . .

It was a little over a year ago when Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh decided they were ready to have a baby.

They did not say anything to each other for a while. Tony remembered—with every detail still hard and clear in his mind—the night in 1953 when Janet had lost her first baby, and he had been two thousand miles away, helpless, not even able to share the waiting with her.

Janet remembered, too. And she said, “It was nature’s way of saying that some- thing was wrong. And . perhaps we weren’t quite ready to have a baby then.”

“And now?” Tony asked. She nodded.

“We decided we were ready to have a baby,” Janet says today. “We decided we were mature enough to be responsible for another human being and to share ourselves and our marriage with another person. We knew that a baby would change our marriage, but we weren’t quite sure if a baby would make our marriage stronger. That was something we had to wait nine months to find out.”

“We found out,” Tony says.

“Yes,” Janet echoes. “We found out.”

“In the years we’ve been married,” says Tony, “we’ve had our share of problems. We’ve shouted at each other and slammed doors and occasionally done worse. But I don’t think you can show me a man who’s been married even two years who hasn’t been angry at his wife at least once. I don’t think you can show me a woman who’s been married two years who hasn’t cried because of her husband at least once.

“But we’ve really only had one basic problem. For better or for worse, we’re two strong people. We each wanted our own way and we found it difficult to compromise. If we had an argument, the important thing was who was going to win and who was going to lose. Usually both of us were too stubborn to give in.”

“And too proud,” Janet adds. “Now, since the baby, we have an easiness, a closeness that we never had before.”

“It’s strange,” Tony says, “but we’re more considerate of each other without really trying to be.”

“Suddenly,” Janet adds, “it’s not just my pride and my wishes fighting Tony’s pride and Tony’s wishes. It’s both of us thinking about someone else.”

“And it’s not a question of whether Janet is going to win or I’m going to win. It’s as if we have discovered an unwritten law that tells us when to compromise, when to give way.”

Every day that Tony and Janet are sharing now is filled with new sensations. Even their comfortable, yellowstone house seems strange to both of them. Like people lightheaded with too little sleep, they are almost painfully sensitive to sights—a half-empty bottle tilted awkwardly against a railing; and smells—the sweet-sour smell of a baby’s room, the oily fragrance of baby lotion. They are conscious of sounds—the nurse’s footsteps on the stairs, water boiling on the stove, or the wind whining faintly through the chimney like a baby moaning in a troubled dream.

It is Tony’s foot that is first to the stairs then. It is Tony’s heart that beats louder until he realizes that it is only the wind. Then he turns, half-sheepishly, and goes back to his chair. He is only now beginning to accept his daughter as a person. For Janet, this realization came earlier and easier.

“It was the morning after Kelly was born,” Janet says. “I looked at this lovely thing that I held, with its arms moving and its feet kicking, and suddenly I understood that this was a human being. And I was amazed to think that I had carried her inside my body for so long. When you are pregnant, you think ‘baby,’ and you talk ‘baby,’ but you don’t really know what the word means.”

For Tony, it was different. “After I left Janet in her room, I went to the nursery and looked at the baby. I looked for a long time, but she seemed no different from any of the other babies in the hospital nursery. There was no mystic way in which I could have identified her. The only thing I could do was read the name on the crib and hope that they hadn’t put the wrong baby there. I could feel no emotion toward this one particular baby. I think that you get attached to a baby slowly. When it lives with you and begins to recognize you and smiles for the first time. Before that there is just the new sensation of being a father.”

To Tony, that sensation was a mixture of many intangible things. He was overcome—quite literally overcome as though he had been knocked down by a strong wind—by a mixed feeling of joy and triumph and the dismaying realization that he was about to cry and, above all, “the feeling that we had discovered something for the first time, that we had done some- thing that nobody else could do.”

Kelly Curtis is five months old now, and the exquisite wonder of that sensation has faded. Kelly is still too young to crawl or talk, but she has already caused changes in her parents that are out of proportion to her weight and size.

“I feel more mature,” Janet says. “I have to be. When there was only myself to worry about, I could go on making the same mistakes forever. When I look at Kelly now, I know that each thing I do is irrevocably important.”

And Tony says appraisingly of his wife, “Janet has more assurance now. She still can get upset and nervous over trifles, but she’s more tolerant and more patient. There’s something in her eyes, too, and a new way she carries herself that I can’t describe. But, somehow, she’s more beautiful now than she has ever been.”

Janet, who has always hated the disorder of having even one ashtray out of place, has been in the throes of having the house remodeled. The bathrooms are unusable and full of coiled lengths of wire. Pipes and conduits are sprawled across the stairs, and electricians are stamping over the roof and crawling through the second-story windows. Janet cannot shut her eyes to all of this, but she finds the disturbance less important than it used to be. Even at the worst times. . . .

“Mrs. Curtis,” one of the electricians said tentatively the other day, “have the plumbers gone?”

“Yes,” she said thankfully.

“I think you’d better call them back, ma’am. There seems to be water leaking in the bathrooms.”

A year ago, Janet would have been nearly hysterical. This time she was only annoyed. And she was able to go into Kelly’s room a few minutes later and leave the strain and tension that she felt behind her, dropping it at the door.

“If I have changed,” says Janet, “Tony has changed, too. He’s more willing to accept responsibility now. He used to want to hide from responsibility if he could. But when we knew I was pregnant we had to sit down and plan. We had to talk things out and think them out. Whether we should buy a house; how much money we had; how we should budget for the time when I wasn’t going to work. And Tony wanted to accept the responsibilities.”

Tony doesn’t think that he has changed. Or, rather, “I’ve changed,” he says, “but not because of the baby. Having a baby changes every woman. Her emotions change, and so does her body. But to a man, having a baby is really external. He can’t nurture it. He can only stand on the sidelines and watch and be a little awed. If I were still a child, as I was two years ago, being a father wouldn’t have made me grow up.”

But they both agree that their life has changed. “It isn’t any fuller,” Tony says. “It was always full. But now it’s richer.”

“Richer,” says Janet, “but not in any way that you can describe easily. I’m not sure I understand it quite myself, but it’s like this. The baby makes me laugh, but it’s a different type of laughter than I’ve ever known before. It’s just such a true joy that the laugh seems to bubble over, to come out in spite of myself.”

“Richer . . .” Tony echoes. “When Kelly was a month old, I went to pick out a new car. And somehow this new car is more pleasurable to me than any car I’ve ever owned. And I know that it’s because the baby is going to ride in it. I bought a new suit, and the same thing happened. The new suit was better than any other suit because, when I wear it, I will be holding the baby. I guess it is that having a baby has made other things taste and seem good.”

Tony is quick to add that he and Janet are guilty of reading things into the baby that aren’t there yet. “She’s still half-vegetable. She recognizes us, smiles at us and coos a bit, but that’s about all. Most of the time she eats and sleeps and eats again and sleeps some more and gets her diapers changed. And,” he adds, “she cheated me out of something.

“Ever since I learned that Janet was pregnant, I waited for the day that I could speed toward the hospital, flag down a policeman on the way, shout, ‘Follow me. My wife’s having a baby,’ and weave through streams of traffic with the sirens screaming behind me. But Kelly decided to give Janet labor pains at 7 A.M. on a Sunday morning. Everybody else in Los Angeles was sleeping. There was no traffic to weave through. There was no policeman. And I didn’t even get a chance to run through the red lights. Every time I came to a signal, it turned green!”

But then he smiles at Janet and he doesn’t sound as though he minds being cheated. He doesn’t sound as though he minds anything. Because all is so right and so wonderful now, for two of the most adoring parents—and the happiest lovers—to be found anywhere.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956