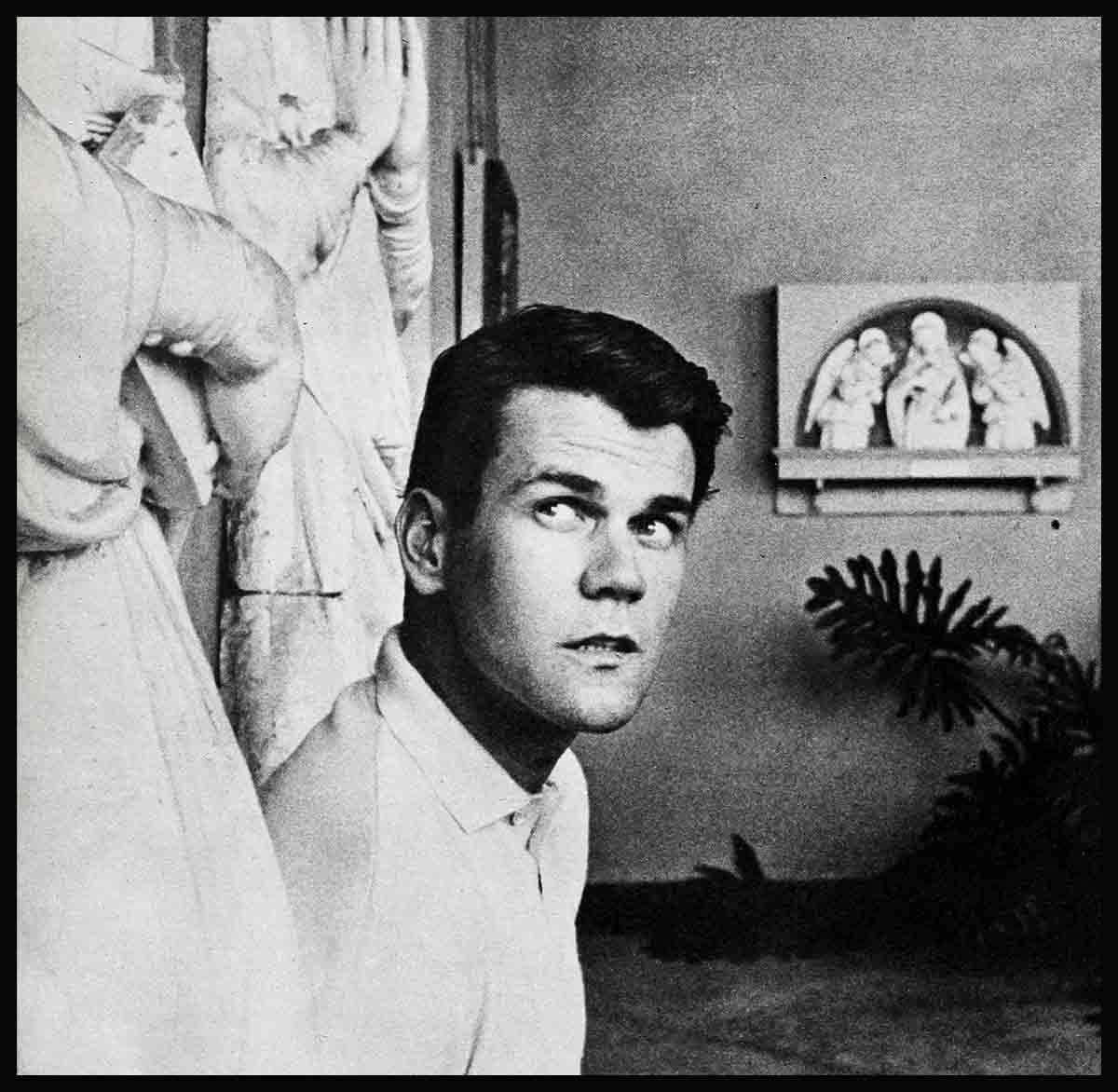

I Worked . . . And God Rewarded Me—Don Murray

On the rough bunk in the tiny room, scarcely bigger than a large closet, Don Murray lay staring at the cracks in the ceiling, watching as the pale light of the cold winter dawn revealed them in all their sharp ugliness.

Another day. The day before Christmas. Christmas Eve. He pulled himself up and sat on the edge of the bed heavily. He tried to get up, but he could not. A wave of dizziness struck him, and he held his head in his hands until it passed. At last, he rose and tried to pull on his clothes as quickly as he could, to guard against the blasts of icy air that the flimsy, broken walls could not keep out. But it was slow going. He had lost thirty pounds. His skin was still yellow from an attack of hepatitis that almost cost his life. When he bent to pick up his shirt, there was a dull ache in his side—the result of an appendectomy, performed with scanty anesthesia. Dust that seeped into the room and covered everything made him cough. He was suffering from lung congestion, following a siege of pneumonia.

He staggered out of the room like a man bent under a heavy burden. But in his heart, Don Murray carried a burden much heavier than that of physical ills. A burden of doubt.

“Could it be that I was wrong, after all?” he thought dully. “Wrong to come here, wrong to do what I am doing?”

As he walked down the shabby, dirty street in the heart of the worst Naples slum, he could feel the hostility and hopelessness that surrounded him like an impenetrable wall. It was in the surly glances of the men, the vacant, empty faces of the women, the open jeers of the children.

If Don Murray had firm convictions that war was an evil before, he had terrible affirmation of those convictions now. Here, he saw that war killed with more than bombs and bullets. It had devastated these people’s souls. Stricken with sickness and poverty, the older people had no hope—only hate. For the young, only one avenue of escape was open. Crime. Stealing and violence had become an accepted way of life—because they appeared to be the only way to survival.

To Don Murray, who had answered a call of the Congregational Church to come here to do relief work among these people, particularly the most hopeless of all, 1200 refugees in a displaced persons’ camp near Capua, this came as a revelation—and a shock.

He had thought that his trials were over. And indeed, his faith had been sorely tried, since the day in 1948 when, called to register for the draft, his conscience would let him do nothing else but list himself as a conscientious objector. For Don, this was not easy. His career, his reputation, his whole future was in jeopardy. At that time, he was not a member of any of the three great historic peace churches—the Society of Friends (commonly called Quakers), the Mennonites, and the Church of the Brethren. He went to the Congregational Church, of which his mother was a devout member—and from childhood, he had also attended Catholic services with his father, noted stage manager Denny Murray. He had an older brother, Bill, who was a Marine. And he was an actor.

So for Don there followed two years of grilling, investigation by the FBI, and nerve-wracking waiting. When at last he was called for the final trial, his mother came, and in a firm, clear voice declared, “I have one son who is a Marine, and another who is a conscientious objector. I am proud of both.” Then, he could scarcely believe his ears. The authorities told him that they had found him to be a person of unquestioned character and sincerity, and would classify him as a conscientious objector. (“I know now,” says Don, “that for a long time they just couldn’t believe that an actor could be sincere. But I learned one big thing from that experience—if you don’t desert the truth, it won’t desert you.”)

Don was not afraid of danger. The Korean War was on, and he was eager to go over there for the term that conscientious objectors serve in lieu of a military stretch. He applied to the American Red Cross and other field organizations, and was bitterly disappointed when mons of them could find a place to use him.

At last, he found acceptance with the Church of the Brethren. Although numbering only 180.000 members in this country, this church, like the other peace churches, conducts a vast foreign relief program, supported by voluntary workers who receive only a pittance for living expenses, and generous contributions from members that, during the last war, ran well into the millions.

When Don left for the training camp in New Windsor, Maryland, he expected to find “little men with beards.” Instead, he found a peace and a joy he had never known, with a stalwart, dedicated people who were filled with the optimism and enthusiasm that comes only to those who have found a real purpose in living.

Now Don shared that purpose, too, and when he was assigned to a relief project in Kassel, Germany, he put it to work with a vengeance. A powerfully-built athlete who had won many a track award, he was given a job as stonemason and bricklayer in building a new relief center. It was a far cry from the Broadway stardom that, as a result of his acting in “The Rose Tattoo,” had been just within his grasp. But in it, he found a satisfaction he had never known before. At night, he studied German. He organized sports activities with the German boys, and, when his German improved, gave talks about the true meaning of democracy in the schools, finding there a purpose of real service to his country. It made him pleased and proud, too, to discover that the U.S. Army gave the relief activities hearty support, often lending needed equipment.

Then the call came to go to Naples. The need, he could see, was great, and it was a challenge he could not refuse.

And there, he faced what seemed like certain defeat. They opened a little clinic—but no one came to be cured. “What do these people want from us? How are they trying to use us?” was the coldly suspicious attitude of the people, wary from past mistreatment.

A ray of hope came when, out of desperation, a sick child was brought to the clinic, and made well. Then, others came, and soon the clinic was filled to overflowing.

In the refugee camp, too, there was much that could be done. Don, who set about mastering Italian as quickly as he had mastered German, tried to keep the youngsters out of trouble with organized activities, and give the older folks a purpose and a little money by staging bazaars where they could sell their handiwork. But to restore life to these dead spirits seemed impossible. How could one restore hope in the future . . . when there was none? All Don could do was to work harder. And his health broke.

On that Christmas Eve in 1954, his term of service was almost ended. And he felt that he had failed. When he got up before the people in the refugee camp to introduce the little Nativity pageant that he had prepared, his heart sank. The camp authorities had warned him of what would happen, and they were right. From the motley assemblage of all creeds and nationalities, a chorus of jeers and boos drowned out his first words, stones clattered on the stage. But Don went on. “We can all share respect for Jesus Christ,” he said, “if not as divine, then as a man.”

Then, as the age-old story unfolded, a curious hush fell upon the crowd. And when it was ended, there were tears on many faces. Then, wild cheers and applause struck Don like a flood.

God is love. That is what the Bible said. And in that moment, Don Murray knew that love lies deep in the heart of every human being. And where that love is, is hope. Then and there, Don Murray dedicated himself to the service of these people, who had shown him so beautifully this greatest meaning in life.

It is on that meaning that Don’s whole religious faith, and everything he does today is based: Love and service to others.

“One must have faith, to begin with,” he says. “One must believe. It was this that pulled me through those rough days in Naples. Otherwise, I don’t think I ever would have been able to hang on.

“Doubts? Oh yes, I had doubts—loads of them. So many times, I thought to myself, ‘Why did I ever come here? Maybe I should have stayed in Germany—there I felt I was really accomplishing something.’ And sometimes, I was terribly discouraged.

“This is something that every person who has religious faith should understand. Those doubts will come when things go wrong, for we’re all human, with human weaknesses. But if your faith is strong, it will give you the strength, too, to see it through. I know it was like that for me. The thing to do is just go on working and trying—and believing.”

Working. Again and again this word appears, when Don talks about his faith. For this is another great tenet of his religion. As it is written in the Scriptures, “Faith without works is dead.” This, Don Murray firmly believes.

By profession, he is an actor. Both his parents were theatrical people, and it is a calling for which he had a natural bent. He appeared in plays since childhood, and went to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts as naturally as another boy might follow his father’s footsteps as a doctor or lawyer.

Some may feel that acting is far afield from religion, but Don doesn’t think so. “An actor, through the characters he plays, can help people to understand humanity, and bring them closer to one another in this way,” he says. “Take a play like ‘Hatful of Rain.’ It dealt with very human problems. And in revealing the way some kids fall into the evil of dope addiction, it served a constructive social purpose, too.”

But acting, for all his love of it and whole-hearted enthusiasm for it, is only the means to the end that he found in his religion.

Weak as he was, Don remained in Europe for six months’ voluntary service after his term as a conscientious objector had expired. When he came home in May, 1955, he was thin as a rail, but to a young lady who met him at the boat, “He looked terrific.” In spite of his woeful thinness, Hope Lange saw in Don Murray a quality that she hadn’t seen in the fun-loving young actor who had been courting her ever since she was a seventeen-year-old dancer, and who had written her faithfully all the time he was overseas. There was a strength and purposefulness in him that was oddly exciting, and she found herself becoming much more interested in him than she ever was before.

Don expected to have a tough time, breaking into Broadway again. But when he began to read for parts, he felt a new power in his work. He realized, then, that all his experience overseas had given him a professional asset that he had never dreamed of—the developed maturity and understanding of people that every good actor needs. He felt it when he read for “The Skin Of Our Teeth.” Famed director Joshua Logan felt it, too, when he saw him in the play—and as a result tested and signed Don for the part of the cowboy in “Bus Stop.”

And all the good things began to come his way—the best of all, his marriage to Hope while on the “Bus Stop” location. Overnight, movie and TV offers poured in.

To Don, this meant the beginning of fulfillment of a bigger dream—a dream now shared with Hope. He flew back to Italy to set up a program with the Church of the Brethren, of which he was now a member, aimed at giving a future and a place in life to the refugees, still hopelessly confined in the D.P. camps.

“These people have done nothing wrong,” Don says passionately. “They are victims of circumstances. Some of them have been there from five to twelve years! People who escaped from Communism, or through territorial changes lost their country to Communism. Due to immigration restrictions, they have no place to go. In Italy, they cannot work, because the Italian Government has all it can do to solve the problem of unemployment for its own people. So these unfortunate people are condemned to a life that has no future—unless somebody helps!

“That’s what we’re trying to do,” Don explains, his face glowing. “It’s not charity—these people don’t want or need charity. They need to feel that their lives are not a total loss, that they have a place and a purpose. To sit day after day with nothing to do and nothing to look forward to does terrible things to people. I know. I’ve seen it. Think of it—there are forty-five thousand of such people in barbed-wire camps in Western Europe today!

“Our project, HELP—Homeless European Land Program—has the purpose of buying land where these people are held and building new communities where they will be able to work, construct homes and earn their right to citizenship and freedom. We have the support of the United Nations, the Italian Government, the U.S. Escapee Program, various voluntary organizations and individuals—Protestants, Catholics, Jewish or Orthodox.”

For this project, Don contributes not only time, work and words, but a large portion of the very hefty income he’s now collecting as top Twentieth Century-Fox star of “The Hell Bent Kid.” Since Hope won a top role in “Peyton Place” and her star status is also zooming, she, too, contributes sizeable sums from her income. Recently, both Hope and Don were overjoyed when the CBS-TV show “Playhouse 90” made them an offer to star in “The Homeless,” a play about the refugees’ plight based on his own experience that Don wrote with Fred Clasel. Every cent of the $10,000 they get for acting in it will go into the initial HELP project in Sardinia.

“It’s the first project, a model we hope will be copied all over Europe,” says Don enthusiastically. “The U.N., the Italian Government and the U. S. Escapee Program put up half the money for the land, and we’re trying to raise the rest. We’ve already planted the first crop, and hope to move the families out of the barbed-wire into their own homes as soon as we can pay off the land.

“All contributions are gratefully received,” says Don with a grin. “Send ’em to HELP, 22 South State Street, Elgin, Ill., and make checks payable to Brethren Service Commission.” Incidentally, every cent goes directly to the refugees. Personnel, administration and promotion are paid for by the Brethren Service Commission, the Congregational Christian Service Commission, and the Murrays.

“I know a lot of people wonder why I joined the Church of the Brethren,” says Don. “Well, I look upon a church as a place of fellowship. A house of worship is just a church building. It’s the spirit of the people inside that counts, not the building or type of faith. I found that these people thought and felt as I did, and their faith wasn’t a matter of words. They lived at it and worked at it. That appealed to me. And I think when you find that kind of fellowship in which you feel at home, no matter what the denomination, that is the place to be.”

Don sighed as he added, “I’m so tired of reading about how I don’t smoke or drink. It’s true that I don’t smoke or drink because my church doesn’t approve of it. But it’s played up so much, as if it were a big thing. It isn’t important. That’s a negative attitude. And religion should never be based on negative thinking.”

Getting on his feet and waving his hands for emphasis, there’s no doubt that Don is now off on a subject he feels pretty hot under the collar about. “It’s the whole point,” he explodes. “Religion should be positive. It should be a matter of working, not just sitting around and waiting for things to happen.

“Just look around—are the evil-doers, the militarists wasting any time? The time to put religious faith to practice and work to bring peace and freedom to the world is now—and not when a war hits us!”

As a conscientious objector, Don feels like his church, that this is his fight—a fight to prevent war with positive action in relieving the distress caused by war and bringing hope and faith in a better way of life.

Among Don’s cherished souvenirs, along with the track medals he won as a boy and impressive acting awards, is a strange memento. An old pair of socks, half made of darning. They are his socks. The darning, a careful, expert job, is the work of a Naples lady, who, with her niece, took Don into her home and nursed him, fed him and mended his clothes when he was too ill to look after himself. “I keep those socks as a reminder,” he says. A reminder of the good in every human being. A reminder that working to bring out that good is the most rewarding, most soul-satisfying purpose that another human being can have.

“A Catholic priest put into words what my religion means to me, much better than I can,” says Don. “Not long ago, I was privileged to hear Father F. A. Morlion, who is President of the International College of Social Studies in Rome. And in these words, that I’ll never forget, he summed up exactly the way I feel: “We cannot see God. We cannot have a conversation with God. We cannot hurt God or help God as a person. But what God has done is to put people on the earth who are here in place of Him to represent Him, and it is in these human beings that God expresses Himself.

“ ‘The only way you can serve God is to help human beings, and the only way you can hurt God is to hurt human beings’ ”

THE END

—BY ALEX JOYCE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1958

No Comments