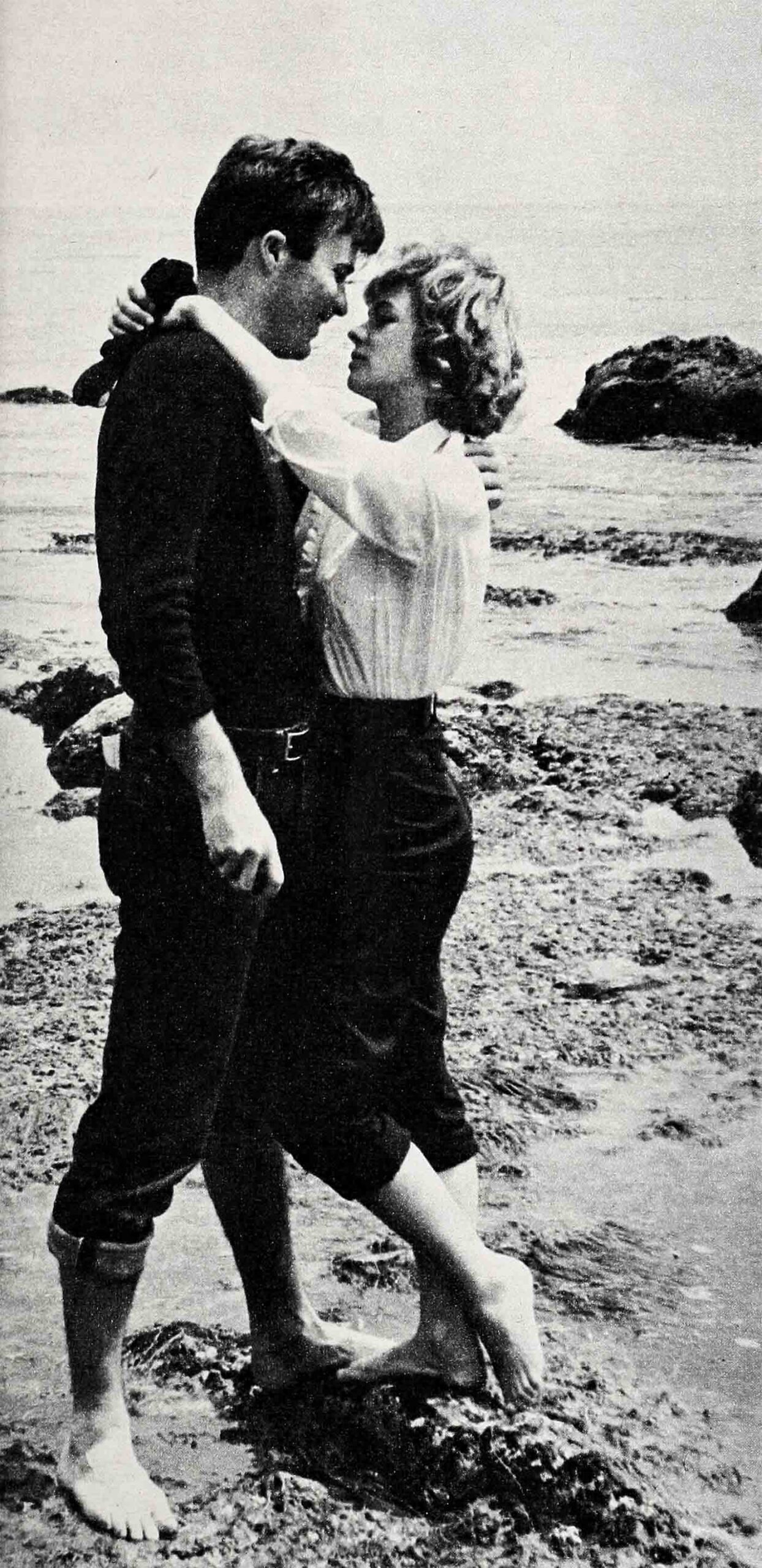

Judi Meredith & Barry Coe

All that day, as we tried to be happy, I wanted to cry out, “I love you, Barry. Why isn’t that enough?

I listened to the sound of the waves breaking on the shore. And then I heard his gentle sigh—filled with a sadness I had never noticed before.

It was like those waves being drawn back to sea again. Barry, his arms still around me, leaned back to look into my face. Then he brushed my hair back with one hand. “Judi,” he said at last. “Judi? Let’s make it a good afternoon. Let’s try to be a little happy. At least, let’s try.”

I took a deep breath and tried to smile. “All right,” I said then, but my heart begged, Barry, why? Tell me why this is happening, why it is over, and it will be all right. Or, at least, it will be a little better.

But I could not say it. I could not make myself ask that question. “What shall we do?” I asked.

“What would you like to do?” he said.

“I—” What would I like to do . . . I’d like to turn the clock back. I’d like to have never met you. No, no, I don’t mean that. “I—why don’t we sit in one of those rowboats over there and pretend—like we used to—” my voice caught, but I forced myself to go on, “pretend we’re in the yacht we dreamed about—going to Costa Brava, or—or anywhere. Why don’t we do that?”

“Fine,” he said, taking me by the hand and leading me to the group of boats, bobbing on their moorings. “What will you have?” He bowed ceremoniously. “A red one, or a white one, or—”

“Let’s take that one.” I pointed out a rainbow-colored rowboat. Someone had really enjoyed painting that boat. Every conceivable color had gone onto it. Barry helped me into it, and we sat down facing each other.

“All right,” he said, and assumed the serious pose that was part of the game, “now, where would you like to go? Portugal? The Riviera? Or, how ’bout up the Amazon?”

“Anywhere,” I said quickly, “anywhere will be all right with me.” For today I was acutely aware that the boats weren’t really going anywhere. They weren’t going anywhere today, or tomorrow, or ever, as far as we were concerned.

“You’re not in the mood for this today, are you?” he asked. “You’re not enjoying it.”

“No,” I said. “No.”

“I’m sorry,” he told me then, and I knew he was saying he was sorry for a lot of things, a lot of things more important than whether or not I was in the mood for a make-believe voyage.

But his being sorry didn’t make it any easier. If anything, it made it even harder. Because, if he were sorry, if he really were truly sorry, and I believed he was, then why?

This was the last time we saw each other, after having gone together for a year.

The first time I saw Barry I didn’t think twice about him. Not really. . . . I was aware of him before we met. I’d seen him on screen in “Peyton Place” and thought him attractive, extremely so. But the first time we met, last year on the night of the “South Pacific” premiere, we were both dating someone else.

My date that evening was Floyd Simmons. I’d had to work late and couldn’t attend the premiere, so Floyd picked me up at eleven and we went straight to the Beverly Hilton Hotel, where the studio was giving a party. We were seated at a table with a few other couples, among them Barry, whose date was a beautiful actress, also under contract to Twentieth.

It was a big party, the room was decorated in bright colors, the women were in their loveliest formals, the men in dinner clothes. There was a real fiesta-type atmosphere about it. Barry and his date were obviously having fun, but suddenly I felt that someone was staring at me. That someone was Barry. There he was, sitting at one end of the table, all dressed up and looking much too handsome, with a beautiful girl at his side, and he kept looking at me! But the most irritating thing of all was that I couldn’t help looking at him, either. I didn’t want to look at him, but, somehow, I had to. By the end of the evening I felt like a child. I didn’t like feeling this way, and I blamed Barry for my loss of poise. I don’t like him, I told myself. I don’t like him one bit!

I was still feeling a little foolish about “making eyes” at Barry several days later, when I got a message that he had phoned and would call back. He kept calling back and I kept missing his calls. I didn’t understand my attitude at the time, but looking back I realize that deep down I probably wanted to talk to him very much, but was fighting it because I felt his “type,” the tall, broad-shouldered Adonis type, didn’t make a very stable companion. Also, I think maybe I was afraid he’d sweep me off my feet—if the first time I’d seen him was any sample.

A week passed. And then one night my phone rang, and it was Barry again.

“Say, haven’t you gotten my messages?” he asked. “I’ve been telephoning you all week!”

“Yes, I know.”

“Well, well . . . how are you?”

“Fine.”

“Ah . . . that’s nice . . . Listen, Judi, I understand we’re going to do some publicity work for the studio together next week. Don’t you think it would be a good idea if we went out first and sort of got acquainted?”

“Not particularly!”

“Oh . . . well, I just thought it would be better if we spent some time together . . . then it would be easier on the photographer when we actually shoot the pictures.”

I just sat there. Let him talk, I thought.

Finally, he said softly, “Look, how would you like to go to the beach this Sunday? You don’t have to stay long. I’ll bring you home any time you say.”

What could I do? I made the date. It was arranged for him to pick me up at ten in the morning. But on Sunday, a TV rehearsal came up and it slipped my mind entirely that I had made | a date for 10 a.m. until I got home and saw him there. He’d been sitting there waiting for two hours. When I tried to apologize, he wouldn’t let me. He said he realized it must have been something important that detained me and let it drop right there. His attitude was so unexpected, I couldn’t say a word.

I threw my beach towel and stuff in the back seat of the car and off we went. We stopped for lunch. Again I gave him a difficult time. I guess I had a guilty conscience for having acted so badly, when he turned out to be so sweet. To cover my own embarrassment, I decided to make him even more miserable by pretending to be something I’m not. When we sat down to order lunch, I started talking about all sorts of things that really didn’t interest me—superficial things—how much I enjoyed parties and how I just couldn’t wait to go to a big premiere the following week. I kept rattling on, hoping I’d get him mad enough to be angry with me, but he just sat there so good-naturedly that I finally sighed, dropped the act and my defenses and took a good look at Barry Coe. I liked what I saw.

Hours later, when he took me home, we both knew something wonderful had happened. That day at the beach was the beginning.

We became a steady item. What did we do during those 361 days of steady dating? A lot of things. We went to shows, parties, took long drives, went fishing, water skiing, boating, surfing. Sometimes we were with lots of other people, but mostly it was just the two of us. It really didn’t matter what we did, where we went. The only important thing was being together. My folks live up in Oregon and, except for the time when my sister and I shared an apartment, I’d been alone, on my own. Then I met Barry and I wasn’t alone any more.

From the very beginning, we had so much in common, the same likes, dislikes, hobbies, attitudes, careers. I think maybe it was more that we shared the same dislikes, than likes, that cemented the bond. Neither of us really enjoy big parties and making the Hollywood social scene. We both love sports, the outdoors, just being able to walk down a beach, or ride in on a wave, or skim over the water on skis, with time standing still and no worries about being seen or making an impression or caring about anything except being with each other.

We enjoyed just talking for hours and hours without letup, about life, what we wanted . . . talking philosophy, discussing everything under the sun. We took up painting, and I was interested in Barry’s pet hobby, photography. He loves it and takes marvelous pictures. A typical date, when we weren’t working, was sheer heaven. We’d leave the city about seven in the morning. Barry would pick me up, we’d stop and have breakfast and buy a newspaper and he’d give me half, and we’d sit in the restaurant like an old married couple, he with the sports page and the editorials and me with the woman’s section and the gossip columns. Then we’d get into his car and tell each other what we were reading, laughing at silly items. We’d keep driving until Barry spotted a background or something that looked interesting. Then he’d stop the car and we’d take fifteen minutes getting all his paraphernalia out of the trunk. Like a director, he’d pose me, picking a daisy, or climbing a fence, or looking out at the horizon. We’d stay away all day and come back in time for dinner. We’d stop at a market and buy some steaks and things. We’d usually go back to his place because he has a whole special developer and darkroom setup.

While I made dinner, he’d pull out all the rolls of film and start the developing process. We were both such nuts, we couldn’t wait to see what he’d shot. He’d develop the pictures, then let them dry, then print them and then, as if that weren’t enough, we would make the job professional by following through on the last step—mounting the works of art on stiff paper matting. Sometimes we’d stay up until three or four the next morning until his living room looked like a picture gallery.

Many times, instead of going out, we’d just stay at home and talk. We didn’t need the stimulation of bright lights and crowds. We’d talk and talk about lots of things, like owning a boat someday and how we’d furnish it—we never went into details about a house—but we did dream of a boat. We knew exactly what color it would be and we’d plan imaginary trips in it. Sometimes we’d try and make up names for all the children we were going to have—you know, crazy things between two people.

We celebrated the New Year together, and 1959 started out as wonderful as 1958 had ended. We were pretty busy working, but still we kept seeing each other all the time. Barry did two pictures practically in a row, and I was busy with my television work, and January slipped into February and March and April. And all was well. At the end of April there was a lot going on. My older sister Mab had set her wedding date. We were to be attendants. Mab and Stan and Barry and I had become quite a foursome. It was fun planning things to help celebrate the coming event. Then, on April 23rd, I got a call from home that my grandfather had passed away. I went home to Portland. Oregon, for the funeral, to spend some time with my family. I was gone for a week, and during that time Barry called me at home, sometimes two and three times a day.

It was during one of those phone calls that I detected a difference in him. He was pleasant and very considerate over our loss and yet, inside me, I knew something was wrong, that he was trying maybe to tell me something, but that he couldn’t quite get out the words. It was a weird, strange feeling. At first I thought maybe I was being overly sensitive or intuitive, but, being honest with myself, I knew that Barry and I were too close for me to be deceived by something that didn’t exist. It was as if I had an unseen enemy. I couldn’t put my finger on what was wrong.

When I got back to Los Angeles it didn’t take but a few seconds after I saw Barry to know that I had been right, there was a change in his attitude, a difference. We talked about a lot of things and we left a lot unsaid. But I was afraid that it was over.

Two days after I came back from Portland, my sister got married. Barry was the best man and I was her maid of honor. She was radiant with happiness, but, as I stood at the altar with her, my eyes met Barry’s. I was glad that it was customary to cry at weddings. . . . Just before the ceremony, he had finally put it into words.

“Judi,” he’d said, “it’s over. You know it and I know it, so let’s not talk about it. But there is one thing I want to do. Maybe it’s crazy, but I want to do it. One last thing to bring us full circle. Judi—let’s go to the beach again, and let’s pretend that nothing’s happened. Let’s pretend. . . .”

And so we had come to Paradise Beach, to our beach. We sat in the rowboat that was never going anywhere. We held hands, and we looked at the sea. But I couldn’t laugh. I couldn’t even smile

“You’ve got to try,” Barry said, almost fiercely. “I want to remember you happy.”

So I tried. “You always wanted to be a dancer,” he said. “Pretend you’re Pavlova,” and he boosted me in the air. “Point your toe!” he said exasperatedly, getting red in the face from swinging me around.

Suddenly, I laughed. Everything he did, he did with such intense concentration, as if it were a matter of life or death. I laughed until he set me down, and I lay weak with laughter on the sand.

“. . . We could carve our names in a heart again, ” I said then, looking around me, “if you could find a stick. And we could build another castle. . . . Oh—there’s a perfect stick!”

One last time, we drew the heart and put our names inside of it. One last time, we shaped little rooms out of the damp sand. Then we waited for what had always happened to happen again. Each wave came a little closer than the last, until the big one that, in one sweep, destroyed our castle and erased our names. They would never be entwined again. Why? I will never know.

I shivered. The sun had set, and there was a chill in the air. “I’ll take you home now,” Barry said.

And that was the last time I saw him. Now, the ragged edge of hurt is gone. I don’t sit home alone any more. I go places and do things. Once in a while, though, I hear a song or see something that reminds me of when we were together. Then I ask myself, Was it really love? I know the answer. Yes, it was love. Then I think, Well, if it was love, shouldn’t that have been enough? And the answer is: Sometimes even love is not enough. For marriage, you need a combination of so many other things. . . . I thought once we had them all. Now I know I was wrong.

THE END

BARRY COE CO-STARS IN TWENTIETH’S “A PRIVATE’S AFFAIR”; HE WILL ALSO BE SEEN IN PARAMOUNTS “BUT NOT FOR ME.” JUDI MEREDITH IS UNDER CONTRACT TO CBS-TV FOR THEIR NEW SERIES, CALLED “HOTEL DE PAREE.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1959