Big Noise From Guy Mitchell

One morning last fall the middle-aged owner of a small ranch in Tarzana, California, prepared for a trip. From his stable he led a brown saddle pony into a horse trailer which he hitched behind a maroon sedan. When all was secure a woman came out of the house and joined him in the front seat of the car. They drove out of the yard and headed for the. first mountain pass leading out of the valley to the east. Mr. and Mrs. Albert Cernik were on their way to Las Vegas, Nevada, to see their eldest son. The happy, husky boy who had always wanted to be a cowboy had somehow become the newest singing sensation of the entertainment world.

He wasn’t called Albert Cernik, Jr., any more. Now he was known as Guy Mitchell. They knew that all over the country, in big theatres, hotels and nightclubs, his singing was in demand. He had even sung in England. They knew that he made records which sold by the millions and they knew that he made pictures in Hollywood. Mr. and Mrs. Cernik were still a little dazed about all this and about the Tarzana ranch he had bought them because he wanted his father to retire from work.

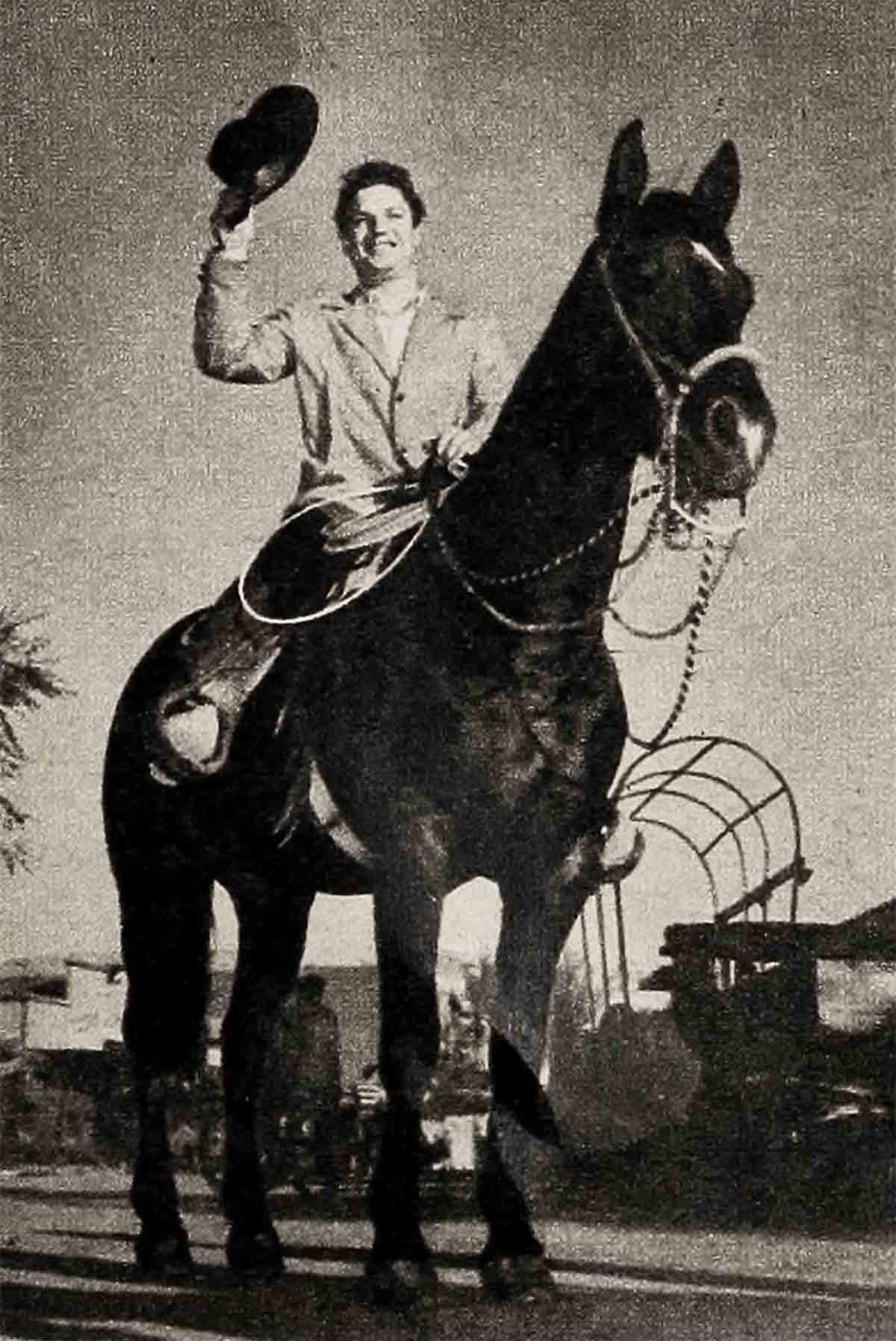

Sometimes they even found themselves thinking of this Guy Mitchell as maybe a stranger. That’s why, when he had telephoned them to be his guests at the Flamingo hotel in Las Vegas where he was now playing, they were secretly pleased when he also begged them to bring his pony along so he could do some riding. That boy, always crazy over horses, they knew well, no matter what you called him!

That’s Guy Mitchell, a surprise to most people, even to his own folks—but a pleasant one.

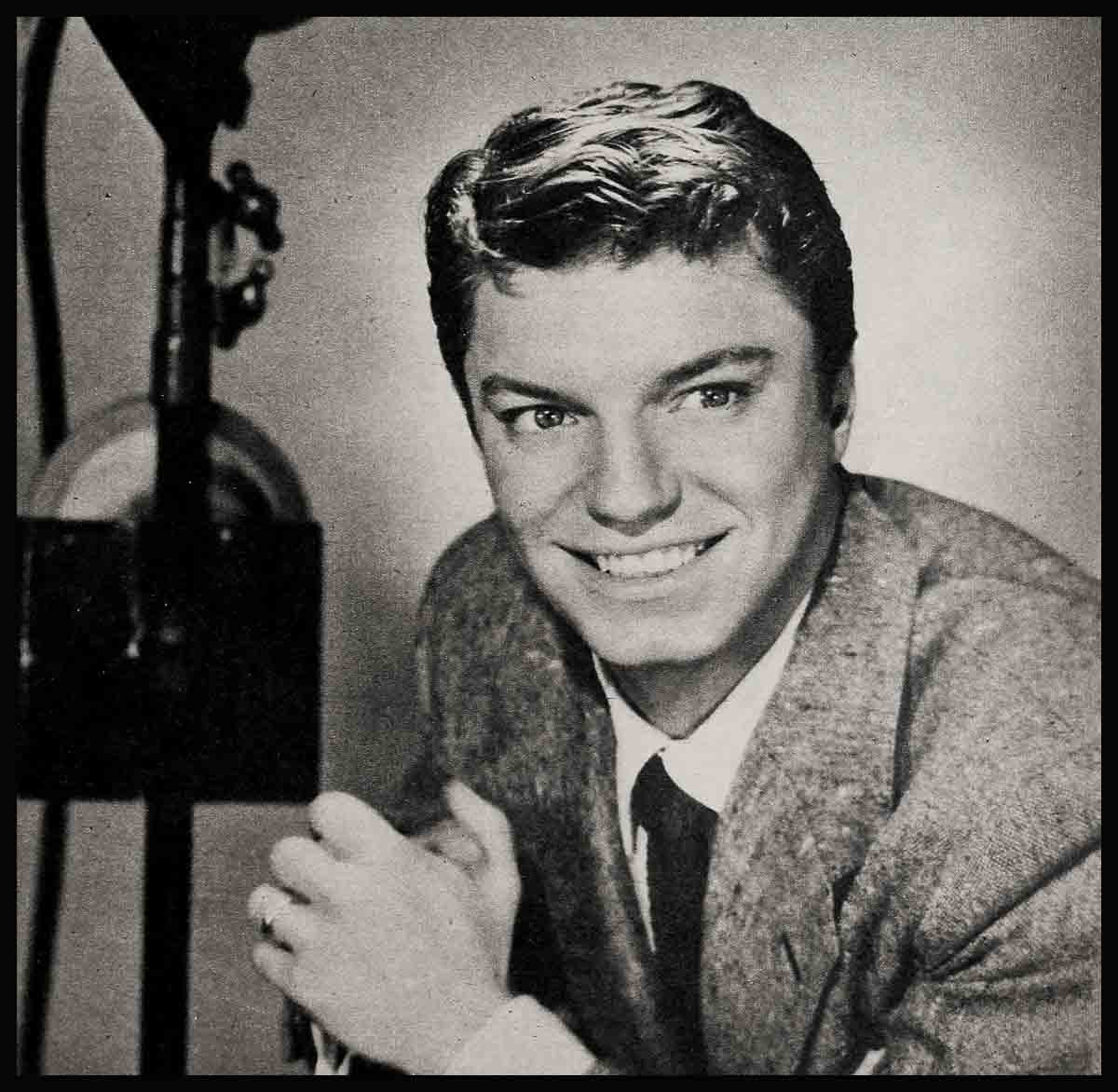

You’d think that a boy who actually broke wild horses to the saddle at the age of fourteen would be a rugged-looking customer by the time he reached his middle twenties. Guy Mitchell is. He stands medium tall, weighs 175 pounds, has a heavy cast to his features and probably the biggest pair of fists in show business. Extraordinary fists which can probably check a horse dead when wrapped around a pair of reins. But the face smiles easily into blond, blue-eyed friendliness and those fists open to become unusually expressive hands when he is singing in a baritone that can boom or croon over a range of two and a half octaves. Most characteristic is a wholehearted impulsiveness about everything he does. When his mother and father got to Las Vegas he not only fell on their necks with joy but had to run back to the trailer and kiss his horse, Scotch Boy, as well.

This combination of outer strength and inner warmth makes for a telling personality when he is before the public. He bounces onto the stage and hits his full singing stride within the first three notes. As an English theatre manager put it: “He works close; he reaches right out from the stage to tap the shoulder of the fellow sitting in the last balcony seat.” In his first two movies, Those Sisters From Seattle and Red Garters, it was quickly decided by his producers to let him be his natural self rather than make him conform to any specifications of the writers or directors. Even when he is not seen, but just heard, as in his recordings, most of his personality comes through in his voice. “He sings inside of you,” the song experts say when talking about his style.

Guy’s first real taste of success came only three years ago when he recorded “My Heart Cries For You,” his sixth platter for Columbia Records. It has sold almost two million copies. Since then, with such hits as “Sparrow In The Tree Top,” “The Roving Kind,” “My Truly, Truly Fair,” “Feet Up, Pat Him On The Po-Po” and “She Wears A Red Feather,” the cumulative sales of his records have reached the ten million mark. Figures of this kind, including the multi-thousand dollar salaries he receives today for his radio, TV, theatre and nightclub appearances still awe him. He wants nothing to do with the business end of his work; the figures mentioned in the checks and contracts are always for amounts of money which convey little meaning to him. After all, just before he made good as a recording artist his income was in the sub-low brackets; he used to find it difficult to pay a New York landlady who asked only $5 a week for her room. She would be sad for months about him, generally two months’ worth of sadness or $40 in back rent.

When he was in New York his only income came from making demonstration records for songwriters who nowadays prefer to submit their compositions to music publishers in this form. Guy, made his headquarters on the sidewalk in front of the publishers’ offices on Broadway and you could get him to sing for five dollars a song—less, if you cared to bargain. One afternoon he cut his regular rate to help an impecunious songwriter with a novelty tune. The writer sold the song and it became’ one of the biggest hits in the history of popular songs. It was “Rudolph, The Red-nosed Reindeer.” The writer made a small fortune out of it. So did almost every artist identified with it. Guy, the first man ever to sing it, got two dollars for his efforts, and as he says, “I could use the money, too.”

Guy, whose folks are Yugoslavian, was born twenty-seven years ago in Detroit on Washington’s Birthday, but he has been caught telling lies in his time. His mother was the victim of one of his biggest fibs. While attending Mission High School in San Francisco after his family came west he would come home day after day with various injuries—skin lacerations, muscular sprains and even suspected concussions. His story was that he sustained all of this damage in football practice. The truth, as she found out years later, was that he had taken up bronco busting.

He was spending his spare time at the local stockyards, helping the cowboys in their corral work and trying to ride the wild horses which were occasionally shipped in. As Guy’s skill grew, he seriously decided to take up rodeo riding.

He was only fourteen when he spent $25 for an outlaw colt headed for the glue works because nobody could break it to the saddle. A month later he was able to sell it for $100. It was a well-behaved animal, amenable to final training. That summer and the next he found cowpoke work on ranches in the San Joaquin Valley.

Guy lied to his mother because the family had agreed that his destiny was singing. Whenever there was a spare dollar or two it was used to pay for singing lessons. This didn’t bring much training because spare dollars were rare, but the idea was there. He knew his parents wouldn’t consider it a bit sporting of him to go around courting a broken neck with his horse wrangling.

But he could not stop. He had western fever and he still has it. He even apprenticed himself to a saddle-maker when he was in his teens because he loved the feel of leather. He still makes all his own riding gear. Playing anywhere in the west he will usually be seen sporting riding garb. If he happens to be missing in a new town his road manager, Marty Horstman, checks saddle and leather stores first. Invariably, he finds Guy at one of them. That little ranch he bought for his parent in Tarzana is not the last land transaction Guy plans; there will be another one some day, in Nevada probably, and it will be for a real cattle outfit, he says.

Guy’s family moved from Detroit to California when he was eleven, living in Los Angeles for a year before going on to San Francisco. At that time Guy’s singing, overheard by a scout while he was riding on a Greyhound bus, won him a grooming contract at Warner Brothers Studio and regular singing assignments at the studio’s radio station KFWB in Hollywood. Nothing came of this nor of subsequent radio work as a. singer in San Francisco with Dude Martin on his KYA and KGO radio shows. Guy left Dude to join the Navy in 1945 and returned to Dude in 1947 feeling that nothing was any different except the feel of a horse—he hadn’t been on one for sixteen months. He decided he could never stay away from horseflesh this long again. During his tour of England, playing London and the provinces, one of his manager’s principal duties was to hire horses and bring them to the stage door. Guy hadn’t the time to go riding but at least he wanted the satisfaction of sitting a mount once in a while. When there were no horses to be had the manager appealed to mounted policemen for their co-operation. They would always understand and plod their steeds to the stage door to dismount and let Guy climb on.

Late in 1947 Guy switched from Dude Martin to Carmen Cavallaro’s orchestra as a male vocalist. The next summer when Carmen’s outfit went to New York for its annual engagement at the Astor hotel, a date Guy had been looking forward to all year, he had a serious attack of laryngitis and a bad case of ptomaine poisoning. Cavallaro gave him two weeks’ salary and a plane ticket home to San Francisco for a rest. Guy cashed in the ticket, and with a total bankroll of more than $500 figured he had enough to invade the sanctums of those who control the music world and prove to them that he deserved their support. For a long time he got no closer than the busy curb outside their offices.

There were moments of glory. One night, while singing in a small night club, a $50 bill was thrown at him by a customer. In the fall of 1949 he placed first on an Arthur Godfrey Talent Scout Show. This seemed to impress nobody and he was soon back at his sidewalk stand.

One day a tunesmith named Ned Washington asked Guy to make a demonstration record of a song called “My Foolish Heart.” It was accepted for publication by Eddie Joy, vice-president of the Santly-Joy company, who liked Guy’s voice and wanted to meet him. Joy also manages singers and is credited with master-minding Mindy Carson to top recognition. He placed Guy under personal contract and told him to study the leading vocalists for guidance toward achieving a warmer and more personal style of singing.

Joy obtained the Columbia Records contract for Guy and his career really got under way when “My Heart Cries For You” began tear-jerking buyers into the record stores at the rate of a quarter million a month. Guy, who was still faithfully trying to figure out what a successful singer did to a song to make it a hit, was told he could stop now; all he had to do was sing like Guy Mitchell.

If you are a young American citizen, male, who can sing like an angel and ride like the devil, you might as well start house hunting in Hollywood—you’ll be out there sooner or later. Guy’s records caused talk and the talk got to the ears of talent heads at Paramount Studios. Both of his pictures are Technicolor musicals. In Red Garters co-starred with Rosemary Clooney, Joanne Gilbert, Pat Crowley and Gene Barry. The cast of Those Sisters From Seattle included Rhonda Fleming, Agnes Moorehead, Teresa Brewer and, again, Gene Barry.

During his months at Paramount he got to know everyone in the studio and had only one unhappy day. This was the afternoon he was handed his new cowboy outfit, made in resplendent white and tan, for his role in Red Garters. Strictly a blue jeans man himself, Guy was ill at ease in his new costume. He slunk in and out of doorways and killed time on the set in dark corners.

His parents and his younger brother, Donald, who is seventeen, paid him a visit at the studio. They met Bob Hope and afterward Guy thanked him for being so affable with them. “That’s all right,” said Bob. “You just be nice to my folks when they come. I’m no fool.” This, according to those who know Bob, is no mean. compliment to Guy’s talent and his future, even if it sounded like kidding.

It is fairly certain that for the next few years he is going to be a busy boy; he is one of the most solidly booked entertainers in the world, and in every medium of show business. Working so steadily and with so many different kinds of performers has extended Guy’s talents. He used to confine his work to singing. Now he has added some dance steps, does nice things with a guitar and has developed an easy, conversational relationship with his audiences. There may be more to come. He has been caught practicing tumbling tricks, acrobatics and bouncing about on a trampolene like a circus clown.

His only serious illnesses occurred before he was seven years old when he had pneumonia a couple of times. Since then his health has been perfect. He can sleep up to fourteen hours a night, preferably on what he calls a “basketball court”—two three-quarter beds shoved together. He likes to read, but because he hasn’t much time he reads only best sellers. He insists that he was a good student in school but his mother remembers him as “just a passing one.” He was a half credit short when he left Mission High School in San Francisco. He recently went back there and sang for the students in the assembly hall. Afterward, principal Alvin C. Morse awarded him the missing half credit.

In October, 1952, he married Jackie Loughery who was Miss U.S.A. in the annual Miss Universe contest at Long Beach, California. The cast and crew of Those Sisters From Seattle gave a surprise luncheon for the couple at Paramount on their six months wedding anniversary. Five months later they had separated. Jackie is suing for separate maintenance, charging cruelty. Guy has said, “I want to be married. I want children. When I get my ranch my life won’t be complete until I have a wife and children on it.”

THE END

—BY LOUIS POLLOCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE MARCH 1954

No Comments