A Rage To Love A Rage To Live—Steve McQueen

They say many things about Steve McQueen. Those who don’t like him say he is stubborn. Those who do, say, “He isn’t stubborn. He simply knows what he wants and won’t take anything less, that’s all there is to it.”

All admit, however, that McQueen is straightforward, talented and so imbued with ambition that his every waking hour is a relentless, sixty-minute assault on life. Yet, he is gentle until aroused. Then he is ruthless. But some nights he screams in his sleep. . . .

In a rare moment of introspection recently, Steve looked back on his life and was so shocked at his past that “I damn near cried.” That he survived it at all he considers a phenomenon. “But that I emerged without irreparable damage to my mind and my body is a miracle,” he said thoughtfully. There are a few close friends of McQueen, however, who say that it will be an even greater miracle if Steve doesn’t kill himself one of these days as a speed demon.

“I’ve looked at the world through blackened eyes, through the sights of a rifle, through the portholes of ships, through the peephole from a gambling casino, through the bars of a jail. I’ll make it now,” Steve says. He once looked at the world through a Christmas holly wreath while he was confined to a correctional institution. “I hated everything I saw, including Santa Claus,” Steve remembers.

But McQueen insists, as do many others, that the Boys Republic center at Chino. California, where he was placed, is not a reform school. The fact remains that Steve was put there in his early teens because his violently rebellious behavior was considered incorrigible. It was an attempt to reform his outlook on life and on the rest of the humans that go with it.

To better understand the kind of man Steve McQueen is today, it is necessary to examine some of the circumstances and incidents in his life that have made him what he is.

For example, McQueen’s reference to emerging from his teens without “damage to mind and body” is a reference to a boyhood that is without question the most frighteningly terrifying of any boyhood of any star in the long history of Hollywood.

A friend of McQueen’s once said that when Steve was born and held up by his heels by the doctor and spanked by the physician until he cried, in all probability McQueen didn’t cry at all—he snarled.

“But not even a five-minute old infant snarls for nothing,” the friend added. “You see, it became quite obvious later that McQueen had come into the world unwanted by anyone. And I can’t imagine any more dreadful beginning of a life than to come into the world unwelcomed.”

Memory of home

Most men struggle to recall the first memory of their lives. Some say the first thing they remember is the smiling face of the mother. Others recall the oddly retained image of a toy or a stranger or a place or a song.

In this respect Steve McQueen is like every man. He does have a first memory—of being thrown down a flight of stairs by his stepfather.

McQueen is never constant, however, with his account of what ever became of his first father. At times he has said his dad, William McQueen, was a stunt flyer who died in an accident when Steve was only six months old. On other occasions he says that his father was a pilot with the Flying Tigers in China, under General Chennault, and was shot down by Japanese planes in 1939.

But the general belief is that Steve’s father simply deserted his mother, and neither of them ever saw the man again. The flyer explanations are no doubt the remnants of heartbreaking stories Steve had to tell as a boy when the other kids asked, “Where’s your father?”

Yet it is apparently the treatment Steve received at the hands of his stepfather—a treatment approved, condoned or ignored by his mother—that drove McQueen to be tile kind of a man that he is today.

As young as he was at his first remembered beating, the boy’s hardly-formed mind did manage to become conscious of one simple ambition: to survive.

It’s been said that had Steve simply submitted to the unreasonable dictates of his stepfather, he might not have had such a bruised boyhood.

Steve manages a slow grin at that. “It wouldn’t do any good with that man. It didn’t matter at all. He apparently beat me for the sheer sadistic pleasure it gave him—which included the joy he obviously derived from my pain. I was young. I even thought of bearing the beatings, vowing simply to hold on until I was old enough to run away. But I just couldn’t. It wasn’t in me. I started to fight back.”

McQueen didn’t know it at the time, but that deep-down unexplained compulsion to “fight back” when he was a boy probably saved him as a man. For it is now quite clear that had he not rebelled, he would have grown up to be an adult with the body of a man and the mind of a vegetable.

A few years ago, during a long talk with McQueen, it was obvious that he still bore a hatred for his father that was so deep it threatened to adulterate Steve’s life and his relationships with others. And, at the time, Steve admitted that it worried him.

“I’m beginning to realize,” he said, “that I was suspicious of every person I met. I felt everyone was out to get me, no matter what I did, no matter how I behaved. That is why I’ve been a loner most of my life.”

But in the years that have passed since then, McQueen, although hardly philosophical about his boyhood, has localized the unfulfilled vengeance that still burns in his heart.

“I cannot indict the entire human race for the despicable conduct of one man. I know that now. But it still grabs me inside to hear another guy talk of the marvelous things he did as a kid, the good times he had with his parents and his brothers and sisters. It really gets me. I can’t help it.”

This is the way a man talks when the only things he can remember from the age of three to fourteen is eleven years of being beaten, cursed, flung into dark rooms without food or water, of seeking escape only to be pursued, apprehended and heartlessly thrown back at bis tormentor who would mete out even more terrible punishments than before.

“I think I was just about twelve when I started to hit back,” McQueen recalls. “My fists were small, but they were insane with desperation. You know, it relieved me a great deal just to connect with something, to feel my knuckles go hard against his body with the hysterical hope that the blows might hurt or even break the skin and draw his blood.

“I would have borne any punishment—anything, just for the pleasure of knowing that I had given back even a little of the pain he had inflicted on me. God, how I wanted that.”

By the time Steve was fourteen he was stronger and somehow he had developed an animal-like skill, a craftiness that must have come from instinctual depths. By developing a survival pattern right for the jungle, he learned that civilization had put a label on him. He was “incorrigible.”

It happened when Steve was fourteen.

His stepfather had just hit him in the face. The blow had turned his head on his neck so hard that Steve, now knocked-out on his feet, began to fall. At the moment he was, unhappily, at the top of a flight of stairs. In the next few seconds his body began to somersault down the stairs with sickening thumps and crunches as his body crashed against the edges of the steps. His arms flapped and flailed in space frantically seeking some hold for the hands. There was none.

He hit the floor at the bottom with a thud and for a moment lay in a heap, his chest heaving for breath, his vision blurred and his body bruised in so many places he did not know where he hurt most.

He lay there for a moment, his nose and mouth mashed into the carpet. The respite allowed his head to clear. He stared stupidly at the line of the floor and the legs of the furniture.

He managed to get to his feet, drunk with pain and hate. He leaned against a banister post and began to cry. Then he looked up and saw his stepfather still sneering down at him.

“In that instant,” Steve remembers, “I made up my mind that man would never hit me again. It didn’t matter whether I lived or died anymore. The only thing that did matter was that I would never, never bear the pain of his fists again.”

At first Steve’s voice was low and sobbing as he looked up at the man and said, “You ever touch me again and I’ll kill you.”

Then, from some resevoir of stamina his chest swelled with breath and he screamed:

“You hear me?!!! Hit me again and I’ll kill you!!! I swear to God, I’ll kill you!”

For the first time in his fourteen years, Steve McQueen had been seized by fury, the wild and shrieking rage that, when it takes place in the heart of a boy, turns him into a man.

His stepfather, obviously frightened at being turned on. called the juvenile police and had Steve committed to the school at Chino as an incorrigible.

For the first few weeks at the school he was exactly what they had called him, incorrigible. He made several attempts to run away. Each time he was picked up by the juvenile officers and returned.

Kindness? What’s that?

Finally one of the Chino counselors decided to work on Steve.

“He wanted to teach me the meaning of the simplest word in our language,” Steve says. “And that word was—kindness.”

Steve shook his head at the memory. “I didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. He said there were people in the world who cared what happened to me. Imagine that? I decided the real reason he was at Chino was because he was crazy. The idea that anyone cared what happened to me wasn’t just stupid to my mind, but incomprehensible.

“My Uncle Claude finally agreed to take me and let me work on his farm in Missouri, a town called Slater. I worked from sunrises to sunsets. I must have been growning up, because I began to feel a need for people my own age and I couldn’t stand the desolation of the ranch.” He ran away.

For the next three years Steve was a teen-aged derelict. He joined a freighter crew on a voyage to Central America, worked as a look-out “for a floating crap-game,” hiked and hitch-hiked his way from there to New York City and wound up in a cheap rooming house in Greenwich Village.

“The community was swarming with intellectual phonies,” Steve says, “and I didn’t understand any of them. But I did react to one thing, the right to do as you damn please, to say and think what you feel without interference. I liked that part of it.”

But Steve had an irresistible urge to move, and on his seventeenth birthday he joined the Marines after a slight delay over the question of how old he really was.

Something worth working for

Steve stayed with the leathernecks for more than two years. They not only gave him a gun. They gave him a driver’s license.

“I learned a great deal about cars. Take care of them, they’ll take care of you.” Steve says. “I was clothed well and fed well. I worked hard at being a good Marine because for the first time in my life there seemed to be something worth working for. But the one thing I discovered. that really changed my point of view on life, was justice and the meaning of it. I knew that before I knew kindness. I understood justice. You did something right and you were rewarded. Do something wrong and you were punished. It made sense.

“Toward the end of my hitch in the Corps. I began to think of what I’d do in the future.

“As vacuous as the life in Greenwich Village had been compared to my other memories, it was the only relatively pleasant period of my life.

“Once out of the Marines, I returned to New York City and the Village.”

A few months later and quite by accident, Steve was with two rooming-house neighbors who happened to sit down with famed drama coach Sanford (Sandy) Meisner. The teacher sensed, in an instant, McQueen’s natural and unflagging sensitivities and the seething, awkward, but interesting emotions that stirred McQueen to talk. Meisner suggested McQueen seriously consider drama as a career. It was all McQueen needed.

Two years after a literally desperate “career” as a starving young actor, McQueen was accepted by the Actors Studio. Less than a year after that. Steve replaced Ben Gazarra in “A Hatful of Rain” on Broadway.

“It was almost easy,” Steve says, “when there is someone to show you the way.”

His relationships with others, many of whom cared a great deal what happened to Steve McQueen, aroused a hundred dormant emotions in him. Ideals, creativity, the inexplicable satisfaction he now began to feel after difficult rehearsals, the warmth of girl friends, the hard masculine laughter he found with other men, shop talk, politics—the whole world cloudbursting on him, the quick joys of the heart, the fascinating earnestness of life in its true light and the zest and gusto of living.

One evening he and Gazarra were putting away a spaghetti dinner at a steak house near the theater.

“I looked up with my mouth full of pasta.” Steve remembers, “and stared straight into the loveliest face I’d ever seen. The face stared back for an instant and then she smiled. The face kept going, but I knew in the split part of a second that if I ever let that face go without meeting it. I’d be the unhappiest man in the world. Don’t ask me how I knew. I knew.”

McQueen got up, crashed through the jammed room and caught “the face” just as she reached the door.

He stopped her cold. He said the first words that came to his lips and they were: “All I want is the chance. One honest try.”

The girl smiled back at him. He didn’t have to explain. She knew what he was asking and she nodded her head, “All right. Call for me back stage at The Pajama Game tomorrow after the show.”

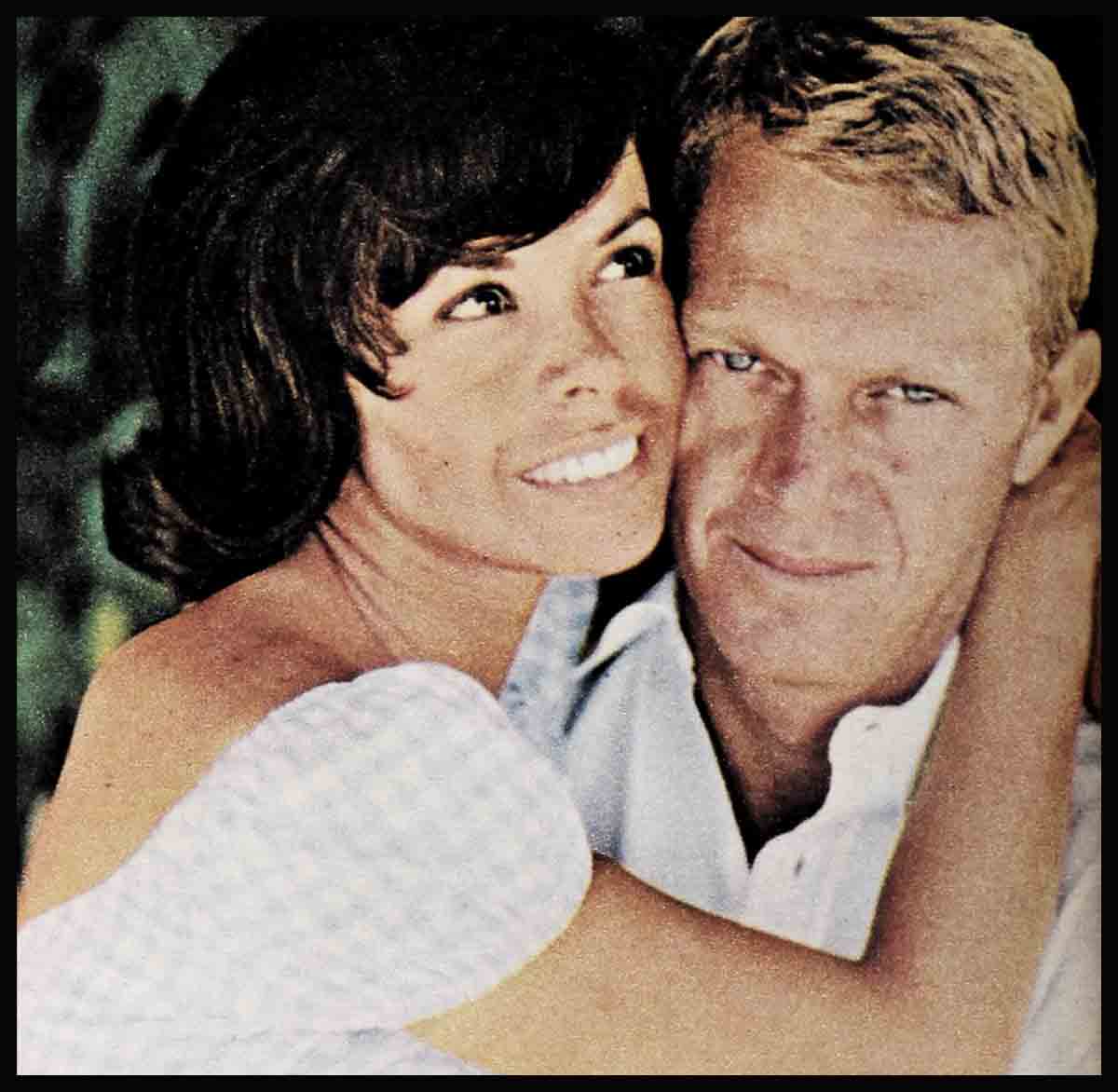

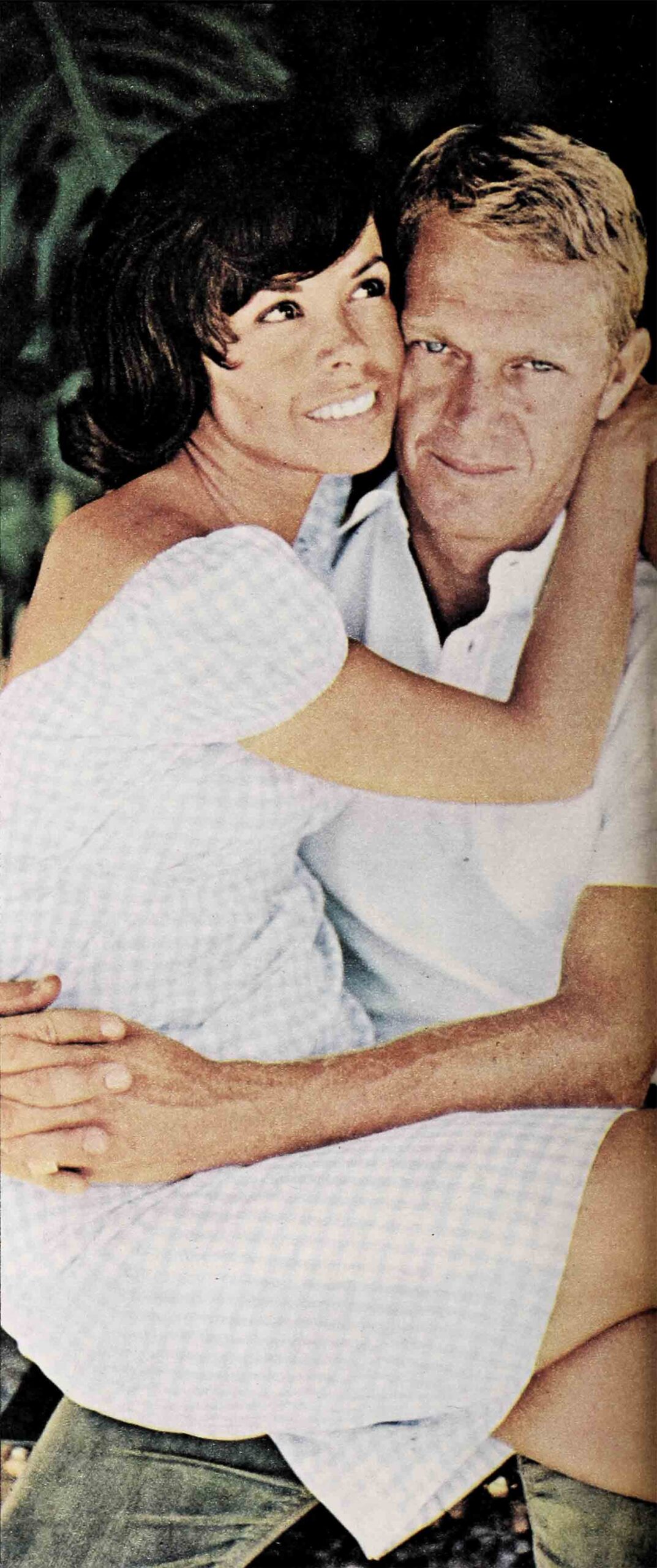

Neile Adams was small, sprite-like, with pixie hair, sparkling doe-shaped dark eyes, a sculptured figure and a laugh that rang out like little temple bells.

“By the way, you’ve got sauce on your face, she tinkled as she walked out.

So the romance began. There were many dates and many partings. Show business tried to split them up, Steve in New York and Neile in Hollywood for months. But their love was too long and too deep for even a continent to stretch it to breaking.

A yearning heart of steel

There was another bond that held them. Neile, too, had never known her father, an Englishman turned guerrilla in the Philippines during the war and killed by the Japanese.

Neile and her mother spent nearly three years as prisoners of war and somehow had survived the unspeakable miseries and torments of a Japanese concentration camp.

“But at least I had known love,” Neile says. “Steve, I learned right in the beginning, had never known it. His heart was like steel and yet I sensed the terrible yearning in him to be tender.

“I will never forget the night Steve and I were walking down a New York street. Neither of us had much money at the time and I really hadn’t known Steve for long. It was our fifth or sixth date.

“I knew that Steve was attracted to me. I guess every woman knows or senses how she’s doing with a man. I was certainly attracted to him.

“I had been telling him about some of the things that had happened to me during my childhood and I remember I had just mentioned an incident about a crush I had had on a boy when I was very young.

“Then I said I was so heartbroken over it that if my mother hadn’t loved me and I hadn’t loved my mother so much, I might never have gotten over that case of puppy love.

“The instant I said love, Steve tightened up. He suddenly walked slower and kept looking at the sidewalk.

“Then he said, ‘I have to ask you a question. Please don’t laugh.’

“I thought for sure he was going to tell me he loved me or, wildest of all after so short an acquaintance, ask me to be his wife. It was a moment of sweet suspense.

“I told Steve I wouldn’t laugh no mat-her what he asked me. But I wondered. . . .

“Then he looked up and said, ‘What is it like to love someone? What does love feel like?’

“All of a sudden I was crying. I couldn’t stop myself. Poor Steve thought he had said something wrong.

“It wasn’t that. It just broke me up inside to think of the years and years of his life he had gone without loving and without being loved. To me it was the most heart-splitting tragedy I’d ever heard of.

“From that moment on I really loved Steve and I’ve never stopped. Not because I know he needs love or because I feel sorry for him, but because I want to try and make up to him all the desolate days of his living when he had yearned so desperately for the warmth and affection so cruelly denied him.

“The happiest part of all is that Steve is worth it.”

They were married in 1956. Steve, at long last, knew he would never go hungry for love again.

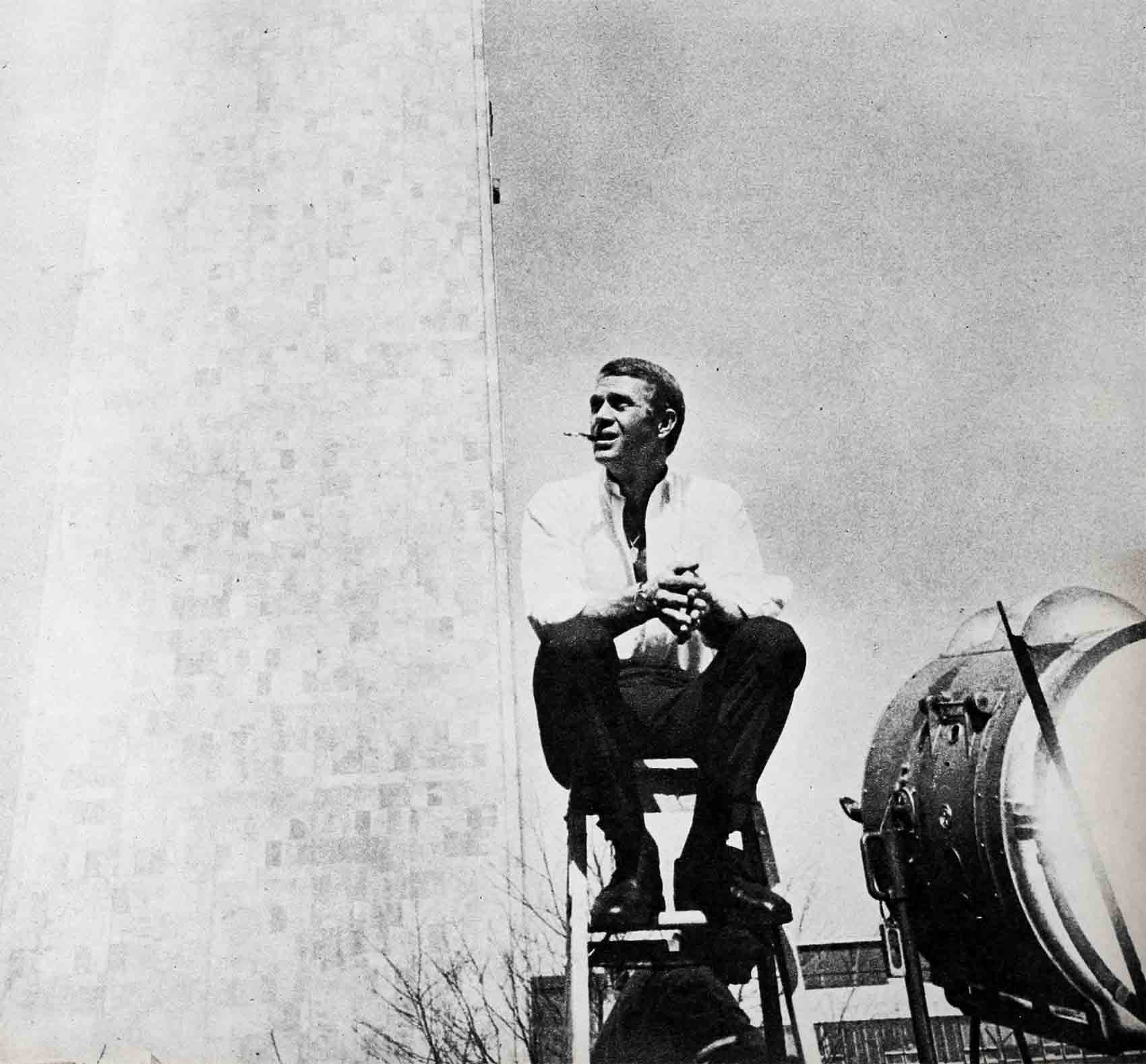

To make things even better. Steve’s career, though it didn’t zoom meteorically, began to move. From walk-ons and bit parts he went to featured roles and finally with his appearance in the TV series, Wanted—Dead Or Alive, his talent as an actor became so obvious to producers and directors that his shift from television to movies was automatic. And it was not only a successful transplant, but it also brought about certain changes in Steve.

To rid a heart of hate

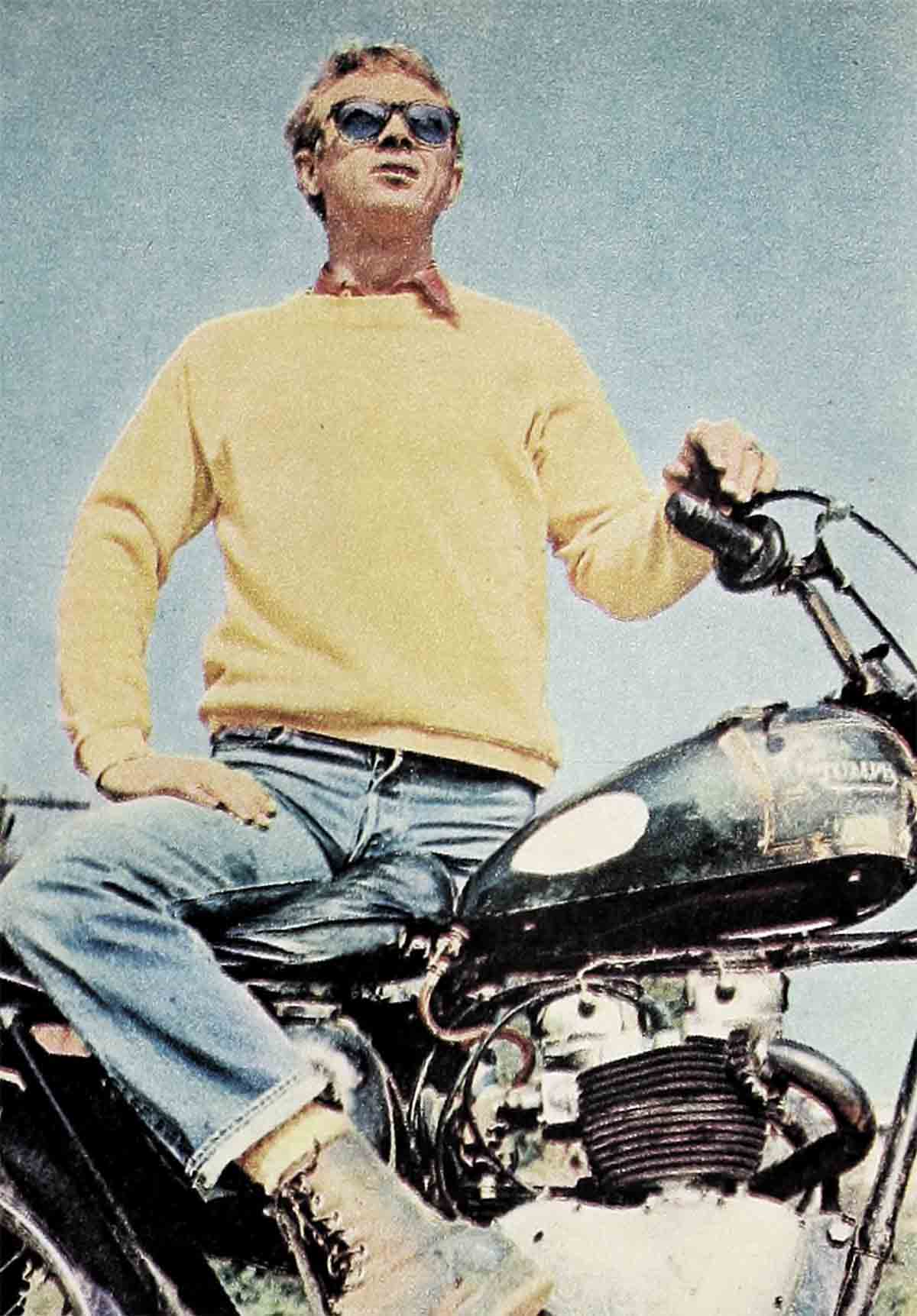

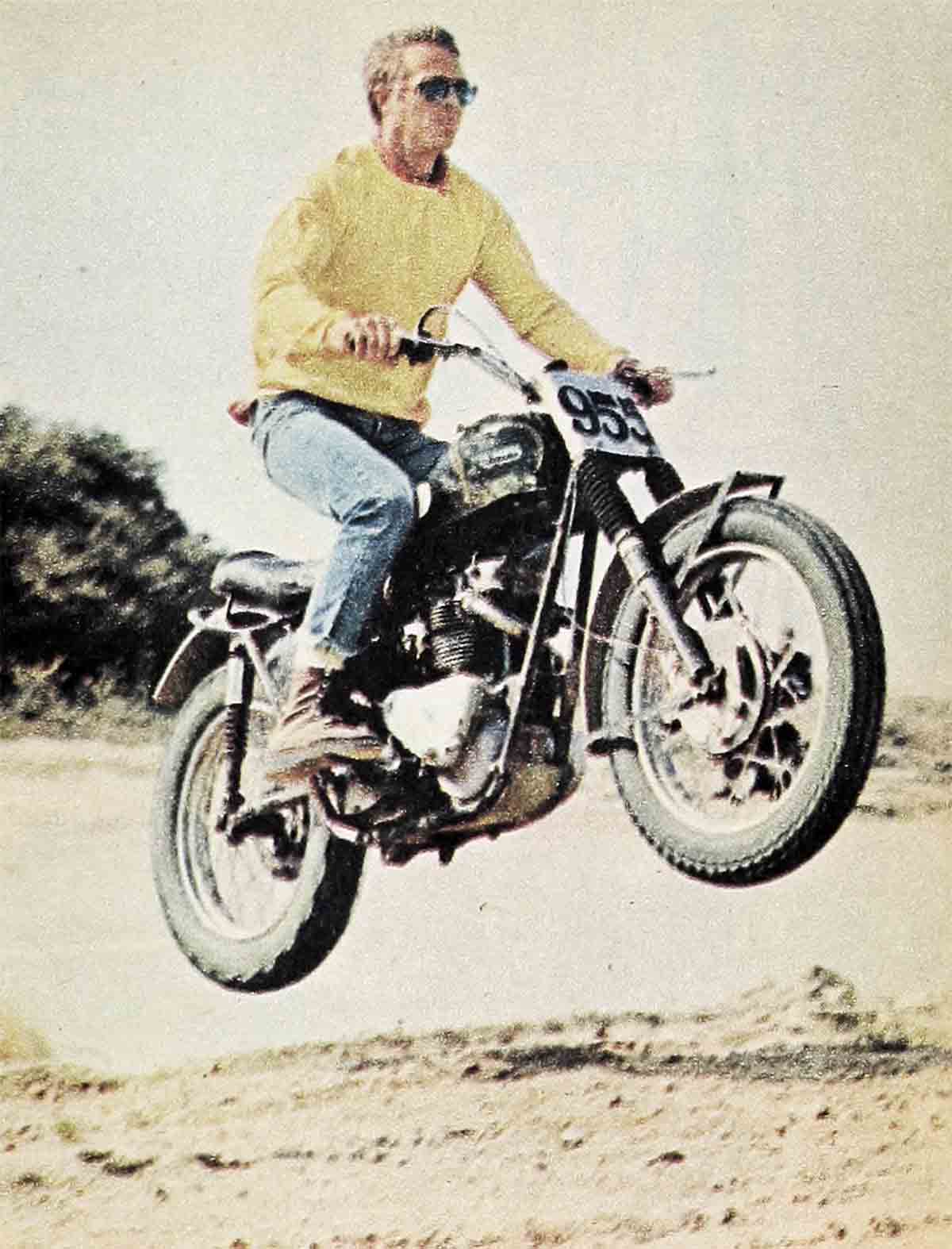

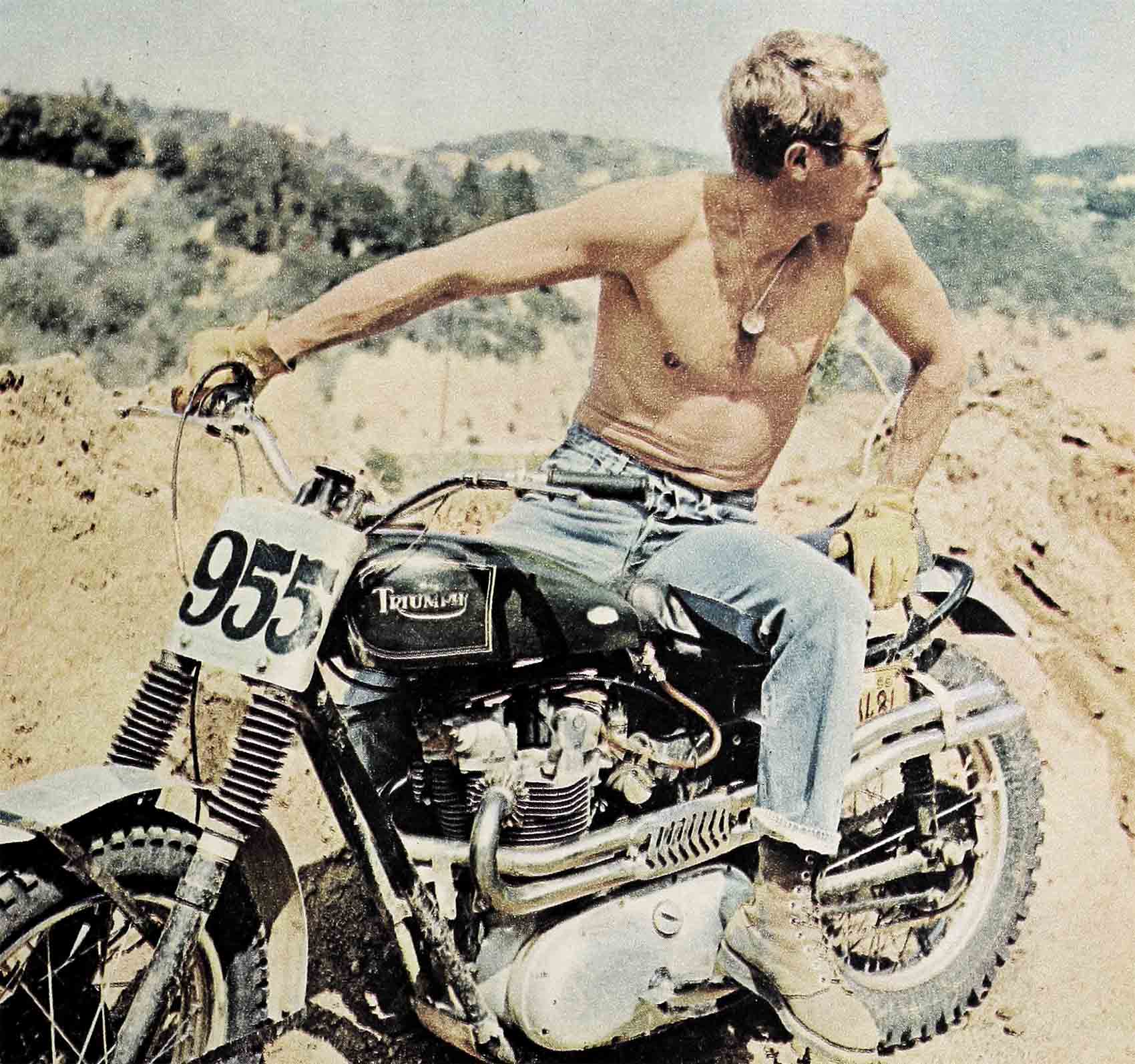

For a time his reckless compulsion for speed was the talk of Hollywood. McQueen would race anywhere there was a stretch longer than a quarter mile. Straightaway or curve, it didn’t matter. His cars, always low-slung for road-hugging on turns, zipped and swooshed by slower drivers, especially on the hills of Hollywood.

He still does it, but not so often. There was a deep, emotional reason for Steve’s craving for speed.

The longer a man hates, the longer bitterness and distrust is in him, the longer it takes him to rid his heart of it.

Steve’s outward appetite for speed and daring was, in a way, the expulsion of the hostilities that had built up inside him for so long. And though the sport has at times endangered his life, it has allowed McQueen to get rid of much of the hard-jawed resentment he felt toward those who had robbed him of a normal boyhood.

Says Steve, “I am riding out the rage in my life, because I don’t want it to hurt those I love.”

But there is an unexpected reward Steve derives from “rage races.” He discovered that perfect strangers stood in awe of his daring, his disregard for his own safety. They were fascinated. As one McQueen fan put it, “This man has a wild heart.”

Steve liked that. True, he was respected and admired as a gifted actor. But Steve’s ego feeds a little on the fact that he receives idol-worship from those who envy and admire his “incorrigible disregard for danger.”

“McQueen would race the devil if he got the chance,” an admirer said of Steve.

McQueen heard about it and smiled, “Y’know, I think I would,” he commented with a grin.

But there are signs that Steve is leveling off. At thirty-three he is beginning to welcome, eagerly, serious responsibilities, professional and personal.

He recently bought a multi-acred home in Brentwood City, the wooded Bel Air of Hollywood. He is devoting much time to the future of his two children.

More than anything, he wants to make something for himself, not just as a personality, but as a human being known for his compassion, sense of justice and a driving, articulate love for life.

“I want to be like that, not just for myself, my wife and my kids, Terry Leslie and Chad, but because somewhere right now, there are kids going through what I went through. Maybe if they know that I survived, they may find hope in their misery. I can’t say they will ever forget what is happening to them; but if they hold on, they’ll get through and learn to live with bad memories, yet learn to love in spite of them.”

This all happened to Steve. He knows it did. Because every once in a while, in the middle of the night, he wakes up screaming.

THE END

—BY WHIT PRESTON

Steve will next appear in “Love With A Proper Stranger,” a Paramount release.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963

No Comments