Fred Robbins Tapes The Most Candid Interview Ever—With Joanne Woodward

FRED: Hey there, Mrs. Joanne Woodward Newman.

JOANNE: Hey. That sounds so southern.

FRED: You want to get back to New York, don’t you?

JOANNE: Yes, I do.

FRED: What don’t you like about California?

JOANNE: It’s what I love about New York, not what I don’t like about California. California’s fine, if you like California. I happen to like New York.

FRED: You like that house in Connecticut, don’t you?

JOANNE: Yes. The beautiful house in Connecticut. It was a carriage house; it’s two hundred years old, and it’s been added on to—all sorts of funny little rooms. It’s not big, but it’s got room enough for us and all five children. And we once figured out that we could sleep seventeen people, with a little crowding. And it’s heaven; it has a stream in the back yard and a tree house and a swimming pool.

FRED: What’s your two-year-old daughter like?

JOANNE: Oh, she’s not two; she’s three and a half. I think she’s going to be a poetess; she’s rather Edna St. Vincent Millay. She’s very sensitive and very ladylike, and she doesn’t really like to be dirty. Of course, that really sort of unnerves me. I think, what does that mean? Maybe she has some kind of trauma or something? But she’s entirely different for instance, from the younger child: Lizzie is almost like a boy. I think she thinks she is a boy. She beats everybody up, and runs around. A lovely child.

FRED: It’s fascinating, isn’t it, to see two children from the same family, completely different.

JOANNE: Well, we have five from the same family and they’re all different. None of them are alike.

FRED: What are Paul’s other children like?

JOANNE: Well, Scottie, who is the only boy, is bright, intelligent, interested in mathematics, anything to do with his hands—woodwork, and he’s also taking karate lessons and at twelve can break a board with his hands. Have you ever seen that? It’s pretty frightening. Susan is ten, and she is Lolita. She is so beautiful and so grown up that I can’t believe she’s only ten years old. Steffie is a tomboy. She’s all over the place, and all knees and arms now. We don’t quite know what she’s going to be like.

FRED: How often does he get a chance to see them?

JOANNE: Oh, they’re usually with us every weekend, and for a month in the summer.

FRED: The kids get along real great, all of them?

JOANNE: Well, as well, I suppose, as in any large family. They’re marvelous with the babies, with the two younger ones. They’re just great with them, as built-in baby-sitters.

FRED: It’s funny how it all works out, isn’t it, when there are children from another family.

JOANNE: I think the children make the adjustment much better than the grown-ups. I didn’t realize, until I had children of my own, how bright children are, and how sensitive they are.

FRED: I want to get kind of a portrait of this wonderful marriage between Joanne Woodward and Paul Newman, between two really successful people, who have a healthy, as normal as possible, married life in an artistic world.

JOANNE: Well, I think first of all you have to know, and make the decision in the beginning what you want, and what is the most important. In our instance, Paul’s career is most important, in terms of career; our marriage is the most important, I think, for the both of us, and our children; and the fact that we want to be with our children. We don’t want to leave them, and we don’t want to leave each other.

I just turned down a picture that I wanted to do very much, because it was being done in London; and Paul, of course, would have nothing to do in London; but he would go with me, of course. But I suddenly had visions of him sitting there, for three months, with nothing to do, and no go-cart tracks. You know, if he couldn’t go go-carting once a week, he’d go out of his mind. So, I thought, I can’t do that. I said I cannot impose that on my husband. It’s all right if he imposes it on me; that’s fine. I think I have a rather southern attitude about that. I don’t mind sitting around, as I have often done—well, not often, but one long location, when we were on “Exodus;” and I sat for four months with him in Cyprus, and actually I loved it. But Paul doesn’t like to sit around; and it’s not a man’s place. A man needs, you know, to be working, and to be supporting his family.

FRED: Jo, you mentioned go-carting. This sounds like—there are a lot of nutty things that you do together.

JOANNE: Well, actually, the go-carting is not something we do together; this is something Paul does with the children. And I mean all of them, or at least the four oldest ones. Nel, at three and a half, gets on that go-cart with Daddy and is screaming “Faster, faster!” around the track. Have you ever seen a go-cart? You know what they are? And the older children, of course, love them. Scottie, the boy, has a little go-cart of his own. But I just stand by and watch.

We don’t do that many things together, in terms of sports. Because I’m not athletic. The things that we do together that we enjoy are things like antique hunting and walking in New York; taking trips up to Vermont and New Hampshire, going skiing—or Paul skis; I sit by the fire and I wait for him to come home.

FRED: Is he a good skier?

JOANNE: Yes. He’s a good skier. He really doesn’t ski properly, but he’s very good at it. He always is, at all sports, no matter what it is.

FRED: I can testify to that. Remember when we were in Jamaica together, and he amazed me with his ability at tennis, having not played in many years.

JOANNE: Well, he never really played. He never really learned how. In fact, he’s about to take it up again. I’m about to become a tennis widow.

FRED: Who are your friends, Joanne? Whom do you see most of the time, when you’re home in Connecticut?

JOANNE: In Connecticut? Well, the person we see most of the time is my closest friend, James Costigan, who is a writer, and who lives in Wilton, which is just ten minutes away. That was one reason we bought the house in Westport.

And, in New York, Gore Vidal and Howard Austin, who are both very close friends of ours, and Rip Torn and Geraldine Page, and Lee Strasberg and Paula Strasberg and Susan Strasberg. We’re really great loners, though; we don’t see that many people, that often. We actually see more people out in California, I think, than we do in New York.

FRED: Jo, we were talking about this wonderful life that you and Paul are enjoying wherever you make pictures. And then you look at a Liz Taylor, for example, and the kind of life that she’s had. How do you look on a person who’s raised in that artificial world and somehow never got out of it. and is therefore the victim of that artificiality. Would you say that’s about the right analysis?

JOANNE: I would say so. And I think the only feeling that you can have is one of compassion, which I’m sure that Elizabeth Taylor would probably resent no end; but that is how I would feel about it, because it has no sense of reality. And I hesitate to think what would ever happen to anyone like Elizabeth Taylor or someone else who is in the same position, if suddenly they had to be faced with an enormous reality. How would they then cope with it? It would be very difficult, I would think.

FRED: Is that because she has been raised in the cocoon of moviedom, and never been exposed to reality?

JOANNE: I would assume so, because she’s been a star since she’s a child. It’s interesting, though, when you compare the two. I watch television with my little girls, and they had, you know, all the Shirley Temple movies on, which I enjoyed infinitely as much now as I did when I was their age. But isn’t it interesting that Shirley Temple, who was raised in the same kind of atmosphere—in fact, even more so, I should think—grew up to be a normal, attractive woman, who married and had children, and—seemingly, I don’t know her, but—it seems that she lives a quiet, calm life. Perhaps it also has to do with the individual.

FRED: Maybe if Liz had given up her career at that point, before she was an adult—she’d have the same thing.

JOANNE: Well, perhaps if she had done what Shirley Temple did, or what her mother, I presume, very wisely did—as I recalled she stopped making motion pictures when she was twelve or thirteen, didn’t she? And went to school. And had some kind of normal young girlhood. Perhaps if Elizabeth Taylor had done that, and had some kind of exposure to what the world is like outside of the movie studio, that would have been different. Unfortunately, she never did, because she was so ravishingly beautiful.

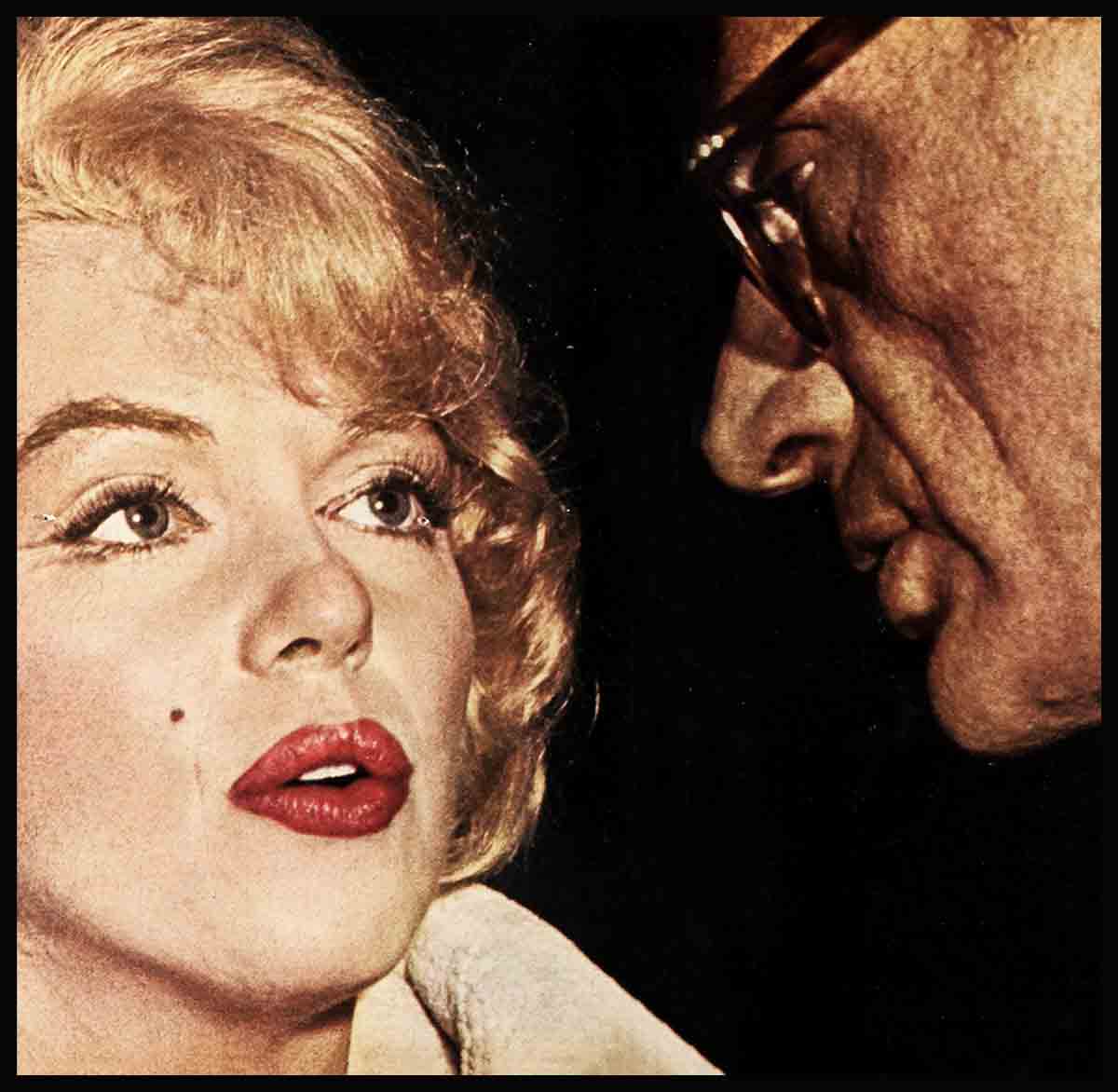

FRED: The same principle, I think, held with Marilyn Monroe, who never could face the real world.

JOANNE: I don’t think it’s really the same principle, because Marilyn was exposed to the real world, in a horrifying fashion, for many, many years before she became the legend that she was. But can you imagine that kind of a contrast from the background that she came from? And the poverty and the unhappiness, to have then been catapulted into just the opposite direction. It must have been a great deal to have been able to cope with. I’m sure that there must have been other problems. I’m talking off the top of my head, because I didn’t know Marilyn, except as a nodding acquaintance, and I know Liz very slightly. So, it’s only a supposition.

FRED: How do you cope with fame?

JOANNE: Well, I think there are certain adjustments that Paul and I don’t have to face as much as other people perhaps, because we lead a fairly cloistered life anyway; and, because we live in New York, the reaction is not the same, often, as it is if you live elsewhere. It always comes as somewhat of a shock to f me when we are recognized, because fortunately no one ever recognizes me. If I’m with Paul, they recognize me. But if I’m by myself, they sometimes look at me as if “That seems to be a familiar face,” but I keep changing my hair, and I play, you know—I play character roles. So there is no identity for them to fasten on to, as there is with Paul.

FRED: How do you think motherhood has changed you?

JOANNE: I think it’s probably made me less involved with my career. Not with acting, because acting I love. But I find now that I’d just as soon do a scene at the Actor’s Studio, or do an off-Broadway play as we’re going to do next year, as do a movie. Because, in the first place, movies take me away from the children too much, and I don’t like it; and they don’t like it. Even the baby resents it very much, when I’m gone all day, and by the time I get home at night the baby is either in bed. or just going to bed. And now I have only an hour with Nel before she has to go to bed. And I tried that hokum of keeping them up late at night; but I realized that you can’t. Children need a certain stability, even if Mommy isn’t there.

FRED: What kind of a father is Paul?

JOANNE: I think he’s a marvelous father. He’s not terribly related to very small children—to babies. But I don’t think most men are, anyway, you know; you have to be a mother to go “go-goo.” But with the older children and with Nel, who’s three and a half, he’s wonderful; because he has enough of the child in him to be able to enjoy them, and yet he is intelligent enough to know that he simply can’t be a companion to them; he must also be a father. It’s a wonderful combination.

FRED: Is Paul moody?

JOANNE: Oh, no. He’s the easiest man in the world to live with. The only trouble is that he wants to stay up all night. And he gets up happy in the morning, which drives me crazy. I do like to stay up late and read; I love to do that. But on the other hand, when I wake up in the morning nobody should speak to me for like an hour, until I wake up. But Paul bounces out of bed, all smiles. And it’s the only time when I want to kill him.

FRED: He’s interested, as I know you are too, in world happenings.

JOANNE: I think we both feel that here is little Joanne Woodward from Greenville, S.C., and little Paulie Newman, from Cleveland, Ohio; and what are we doing here? And that gives you a sense of responsibility. If you have so much, then you have to do as much to deserve it, for other people. Paul even more so than I; he is vitally interested in politics, in the U.N.; he works with several committees at the United Nations, and of course is always flying off to the Phillipines or something to do a person-to-person show, which, even though I miss him. I wouldn’t have him not do it for the world. I’m glad he feels that way; and he is the one who has made me feel that way.

FRED: How can people say that actors have no voice in politics? It concerns everyone.

JOANNE: And not only does it concern every single person on earth, but who has a better right than an actor, who can make himself heard? What better right than to say what he feels? He has a right; he’s a citizen. But there is still a large element of people, in this country, particularly, who have a feeling that actors really aren’t citizens; they’re sort of like children, who should be kept away from everything. But actors are thinking human beings. It’s a tough business, as you know; you have to be a thinking human being to survive in it.

Paul has had this argument with many, many people, because he feels very strongly about his political feelings and about his feelings about the world, and he expresses them loudly, and sometimes vehemently.

FRED: You play a hard-bitten kind of a fashion designer in “New Kind of Love.”

JOANNE: Yes, with glasses and a short haircut and everything, who suddenly pretends that she’s the French lady of the evening. Well—I don’t know if you can say French, because my accent is something other than French; I don’t know what it is. Maybe a little Yiddish. It’s a little Eva Gabor, is what it really is.

FRED: It’s a great kick when you can close yourself in two different roles.

JOANNE: As long as I can close myself in a role it’s fine; when I have to play straight, I’m in serious difficulty.

FRED: Is it because you’re not happy with yourself? Or you’re happier being somebody else?

JOANNE: To me, acting has always meant being something else. I don’t understand the whole theory of finding a personality and playing only that, which is fine if you can do it. I never really manage to achieve that. Besides, I don’t think it would be any fun. I would rather play as many different kinds of parts as I can find.

FRED: Do you like working with him?

JOANNE: Yes, and no. He is inclined to stand off-camera and say, “Honey, hold your chin up; hold your chin up.” And this is a little unnerving. Other than that, it’s marvelous, because he is the hardest-working actor I know. And I am inclined to be lazy—but not around him.

FRED: I hear you tear up quite a storm, Joanne, in “The Stripper.” I’ve heard it’s a very exciting thing.

JOANNE: Oh, it’s a marvelous part; that is, I think it will probably be one of my favorite parts that I’ve ever played, because it’s the first time I ever got to sing, or dance—although I have a feeling that some of my dancing got cut out. Unfortunately, Mr. Zanuck didn’t feel that I danced that well. But the picture itself is, I think, pretty good.

FRED: I read somewhere that Paul got jealous during that picture—some kind of a love scene going on. Is that true?

JOANNE: (Laughs) With Bob Weber. Yes, well, that was—I hope he was kidding, although he kept saying that he felt that Bob was holding on to me much too long, and he kept throwing dirt at us off-camera. He wasn’t very happy about it. What he really didn’t like was the striptease, because I had to do a strip number, and he sat and watched the entire thing, fuming.

FRED: It must be funny to watch your wife strip for—not just the camera, but just potentially millions of people.

JOANNE: It must have felt funny, because he sure didn’t like it. But I couldn’t do the same to him; I couldn’t bear to go on the set and watch him, you know, making love to somebody else. I would hate it.

FRED: It must tear you apart.

JOANNE: I don’t know if it tears me apart, but it’s irritating. So, I don’t watch.

FRED: Gee, to watch your wife doing a strip. That’s a weird feeling, you know.

JOANNE: You’re beginning to think about it.

FRED: Millions of people are going to see you, you know; but on the other hand, look at the pride he could show.

JOANNE: I don’t think he looked at it that way, somehow. I should have reminded him of that.

—THE END

Joanne is in “The Stripper,” for 20th. and Paramount’s “A New Kind Of Love.” Fred’s “Assignment Hollywood” is heard on coast-to-coast radio. In the New York area, you can hear “Robbins’ Nest,” over station WNEW, on Sundays. 8 to 12 P.M.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1963

zoritoler imol

3 Ağustos 2023Hi there, I found your site via Google while looking for a related topic, your website came up, it looks good. I’ve bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.