The Magic Of Love—Cliff Robertson & Cynthia Stone

was a nip in the air that afternoon in late summer. A few dry leaves floated from the lacy trees along New York’s East River, hinting of fall. A family of sea gulls swooped down on the water, picking up billsfull of crumbs and soaring high again. It was a good day to be alive, thought Cynthia Lemmon Robertson, as she gazed across the water, and pulled her sweater closer around her. The sun felt good. She was happy—happier than she could ever remember being. She was in love, and loved.

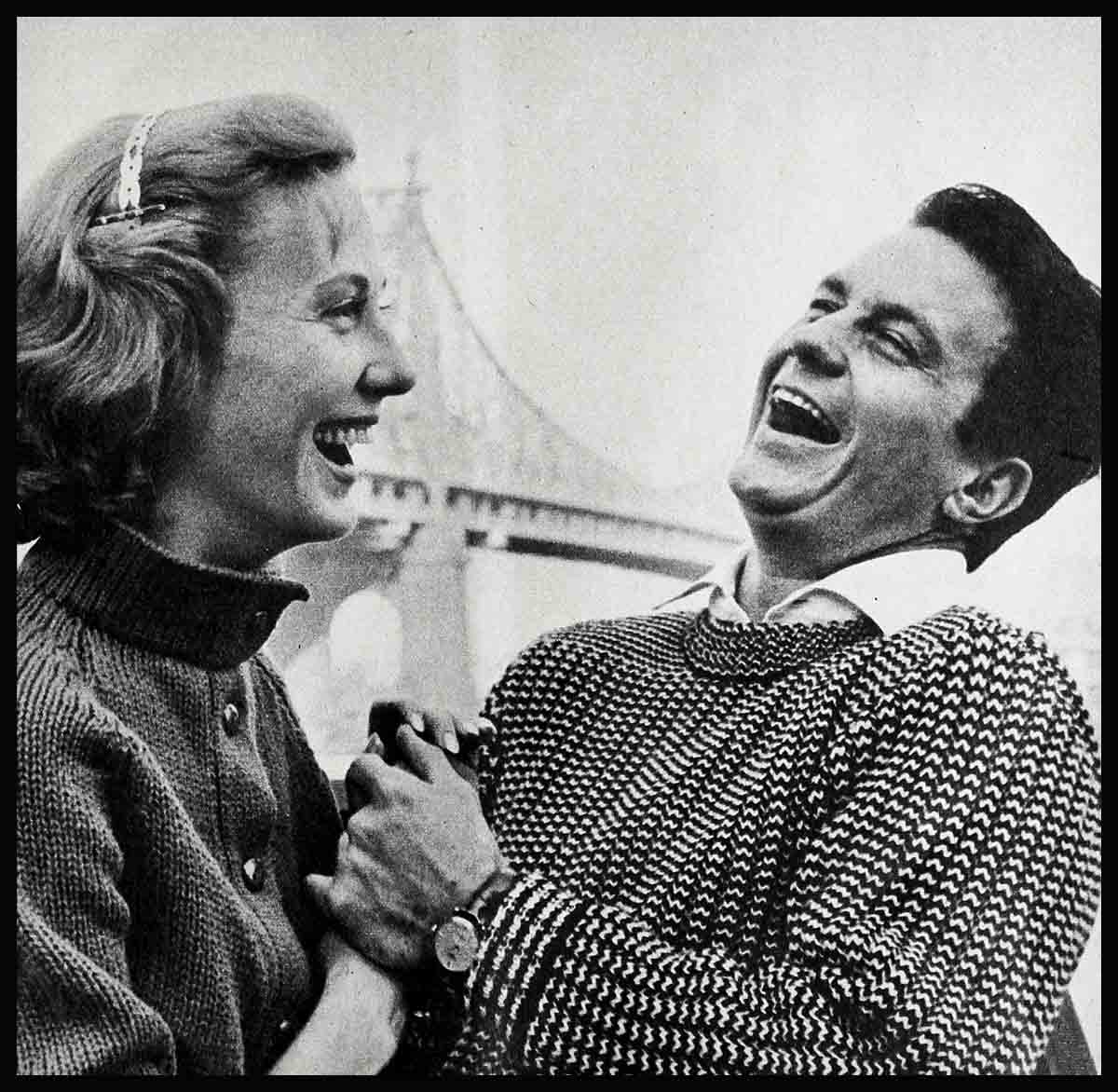

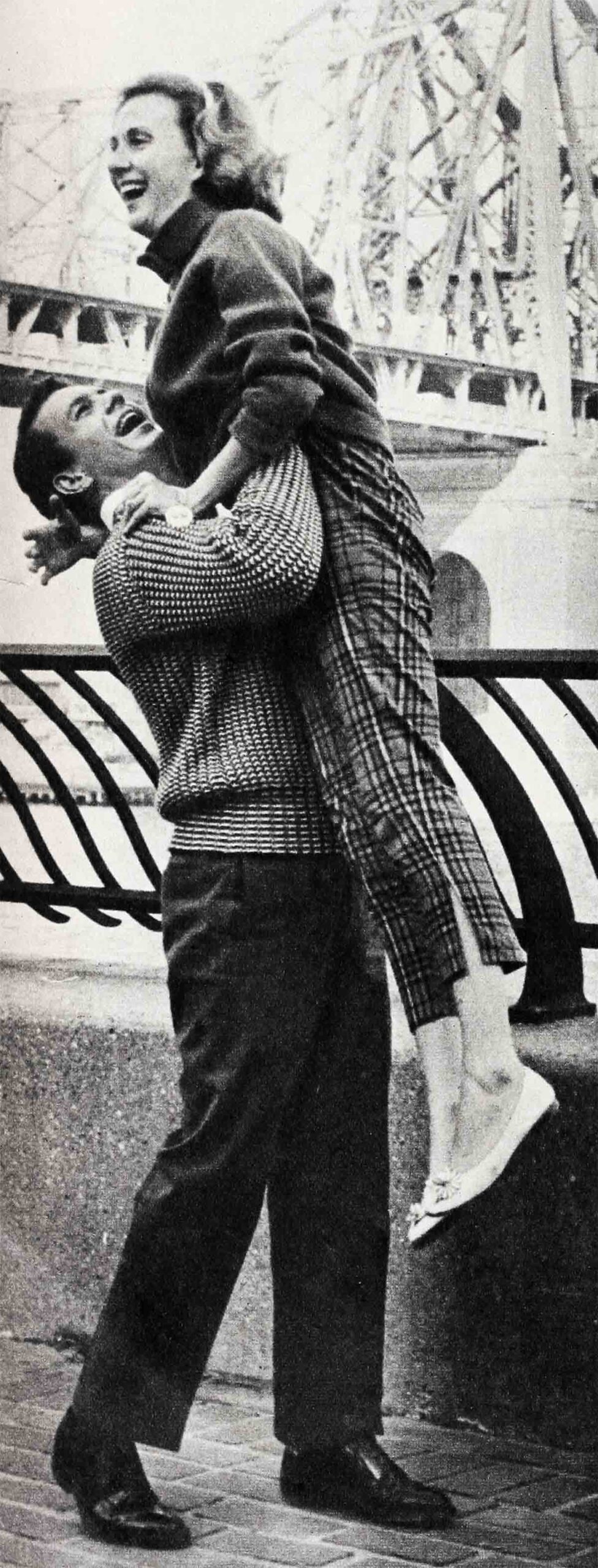

She laughed as she watched her husband, Cliff, a few feet away, trying hard to balance himself as he walked along a bench. She watched his boyish face and lanky frame for a moment—and then suddenly rushed over to him. Jumping down, Cliff ran to meet her, gathering her in his arms for a bear hug.

“I’ll bet I do a better job of bench-balancing than you!” she cried, breaking away and jumping up on the bench herself. Stealthily, and with concentration, she scaled the narrow structure, leaning to one side and then the other, half a dozen times, amid Cliffs chidings and her own gales of breathless, girlish laughter at her success.

They felt like children again, playing along the river after school, the chill breeze toying at their warm sweaters and tingling cheeks. There was a feeling of completeness, of fulfillment, and for the first time in years, Cynthia and Cliff forgot themselves, and thought only of each other.

Life had not always been so full for Cynthia. Nor for Cliff. Cynthia and Jack Lemmon had been divorced in December, 1956, after six and a half years of marriage, and an eight-month separation. On splitting, the couple had announced to a surprised press that the break was no sudden step. “We’d parted once before, before we had come to Hollywood. We’re happier apart,” they felt. Calmly and intelligently, Jack announced, “We just haven’t been able to get along together, and we thought this would be best for our child . . . There is no thought of reconciliation. There is no other man and no other woman—just two people who can’t get along.” And filmdom, although saddened at the breakup of one of Hollywood’s seemingly happy young couples, respected Jack’s forthrightness.

Cynthia was admired for obtaining a quiet divorce without hoopla dramatics, or even a word of condemnation. “It was simply a matter of incompatibility in some personal respects,” she says. “Believe me, Jack never ceased to be the sweet, simple, sincere, decent guy he was when I married him almost seven years ago. He never ‘went Hollywood’ in the slightest, as some folks have unkindly hinted. I respected him throughout our marriage, and I respect him now. I know he loves our boy, and he can see him whenever he wishes. Cliff and I consider Jack our good friend, and we hope for his happiness. He will always be welcomed in our house.”

And Cliff? Thirty-two, a New Yorker from La Jolla, California, a dedicated actor struggling, angling for success, Cliff knew life and he knew himself. He was lonely—and the first to admit it. But he once said, “I think it would be fatal for me to marry just because of loneliness.” He knew himself well enough to recognize that beneath a cheerful, warm, outgoing facade, he was a complex, self-absorbed individual.

Cliff, like every man, knew what his memories were. His restlessness and career drive stemmed from childhood—a childhood it still hurts to remember, for Cliff never knew his parents. He had no memory of either his mother or father; both having died when he was two. His grandmother raised him, along with two of his orphaned cousins.

“Though that home in La Jolla was a good home,” he remembers, “and Grandmother was a kind and conscientious woman who gave me affection and attention and worked to support us, I missed my mother—even though I never knew her. Other kids would talk about theirs. After school I’d sometimes be invited over to their houses, and there would always be a mother there, waiting, with cookies and milk. On Saturdays other kids would talk about baseball games with their fathers, and swimming and fishing trips. I used to hate to listen. Whenever the kids came to our house, my grandmother treated us all kindly, but it wasn’t the same. She felt my need, too, and it hurt her. A boy needs his own mother, for the thousand comforts and consolations that only she can give. The apron string to grab when tumbling off the seesaw, the hand to hold when you’re frightened. At least, these are the things I longed for.”

Cliff longed for a Dad, too, and this has left a void that perhaps nothing can ever fill. “A kid needs a father for the guidance, advice and emotional bolstering, the kind of assurance that only identification with a male parent can give. A Pop who pretends not to see your tears after a fight with the kids next door, but instead takes you through the ropes and shows you a few grips and defenses for next time.

“I remember how I felt as high school graduation approached. I began wondering ‘Who am I?’ With no mother and no father for guidance, where was I headed? While the other kids talked about and planned for college in the fall, I sat on the sidelines and listened. I didn’t dare even think about college. How could I ask my grandmother to send me, I had no place. I was sixteen, but instead of beginning to feel adult, I felt like a rejected kid.”

In search of a “home,” Cliff joined the Merchant Marine and went to sea. He was happy in the camaraderie he discovered, the buddies with whom he shared good times and confidences. Even during the dangers of invasion landings in the Mediterranean and Pacific, the hazards were offset by the closeness and group spirit that he had never known before, a feeling of belonging which he missed after leaving the service, and found himself wandering from one nondescript, menial job to another, back into a life of aloneness.

Cliff can talk about those days with calm and understanding today, half as though they belonged to someone else. “Love is a strange, fragile, illusive thing,” he will explain. “When you find it, so much is opened up. I was twenty-two . . . when I met Becky. She was young and gay and warm, and suddenly I found an entirely new world and began to understand myself a little, began to understand what I was looking for. There’s something touching about a young love. It seems to hold so much purpose and meaning. Becky held all this for me. I loved her with all my heart, as only a twenty-two-year-old can. She did, too, I’m sure. We were never married, though. A few months before the wedding, she died. I’d felt for so long—until Cynthia—that I’d never find love again.

“I was ready for marriage—a man can’t live a life without sharing. I looked, too. It wasn’t that I didn’t give. But, watching fate weave in and out of lives and seeing marriages collapse or compromise—well . . .

“After Becky’s death, I went on to New York. I found a small apartment, a little hideaway on a back street in Greenwich Village near the piers. I could listen to the lapping sound of the sea, and yet, feel the vitality of the city. New York is a magnificent city.” Cliff suddenly stopped talking. “It’s my home. Here I found the beginnings of myself, an identification. I learned I wanted to be an actor.

“Ah, let me say in the beginning, an actor’s life is not an easy one. Casting directors don’t have hearts of gold. How can they? And office girls in casting offices! They know how to make an actor cool his heels. And don’t think television directors are easily impressed. ‘Okay, so you’re a good-looking kid,’ they’d say. ‘So what? Good-looking kids, in New York, are a dime a dozen.’

“Actors Studio helped me a lot. I was grateful to be accepted,” Cliff explained. “And I don’t run around in a T-shirt either! Little by little, with TV jobs and classes, I developed an understanding of acting, and what’s so important, a better understanding of life. I suddenly made friends and I began to crawl out of my shell. Once an orphan, not necessarily always an orphan. I began to be able to recognize this.

“I’m no overnight success, believe me,” Cliff explained further. “Getting the role in ‘Picnic,’ was great but a lot of street-pounding and dreary hours in casting offices went into it.”

To Columbia, Cliff’s performance in “Picnic” was promising and they immediately signed him to a contract (strangely, Jack Lemmon and he are Columbia’s two biggest male stars) and put him opposite Joan Crawford in “Autumn Leaves.” Unfortunately, pictures they’d planned for Cliff failed to materialize and, with the long periods of inactivity, Cliff frequently, these past months, has felt itchy about his career.

It was Broadway finally, not Hollywood, that gave him his biggest challenge. Early this year, he played in Tennessee Williams’ “Orpheus Descending,” to brilliant reviews. (“Cliff Robertson is superb—handome, manly, modest and clear,” enthused the New York Times drama critic, while the Journal-American praised Cliff as “a most prepossessing young actor, who handles the role of the migrant charmer with assurance and vigor.”) The play folded after only two months on the boards.

In the meantime, fans were howling: “When are we going to see Cliff Robertson?” The cry still goes on, but unfortunately, because of distribution changes, RKO’s “The Girl Most Likely” has been kept off the nation’s screens for a year. Cliff had banked heavily on the film, and even though Columbia’s added two more years to his contract, “these past series of events,” says Cliff, “are hardly the ideal climate for proposing marriage. And on top of that I took a loss on salary to the studio in exchange for permission to do ‘Orpheus Descending.’ ” Columbia recently broke Cliff’s streak of bad luck by signing him to portray Van Heflin’s son in “Gunman’s Walk.” “And most important,” Cliff added, suddenly smiling, “I did get Cynthia.”

“Those rumors aren’t correct,” said Cliff, “that I stole Jack Lemmon’s wife. The gossip’s really unfair. Jack and I had been friendly, but honest, I never knew Cynthia beyond the hello-how-are-you stage until after their breakup.”

“I knew Cliff for years,” Cynthia seriously explained, “but only as a good actor and one of Jack’s co-workers. I never really knew him until this past spring. It was early spring and I was visiting some friends in New York, just vacationing, shopping, and taking in the shows. One afternoon, I tried for a matinee performance of ‘Orpheus Descending,’ and luckily was able to get a ticket. I thoroughly enjoyed the play and Cliff’s performance, so afterwards, I went backstage just to say hello and congratulate him.”

“More out of politeness,” Cliff teases, “I invited Cinnie for coffee. Somehow, in the cozy seclusion of an off-Broadway coffee shop, we found a common warmth and understanding. I asked Cinnie to have dinner with me the following night—and, you see what happened, she insisted upon doing it every night.

“I’d been searching for someone like Cinnie, someone who’d put up with me. Who’d be there when I needed her, but who would also possess the intelligence—I guess you’d call it that—the subtlety and wisdom to kind of leave me alone at certain times. So I could feel I was growing on my own. I’d been running wild on the range, bucking like a bronco for almost three decades, I knew I was kind of a patience killer. I was hoping I could find someone who’d accept me as I am and let me be myself in certain ways. No reformer—you understand, don’t you?”

Cynthia, a former actress herself, understands Cliff’s drive. “She’s right for him,” said an old acting buddy of Cliff’s. “Somehow, don’t ask me, you think she’d known him all his life. She’s on the same emotional beam and can talk to him about his career like a Dutch uncle, giving him reassurance when he needs it and recognition in ways that help him most.”

“It’s not so strange that Cynthia can deal successfully with a guy as complex as Cliff,” a friend of Cynthia’s explained during their small, intimate wedding (so quiet that the press hardly got wind of it). “She’s got a good head and strong shoulders. She knows the pitfalls of marriage and is determined to avoid them on her second try. She puts a lot into what she does and you can bet she’s going to give their marriage everything she has. Cynthia’s one girl who can understand sorrow and loneliness and make Cliff a family.”

“I’ve got a perfect family—a catalogue family,” Cliff laughs heartily. “Just like shopping in a Sears book. A tall, blonde, beautiful wife. A lovely home, impeccably decorated. A small, impish, loving new son. All, with only a big fat down-payment of happiness.” A world to share. No longer “the strange one” set apart from other children, struggling through adolescence and manhood to find his own private world. He once said: “Being without parents, feeling oneself an orphan, it’s like being the scissored-out center of a paper. It’s just a void, a nothingness. A child’s need is only fulfilled by the mirror of love and approval held up to him by his parents. The satisfaction or denial of that need is like the difference between darkness and sunlight.”

Today, that darkness has become sunlight and that sunlight is Cynthia. Today, a brisk walk in the park, a nippy Sunday afternoon outdoors; a silly joke, a private embrace: all these are the things Cliff’s world is made of, bringing warmth and happiness for they’re brought by the wonderful, elusive, magic of love. Cliff Robertson never asked for more, not even as a boy, for he knew only this was worth wanting and waiting for.

Recalling a very favorite childhood story, Cliff told us recently, “Once upon a time, there were three little boys. They were good boys and the good fairy offered to each of them one wish. ‘You have only one, she cautioned, ‘so consider your choice very seriously.’ Without a moment’s hesitation, the first little boy raised his hand. ‘I want fame,’ he said. The second little boy quickly raised his hand, too. ‘I want money,’ he answered. But the third child, shier and more retiring than the others, hesitated long and seriously, then slowly gave to the fairy his answer. ‘I want,’ he said, ‘to be loved.’ That little boy was me.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1957