Hollywood’s Biggest Comeback

Where are the stars of yesteryear? What are they doing now? Did their wealth and fame bring them happiness? These are the questions everyone is asking, for the wonderful personalities of the past are returning again to the dizzy heights of their heyday. Every night, they’ve been coming into your living room, through the old movies being shown on TV, to cast their spell again. Last month, we began their great story—the ‘biggest story in Hollywood today.

Did they find happiness? For some, the answer is, “Yes.” For others, “Maybe.” And in some cases, it must be, “No.” But read on, and come to your own conclusions:

Look at Myrna Loy—green-eyed, red-haired, freckle-faced Myrna started off in films as a siren, Oriental variety. Whenever there was any fancy slithering to be done, or somebody’s husband to be undone, that was Myrna’s department. However, when sound came in, Myrna the Menace was on her way out. The makeup crew could make her look like evil incarnate, and Myrna’s slim sleekness took care of the slinking. But her voice was strictly from Montana (Raidersburg, to be precise), as endearingly plain as her real last name (Williams).

Two studios dropped her before M-G-M took the gamble and tried her as a normal American woman. The try-out worked just fine, and the studio really hit the jackpot when William Powell joined forces with Myrna to create those zany sophisticates of Nick and Nora Charles, in “The Thin Man.” This hatched a series that eventually stretched out to six. Meanwhile, Myrna was working up a reputation as the screen’s “perfect wife.” In “Test Pilot,” for instance, Clark Gable went on a whale of a bender from one end of the country to the other. Upon his return home, chastened and bloodshot, did he find Myrna waiting with a shotgun? Don’t be silly. She was there with love and understanding and sympathy and—well, you get the idea.

In 1951, the “perfect wife” wed her fourth husband, State Department aide Howland Sargeant, whom she met while she was a delegate to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. There were two more films, and then last year she scotched retirement rumors by plaintively querying, “Why can’t an actress join an organization like UNESCO without having the world say she has retired? I was only waiting for a smart, sophisticated comedy, and I found it in ‘The Ambassador’s Daughter.’ ” The public disagreed on the film’s quality. And there matters stood—until Myrna’s old films showed what a fine talent had been sitting around wasted. Since, especially for TV, Myrna has filmed a series tentatively titled “Her Majesty.”

William Powell and Myrna Loy costarred so frequently that periodic statements were ‘issued to keep the public from confusing their movie and their private lives. Off-camera, Bill has been happily married for seventeen years to Diana Lewis, a starlet with whom he eloped on two weeks’ acquaintance. Rarely seen in new films these past ten years, Bill has a ready explanation for Photoplay’s readers.

“I realized I had to face old Father Time, so I did ‘Life With Father.’ That was a character role, and it turned out pretty well.” (It won him the New York Critics’ Prize.) “So I began to cast about for more mature roles. But movies don’t come up with many parts for an actor of my age. I’m too far along to carry romantic roles. Besides, moviegoers don’t want to see old goats like me as lovers. But I’ll come back for good roles if I can find them.”

Hollywood, there’s your cue! Nationwide statistics on TV showings of the “Thin Man” films and “The Great Ziegfeld” (“more stars than there are in heaven’) indicate that the Powell charm is of the ageless sort. And, as Lonesome George would say, “You can’t hardly get that kind no more.”

Bill’s good friend Ronald Colman (Hollywood’s “Three Musketeers” once were Powell, Colman and Richard Barthelmess) is another selective critter. Unless he can do something really good, he’d rather do nothing at all. Recently recovered from a lung ailment induced by pneumonia, Colman has the lead role in Warners’ current all-star spectacle “The Story of Mankind.” Unlike Clark Gable, who let out a blast last year when M-G-M began releasing its film library to TV, Colman feels the video revivals are a good thing.

“As long as a film has exhausted its theatre potential,” the veteran star tells us, “I see no reason why it shouldn’t be shown. Besides, it keeps one’s name and work before the public.” Have the showing of Colman’s old films affected his relations with friends and neighbors in any way? “No—except for favorable comments now and then, and occasional comparisons with TV pictures of today.” From the always-tactful Colman, there is no elaboration on that last point. And what does he now think about movie-making in the old days? “Well, it was more fun perhaps—and less tension. But then, of course, one was younger!”

A couple of femme favorites who have been selective to the vanishing point in recent years are Claudette Colbert and Irene Dunne. Claudette, who has done three unremarkable films since 1951’s dramatic “Three Came Home,” was all set for her own TV series not too long ago; but her husband, Dr. Joel Pressman, nixed the idea on health grounds—didn’t like what he’d heard about the strain from Hollywood actresses working on TV. It was also about this time that Claudette let loose a blast at the skimpiness of gowns on home screens.

“I call them bathtub dresses,” she said. “The girls look exactly as if they’re sitting in a bathtub. A lot of times the camera cuts you off right here”—pointing to her chest—“so you don’t see a thing but white shoulders. And a lot of those shoulders don’t look good! I guess some girls don’t care what they look like as long as they’re showing some flesh!”

Claudette has always been candor itself, but this particular bit of oratory has its humorous side: Claudette got her own movie start in a bathtub! C. B. DeMille was looking for someone to play the Empress Poppaea in “The Sign of the Cross.” The actress had to convey the idea that she reveled in taking milk baths. Claudette was tagged it. Later, she served DeMille as a memorable Cleopatra, and went on to win an Oscar for the historic free-for-all “It Happened One Night.” That was the night the Santa Fe Railroad held up the Super Chief. Claudette was all set to board the train when the Academy telephoned her with the glad news she’d won an Oscar. They held up the train, while Claudette went to collect her prize.

Many another fine Colbert performance followed, and a lot more of them will be seen when Paramount and Universal, the last two holdouts, iron out their current TV feature-film deals. Meanwhile, Claudette has contented herself with occasional appearances in TV spectaculars and other shows, summer-stock work and a stint replacing Margaret Sullavan in a Broadway play. Recently she exclaimed, “I’ve been out of movies so long that now, when I get into taxis, the drivers want to know why I left pictures. I never left. Will you please tell that to all the people!” Note that all top entertainers enjoy their work—and if honest, admit enjoying acclaim.

Irene Dunne has been seen even less often—and now has a splendid excuse for her show-biz inactivity. President Eisenhower recently appointed her one of five alternate American delegates to the United Nations. This is an honor that Irene has fully earned; but fans, after reviewing her wonderful work in “The Awful Truth,” “Love Affair,” “Penny Serenade” and “I Remember Mama,” will surely clamor to get her back before the cameras. In Hollywood, when scandals break and divorce monopolizes the headlines, Irene is held up as a contrasting example of how to have both fame and a serene private life.

Next July 16th, Irene and her physician husband, Dr. Frank Griffin, will celebrate their thirtieth anniversary. She holds the record for the most Oscar nominations without a win (five). In establishing herself among filmdom’s all-time favorites, she broke most of the rules. When Irene entered Hollywood, sex-pots ruled supreme and gaudy glamour was as plentiful as air.

“It’s not for me,” she told a friend. “That’s one side of it. There’s another. It’s smart to be conservative—if you’re born conservative. I was. I’ll play that way, being myself.” Later, her exceptional personal qualities were to gain her a Notre Dame medal given only to outstanding Roman Catholic laity and an award from the National Council of Christians and Jews. The title of “Hollywood’s perfect lady” was repeated often enough to be embarrassing. “It’s nice of people to call me a lady,” she once remarked. “But I do hope they’ll remember it’s important to be a woman first.”

A fellow conservative, Claude Rains is another who’s made himself scarce. He’s one of the few players able to hold their own before a camera with Bette Davis.

Though he played some sympathetic roles, Claude is best remembered for the parts he once referred to, with relish, as his “dirty dogs.” (In “Anthony Adverse,” “Adventures of Robin Hood,” “Notorious,” etc.) A hayseed at heart, London-born Claude struggled for success in the role of a private-life American farmer. He now lives on 300 acres in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, along with chickens, pigs and bushels of corn. About forty Rains films are now available for TV, and you can see him “live” shortly (as the villain, natch!) in the TV spectacular “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.”

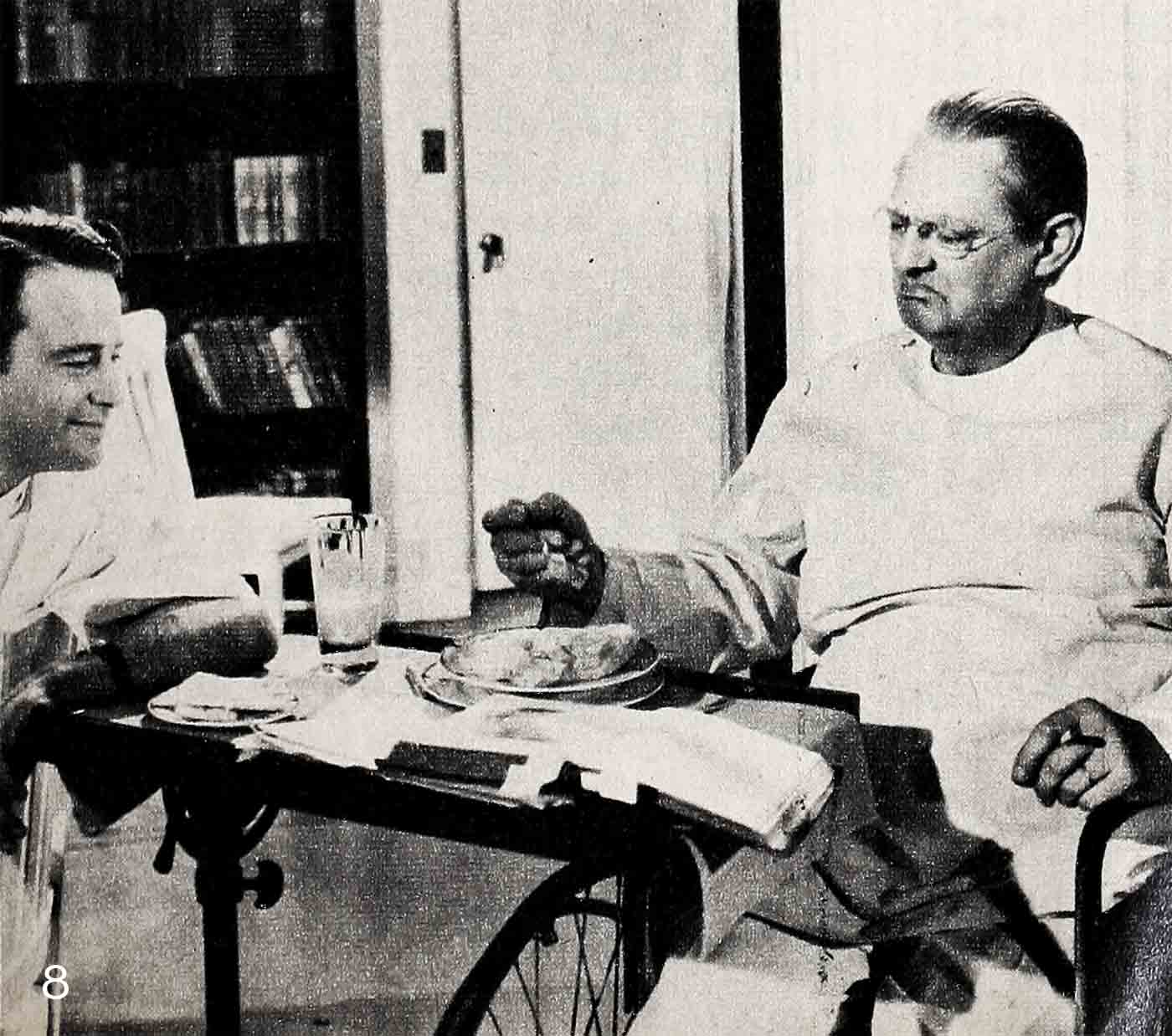

The actor having probably the greatest TV revival (twice weekly in some communities) is the late Lionel Barrymore (1878-1954), an astonishingly versatile person and, while he lived, a testament to the human spirit in the face of adversity. Until twenty years ago, Lionel had distinguished himself in several plays, acted in scores of movies (he started in 1912), written a number of screenplays, directed six films and won an Oscar. Then he acted in “Saratoga,” which seems to have been bad news for its cast. Star Jean Harlow died before it was finished, and a hip injury that Lionel sustained on the set confined him to a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Far from ending his career, he spread out in new directions. Ahead of him lay the Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespieseries, in which, as the crusty old autocrat of Blair General Hospital, he endeared himself to millions. On the side, he was painter, novelist and composer of symphonic music. Lionel’s death reduced the big three of the acting Royal Family to one. Sister Ethel, like Lionel an Oscar-winner, is now in semi-retirement and was recently on your theatre screens in “Johnny Trouble.”

Mention of the Barrymores brings up the Bennetts, another family of theatrical renown. At the head of it stood Richard Bennett, a magnificent actor and a flamboyant personality. Asked once if daughter Constance inherited her temperament from him, Bennett shot back, “Now where the hell do you think she got it from?” He was intensely proud of all three daughters and their success. Barbara retired early from the game, and Connie went along her own spectacular way, at one time becoming the highest-salaried player in pictures. But it was the relatively subdued Joan who proved to have what it takes over the long haul. “You can never tell about Joan,” her father remarked during her youth. “She has all kinds of possibilities.”

Those possibilities never really came to light until producer Walter Wanger cast her as a neurotic in “Private Worlds.” He then prevailed upon her to let her blondined locks revert to their natural dark brown shade. This step improved her screen image and brought out a marked resemblance to another Wanger protégée, Hedy Lamarr. The idea was given an added fillip when Gene Markey, Joan’s second husband, went on to become Hedy’s second husband.

Anyway, in 1940 Joan eloped with her producer. They had two daughters, to add to Joan’s two daughters by her previous marriages. In films like “Woman in the Window,” “Scarlet Street” and “The Macomber Affair,” Joan projected her popular personality plus plenty of pulchritude, and many of her hits are now in the TV treasury.

The rarity of Joan’s screen work these days may be traced to the time, twenty years ago, when she subbed for a pregnant Margaret Sullavan in the road company of “Stage Door” and promised herself time out from films for footlights. In recent years, she’s been quite successfully active in theater work all over the country.

The other lady that Wanger brought to stardom is Hedy Lamarr, often called “the most beautiful woman in the world.” Oddly enough, it’s for this reason that Hedy probably won’t be watching her old films on TV in Houston, Texas, where she and her fifth husband, oil millionaire W. Howard Lee, make their home.

Hedy has always been of two minds about her famous face. A close friend once observed, “She clings to the idealization of her beauty—it’s the one thing she has that is her own that she can be sure of.” But Hedy frankly blamed her classic features for a lonely life and a dismal marital record.

Husband number one, munitions magnate Fritz Mandl, shut her up in a castle while he made futile attempts to buy up all prints of “Ecstasy”—that torrid bit of German celluloid wherein Hedy went swimming in nothing but water. The seventeen-year-old bride took her cloistered existence for almost five years, and then fled to America. After a dazzling debut in “Algiers” (“Come wiz me to ze Casbah,” murmured Charles’ Boyer), Hedy’s Hollywood future was assured, and she soon embarked on her second marital venture. This was with Gene Markey, who, Hedy testified at the divorce, spent exactly four nights in fourteen months at home with her. Husband number three was actor John Loder. For number four, bandleader Ted Stauffer, Hedy put all her possessions on the auction block and moved to Mexico. That idyl was over in seven months.

Now Hedy is at U-I making “The Female Animal.” When all is said and done, after seeing her recently, the Lamarr beauty is still one of the fabulous sights of this generation.

Merle Oberon is another lovely who’s had more than her share of private woes. Discoverer Korda claimed she had “the most beautiful face I ever saw,” but when Merle came to America, producer Samuel Goldwyn told her to “go wash it” (i.e., take off the exotic makeup). She did, and scored in a string of hits. (Her personal favorite is “Wuthering Heights.”) A very regular gal beneath her aristocratic film manner, Merle was probably happiest entertaining troops during World War II. But private happiness eluded her.

Korda was knighted three years after their 1939 nuptials, and Merle mixed in London society as his lady. Divorce ended that union in 1945. Then an allergy to sulfa drugs left her face scarred. (The scars were later removed.) Merle and movie photographer Lucien Ballard married by proxy in a 1945 Mexican civil ceremony. The marriage was over in 1949. Some months later, Merle watched her Italian admirer, Count Cini, crash his private plane in flames before her horrified eyes. “My life is finished,” she wept. “There is no point in going on.”

She seemed to move aimlessly in international circles, doing occasional TV work and sitting pretty much on the sidelines, though she was often heard to say, “Things are calm, calm the way I’ve always wanted them.” Last summer, she wed wealthy Mexican industrialist Bruno Pagliai, and present indications are that Merle’s long battle for private happiness is finally won.

Another kind of battle, on a lighter level, was fought by Dorothy Lamour vs. her sarong. “I’ve worn a sarong in only six pictures,” she once confided, “but the public thinks I live in one.” Dottie’s persistent efforts to part company with her Polynesian wrap-around were doomed to failure. During the war, servicemen stationed in the South Seas wrote in regularly to complain that “Nothing here looks like Dorothy Lamour.”

Dottie later left the film tropics, quit stooging for Hope and Crosby and appeared in some well-dressed roles with indifferent success. The payoff, however, happened at the London Palladium a few years ago.

Dottie came onstage in two yards of silver lamé surrounded by 104 yards of billowy white tulle. As she went into her first number, a balcony voice inquired, “Where’s your sarong?” Dottie went on singing, and the inquiry was repeated. She motioned the orchestra to stop, and replied, “I’ll see what I can do.” After a ninety-second dim-out, the lights came up and the tulle had vanished. The applause that followed must have rattled teacups around the country.

Dottie currently spends some time on her highly successful night-club act. More often, she’s home with husband Bill Howard and their two boys, Johnny and Tommy. The kids may sit up to watch Mama’s early jungle epics—but Dottie doesn’t. She’s had enough of that sarong!

Sonja Henie’s films are also now available for TV. Shrewd businesswoman Sonja, once listed among filmdom’s ten femme millionaires, still goes out every year with her ice show and plays to standing-room only. In private life, she is now married to a fellow Norwegian, shipping tycoon Niels Onstad.

She won her first Olympic championship in 1928, at the age of thirteen. (“Everybody is always wondering how old I am, and I keep telling them, ‘Don’t figure back.’ They do, though.”) A few scenes later, Sonja was in pictures. The formula for Henie films was always a handsome leading man (Don Ameche, Ty Power or John Payne), a minimum of story and dialogue and a maximum of ice—and it clicked every time. Among athletes turned film stars, no one has ever matched Sonja’s fabulous success, though Esther Williams probably came closest. Between films, Sonja was smart enough to go out and be seen in person.

Why keep on skating? “It’s good for my nerves,’ Sonja tells Photoplay. Will she ever make another film? “Well, I’ve never been under any illusions that I’m an actress. But I know I could sell a show. If I could find a story that would use my skating show as background, as ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ used the circus, then I’d do it fast. But until then, I’ll skate along as I am. When I go out on the ice, I feel wonderful. I’m relaxed and I’m happy. And what else matters?”

The opposite of this picture of calm serenity was Sylvia Sidney with heart-shaped face and sad eyes. “I can’t relax in Hollywood,” she would say. “It’s too closely tied up with work for me.” So she’d usually hop a plane or a train for her native New York and stay there between pictures. As a result, she had no close friends in Hollywood, avoided parties (“with millions of people you don’t know”), and few people got to know her at all. But some provocative facts made the rounds: She was fond of gardening and swimming, drank about fifteen cups of coffee per day, chain-smoked alarmingly and kept her hands almost constantly in motion. On set between takes, she could usually be found working off nervous energy by knitting.

Onscreen, she became a specialist in pathos. “Sylvia Sidney and Her Saga of Sadness” headlined one magazine piece, for nobody, but nobody, could throw a weep like Sylvia. “In the pictures I play,” she chirped, “the girl who strays, pays— which provides me with some swell crying scenes.”

Sylvia’s boxoffice rating went to pieces, partly because of poor management. She and Charles Boyer were announced for “Wuthering Heights,” but her boss decided it was “too depressing.” And finally, she herself bowed out of the “Algiers” role that made Hedy Lamarr a star. What was left was effectively demolished by several poor pictures in the Forties. Sylvia never liked Hollywood, and came to have a pronounced preference for stage work.

In these reminiscences of stars who are shining anew on your TV screen, we’ve concentrated mainly on personalities no longer on the Hollywood screen scene. There are many others: Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, who are proving that their wonderful appeal is timeless; the late, great Leslie Howard, with his peerless sensitivity; Greer Garson; Dick Powell, crooner or tough guy; the movies’ most charming child, Shirley Temple; Frank Morgan; Robert Montgomery; Lew Ayres; Wallace Beery; Charles Boyer; Geraldine Fitzgerald, Robert Walker.

To all of them, we owe a debt of gratitude. They have brightened our lives immeasurably. They have entertained us, amused us, touched us, inspired us. And they were able to do this because of the never-ending magic of motion pictures, a magic that only the movie industry can fully instill. This is a magic that is tremendously costly—in terms, not only of the high-priced personalities it employs, but in story and production costs to give these great ones the proper vehicles. For this reason, until pay-as-you-go TV becomes a reality, it will be years before today’s new films are seen on your television screen.

But, when that same magic can come back, to enchant us again and again, when it can preserve forever the best of youth and charm and talent, who can complain?

ANSWERS TO “HOLLYWOOD’S BIGGEST COMEBACK” QUIZ

1. Clark Gable, Claudette Colbert in “It Happened One Night”

2. William Powell, Myrna Loy in “The Thin Man”

3. Tyrone Power, Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice”

4. Fredric March, Joan Bennett in “Trade Winds”

5. Leslie Howard, Merle Oberon in “The Scarlet Pimpernel”

6. Jerome Cowan, Jon Hall, Dorothy Lamour in “The Hurricane”

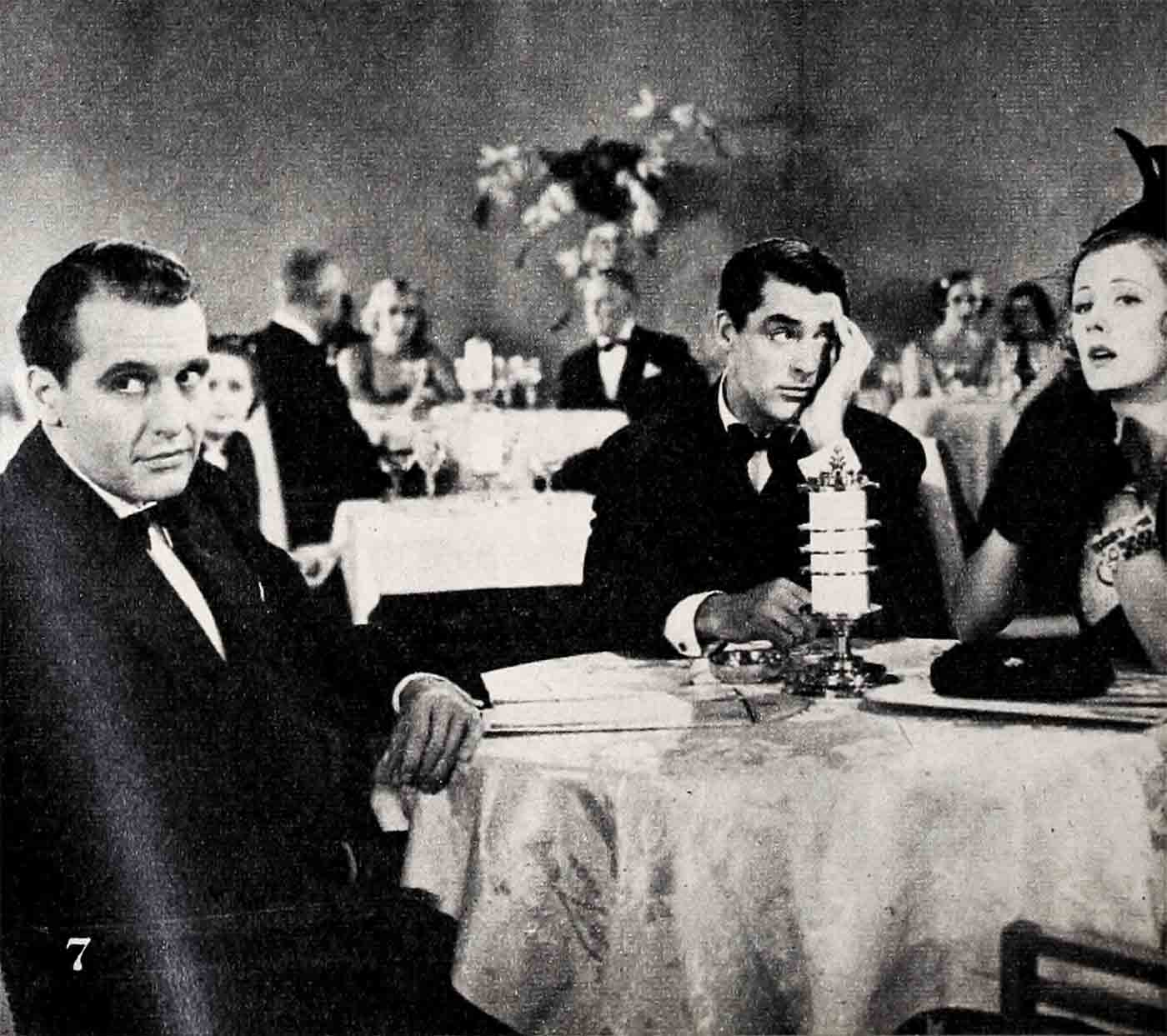

7. Ralph Bellamy, Cary Grant, Irene Dunne in “The Awful Truth”

8. Lew Ayres, Lionel Barrymore in “Dr. Kildare’s Crisis”

9. Sylvia Sidney, Gabriel Dell, Joel McCrea in “Dead End”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957

No Comments