What’s Cary Grant Up To?

Five years ago everyone in Hollywood thought Cary Grant was about to rest on his laurels and fade away into retirement. Today, at fifty-three, he is one of filmdom’s hottest boxoffice personalities.

“I was an idiot, an actor and a bore until I was forty,” says Cary candidly. “I’ve now reached the point in life where I am no longer solely concerned about myself. As a result, I feel I have finally gained self-respect. I admit to my age—fifty-three—because I want to spare people the trouble of leafing through almanacs and old magazines. They’ll get nothing but the wrong information.”

For Cary’s boyish, debonair brand of elegance, the price is steep these days. For acting in “The Pride and the Passion,” he was paid $300,000 and ten percent of the gross. This is his price and producers beg to meet it. He is also in the enviable position of being able to pick his own stories. When Cary finds what he.wants, he calls a producer and says, “I’ve got a story here that is sure-fire. You put up the money and I’ll put up my talent and we’ll split the take.” Producers grab the offer like a bargain.

Since “The Pride and the Passion,” Cary’s made “An Affair to Remember” with Deborah Kerr, the just released “Kiss Them for Me” with Jayne Mansfield and Suzy Parker, and he’s currently doing “Houseboat” with Sophia Loren. (Since Sophia is the highest paid lady actress in the world, this will be a mighty expensive boat ride.) After “Houseboat,” there are at least fifteen more pictures waiting for him when and if he decides he wants to do them. He also has his pick of leading ladies.

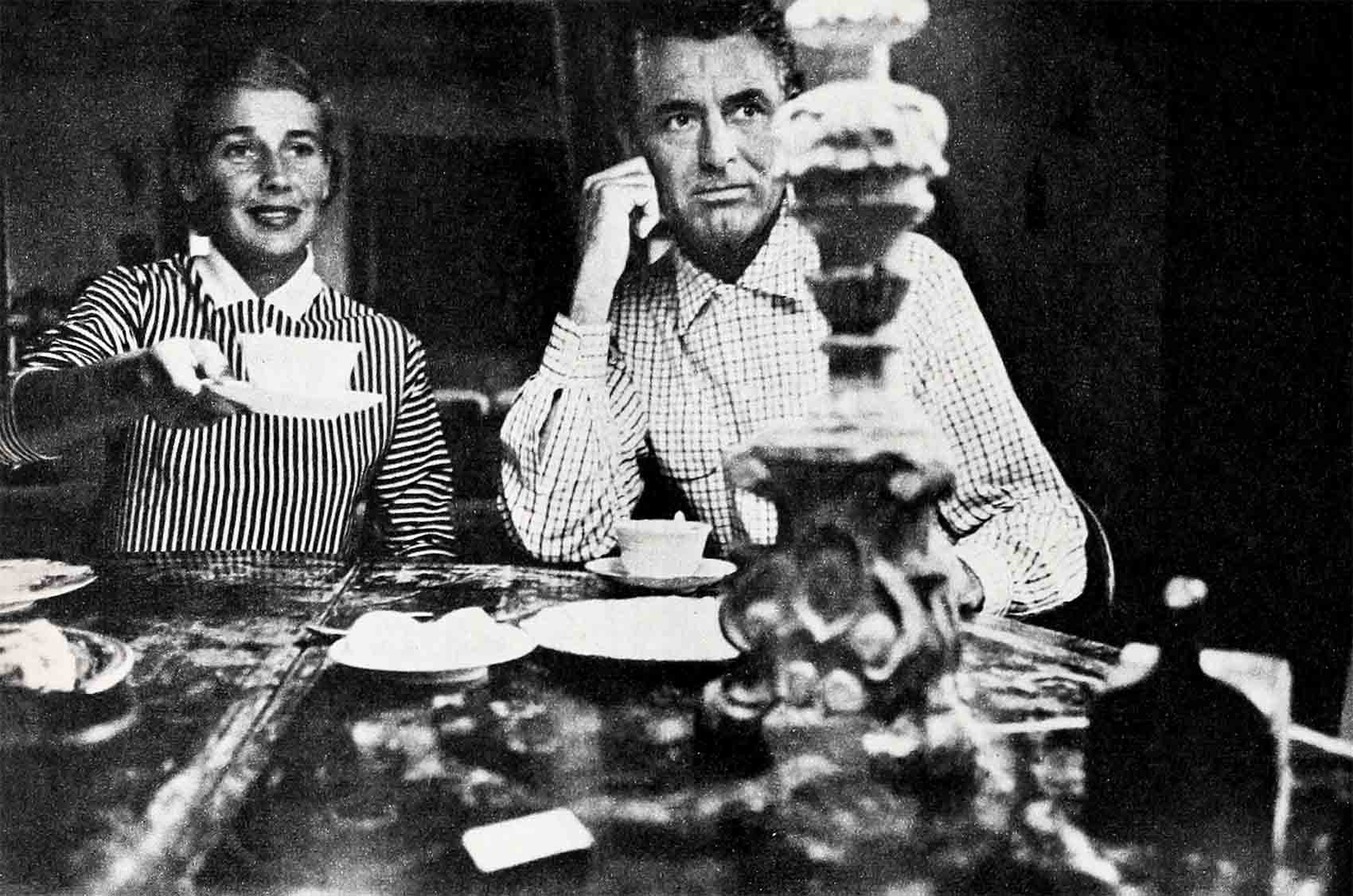

But in spite of the fact that he is a wealthy man, Cary and his actress-writer wife Betsy Drake, live comparatively simple lives. They have a house in Beverly Hills and another in Palm Springs, but neither is pretentious by millionaire standards. The Palm Springs home is the favorite, and there they spend most of their time when they aren’t traveling. While Betsy writes, Cary plays tennis, rides horseback and lolls beside the swimming pool. (“I’m dull; all I do is relax.”)

The Grants shun publicity and are looked upon as a pair of lone wolves. They rarely entertain. An old friend who has known the couple for years says, “I’ve never seen the inside of their house.” Even more rarely do they attend parties. Of Hollywood parties Cary says, “They consist of two groups of people—one set wouldn’t be found dead talking to the other, who in turn wouldn’t be found dead listening to the first.”

And Cary Grant practically wouldn’t be found dead talking about himself. Although he’s been making movies for twenty-five years and has granted hundreds of interviews, the facts about Cary Grant’s personal life are few. Even to friends, he is an enigma. This is not due to any reticence on his part. A man of quick enthusiasms, Cary has theories on a wide range of subjects, and will talk about them at great length—special ways of brushing your teeth, spiders, sports cars, clothes, Buddhism, women and how to cut down on martinis. But he is reluctant to talk about Cary Grant. As a result, he is the source of much speculation and produces varying reactions from people who know and work with him.

For instance, producer Jerry Wald tells an interesting story about Cary. Jerry hates to do cutting of film once a movie is complete. It is a costly operation and may wreck the continuity, he feels. “Recently studio heads swore the running time of the script ‘Kiss Them for Me’ was too long,” relates Jerry. “I disagreed and decided to ask Cary Grant to read it aloud for me. Cary’s fast-paced sense of comedy timing is so perfect that he read it in one hour and forty-seven minutes—and the finished picture clocks in at one forty five! After hearing him, I stuck to my guns and refused to cut the script.”

Incidentally, in explaining the importance of detail in “Kiss Them for Me,” his fifty-sixth film, Cary said: “What actors fail to realize is that when they move a couple of inches before that camera, they jump twenty feet on the Roxy screen.”

From the point of view of columnist Earl Wilson, who spent some time with Grant while he was making “The Pride and the Passion” in Spain, “Cary is one of the kindest people I’ve ever met. The whole time I was with him he didn’t knock a soul. In the case of a successful actor, that’s something.”

On the other hand, a former acquaintance of Cary’s remarked recently, “He’s really a terrible snob. The first thing he does when he meets somebody is check what he’s wearing. If it is not up to his own standards, he will as likely as not walk away.”

The facts are he is kind but more snob than not. He believes in living with a certain amount of grace and dash. He admires elegance and style. He is almost obsessed with neatness and order. And he respects these same virtues in other people.

For instance, Cary is particularly articulate about the Actors Studio influence in shaping recent Hollywood films. (“Is a garbage can any more realistic than Buckingham Palace?”) Need he say more?

In 1953 and 1954, Cary suddenly took a two-year hiatus from the movies and went around the world on a freighter with Betsy. His friends say the reason partly stemmed from what he felt was Hollywood’s morbid preoccupation with the “ashcan” school of drama. According to one insider, “There were a diminishing number of screenplays that fitted Cary’s own highly polished style, and he had no intention of changing it.”

Recently, Cary made this comment on the changing movie scene: “Actually, I’d love to get back to those comedies I used to do. But where can I find one? Writers take themselves too seriously these days. Also, really polished comic dialogue is hard to write. It’s much easier to create crude, everyday speech, and writers make a lot of money doing it.”

But Cary’s self-imposed “retirement” came to an end in 1954. “My old friend Alfred Hitchcock persuaded me to read the script of “To Catch a Thief,” he said. “He told me that if I would play it, he would throw in Grace Kelly for good measure. It was the kind of bright, literate script that appealed to me, and Grace was the well-bred, well-groomed type that I always enjoy playing opposite.” If there was any doubt that Cary Grant’s appeal had faded, this picture completely removed it.

And Cary’s brief appearance on TV a year later, when he received the Oscar for Ingrid Bergman, not only enhanced his own reputation but gave the Awards a dignity which had been lacking up to that moment. As a guest said, “It was the beginning of the comeback of elegance.”

Frank Vincent, once Cary’s agent, also greatly admired his client’s brand of debonair elegance. Shortly before he died, Frank said, “Even though Cary became an American citizen in 1942, he is essentially an Englishman. His home is his castle, the last refuge of his privacy. Marriage to him is a very private affair, and he simply refuses to give out progress reports on his welfare. He never has and as far as I can see, he never will.”

The one “progress report,” made known even to outsiders, concerns the relationship with his wife, Betsy. One of the Grants’ close friends has said, “Betsy has been a stabilizing influence, helping Cary develop a calmer and more mature attitude towards life. She has certainly changed his feelings about women. Until recently Cary had very little regard for them. He was rarely able, for instance, to accept one as a friend.” Cary is quite frank in discussing his relationships with women in the past, and of his ex-wives (Virginia Cherrill and Barbara Hutton), he now says, “I know why they divorced me. I was horrible, loathsome. They were absolutely right.”

His first marriage to Virginia Cherrill in 1934 was a spectacular failure. A charming, witty girl who achieved brief glory as Charlie Chaplin’s leading lady in “City Lights,” she was as unable to cope with Cary’s instability as he was to the whole idea of marriage. Cary, for one thing, was whooping it up with a vengeance at the time. For instance, after one particularly lively evening on the town, he called up several of his friends and the police and announced that he had poisoned himself. The police arrived with a stomach pump, and in spite of Cary’s protestations that it was only a gag, they pumped him dry. His good humor, however, hadn’t forsaken him. Getting to his feet, he said soberly, “Gentlemen, you’ve nearly convinced me never to take a drink again.”

A month later the marriage was officially over.

Cary’s second marriage, to Barbara Hutton in 1942, lasted longer—three years—but could hardly have been termed more successful. It got off to a bad start when snickering gossip writers cattily referred to the match as “Cash and Cary.”

His friends remember Cary at the time as being extremely moody. For days he would be incommunicado. Then, unexpectedly, he would turn up at a party and cheerfully thump away at a piano and sing bawdy songs in a rich Cockney accent. But it was apparent to everybody that he wasn’t happy. No one knew this better than his wife. Barbara said after they were divorced, “Cary never took me out and when we were married I hardly saw him. At night he was always busy with his clippings or the radio.” This odd relationship seemed to bother Cary as much as it did his wife. Barbara recalls that he would often comment bitterly, “I can’t understand why someone like you would marry me.”

All of this changed, his friends say, the day Cary met Betsy Drake.

Cary saw Betsy for the first time in London, where she was playing in the British version of “Deep Are the Roots.” He was impressed by her talent and delighted by her appearance. Aboard ship, on his way home from Europe, he saw her once again strolling along the deck. He was more attracted than ever to this serious girl in her “sensible” flat-heeled shoes. While trying to figure how to manage an introduction, Cary ran across his old friend Merle Oberon, who was also aboard and who knew Betsy. She wangled a pair of seats for them at the captain’s table.

When Betsy and Cary got home, he arranged to have her play the lead opposite him in his next picture and on Christmas Day, 1949, they were married in Arizona, with Howard Hughes as Cary’s best man.

An old friend who had made the rounds with Cary in his carefree between-marriages days said of him recently, “Cary developed a new dimension after marrying Betsy. Up until that time I don’t think he had ever harbored a serious thought in his life, and the only thing he read with much attention were scripts. Betsy opened up for Cary the whole new world of ideas.”

Betsy is given to the same kind of impetuous enthusiasms as her husband, but with her it is nature and metaphysics and Buddhism. “One day I came home to find the house crawling with books on spiders,” recalls Cary. “I glanced through one by a Frenchman named Jean Henri Fabre, and I became fascinated by the little fellows myself. Spent the rest of the day reading about them.” Often Betsy would stagger in with armsful of books on all kinds of meaty subjects, and Cary became as avid a reader as she. “I discovered there was so much I wanted to learn,” he says. “Reading is a refreshing release from the idiocies of life, idiocies I know only too well.”

Hypnotism, for instance, is one of Cary’s favorite topics of conversation these days. From his enthusiasm, one would gather it is almost a cureall for most of the world’s ills. In his own case, he says, it has helped him give up smoking and drinking.

The Grants have an extensive library on the subject of hypnotism and often experiment on each other. One evening, Cary suggested that Betsy use her hypnotic influence to help him give up smoking. “I went to sleep in a trance,” he says, “and when I woke up, I felt perfectly splendid. But automatically, as usual, I reached over to the bed table for a cigarette. I lit it and was nauseated. I haven’t smoked since or wanted to.”

While making “An Affair to Remember,” Cary developed a growth on his forehead. It became so obvious that the producer decided to halt production while Grant went to the hospital. A month or six weeks seemed to be the minimum time it would take Cary to recuperate. “I told him not to stop anything—to shoot around me if necessary—and that I would be back to work in a few days,” explains Cary. “And with a local anesthetic and self-hypnosis as pain killers, the growth was removed in a forty-five minute operation!”

Within a few days the actor was back on the lot. Not only was there no growth; there wasn’t even a scar to show for the operation.

And there is still nothing on Cary that indicates what goes on inside him. These days, as reluctant as ever to talk about himself, Cary is eager to discuss Buddhism, psychiatry, the Atom bomb or yoga. He sums up his feelings like this: “I know people who will go scurrying to their graves without having the slightest idea of what life is all about, without even trying to find out.”

Me old friends who knew Cary when he was content to let others carry the world’s burdens are sometimes dismayed at his solemn declarations about life and the world. But most are pleased and recognize this as a sign of emotional growth.

This change is most apparent in his relationship with Betsy. He is very close to his wife. Whenever he is away he always—her lengthy, intimate letters every day.

The longest time the Grants have been apart is when Cary was in Spain. Finally, Betsy sailed to join him—on the ill-fated Andrea Doria. Cary knew nothing about the ship’s sinking so he was understandably confused when he received a telegram from his wife reading: “ABOARD ILE DE FRANCE. ALL IS WELL. NOT A SCRATCH.” “Later,” he recalls, “from friends’ messages I pieced together the news that the Doria had foundered, and that Betsy had transferred to the French ship.”

Cary frantically called her on the ship’s phone, and a friend who was standing beside him said, “Tears streamed down his cheeks when he finally heard Betsy’s voice and learned she was safe and well.” Betsy suggested that he relax and take his co-star, Sophia Loren, out to dinner. Cary said later, “Betsy is the first wife I’ve had who is also a friend.”

But if he presents a solemn side on occasion it has certainly not dimmed his boyish good humor. In London recently to visit Betsy who was making a movie there, Cary told reporters, “I’ve given up smoking and drinking. Now I can devote all my energy to the only vice I have left—love.”

But he might have two others—his compulsion for work (he starts work this month on “Kind Sir,” in London with Ingrid Bergman, after finishing “Houseboat”) and his obsession for keeping youthful and fit.

“I guess every man looks the way he wants to,” Cary says, “and shapes himself like a sculptor. If you decide you are going to be handsome, youthful and fit for the rest of your life you will be. It’s as simple as that.”

THE END

—BY EDWIN ZITTELL

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1957

graliontorile

11 Ağustos 2023Very interesting details you have noted, thanks for putting up. “Jive Lady Just hang loose blood. She gonna handa your rebound on the med side.” by Airplane.