Is Elvis Presley Quitting For God?

Out of the depths of my soul I cry

Jesus draw nigh, Jesus draw nigh

Lord, lend an ear to my own honest plea

Jesus draw nearer to me.

Oh Lord, I want to labor

Faithful each day, let me walk in Your true way

Telling this old world what a Savior I’ve found

Spreading the Gospel all around.

. . . from an old Gospel song

Elvis was only seven when it happened. It was back in Tupelo, Mississippi, the city where he was born. It was a bad day in the late spring, hot, oven hot, so hot you could smell the heat float up from the dry earth. Elvis was sitting with a buddy of his on the steps of the ramshackle plantation house just outside the city. His buddy’s dad was a poor sharecropper and, like the other sharecroppers who worked the plantation, they were standing around now listening to the old plantation owner yell at them.

“You’re all pickin’ rotten,” the old man said, his voice as gruff and mean as his heart, “all you no good vagrants. I send your stuff to market and they tell me it’s no good. You’re pickin’ rotten.”

“Stuff we’re pickin’s rotten, boss,” one of the men spoke up. It was Elvis’ buddy’s dad. “All over the state it’s like this. Ain’t had no rain for long now and it’s the crops that’s at fault, not us.”

“That’s right,” another voice spoke up.

“That’s right,” all the men cried out.

“You’re all pickin’ rotten,” the old man screamed again, the blood rushing up to his perspiring face. He hobbled down the stairs and over to Elvis’ buddy’s dad. “And you, you vagrant scum,” he growled, “I don’t take no back talk like that from nobody, you understand?” He pointed to the spot where Elvis and the other boy sat. “Go on,” he said, “take your kid and his pipsqueak friend and go back to your shack and tell your wife to start packin’, ’cause you’re leavin’ this plantation, suh, you hear? You’re leavin’ as of right now.”

“You can’t fight God and His workin’s,” the boy’s dad said softly, pointing up to the sky and then walking over to the steps to pick up his son and Elvis and start back to the shack.

“I can fight whoever I goddam please,” they heard the old man shout as they began to walk away. “Goddam weather ruinin’ my crops,” they heard him holler, as suddenly he began running across the field next to the big house, shaking his fist up at Heaven, “. . . goddam old man up there in his big goddam throne, drivin’ me to ruin, not givin’ me any rain and drivin’ me to ruin!”

It all happened so fast and mysterious after that, Elvis thought for a few minutes it was a dream.

It seemed to come from the north, that big black blanket of a cloud. It came low and suddenly and so quickly did it spread itself out above the plantation you would have thought it was being pulled by a thousand invisible horses whose snorting made a big warm wind and whose hooves, slamming hard against the ground, made an awful and steady and ever-loud rumble. Its core and blackest spot followed the old plantation owner as if it had an eye, always directly above him as he continued running across the field, shouting his blasphemies at God, shaking his fist in anger and hate.

And then, from the cloud’s eye it seemed, the stroke of lightning came tumbling to the earth in one fast flash. And when it was gone and the cloud above began to lighten, the old plantation owner was dead.

It was raining, a soft quiet drizzle, when Elvis and the others got to the spot where the old man’s body lay. Stunned and shaking a little, Elvis looked around, first down at the wet contorted body, then up at his buddy’s dad. The sharecropper looked very solemn as he took off his hat and said a little prayer for the dead man, for his soul.

Then, putting his hat back on again, he looked down at Elvis and his son. “There are things in this world you just don’t question,” he said. “Love God. Fear God. And—you’ll see—everything in this here life will be all right.” . . .

The ringing out of The Word of God—the Gospel Singers

All shook up in a new life

Elvis has never forgotten that day. He became a deeply religious boy then and there. And up until only a few years ago his main ambition in life was to become a Gospel singer. The South is full of quartettes who specialize in old-time religious songs—spirituals, Gospel numbers, hymns—and young Elvis would wait all week long for the night his Mom and Dad would take him down to the local church or auditorium to sit for three, four and sometimes five hours, listening to the music, clapping their hands, tapping their feet and, once in a while, feeling the happy spirit to join in the music and with the happy thought that someday Elvis would be up there, too, singing away for God.

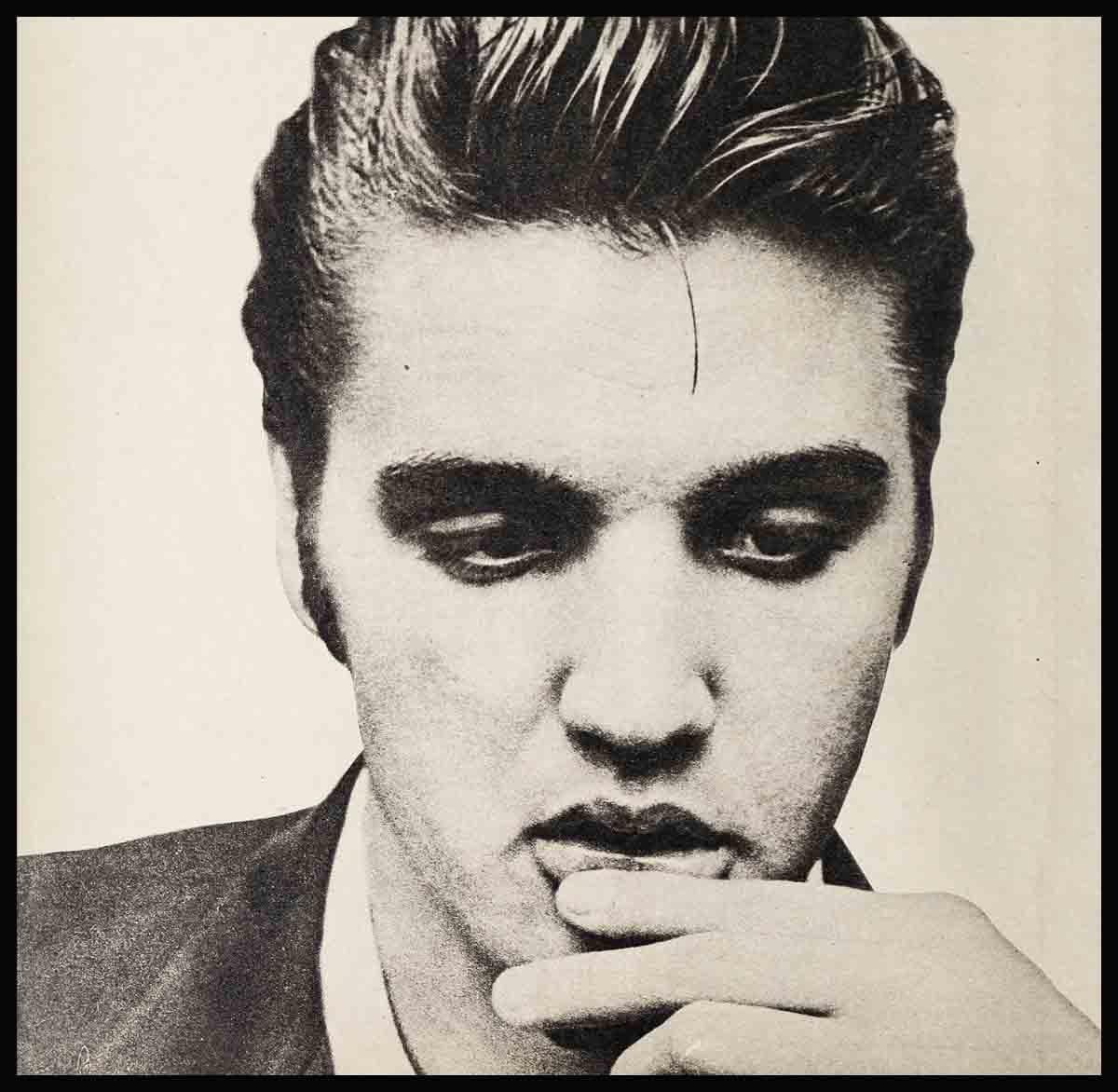

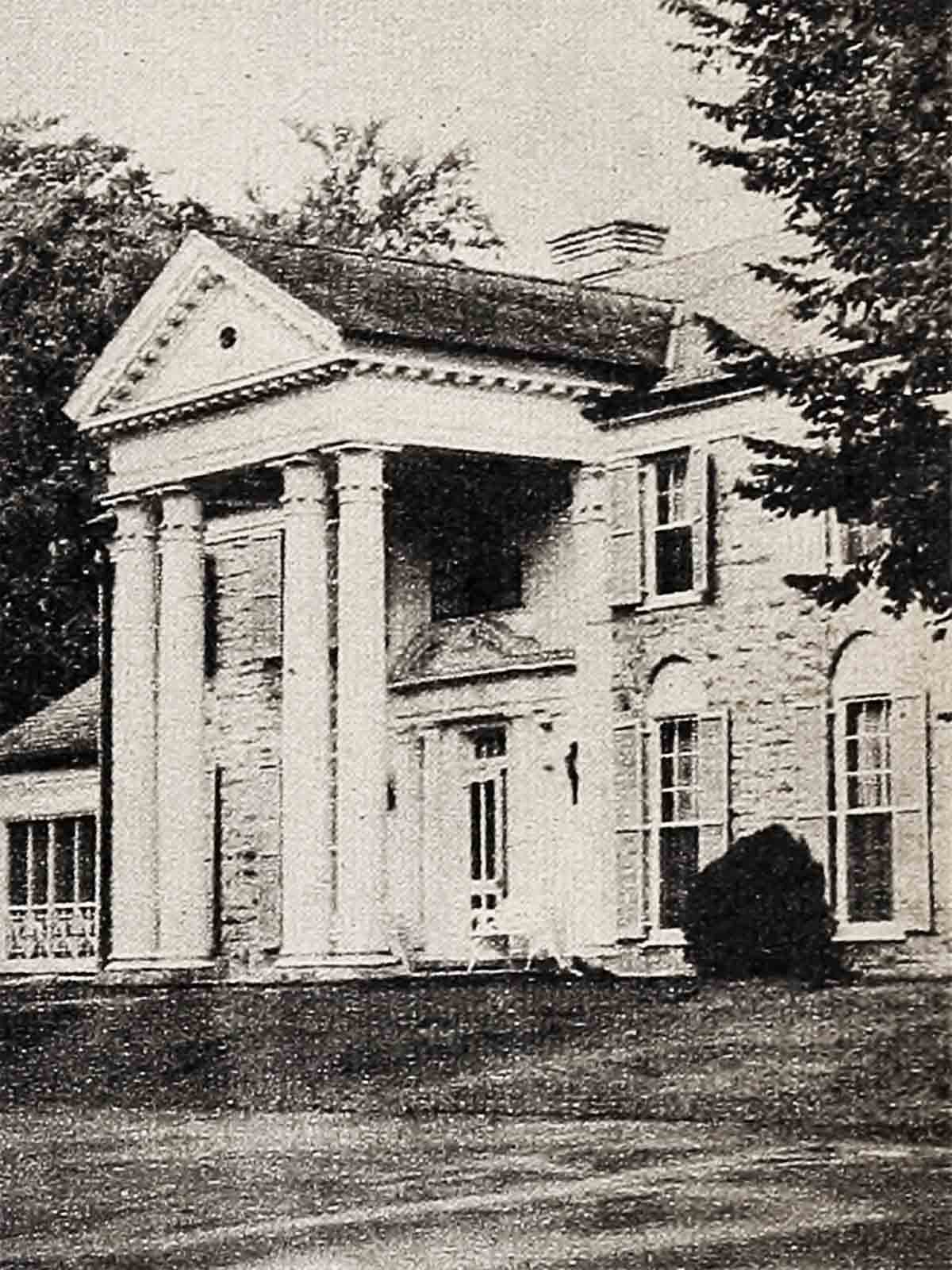

And then, suddenly, Elvis—the poor boy from Tupelo, Mississippi, and then Memphis, Tennessee—became the Elvis Presley we know today; the millionaire rock-and-roller; the boy with everything—with mansion and swimming pool, and more spending money in his pocket at one time than most men earn in a month, and crowds screaming for his autograph, and women weeping to touch him. With tens of millions of people buying his records and going to see his movies and connecting his name with all that is wild, shook up, frantic, hopping in the world today.

Elvis can’t sing

I first heard the story about the old plantation owner from Elvis himself a couple of years ago, when he was just beginning to climb to the top. I wondered recently how the climb had affected the strong religious feeling he’d gotten at the time, how it had affected his early ambitions to travel around the Southland singing songs of Jesus and Heaven and The Good Life in the Hereafter.

I decided to ask. Elvis was in Memphis, vacationing with his folks at the time, and I went down to talk to him and to some of the other people in town who knew him.

When I returned to New York, it was with some astounding news. Not only was Elvis still deeply religious, but there seemed to be a strong possibility that he might quit show business and the big money someday soon and devote the rest of his life to Gospel singing and to the service of God!

The idea was first hinted at by the Reverend James E. Hamill, pastor of the church Elvis frequently attends, the FIRST ASSEMBLY OF GOD. Reverend Hamill—a powertully-built, soft-spoken, extremely popular man, just recently returned from three months in Europe where he headed a Gospel team for three months—began 24 telling about Elvis when he first knew him.

“He must have been about thirteen years old at the time,” the Reverend said. “He’d just moved to Memphis with his family from Mississippi—where I was born, too, by the way—and the family lived not far from our house. Elvis, being about the same age as my son Jim, became friendly with our boy and was with him quite a bit of the time. I remember him as quiet, so quiet that sometimes you didn’t even know he was around. And I remember that he always needed a haircut and that he was a good, courteous boy who joined our Sunday School from the beginning, attended regularly and acquitted himself well.

“He had a great interest in Gospel singing, I remember too, and it must have been only a couple of years after he got poe that he tried out for the quartette my son had been singing in. It was a good quartette, so good that they had a spot on one of our radio stations every day. Well, one day one of the boys had to drop out. When Elvis heard about this he came running over to my Jim and asked him if he could join. He’d been practicing a lot and he didn’t think he had too bad a voice, he said, and he’d do anything to be able to sing with the others. Jim told him all right, he could try out—but he’d have to pass an audition first. The audition, I remember, was held right here at the church. very carefully done, as if it were a tryout for the NATIONAL BROADCASTING COMPANY or some such organization. When it was all over, my Jim and the other two boys shook their head and told Elvis they were sorry, but they didn’t think he was quite good enough for their quartette. ‘Elvis, you can’t sing, they told him, ‘you’d better give it up altogether.’ Of course, after what has happened to Elvis, all you have to do to send my Jim into conniptions is to say to him ‘Elvis, you can’t sing!’

The casual Elvis

“Anyway, Elvis has become very popular. And I like the fact that he is still the courteous boy he always was and that, when he comes back to Memphis, he always drops by to pay me a visit and talk things out. Id like to say right here and now that I do not endorse nor subscribe to rock-and-roll. To me its a throwback on paganism. And also it is very dull as music. And, while I realize it isn’t for me to judge people’s tastes, I do not like it, nor do I think it is particularly upbuilding to the morals of our youth. And I would like to state emphatically, contrary to some things I’ve seen in print, that Elvis did not learn what is described as the beat of this type of music by singing in this church.

“But enough of that for now . . . What I think is important is that Elvis is a religious boy and that he does come here, right to this room, right to that chair you’re sitting on now, to talk things over with me. And so casual, Elvis is—it’s a pleasure to talk to him. Im a rather tense person myself, so I enjoy it doubly to see his what’s the hurry attitude as he sits there, for an hour and a half sometimes, chatting about anything that might be on his mind.

“Yes, he’s a good boy, Elvis is,” reverend said.

Will rock-and-roll last?

And then, suddenly, with a knowing and satisfied smile, he continued:

“And it makes me feel good to know that he’s really not too happy in this rock-and-roll, that he will give it up along with movies and other things within a year or two, that he will devote his life to something of greater worth.”

I asked the reverend if, by this, he meant that Elvis might turn back to his first love, Gospel singing.

The reverend thought for a moment. He shook his head. “I can say nothing more at this time,” he said, “. . . except that I think he will give it all up.”

The seed had been planted now.

I investigated further.

He talked next to a buddy of Elvis’, a fellow about Elvis’ age who works for the singer, along with three or four other boys, as companion, bodyguard, friend and what-have-you. “I’ve never talked to Elvis about it direct,” he told me, “but sometimes I wouldn’t be surprised if, after Elvis comes out of the army, he’ll feel he’s had enough of this world of fast cars and big houses and everything and go back to what I know he’s always wanted to do, Gospel singing.

“You know, here at the big house, with all its fancy trappings and its automatic gate down there on the roadway and its play cellar with its wall-to-wall carpeting, lots of people get the impression that Elvis has a ball here every night with his pals, and with some pretty girls we invite over. Well, it’s true that El does sleep most of the day and stay up most of the night. And it’s true that there’s usually a small crowd of his friends here. But it ain’t true what you hear about, the wild parties and the crazy screaming and yelling and people pushing each other into the pool with all their clothes on, all that stuff. You know what usually goes on? First, there’s always a nice dinner that El’s Ma makes. And then everybody goes downstairs if it’s cool or out near the pool if it’s not and we put on records and dance. And then, after that, El gets out his guitar and if somebody’s there for the first time, like this girl from Hollywood, I’ll never forget, she’ll think, Oh boy, now we get to hear some rock-and-roll from the master’s voice. But what El actually does is to spend the whole rest of the night singing all these songs he’s known ever since he was a little bitty kid, Gospel songs he learned at the revivals and in church and at all the religious meetings he used to go to.

His folks can’t go to church

“I’ll tell you another thing, too. Maybe I shouldn’t say it. I don’t know. Anyway, if you do print this, don’t put my name down as having said it. But I know for a fact that El feels very bad about his Mom and his Dad not going to church anymore as much as they used to. It ain’t that they’re any less religious than they ever were. That ain’t it, at all. But, you see, they’re shy people, Mr. and Mrs. Presley are, people who were always used to being poor and unimportant. And now with all this publicity El’s been getting they can’t make a move anyplace, especially here in Memphis, without a hundred people pointing at them and looking at them like they were something from outer space. And this makes them uncomfortable and even more shy. And so, because the same thing has happened to them in church, they’ve kind of stopped going as much as they used to. And I’ve heard El talk to them about this. And I’ve seen him look real depressed about it. And one day, when I know he was thinking about this, I heard him say, ‘How is God gonna know you love Him if you don’t show up at His House for a little while, just the way you expect Him to keep showin’ up at yours?’ ”

Elvis muses

The third person I talked to was an old woman, crippled now with arthritis, but who till recently worked for Elvis and his folks. “That Mr. Presley,” she said, referring to Elvis, “he is a chosed boy of God. Else why he have so much good fortune right now? Yes, the good fortune is mostly material and financial. But you mind me, Mr. Presley is going to repay the good Lord one day, repay Him with the voice God gave him and by singing His songs to the people, to all the people of the land.

“He believes in God very strongly, Mr. Presley does. Why when I was over there working for them, it used to hurt me so much to read stories in some magazines about what a little devil he was when it came to women and high living and all that nonsense. Because all that time there he was in the same house with me and I’d see him, such a wonderful boy, usually sitting by himself, in that big chair he favored near the window, just resting and looking out at the garden and the trees and some of the flowers that his daddy had planted a few months before he came home.

“Once, I recall, he was sitting there with a magazine on his lap, looking out of the window, with a kind of a certain look of sadness in his eyes. And I said to him, ‘What’s the matter, Mr. Presley? You been reading another one of those stories about yourself you don’t like?’ He shook his head and smiled and said no. that wasn’t it; he’d just been reading something about science and things like that, he said, about a whole bunch of men who were working on a rocket to go up to the moon. ‘You know,’ he said to me, after thinking a little while more, ‘I don’t understand these people who are trying to find ways to go to Mars and the moon. I believe that the moon was put there to light up the earth and not for people to try and go up and see what it’s made of.’

“And another time, when he was sitting there, that look in his eyes again, I said to him, ‘Mr. Presley, it’s getting to be such a nice night out tonight. Why don’t you go out and have yourself a nice time with some of your friends?’ And you know what he said to me? He said, ‘I can’t go anywheres now, ma’am. I’m sitting here praying. I don’t pray as much as I should, I guess. But every once in a while I’ve got to sit still for a while and thank God for the blessings of giving me a good Mom and a good Dad and for making me healthy and for giving me a job that time way back when my Dad was sick and couldn’t work and things looked so dark for us. Every once in a while I’ve got to talk to God like this and thank Him . . . and ask Him what He really intends for me to do in the long run of my life.’

“You ask me, man, do I think it’s silly—the idea of Mr. Presley someday turning his whole attention to God and singing those songs of Jesus he loves so much? No, I don’t think it’s silly. Matter of fact, from those deep dark mysterious things I’ve seen in Mr. Presley’s dark mysterious eyes when he’s talked about religion and sung religious songs for me, I’d be surprised if he didn’t.”

THE END

—BY CLAIRE WILLIAMS

You can see Elvis in MGM’s JAILHOUSE ROCK.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1956