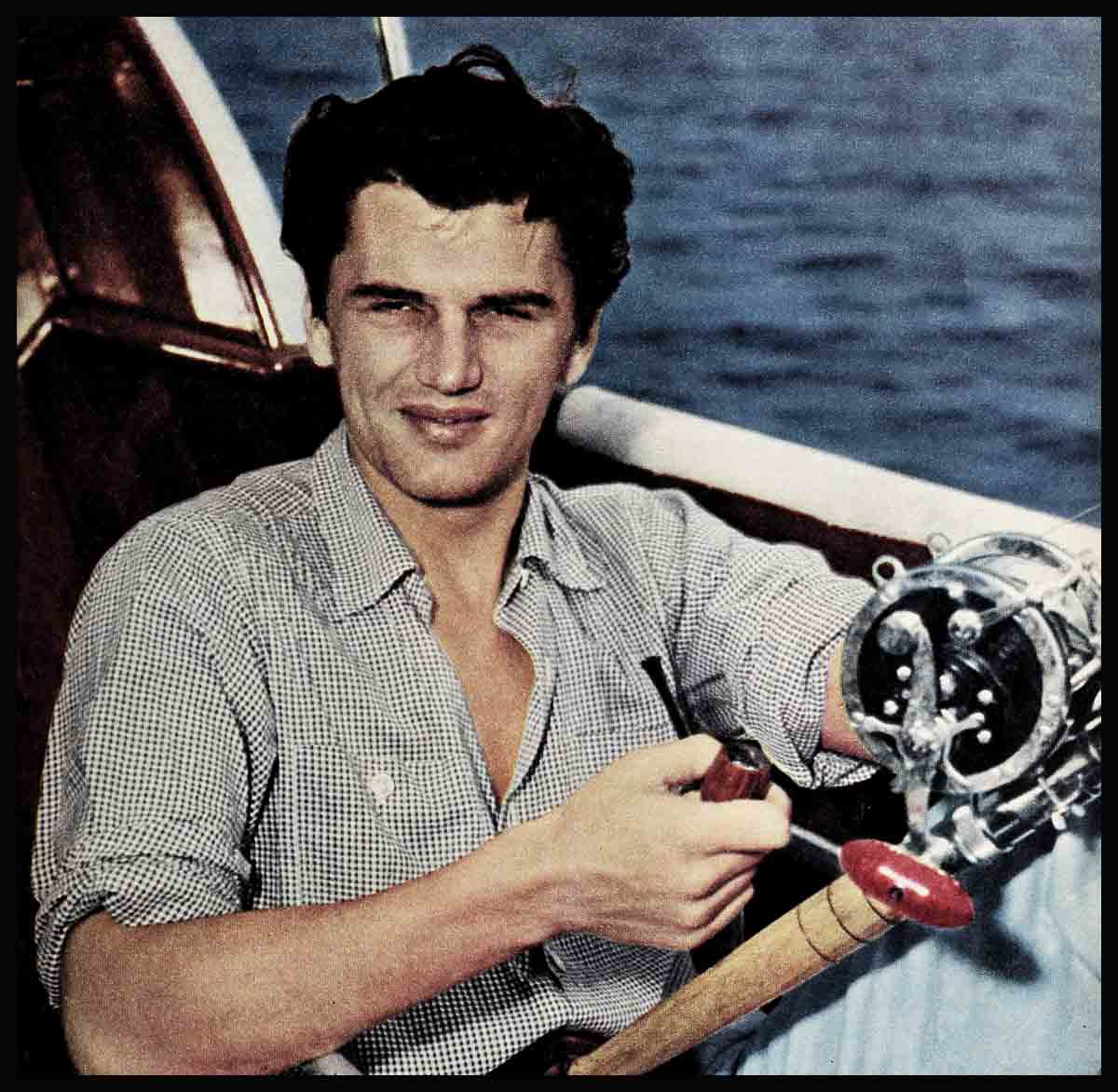

Edmund Purdom—Man On A Tightrope

Excitement and tension were high—not only with the fans who watched from outside Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, but to the hundreds of famous “fans” who waited expectantly in the lobby and inside the theatre. The premiere of “The Egyptian” was a big one—even by Hollywood standards. It was a big picture and an important one. And if those pre-premiere rumors were correct, it was going to produce a big new star. For Edmund Purdom, tonight should see the fulfillment of all his dreams.

A long black limousine drove up slowly and carefully stopped at the curb in front of the theatre. As the door opened, an excited throng of fans pushed nervously forward, inching their way just a little closer, eagerly hoping to get a glimpse of the’ picture’s star. A low moan was heard as they disappointedly discovered it was not Edmund Purdom.

Five minutes before the CinemaScope spectacle was scheduled to flash upon the large screen. every seat in the tremendous theatre was filled, except for two center seats reserved for the star and his wife. Heads jerked back and forth, watching the entrance, anticipating their arrival. Five minutes later, the picture went on; the seats remained vacant. The Purdoms never arrived.

Why did Edmund Purdom fail to attend his own premiere?

Rumor the next day blamed his absence on a tiff with his wife, which left the young Englishman sulking alone in his room. Others said he was ill. Still others blamed it on “first-night” jitters. Before accepting unsubstantiated explanations, it is wise to remember that even before “The Egyptian” was finished, Edmund Purdom had already become a part of the Hollywood legend. His own personal story is fantastic enough to make any rumor sound plausible. However, those close to Edmund and his lovely wife Tita do admit that success has changed him.

Little more than a year ago, reject studio files classified him as a tall, serious young man, with dark wavy hair, brown intense eyes, an olive skin and a frightfully British accent. If files were less personal they might have added, current status: unemployed, poverty-stricken.

Today, Edmund Purdom is Hollywood’s fastest-rising young star. Two studios have already invested $15,000,000 in him, and after pinch-hitting for two important actors, Mario Lanza in “Student Prince” and Marlon Brando in “The Egyptian,” Edmund found himself famous before the public even saw him on the screen.

But even a guy with the drive, stamina and talent of Edmund has a hard time keeping up with the sudden change of pace. It is said that he is nervous, temperamental, frequently upset and frequently ill. No doubt, these temperamental differences were responsible for Tita’s divorce suit. Suddenly, with success, with the attainment of everything he and Tita had hoped for when they barely struggled to keep going, Edmund Purdom has discovered his whole life has changed. Every personal conviction has been challenged; every moment of his time monopolized; his privacy completely shattered and his independence restricted.

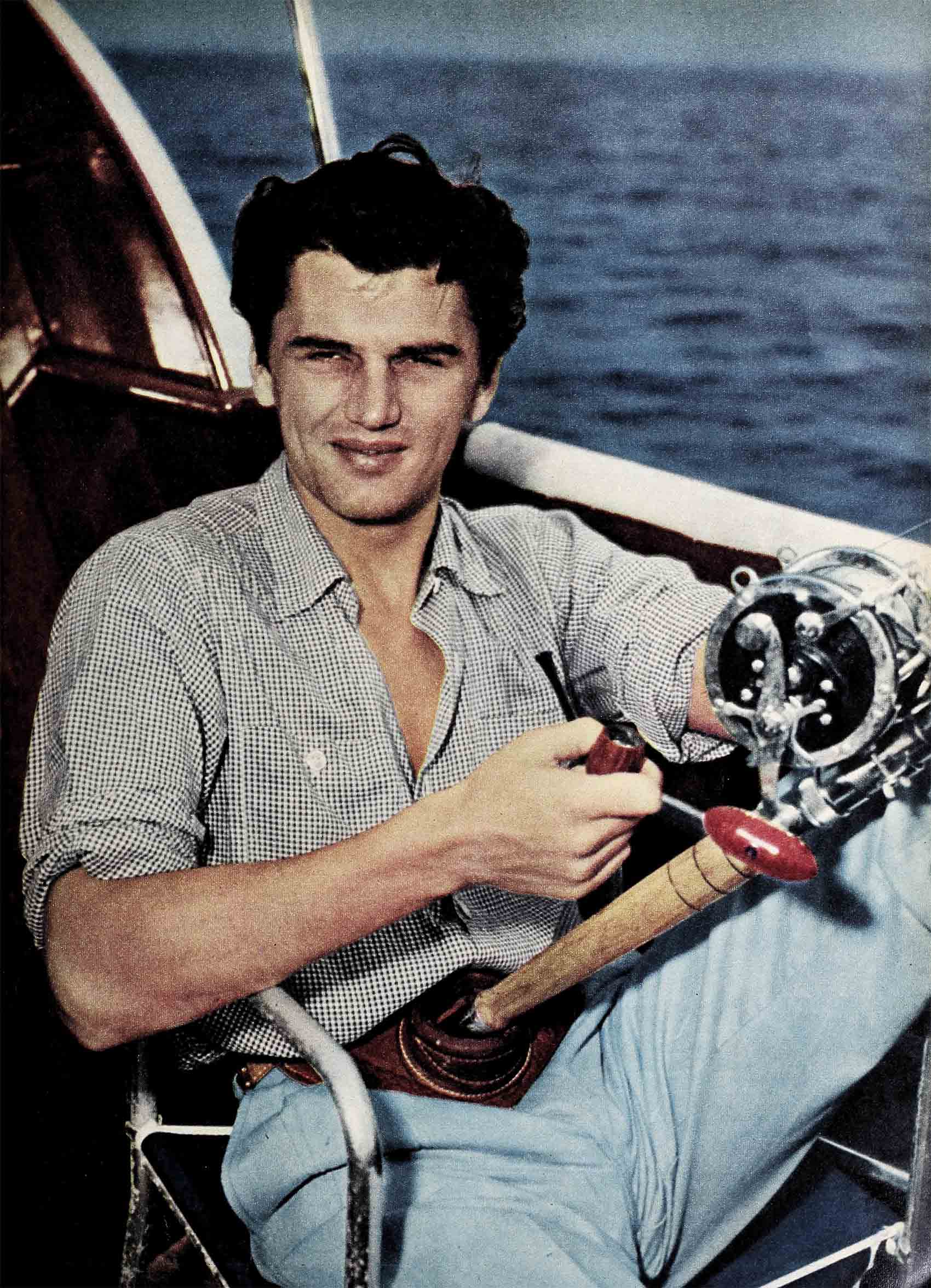

He loves to be with his family—Lilan Ellery, two, and Marina Ann, six months—he loves to just sit and listen to music, he loves to tinker with anything mechanical. Today with his new demands he has no time. He’s a voracious eater, but when he’s working, he can’t eat because he’s too nervous—and these days he’s working constantly. He detests unnecessary noise, can’t stand being tied down by a clock, yet his entire existence is regulated by the clock and constantly surrounded by the unnerving noises of the movie set. A natural athlete who once played rugby, cricket, hockey, who swam, rode and played tennis for relaxation, he now finds he is too tired after a long day at the studio to enjoy physical activity. While before his wife and his home were the only, and the most important, things in the world to him, today he is surrounded by so many demands, so many new people that he feels guilty he has only leftover hours for them.

Edmund’s overnight emergence as a star also places upon him the added burden of proving himself good enough to stay at the top. He’s now appeared in five pictures, having the lead in three. His next is “The Prodigal.” But to date, Edmund hasn’t seen any of them. “I did get a sneak look at some of the rushes of ‘The Egyptian,’ ” he said. “The experience frightened me. If I’d been the executive I’d never have hired me. . . .”

Aware of the gigantic bet which the motion-picture industry is making on him Edmund is often attacked by a violent case of the jitters. He wouldn’t be a bit surprised, he said recently, if in a year or so the M-G-M executives come around, tap him on the shoulder and say: “Sorry, old boy, but we guessed wrong. You’re through.” For the first time in his twenty-eight years, Edmund Purdom is asking himself, “Can I do it?”

Co-workers, studio executives, friends and acquaintances of Edmund Purdom who know his story say there isn’t a possibility that he won’t make it. The boy’s got too much talent, too much drive, too much sensitivity and willingness-to-learn to flop out of the game. Says his dad about his recent success: “I’m not at all surprised. Edmund always was a determined boy.”

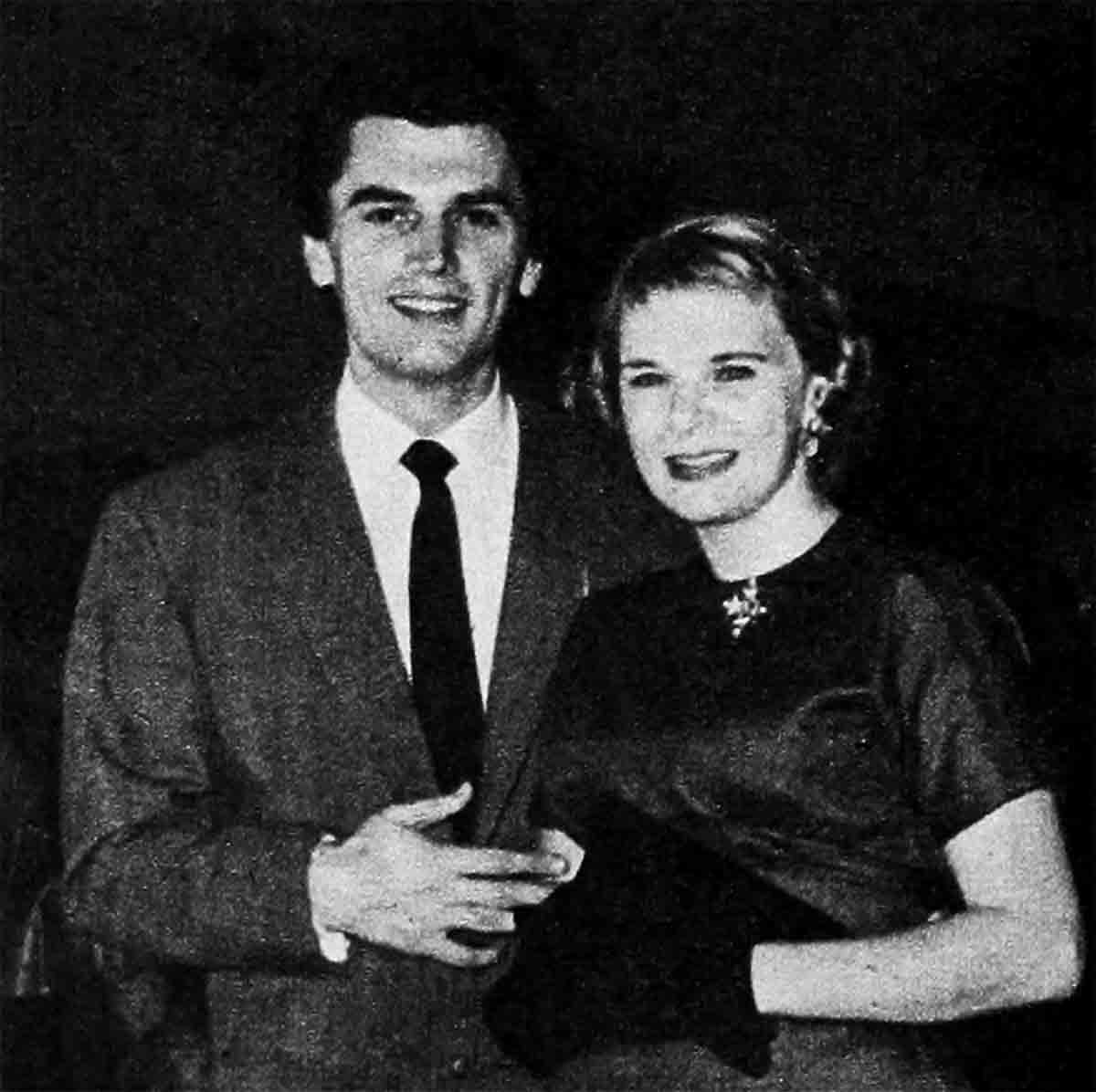

He was born, prematurely, Edmund Anthony Cutlar Purdom in Welwyn Garden City on December 19, 1926, determined, his family says, to arrive on time to share the Christmas festivities. He attended private schools and came home on vacations just frequently enough to dismantle all the clocks, locks or whatever mechanical gadgets were around. At this time, he was determined to be an engineer. Later in school he specialized in electronics, math and science. It was while sitting over a math examination that it suddenly occurred to him that he wanted to act. He put down his pencil, got up and left the room. From that day forward, he was determined to be an actor. He approached the director of the Northampton Repertory Company and asked for a job. Extraordinary as it seems, he was hired at once without any experience. At twenty-one he got his first role, as that of a “forty-year-old detective who never stopped talking” in an Edgar Wallace play. In six short months he appeared in four plays before joining the Army for six months. Following his discharge late in 1947, he returned to repertory and did five plays, then went to London where he won the lead in a musical called “Golden City.” It was while appearing in this musical that he spotted, wooed and won a beautiful blond dancer known professionally as Tita Phillips. They married on January 5, 1951 with nothing more substantial to bank on than Edmund’s determination that he could, somehow, support her. An introduction to Laurence Olivier got him, without an audition, a small part in “Caesar and Cleopatra,” which brought him over to America.

The next period in young Edmund’s life is called by him, “My Near-starvation Period.”

When Edmund made his decision to leave the part he had in Laurence Olivier’s and Vivien Leigh’s “Caesar and Cleopatra,” then appearing in New York, and accept Warners’ $600 advance and ticket to Hollywood, the future looked rosy. Practically every studio in Hollywood had offered him a screen test. If the Warners test flopped, he always had a chance at another studio. So he sent for Tita, who had remained in England.

Things didn’t work out at Warners and his option was dropped. A few other leads turned up and he tested for them but other actors were signed. Nothing was happening. A long talk with Tita one evening led to a unanimous agreement: They’d stick it out until their visas ran out. Little did they know how long and to what lengths they would have to go in order to live up to their promise to one another. For things didn’t happen quickly for Edmund here. This was hard on the nerves, not to mention their slim purse.

By this time, he and Tita were expecting their first child. Groceries were hard to come by because they were not permitted by the immigration authorities to accept work other than acting. Moreover their time limit for residence in this country was rapidly running out. Friends and casual acquaintances came forward with small loans. “I was literally a stranger and they fed me,” he says. “Greater kindness than people here showed exists in no other place on earth.” With the small amount that he could borrow, he and Tita were able to pay the rent on the thirty-dollar-a-month garage on Berendo Street which they called home. They had no refrigeration, only cold water, and they furnished it with a bed and two chairs. Tita lived in one dress and Edmund had one shirt which Tita washed out every night. Often eating depended upon an invitation from an American friend or pawning Tita’s wedding and engagement rings and her father’s watch. The tragedy of it all was that both Tita’s and Edmund’s parents were eager to help but weren’t permitted to send money into a dollar country.

When it became apparent that there was to be no money for doctor’s bills or the hospital, Edmund, frantic with worry, asked their great friend, Millie Gusse, Panoramic casting director, if she could suggest a charity hospital where Tita might go. Appalled, Millie arranged to have her brother-in-law, Dr. James Winsberg, take care of Tita. He supplied her with pills and vitamins and offered to deliver the baby as a “professional courtesy,” since Tita’s father and brother were both doctors (Tita’s father had been attending physician to the Sultan of Jahore).

Just a few days before Tita was to enter the hospital, M-G-M sent for Edmund to audition for a role in “Julius Caesar.” Hardly believing his ears, he put on his only shirt and hitched a ride as far as the Fox studio on Pico Boulevard. After waiting some time for another lift, he resorted to hiking the rest of the way—a matter of five hot miles. He finally arrived, tired, dirty and hungry, but he won the two-line, two-day part as the dutiful servant who helped fatally stab James Mason. With the $150 advance he borrowed from his agent Paul Small, he went over to the Culver City Hospital and arranged for Tita’s entrance. Lilan Ellery, nicknamed Mrs. Doody, was born a day later, October 11, 1952. The $150 permitted Tita to stay in the hospital three short days, then she went back to her one-burner stove and uninsulated garage.

The Purdoms’ troubles were not over. They were still hungry. “There were times during those dark days when we were living in the garage,” Edmund remembers now, “that the sight of people sitting up at a counter in one of your marvelous drive-ins, eating a big fat hamburger, would send me stark, staring mad.” They still faced deportation. “No contract, no extension of your visa,” the Immigration Service warned them. The difficulty was they didn’t even have the money to return to England. American taxpayers were saved the expense of deporting the Purdoms when 20th stepped in and awarded him the role of Brian Aherne’s first officer in “Titanic” at $300 a week.

“You’ve heard the remark the great director, Bill Wellman, made about hungry actors being the best actors? Well, maybe. I do know that when they tested me for ‘Titanic’ I pulled out all the stops. And it was a good thing nobody left his lunch around. I’d have snapped at it like a wolf.”

Meanwhile, Metro, who had taken a thirty-day option for a long-term contract, learned that Zanuck wanted to sign him. At the last hour, a few days before his visa was to expire, they offered Edmund a test. “You can imagine the strain I was under when I made that test,” says Edmund. The result was a contract, inked and delivered the day on which the Purdoms’ visa died. The date is firmly fixed in Edmund’s mind: December 20th, the day after his birthday.

With his new contract, Edmund’s salary was fixed at the tremendous sum of $350 a week and he and Tita and Mrs. Doody moved, with bed and chairs, to a little apartment above the Sunset Strip.

Edmund was scheduled to play Greer Garson’s brother in “Interrupted Melody” when Greer quit the studio. Just about the same time, another artist walked out on another film, after making the song recordings. The star was Mario Lanza and the picture “The Student Prince.” What happened next is part of film history. For the next three months, Edmund’s world consisted of dancing and fencing lessons, rehearsing dialogue and learning to “sync” to Lanza’s voice. The only time Tita saw him was when she lunched at the studio commissary. But he won the role. The next two months were spent preparing for the picture. When they finally started shooting it took only twenty-three days to complete. By the time it was finished, Edmund Purdom was famous. He was offered a test for Marlon Brando’s role in “The Egyptian.”

So certain that he wasn’t going to be given the role, Edmund took a brief vacation in Mexico with Tyrone Power. “But I was waiting and desperately hoping,” he says. “We were in a village about 100 miles outside of Acapulco when a call came through from my agent. ‘Hurry up and get back here,’ Paul Small yelled over the wire, ‘You’re all set for “The Egyptian.”’ I nearly fell dead. Fate was literally showering me with favors.”

Fate has continued to be kind to Edmund’s career. He has already finished “The Prodigal” and “Athena”; his salary is excellent; his home charming and comfortable; his two daughters and Tita well-fed and secure. For the first time in their marriage Edmund and Tita have financial security. But it is equally true that for the first time they are facing an intangible problem. It is not a problem that can be solved by working hard, skimping on food or walking to work. The problem is personal and one of adjustment. It calls for a reshuffling of goals, a new approach to living, a rescheduling of tomorrow. It almost calls for a restatement of what Edmund wanted. Since Tita filed for divorce, Edmund Purdom is asking himself what does he want, what is success, can he regain personal happiness?

When recently discussing his rapid rise, he said, “If I’ve had success I think it’s only made me a little cynical. There is such a thin line between success and failure. I know there are better actors than I (and right now a lot hungrier ones) walking the streets of Hollywood. Do I think the pattern of one’s life is set in the beginning? No. If you want something desperately, you’ll eventually get it.”

And, in his own way, Edmund has answered his own question: “Can I make it?” For the memories of the insecure months that have recently passed will be dimmed and the confusion of recent success will be smoothed out, if he sticks to his belief: “Never be complacent about yourself, even if you’ve been fairly successful. And keep your head up always.” Edmund may be walking a tightrope today, but we think he’ll make it.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1955

No Comments