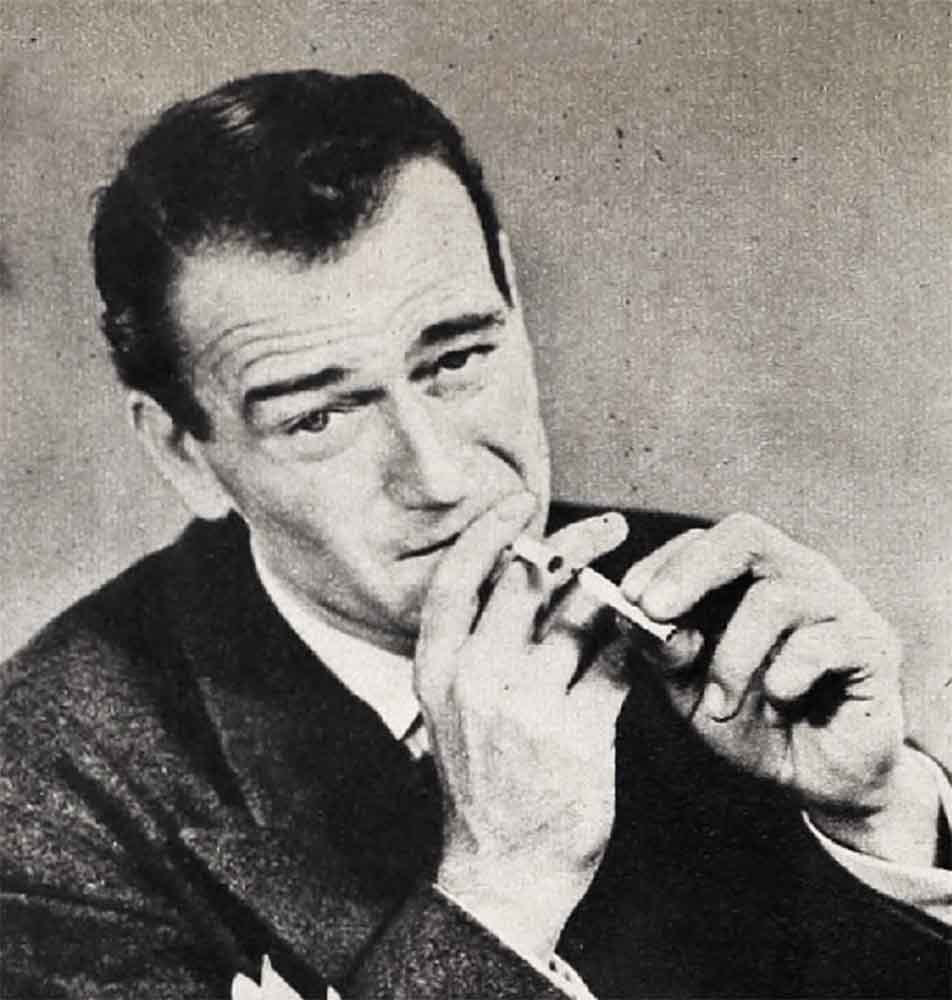

Duke In Coonskin—John Wayne

They are calling John Wayne the miracle man of ’49. He will go down in movie mythology as the blue-eyed Hercules, altitude six-four, weight 220, who, single-handed, lifted Hollywood out of hysterical depression and set her highballing.

The war boom cracked last winter. Movie business seemed perishing of anemia. The cheerful crackle of popcorn had subsided in theaters to what sounded like the death rattle. Then, bang! Hercules Wayne arrived like the Red Cross with transfusions of “Red River,” “Wake of the Red Witch,” and red blood.

AUDIO BOOK

Business jumped and the com popped. Nine first-run theaters in Los Angeles showed his rugged features simultaneously. Out of nowhere, his popularity kanga-rooed to fourth place in the exhibitors’ poll. Theaters everywhere screamed for more of his plasma. The old Wayne blood bank was tapped for reissues as far back as 1931.

Pukka sahibs of major money-losing studios said, “What’s he got that we haven’t got, besides blood?”

It was a fair question. The boy has been around for twenty years. His acting has shot down no Oscars and his sex appeal has swooned no lady columnists into listing him among those they would choose to be wrecked by on a deserted divan.

It was easy to say that folks wanted Westerns. But Westerns have always been with us. And Wayne is not strictly a horse opera diva like Hi Ho! and Hop-along. He owns no hoss. Never has. His covered wagon is a Cadillac.

It’s true he was the first singing cowboy. But he couldn’t sing, he was no cowpoke and they had to show him where to put his hand on the guitar. Yet, the picture he made in three days for seven thousand doughnuts, is still good today.

Raoul Walsh was first to get a load of it when practically knocked off his director’s seat by a giant, rangy, prop boy ambling across the set.

“That’s the guy for ‘The Big Trail,’ ” Walsh said. He got out a contract and said, “Sign here. What’s your name?”

“Duke Morrison,” the prop boy said.

“From now on it’s John Wayne,” Walsh said. “And don’t you forget it.”

“Yes sir,” said Duke and promptly forgot. To this day, he is Duke to one and all of his loyal gang.

The name has no royal connotation. “I had a dog named Duke,” the Duke says. “I was named after him.”

Back in Winterset, Iowa, where he came o life, he was christened Marion Michael Morrison by his Scotch-Irish parents.

Duke Morrison was a celebrity before he was John Wayne. It took him years to eclipse his fame as the football star Trojan tackle. Director John Ford was one of his fans. He gave him a job in the prop department for summer vacations.

Duke starred in his first picture but there were no frantic phone calls from agents. Having no confidence in himself as an actor, he headed back toward the prop department. “I was a prop man at heart,” he says. “I still am.”

Every so often in his bucking career he steered toward props, until one day, John Ford let out a roar that made him jump two feet. “Cut it out!” Ford bellowed. “You are going to make a lot of money in this business. You’ll thank me someday.”

The Duke not only thanks Ford, he worships him. It was in Ford’s “Stagecoach” that he turned the corner. He and Ford and Ward Bond practically lived together at the Athletic Club or on Ford’s boat. You couldn’t find one without the others.

Ford is a man who inspires fanatical devotion, So is Wayne Ford works with a close-knit creative band of old-time friends known as the Ford Group. The Duke has his circle of stout buckos. He carries more men on his personal payroll than any man in Hollywood.

The Duke needed no such instruction as Polonius gave his son; he was imbued with it: “Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried, grapple them to thy soul with hoops of steel.”

That is the secret of Wayne’s strength as man and producer. It is the secret of success in pictures; collaborative team work. The greatest stars have had it; Harold Lloyd, Doug Fairbanks Sr., Charlie Chaplin.

With Wayne it is more than business, it is a personal ideal. He’s a man’s man, practicing the all-for-one-and-one-for-all.

You get it the instant you are wafted on to his set by the mood music of an accordion in the hands of maestro Tony Travers. It takes you back, like a magic carpet, to the good old days before movies talked themselves to a standstill. Every set had its accordion, fiddle or organ. No star thought of emoting without mood music. But now, with the mike around, players cannot act by music. Wayne brought music back to the set to keep the crowd happy and to subdue their restless horsing around between takes.

It looked like a big Western family on the “Fighting Kentuckian” set at Republic. In one corner, the Duke in coonskin cap, suede jacket and dirty horsehide pants was playing chess with his stand-in. Grant Withers, Paul Fix, Bob Morrison—the Duke’s brother who is assistant director—and other compadres straddled around shooting the breeze.

Grant Withers is a charter member of the Duke’s fraternity. They became friends through the Young family. Grant was the husband of Loretta. When Wayne married Josephine Saenz, daughter of the Cuban consul in Los Angeles, the ceremony was held in the Withers garden.

Paul Fix coached Wayne in acting when he was no great shakes and needed confidence. Today, Fix is the Duke’s alter ego in production, working over scripts with him and advising on details.

More than a star, the Duke is creator of all his pictures, though he was not screen-titled as producer until he made “Angel and the Badman.”

He has an analytical mind. “Too analytical,” Fix says. “Too critical of himself, a stickler for perfection.”

His overworked conscience threw Duke an ulcer after “Tycoon.” A steak-and-potatoes man, he then went on a diet of potato soup with his customary concentration and it still is his favorite dish. He gave up black coffee and cut out cigarettes. Now, recovered, he eats everything and again snaps his cigarettes so that ashes rain over everything as from a volcano.

The erupting ash is the only thing that ruffles his beautiful placid wife Esperanza, to whom he was married in 1946, after divorce from Josephine.

Esperanza Baur starred in three Mexican pictures before the Duke arrived on the scene. Her family, which has lived in Mexico for three generations, is French, She idolizes the Duke and begets idolatry not alone from him, but from his men, who believe she has done much to increase his confidence in his potentiality. His one weakness has been his ego.

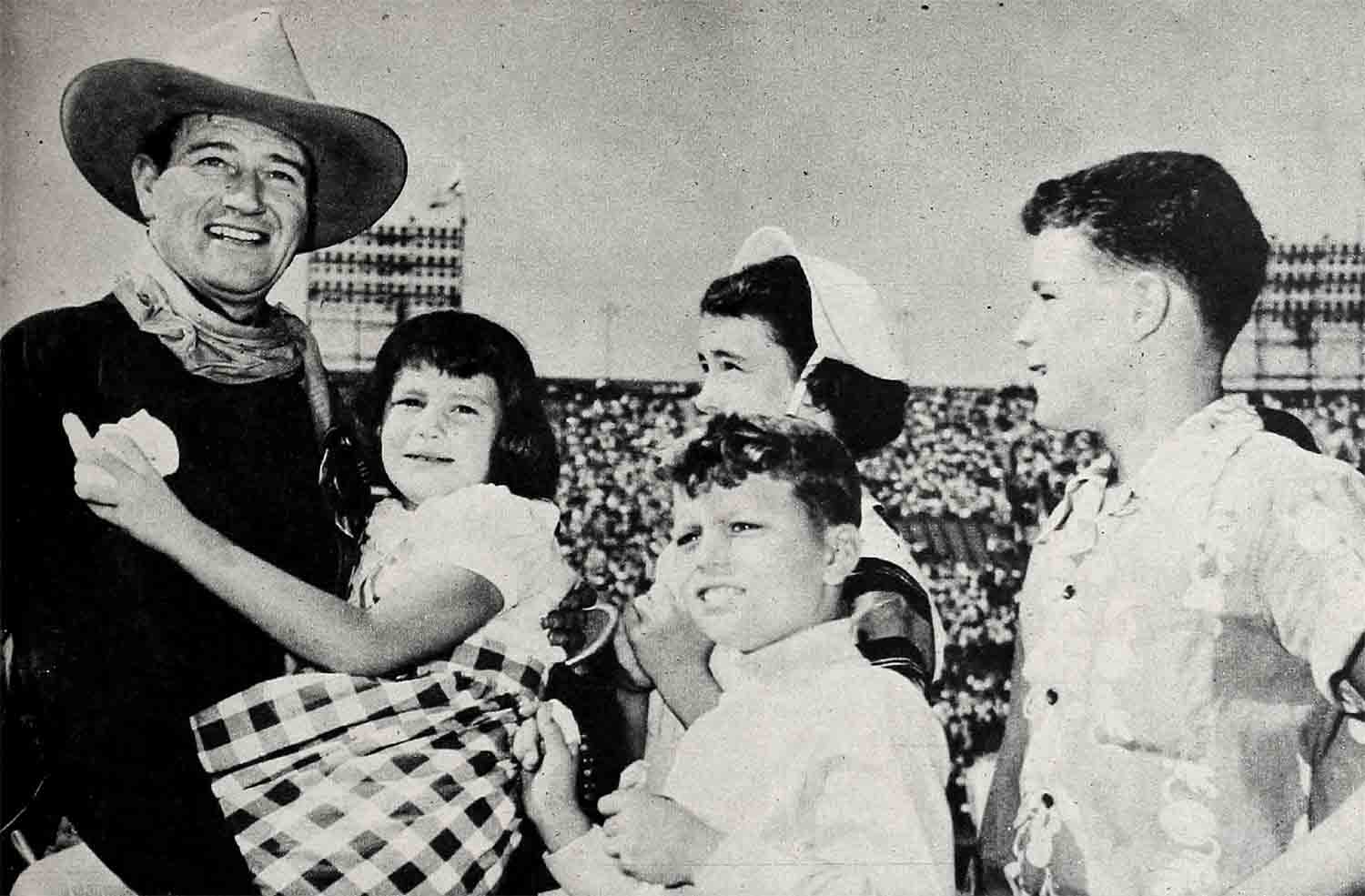

The great social event each year is taking his four kids to the circus. They are his chief joy and he has them around him as often as possible.

The Duke and his duchess live in a large spreading California ranch-type house on an acre of ground in San Fernando Valley. Its furnishing is American; copper, and coffee-grinder lamps, and furniture capable of bearing heavy loads.

Esperanza says they cannot be elegant because the Duke puts his feet on and in everything. She is resigned to this but bursts into mad chirrups over the flying ash. She is aware this does no good and probably amuses the Duke. He is not as calm as Esperanza. His Irish temper goes up like a rocket, comes down as fast and all is forgotten in five minutes. If feelings get hurt, he is remorseful.

Men like him because he is outspoken. You know every minute where he stands.

Grant Withers sums him up for all the Duke’s men when he says, “He’s the champ, for my money. Always plays fair. The best friend in, the world, the most loyal person. Watch the guy. He will make a great director someday.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1950

AUDIO BOOK