No Time For Company

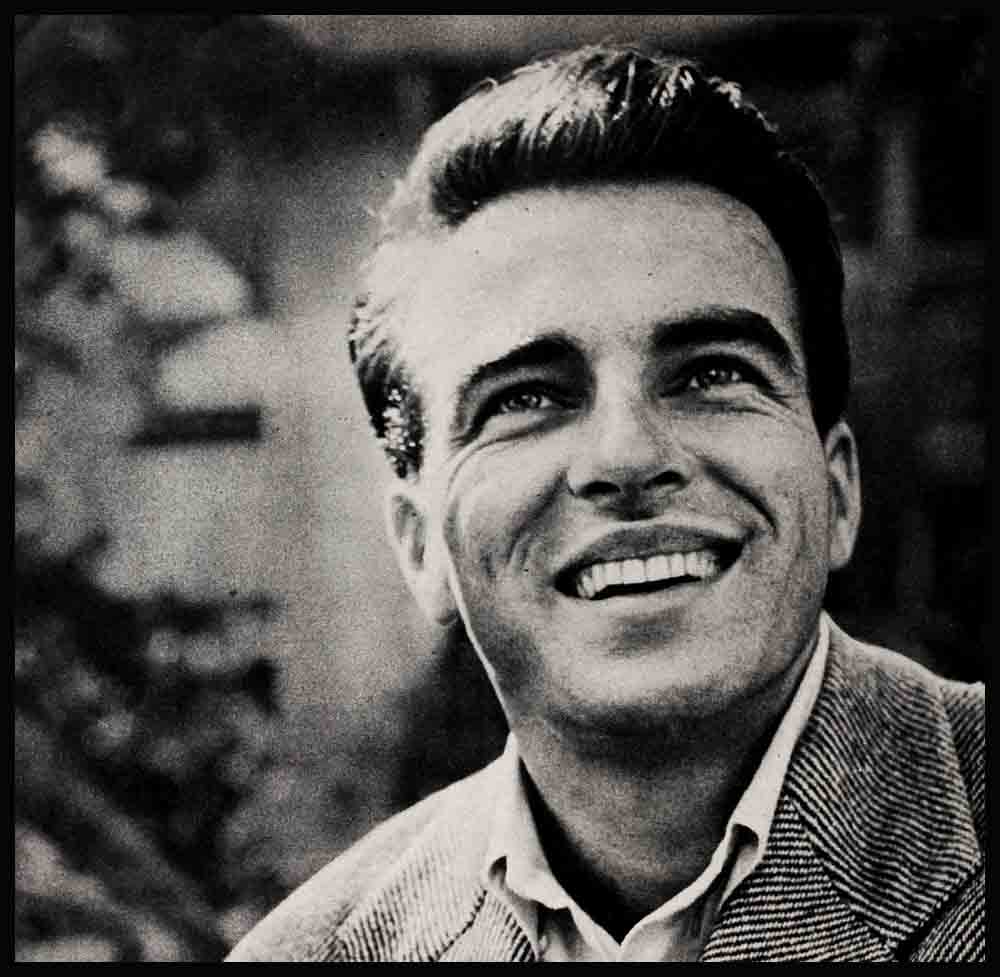

Recently, when Montgomery Clift was working on “Two Corridors East” in Berlin, he wandered into the American Press Club one day. The wife of a radio commentator, glancing at him, asked her husband curiously, “Who’s that? A new reporter for ‘Stars and Stripes’?”

No one in the club guessed that the thin, unobtrusive young man in. the open field jacket and rumpled GI khaki was the sensational new Hollywood star. At first look, he did, indeed, seem just another youthful soldier-correspondent for the Occupation Army’s newspaper or, perhaps, a GI from the Press Center’s motor pool.

However, that wasn’t the only wrong guess Berlin’s American colony made about the unfathomable Monty.

During the six weeks that he worked on his new Twentieth Century-Fox movie about the air lift, and while he lived in one of the houses set aside for the American press in Berlin, he was called a lot of contradictory things; “a shy, modest, retiring sort of guy,” “an egotistical fraud,” “a very warmhearted generous man,” and “an anti-social snob.”

Actually, during Monty’s stay in Berlin, exactly three people really got to know him. The first of these was his driver, a twenty-six-year-old Berliner named Guenther Henkel, who is vociferously convinced that Monty is “one of the finest Americans ever.”

Henkel, who drove the car which the studio rented for Clift’s use, was “sold” on Monty on first meeting. “For two hours after I reported to him the first day, I sat out in the car waiting for him, wondering what he was like. Then he came hurrying out of the house, jumped into the front seat beside me and asked me to take him to the studio. On the way out, he asked me all about myself, about my life history. I told him I had been a lieutenant in the Luftwaffe, and had spent the last two years of the war in prison for insulting Hitler when I was a little tipsy, one night. I don’t think he believed me at first, but after I showed him my prison records and the scars from the beatings I got, he put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘You’re all right, Guenther.’ ”

Henkel still can’t get over another thing that happened that first day. As they arrived at the studio, he said to Clift, “Here we are, sir,” and jumped out to open the car door for the star. Monty looked at him queerly and said in a stem voice, “You don’t have to open or close the doors for me, Guenther. I’m a big boy. I can do it myself. And don’t ever call me ‘sir* either. You can say yes or no without any sir. If you want to call me anything, call me Monty.”

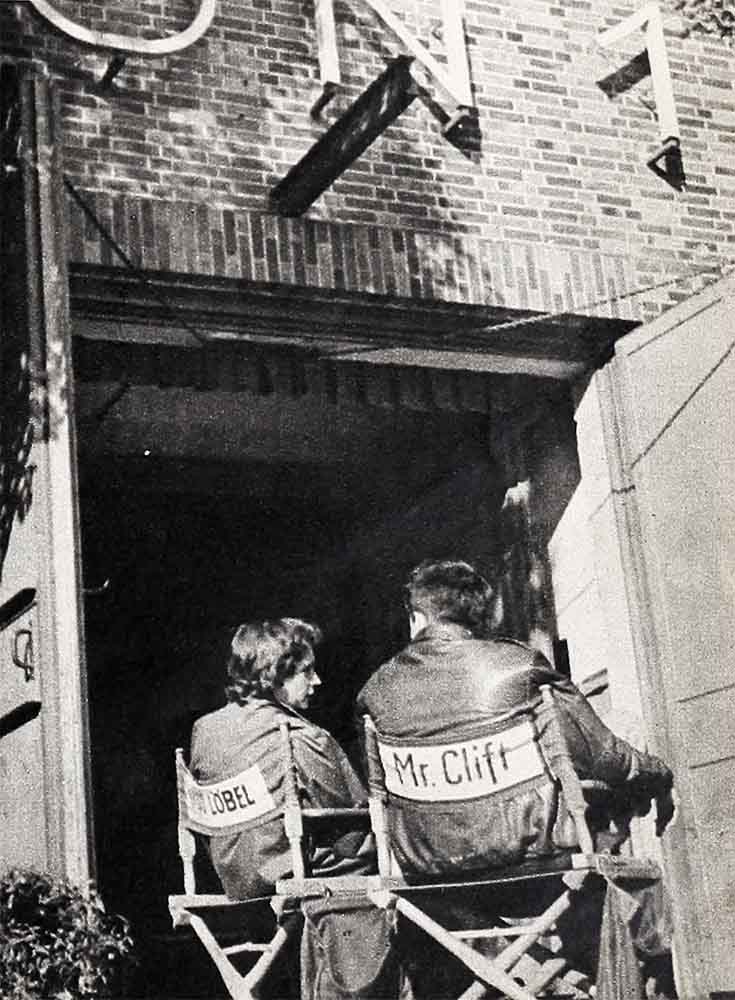

Henkel shakes his head in wonder. “Imagine that. Of course,” he adds, “I never did call him Monty. That would not have been proper. But he never let me open the door for him again, and he frowned whenever I called him Mr. Clift.” Henkel’s hours, like Monty’s own, were long and irregular. “Sometimes, we would work so late at the studio, I would have to spend the night at Mr. Clift’s house.

“On the nights we got home early, he would have dinner prepared for me and I would eat it in the dining room, while he read the scripts over and over again, long past midnight. I have never seen anyone work with as much concentration.”

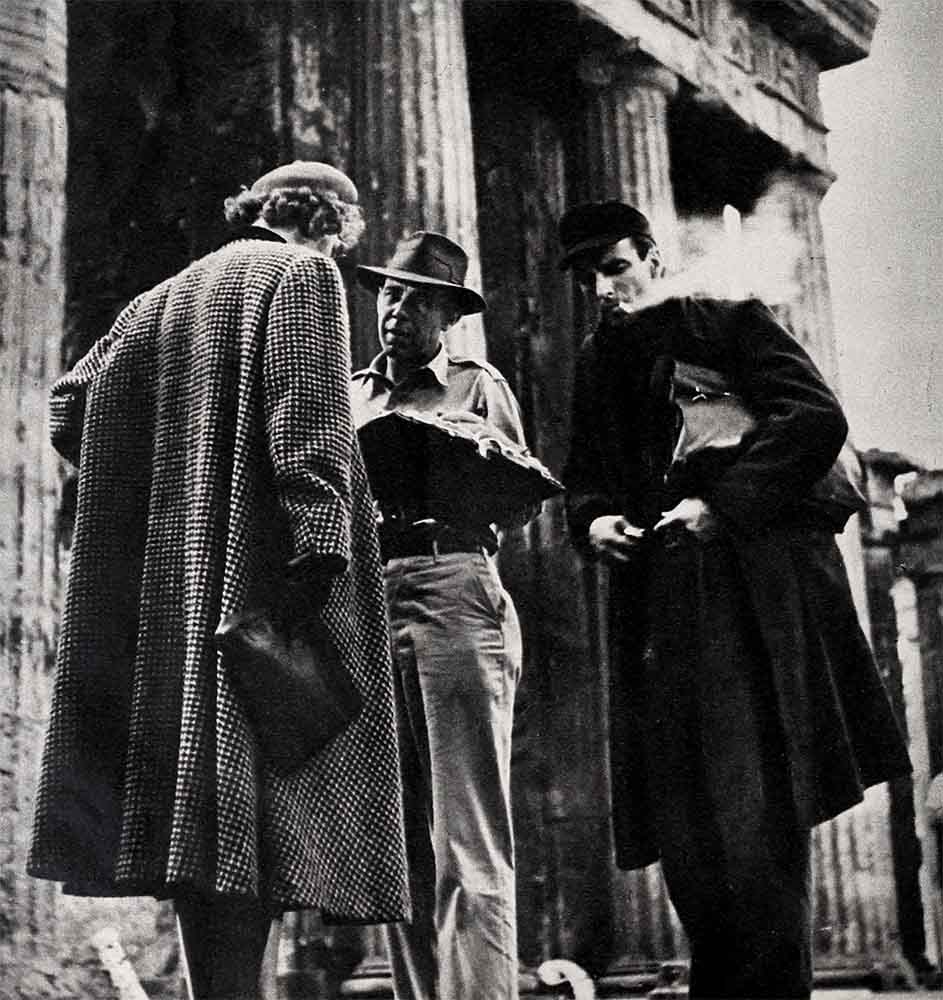

During the whole time he was in Berlin, Monty went out not more than four or five nights, and a couple of these were quiet dinners at the house of director George Seaton. Receiving constant invitations which he invariably turned down, Be told Henkel, “I don’t have the time. I have to work.” His only real fling was dinner at the luxurious Soviet Intourist restaurant, about which many spy stories have been written, and a trip through Alexander Platz, the shabby square in the Russian sector where Berlin’s furtive black marketeers gather.

Because he elected to live in semi-seclusion, few members of the film company jr the Berlin community saw him off location. For a few days, he made quiet appearances at the Press Club, mostly alone, occasionally with some GI companion. Then, even these ceased.

Henkel, constantly on the set watching Monty, says, “Each scene he would play with concentration and if it wasn’t perfect he would willingly play it over and over again. They shot a scene in which Mr. Clift kisses Cornella Burch, who plays opposite him, at least twenty times. Mr. Clift put as much enthusiasm into the last time as the first, not that I blame him so much. She’s some fraulein! But he scarcely spoke to her off location.”

Hard as he worked, Monty seldom lost his sense of fun, according to Henkel. “For his role, Mr. Clift had to learn the song, ‘Chattanooga Choo-Choo,’ ” the driver recalls. “One evening, he sang it over and over for an hour. It was awful! Then, finally, he came out into the dining room, where I was sitting and asked me how I liked his singing. I told him it was ‘very fine,’ natürlich. He just looked at me with a perfectly straight face for a minute then closed one eye slowly and winked.”

And he combined his sense of humor with a determination to improve his, and Henkel’s, linguistic ability. He ordered the driver to learn two new jokes a day and then, on the way home from the studio, tell them to him in German, French and English. Obediently, Henkel scanned the Berlin papers and magazines, and each night would duly and ponderously recite his two jokes. “Mr. Clift always thought they were funny,” Henkel says, “I think.”

The second person who came to know Monty over there was his mysterious secretary, Mira Letts. A handsome woman, perhaps ten years his senior, Miss Letts was Clift’s constant companion. They rode to work together, ate together and worked endless hours in the evening together. Despite the rumors, which, not unnaturally, spread fast and furious among members of the company and among eyebrow- lifting correspondents, there is nothing to indicate that the relationship between the two was anything but platonic.

In fact, Henkel reports that frequently, as the star and his secretary were on their way to the studio, Monty would speak wistfully of a girl back home and the driver overheard the word “marriage” pop into the conversation more than once. And, reserved in almost everything else, Monty excitedly went through the mail every day as it arrived from the Army Post Office, looking for “that letter.”

The third person who had any intimate knowledge of Monty during his sojourn in Berlin was his housekeeper. “Herr Clift would always come out into the kitchen in the evening and we would have long discussions about cooking—always in German,” Frau Liese remembers. “He liked to cook, especially steaks, which he made barbarously rare in that way Americans have, and egg desserts.”

Frau Liese bears witness, as well, to the unique quality of Monty’s singing voice. “I would wake him up at seven in the morning by knocking on the door and then slamming down the window in his room,” she says. “Then, in a few minutes, I would hear the shower and, above it, Mr. Clift singing. Es war nicht schön, aber laut—not good, but loud. Then Mr. Clift would come downstairs, still singing, come into the kitchen and ask me how I liked his voice. I always told him the truth, that I didn’t, and he would smile and say, ‘I know I can’t sing, Frau Liese, but I have to for the movie.’ ”

In all respects, Frau Liese recalls, Clift was easy to work for and pleasant to be with. “He was not haughty nor demanding. He would wait on himself and would always talk to me as if I were a friend, not someone who worked for him.”

The single incident which impressed her most, indeed, almost overwhelmed her, was Monty’s choice of bedrooms. The spacious house, in which the Press Center had billeted him, had three bedrooms on the second floor, two of them large and comfortable and the third, not much bigger than a closet. Clift, after looking them all over, selected the small room—and slept in it during his whole stay.

“Imagine a famous star, sleeping in such a cubbyhole!” Frau Liese clucks. “He said he liked the bed in the small room, but he wouldn’t let Henkel and me move it into one of the bigger rooms.”

Although Monty gained the dislike of some in Berlin because of his persistent aloofness, he gained the affection of a number of others because of his lack of pretension. Among the latter were the German technicians at Tempelhof studios, the make-up artists, with whom he left generous presents on his departure, and a good many of the GIs and airlift guys.

Henkel recalls that there was graphic evidence of this one evening on their way home from the studios. He had been driving fast and, suddenly, heard a siren behind him. He pulled over and a Military Police jeep screeched to a stop alongside.

“Don’t you know you were doing forty- five?” bawled the rawboned MP as he began to write out a ticket. Then, sticking his head inside the car window and recognizing the young man with the piercing eyes, hatless and carelessly dressed in parts of a GI uniform, he chuckled, “If it isn’t Monty Clift. Go ahead, Monty. It’s okay.”

As they drove off, Monty whistled in relief. “I wasn’t so worried about getting a ticket for speeding,” he said. “I was afraid those MP’s would pull me into the guardhouse for being out of uniform.”

No man, they say, is a hero to his valet. Maybe not. But Monty Clift certainly is a hero to his chauffeur and housekeeper.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1950

AUDIO BOOK