Wake Up And Give!

I hit bottom because I didn’t know how to get along with people,” admits blond-haired, green-eyed Jody Lawrance, who is fast on her way to becoming a star. “I didn’t understand people and they didn’t understand me. And, once you gain a certain reputation, in Hollywood or anywhere else, there’s a chain reaction. Before I knew it, I had earned that ominous label, ‘uncooperative!’

“Of course,” Jody continues frankly, “there’s a reason for everything, and I was no exception. But that’s a lame excuse. You get what you give and, although we can’t change the world, we can change ourselves—if we honestly want to change. After six years of struggling to become a better actress, I started over again. The road back was lonely and rough, but it paved the way, I believe, for all the good things that are happening to me today.”

One of these “good things” is Jody’s new, long-term contract at Paramount. Others include her new-found friends and her peace of mind that has led to an optimistic outlook on life. And, most important, there is Bruce Michael Tilton, an airplane company executive who met and married Jody within three whirlwind months.

“Being married to Bruce is the best thing that could have happened to me,” says Jody, reflecting on her good luck. “The timing was perfect, too, because I was too picky and choosy before. But now I’ve learned to evaluate people. Bruce has given me a feeling of security that I never knew. For a girl who, at a party, always used to head for a chair in an inconspicuous corner, it’s a wonderful awakening!”

Jody’s first awakening in life occurred in Fort Worth, Texas. where she was born on October 19, 1930. and : christened Josephine Lawrance Goddard. While still a et young child, she was moved to California and later attended Beverly Hills High School, then a professional acting school. The fact that she was a child from a broken home, may have contributed to the chip-on-the-shoulder attitude which she later developed.

“No matter who you are or what you do,” she sums it up now, “it’s terribly important to feel needed and wanted—especially during those formative years. Sometimes you grow up and discover you’ve developed a chip that anyone can spot. This automatically creates a defensive attitude and, despite all good intentions, you only succeed in fouling yourself up. It happened to me while I was under contract to Columbia Studios.”

Typical of Hollywood, there are numerous versions of Jody’s unparalleled experience. But when she tells the story as it really happened, her expressive face instinctively mirrors the truth. She modulates her voice while her hands remain motionless in her lap. For a fleeting moment a lost look creeps into her eyes and you sense the loneliness that dogged her footsteps along the way. But self-pity has no place in Jody’s make-up; she makes no bid for sympathy, and yet she exudes a wistful, indefinable something that makes you hope and pray she’ll never be lost or lonely again.

I was born independent,” says Jody, “and sometimes this can become a great handicap. I must say, however, that if I had to do it all over again I wouldn’t want to change anything—except to use greater tact, wisdom and diplomacy. More than anything else, I wanted to be a good actress, and my heart was filled with hope when I signed a contract with Columbia.

“Two years and six pictures later I was a very confused and disillusioned girl. There was so much to learn about everything! I needed help and felt, instead, that I was rapidly heading downhill. A studio is like a great machine and the wheels must keep moving. They threw me into pictures such as ‘Mask of the Avenger,’ ‘The Son of Dr. Jekyll,’ ‘Ten Tall Men,’ and other roles that weren’t within my limitations at the time.

“Publicity-planned romances and dates, cheesecake photographs and phony gossip items all play an important part in building a Hollywood career,” says Jody knowingly. “If you’re geared for quick adjustment, I guess you can take it. But it was all so new and it made me feel embarrassed and ridiculous. I believed I wasn’t doing justice to myself or the studio, and so I fought back.

“Now, in all fairness to studios,” Jody adds, “they are in business to make money, and they don’t deliberately set out to do you harm. But, I argued, no one benefits this way, so why force me to do these things? Why not do as you’re told, they countered, and allow us to be the best judge of what’s good for you. By the time exaggerated stories had made the rounds, they had me pictured as a monster directing scenes and rewriting scripts!

“Now a certain amount of kicking around is good for anyone, I believe, especially when you’re vulnerable. You learn how to sidestep and to respect discipline. But once you get bruised you do become overly sensitive. This helps an actress in her work, if it doesn’t go too far. With me, it went too far.

“When I reached my lowest level of despair,” Jody continues, “I asked talent executive Maxwell Arnow to release me from my contract. What he said to me then was true—that many girls my age would have given a right arm for the opportunity I was throwing away. Being reminded of my unorthodox behavior really hurt, and we didn’t part on friendly terms. Fifteen months later, when Paramount announced my new contract, Mr. Arnow sent me a letter. He was pleased, he said, that I had justified his faith in me. This kind gesture gave me a new and heartwarming slant on the men who run the picture industry.” The way Jody says it reflects how very important her new attitude was to be.

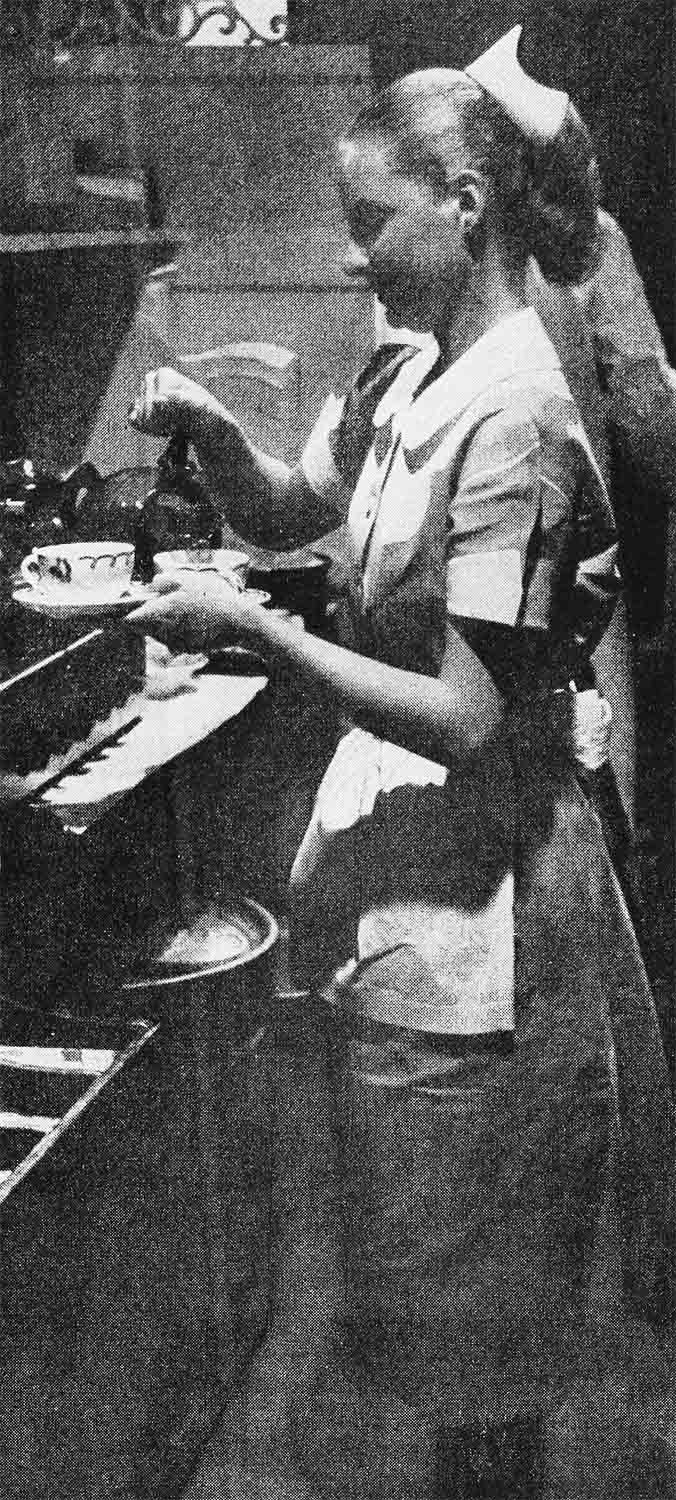

“Free from Columbia,” she goes on, “I took the one course that seemed like the answer to my need. Time to study, the opportunity to learn how to get along with people better, and a chance to make a living—of sorts. Robb’s restaurant at Beverly and Santa Monica Boulevards needed experienced waitresses who looked neat and attractive. When the chips are down you have to bluff your way, but in my desperation I couldn’t have picked a tougher job. I started working on opening night—and, needless to say, they quickly realized that I had lied about my qualifications.”

Jody smiles grimly, remembering what happened. “I didn’t know the lingo used in giving orders to the cook, so I held up the service. And, never having worked in the business world before, I had little in common with the other waitresses. So again I went in with a chip on my shoulder, and being too sharp, too impatient and too intolerant of the customers’ demands, they were quick to sense my antagonism. Naturally, they complained about me, and I was called on the carpet.

“The customer is always right, they warned me. If you expect a good tip you must grin and take your treatment, good or bad. It’s amazing what can happen to people with hungry stomachs, they added. They lose all sense of proportion and a waitress has to accept their abuse and try to protect her own feelings. She learns how to put on a good act and by looking hurt, it invariably makes the complaining customer feel he has done her a great injustice.

“Eventually, I came to realize that, in a sense, it’s like giving a performance and it was excellent training for me.

“It was a lonely life, however, working the graveyard shift—five p.m. to one a.m.—but it left my afternoons free for all the dramatic coaching I could afford. My average pay was twenty-seven dollars a week, with five to ten dollars in tips each night. I know what that money means to a waitress,” Jody grins, “so let anyone criticize me for over-tipping today! If a girl wants to know how to judge a fellow, I suggest that she watch how he treats waitresses. Believe me, it’s a true test of character!”

After a year at Robb’s restaurant, Jody became a waitress at Blum’s candy and ice cream parlor in Westwood, then switched to their famous branch in Beverly Hills.

“By the time I had worked a year at Blum’s,” says Jody, “I had resigned myself to my job, my co-workers and the customers. It’s such a revelation when you stop thinking, ‘I’m right and everyone else is wrong!’ You relax and the pressure lessens. Of course, you can get a martyr complex when you feel like a misfit—but not if you develop a sense of humor. When things got so bad they couldn’t get worse, I learned how to laugh at myself. Once you’ve had this experience, you’re saved! “Far from being ashamed of waiting on tables, I was only afraid people would think I had failed. Oddly enough, and despite my frustrations, I never felt I was a failure in the true sense of the word. So I worked as Jody Goddard, and no one knew I was an actress. Of course, I wasn’t associating with people in the picture business, so agents forgot about me. I had little money for pretty clothes and less time for dates. But this lack was compensated by a new hope. At long last I began to believe I was ready and equipped to handle an acting career.

“What did the future have in store for me? How often I asked myself this!”

Call it fate, faith—or magic. Somebody, or something somewhere was watching out for Jody Lawrance! It so happened that she had worked for TV producer Frank Wisbar before her hectic days at Columbia. He was impressed with her talent and promised Jody he would use her again when the right part came along. And he remembered!

Unaware that her career had taken a nose dive, Wisbar located Jody’s father and left a message with him. Jody got in touch, and was signed for two TV shows. Director Michael Curtiz, who was searching for a certain girl for a certain picture, happened to see one of these shows. Soon, the wheels began whirling again, and the rest is now local history. Where else could it happen but in Hollywood! On the brightest Monday morning of Jody Lawrance’s life, she was summoned to the Paramount studio.

“I read for the role of Kathie in ‘The Scarlet Hour,’ ” says Jody ecstatically. “Mr. Curtiz was very kind and helpful. The studio wanted me and I was signed without so much as a screen test. Yes, I was scared stiff—in an exciting sort of way! After ‘The Scarlet Hour’ I did ‘The Leather Saint,’ with John Derek, and in this one I really had an acting role. It’s so gratifying to feel ready now and no longer frightened and unwanted. Though I still have a long way to go, I am a very lucky girl.”

On that fateful Monday when her new life began for her, Jody tried on her wardrobe, then made the rounds meeting everyone at Paramount. At the end of the day she was an exhausted, starry-eyed girl, but typical of her sense of fair play is the fact that she showed up for work at Blum’s that night. The very next morning she was in front of the studio cameras beginning a bright new life. She was an actress. She had made it!

“I couldn’t leave Blum’s short-handed without some sort of notice—even though it was only a day’s notice,” Jody explains. “But I must say I was walking on clouds my last night as a waitress. Nothing could have touched me, not even my first accident! Wouldn’t you know Id pick that time to christen a gentleman customer with a nice, gooey, chocolate parfait! He was furious and, I must say, you couldn’t blame him. But it still didn’t matter. I just turned on great salty tears and gave an Academy Award performance. My acting was so convincing, his wife became sympathetic and took my side. So she told her husband what she thought of his behavior—and how! It was quite a scene!”

It’s easy to see why, today, everyone who knows Jody is rooting for her. At Paramount, where they have enthusiastic plans for her, they liken her to a “young Bette Davis.” While Jody is grateful for every single thought and gesture, one particular incident touched her heart deeply and her eyes sparkle when she tells you about it.

“A few days after I started at Paramount, the kids I worked with in Blum’s Beverly and Westwood stores sent me two dozen red roses and wished me luck. They don’t have money like that to throw away—who knows better than I! If those kids think this much of me, I hope and pray that I’ll never let them down.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1956