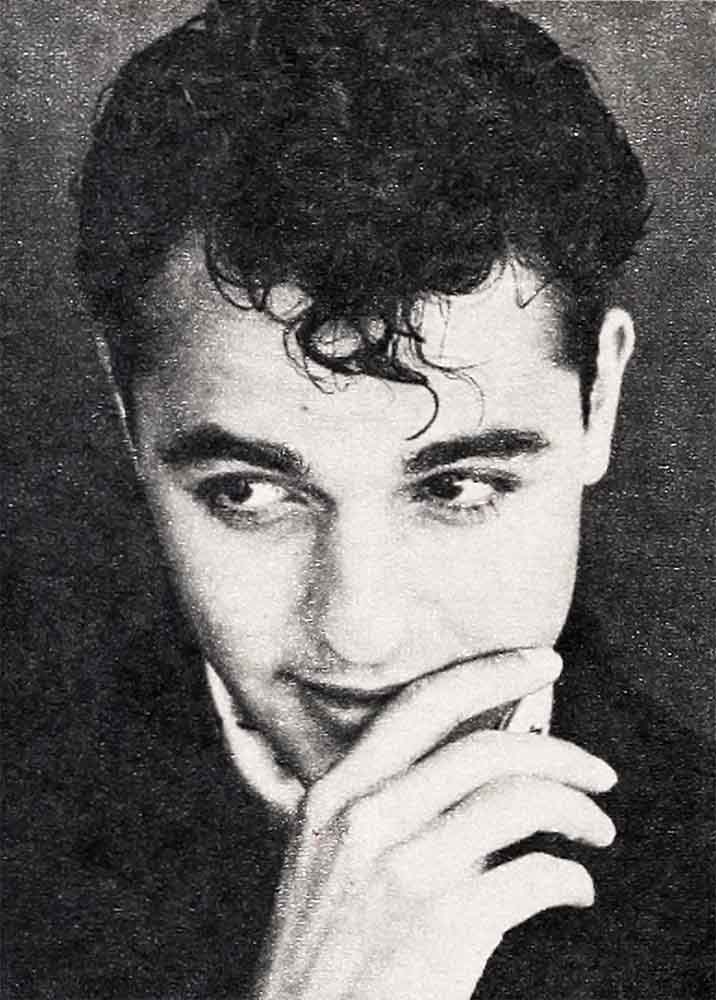

Is Sal Mineo Too Fast For His Own Good?

Soon after you read this, Sal Mineo will step before the bench in Bronx Traffic Court to face the music. The tune is as familiar to Sal now as it is to many other young Hollywood stars whose chief fault in life is their youth.

The charge against Sal is speeding—doing 53 miles per hour in a 40-mile zone on New York City’s Henry Hudson Parkway.

Ordinarily, a speeding rap isn’t very serious when it’s the first offense. That’s what Sal undoubtedly figured when he tilted his speedometer needle too far to the right in October, 1960. He got caught, took a summons, then went to court, anted up a $15 fine and went on driving his snazzy baby blue 1957 Thunderbird convertible with the SM-95 license plates.

Then came the dawn of June 1st, 1961. Sal awakened in his midtown hotel room and looked at his watch. It was time to go, man, go. He hopped out of bed, showered, shaved and jumped into his clothes. Then he hurried down the elevator to the lobby and checked out.

“Have you any bags, sir?” asked the desk clerk as Sal headed out.

“No,” Sal replied on the run. “I checked in just as I am.”

Sal had registered at the hotel the night before, after a busy day in the city collaborating with the writers of his new play, “Something About a Soldier,” which opened on Broadway just recently.

“I was too tired to drive to my folks’ home in Mamaroneck,” he explained. “So I stayed in the city.”

Sal got into his T-bird at precisely 7 A.M. and headed for the West Side Elevated Highway, Mamaroneck bound. He was pressing a tight schedule. Sal had to be back in the city to catch a noon jetliner for Los Angeles. He was going to Mamaroneck to pack his clothes for the flight to the Coast.

Normally, at seven in the morning, traffic on the West Side Highway is beginning to build up, but not in the northbound lanes which Sal was traveling. The cars move south during the morning rush hours, heading into the city.

As Sal tooled along the broad six-lane highway he was saying to himself how lucky he was that he didn’t have to be in the snarl of cars going in the other direction. His side was clear, almost wide open. Pretty soon the West Side Elevated Highway would merge into the Henry Hudson Parkway and he would enter the Bronx. Mamaroneck would then be only a short while away.

Sal’s foot barely touched the T-Bird’s accelerator, yet the car purred along effortlessly. He moved at a swift, steady clip.

Too swift!

Sal knew that when he heard the shrill whine of a siren. A quick glimpse in his rear view mirror told him he was in trouble. The flashing red blinker atop a green and white police car was the signal for Sal to put on his brakes and pull over to the side, near 175th Street.

“Let me see your license and registration,” said the patrolman as he came up to Sal, who remained seated behind the wheel.

Sal took the papers out of his wallet and handed them to the waiting policeman.

“Sal Mineo,” remarked the cop after spotting the name. He seemed pleased with his aptitude at recognizing a famous face. “I thought you were the actor the moment I saw you,” the policeman smiled.

“What’s wrong?” Sal inquired with a squirm of restlessness. Of course, Sal knew he had been going over the speed limit. But this was no time for social amenities. He had a timetable to keep if he was to catch the noon flight to California from Idlewild Airport.

“You were doing 54,” the policeman replied. “This is a 40-mile zone. I’m going to give you a ticket.”

Sal shrugged. He knew he had violated the speed limit, although he wasn’t the only one. As he was driving along at that early morning hour, he was passed by a number of cars.

“Some guys get away with it,” the policeman said, “but some get caught. It’s just your tough luck that I spotted you.”

The cop took out his pen and began to write as Sal sat mutely waiting for the summons. It took a minute to make out the ticket, but during that minute something happened that became significant to Sal in a dramatic turn of events soon to become apparent.

As the policeman wrote the summons, another patrolman cruised by in a radio car and caught the eye of the first one. The policeman next to Sal waved to the passing patrolman, who waved back and kept going.

Sal thought nothing of this—not at the moment, anyway.

The policeman finished writing the ticket and gave it to Sal, saying:

“You had better be careful, Mr, Mineo. I see on your license that you have a previous conviction for speeding in this State. This is your second offense. If you get a third, you’re going to lose your license.”

The New York State law calls for automatic revocation of license if a driver is convicted three times for speeding in an eighteen-month period, a year and a half.

Sal looked at the cop sternly as he reached out to take back his license and registration—along with the newly acquired speeding ticket.

“I certainly don’t want to lose my license,” Sal said with firmness. “I’ll be careful, you can bet on that.”

The cop went back to his car as Sal started out again for Mamaroneck. Now Sal was being overcautious on the pedal. His eyes were almost glued to the speedometer. The red indicator hovered around 39, high enough. He wasn’t going to get stopped for speeding—not again.

But something had happened in the few minutes that Sal had been stopped by the cop. The traffic on the highway had started to build up in the northbound lane. Not a great deal, but enough to make drivers behind Sal honk their horns impatiently, trying to get him to move faster.

When he realized that trying to stay within the legal 40 mph. limit was tying up traffic and raising tempers, Sal stepped it up. Just to stay with the rest of the traffic!

As he went faster, Sal cast his eye on the speedometer, wary about breaking the law again. But he was breaking the law because the indicator showed he was doing 45.

“I was surprised,” Sal said, “because even when I was up there doing five miles an hour over the 40-mile limit, drivers behind me kept beeping their horns. But I knew it wasn’t wise to go any faster, despite the fact that almost everyone on the road was passing me up. I knew I had to be extremely careful because I didn’t want to lose my license with a third speeding ticket.

. “I’ve always been cautious,” Sal explained. “I’m no speed demon. I’m no auto racer. I’ve never been in a racing car. When I was younger I used to like to fool with cars. I did some body and fender work on them. I tried to add more power to the engine once—the car was a 1941 Dodge. That was when I was out in California. I’d say I was about sixteen at the time.

“I put in a dual carburetor—but nothing could help that old heap. I had paid $35 for it, and when I finally dumped it I had to pay the junk man $25 to take it away.

“I got only one ticket while driving that car—for adding to the Los Angeles smog with big clouds of black smoke from the dual exhausts.

“Every day on my way to work at the Warner Brothers lot I had to go over a steep hill in Laurel Canyon. Half way up I would have to pull into a driveway and back up to the top of the hill. The car couldn’t make it even in low gear, so I had to put it in reverse.

“And every day there was a certain cop who watched what I was doing. He left me alone until one day when he finally couldn’t stand it any longer. He pulled me over and asked me what kind of a nut I was. And then he gave me a ticket. For heavy exhaust.”

How about speeding—did Sal ever get ticketed on the Coast for going too fast?

“Never,” said Sal emphatically. “My first speeding ticket was hand- ed me in New York—and so were my second and third ones.”

Third one?

Yes, Sal got a third speeding ticket—driving to Mamaroneck.

He got it exactly five minutes after the first ticket, and this is just the way it happened:

Sal had paid the 10-cent toll at the end of the West Side Highway and crossed the Spuyten Duyvil Bridge over the Harlem River into the Bronx, the borough of Sal’s birth. The highway now became the Henry Hudson Parkway, a wide, sweeping road.

“I was taking it very easy,” Sal related. “I was in the right hand lane. Cars were still honking their horns and pulling around to pass me.

“The next thing I knew—a cop pulls me over . . .”

The cop, believe it or not, was the one who had passed by in a radio car and waved to the patrolman who had issued Sal a speeding ticket five minutes before.

“What’s wrong, officer?” asked Sal, puzzled by the policeman’s action.

“You were speeding. Mr. Mineo.” This policeman didn’t even need the verification of Mineo’s name from his license and registration. He knew this was Sal.

“The first cop must have told him,” Sal said. “I don’t think the second cop could have recognized me that readily. He hadn’t even seen my full face when he called out my name.”

“I clocked you at 53,” the cop said, “and there’s a limit of 40. So you were speeding.”

“What about all the other cars?” Sal asked, the same question he had posed for the first policeman.

“We can’t tag everybody,” the cop answered. “You just happened to be the guy I caught.” (A familiar refrain.) “Let me have your license and registration,” said the cop.

Sal didn’t have to dig into his wallet for them. They were still on the seat where he had put them, along with the speeding ticket, after the last time he’d been stopped.

Sal tried to show the cop the ticket and explain that since he had just gotten one summons for speeding he certainly wouldn’t break the law immediately afterward.

“Sorry,” said the cop, “I’m only doing my duty.”

“But I’ll lose my license,” Sal pleaded.

“Should have thought of that before you broke the law,” the policeman said bluntly.

Then he wrote out the ticket.

Sal took it without further comment, and drove on to Mamaroneck.

“I really breathed a lot easier when I crossed the county line into Westchester,” Sal said. “I don’t think I could have driven much further in the city limits. I was certain the police were out to get me. . . .”

Sal packed at his parents’ home and called a local taxi service to drive him to Idlewild. He wasn’t going to be seen in New York City behind the wheel of that T-Bird.

After finishing his business on the Coast, Sal flew back to New York. On November 10th, he went to Manhattan Traffic Court to answer both tickets.

“How do you plead?” asked Magistrate Louis S. Wallach.

“On the first speeding offense, guilty,” replied Mineo. “On the second, not guilty.”

The court immediately levied a $50 fine on Sal’s guilty plea; the punishment was severe because this was a second offense.

When Sal pleaded innocent to the second speeding charge, it meant there would be a trial. At the trial, the cop who issued the summons must appear and testify. Sal also must testify.

Magistrate Wallach set the date—January 16,1962. The case was ordered heard in Bronx Traffic Court because the summons had been issued in Bronx borough.

Sal is confident that when the court hears his side, it will dispense of the case in his favor. He insists on his innocence.

“You have all the facts—I’ve told the whole truth,” Sal said in telling this writer his story. “I’m going to tell the same story in court because there’s no other way to tell it. I think I’ve been given a fast shuffle.”

Sal, who was interviewed in the presence of his attorney, Lewis Harris, vowed to get rid of the baby blue Thunderbird which seems to attract cops like a magnet.

‘Tm giving the car to my sister who’s going to Bridgeport (Conn.) College.”

“Yes,” chimed in lawyer Harris, “and Sal’s going to get himself an ordinary car with a long license number.”

Sal smiled, turned to your reporter with a wink, and said: “Yeah. a purple Eldorado Caddy with license SM-1.”

Naturally after his one-two double brush with New York’s lawmen, we wanted to know whether Sal was sour on cops.

“I like cops,” Sal replied. “As a matter of fact, I appeared only recently at a Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association affair in New York City. I get along fine with cops—except the ones who are out to get me.

“I know that last one had no business picking on me. I just wasn’t speeding.”

That’s Sal’s case.

It should answer the question raised in the title of this story: “Is Sal Mineo Too Fast For His Own Good?”

The editors and staff of Photoplay do not condone speeding.

We have no sympathy for speeders and endorse the strictest police and court action against those who violate the law.

“Speed kills” is not a meaningless slogan.

Yet, in New York City, several studies have indicated that the 40-mile-an-hour limit on certain parkways and expressways is unrealistic. The Automobile Club of New York is one of several influential groups which have campaigned for a higher limit.

A New York newspaper conducted a special traffic survey with its own staff in behalf of Sal Mineo’s case and found that most cars travel on this road at an average speed of 50 miles an hour!

The survey also showed that policemen invariably ignore cars that do a shade or so over 50—provided the entire stream of traffic is cruising along at that rate of speed.

And the survey showed this is a fact in repeated tests along the West Side Elevated Highway and the Henry Hudson Parkway, as well as on other parkways and expressways in the city—the Belt, the Cross-Bronx, the Grand Central, the Van Wyck and East River Drive.

As a general and widely-practiced rule on New York City’s parkways and expressways the police, whether on motorcycle or in radio patrol car, just do not stop a whole string of cars which do 50 or 51 or 52 or even 53 miles an hour in a zone with posted limits of 40 to 45 mph!

The cops may clamp down on an individual driver doing 50 or over, if he’s alone on the road. But during the peak travel hours, when heavy traffic doesn’t slow the motorists, the average speed is somewhere between 49 and 53 mph.

And the cops cruise along with this traffic and make no attempt to single out a motorist—unless he exceeds the speed of the other cars. During the bumper-to-bumper rush hour, of course, cars will only crawl along. No one can speed.

The Police and Traffic Departments have promised to raise the limits, but are being held up by their own studies recently undertaken.

Elsewhere in the Metropolitan New York area, speed limits range up to 60 mph on highways and expressways of similar construction and design as those in the city.

And the survey, as it has been pointed out, indicates t hat Sal Mineo got two speeding tickets, five minutes apart, on a network of roads—the West Side Highway and Henry Hudson Parkway—on which almost everyone does at least 10 mph over the speed limit, and is never bothered by police.

Sal Mineo indeed was unlucky to get nabbed twice in one day for what the cops have charged, in his case, was speeding.

But we wonder—would he have been stopped at all if his name wasn’t Sal Mineo?

Doing 54 or 53, we strongly doubt it.

We think Sal has gotten a bum deal.

—GEORGE CARPOZI, JR.

Sal’s in “Exodus,” U.A. and will soon be seen in “Escape from Zahrain,” Par.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1962