The Big Split-Up?—Dean Martin & Jerry Lewis

As this is written, the marriage of two of the greatest talents in show business is at stake. The headlines say theirs is now a marriage in name only—and in money only.

True, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis are now being held together by five million dollars and five years of contracts. Both Dean and Jerry have said they’ll fulfill all commitments and this is going to occupy them for quite some time. They may have a trial separation, but there could be no divorce. As one friend puts it, “It’s just mathematically impossible.”

A few months ago, they signed a contract with Paramount, which says they must make six pictures in the next five years for them and three pictures in the next three years for Hal Wallis, who releases pictures through Paramount. At the end of this time, each will receive $2,500,000 clear. They have a three-year contract with NBC, and they’ve signed for one year with Colgate, for whom their company, York Productions, is to produce thirty-nine “Sunday Hour” television shows beginning in September. And Dean and Jerry must star in five of them.

But they’re held together, too, by many more millions of fans. All ages. All nationalities. All religions. By many, many people who’d never heard of a place called Brown’s in the Catskill Mountains and to whom television ratings and contracts and the like couldn’t mean less. They just know that years ago they took to heart an hilarious clown with a cracked voice and a chrysanthemum haircut and a handsome Italian singer who browbeat him with affectionate despair. Together, Martin and Lewis make happy music and the public loves them that way.

And there’s also the matter of another “contract” between a Jewish boy from the borscht circuit, Joseph Levitch, and an Italian barber’s son, Dino Crocetti, who married their two un-likely talents ten years ago for richer or poorer and for better or for worse.

It’s sadly ironic now that they’ve never been richer and their relationship has never been for worse. It’s ironic that a long dispute over where the premiere of a picture would be held could be the crowning thing.

Those closest to Jerry and Dean waited out the final hours, watched an emotionally distraught Jerry board the train taking him East, and a calmer, but deeply hurt, Dean take to wings, putting a further 2500 miles of water between them. Until that last hour, it hadn’t seemed possible that one of them wouldn’t give. Once, this couldn’t have happened with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. Once, they wouldn’t have allowed the Catskill Mountains or anything else to come between them—whatever the circumstances or whoever the outside influences. That they finally did is a sobering thought to those who care for them.

A sad-voiced Dean, packing to leave that evening, put his thought into words when he told us, “If Jerry thought as much of me as he’s always said he does, he wouldn’t have done this.”

And in the dramatic setting of Brown’s Hotel in the Catskills, where he had bellhopped ten years before, a tearful Jerry indicated he felt Dean had really et him down. To a hushed audience, containing the nation’s press who’d made the junket for the premiere of “You’re Never Too Young,” Jerry signed off emotionally, thanking them and speaking haltingly of his “problem” and his “heavy heart” and “cross to bear.” It was sad and poignant watching half of the most famous team in show business carrying the show alone.

Those close to them are heavyhearted today. There were far more serious overtones involved here than a disagreement about where to hold their movie premiere. This was straining a sensitive situation, widening a wound already almost beyond repair.

It’s no secret that Dean Martin has long believed, and with reason, that some shortsighted people have belittled his talent and his importance in the team. Today, Dean feels that Jerry, too, considers his a secondary role.

Although it never reached print, where they would premiere their picture had been under dispute for months prior to departure time. From the time, in fact, when Jerry’s old bosses at Brown’s Hotel offered to pick up the tab for the whole press junket if “You’re Never Too Young” could be premiered there. To the studio, this sounded not only like a fine publicity gimmick; it would save money, too. With his loyalty to those who’ve helped him in the past, Jerry Lewis fell in love with the idea. Under a mistaken impression that Dean had agreed to the arrangement, Jerry threw his whole heart into going back where he began. Plans began to shake, rattle and roll before those concerned realized how strongly Dean opposed premiering the picture there.

“I never did say I would go to Brown’s.” a serious-voiced Dean says now. “If I had, I’d have been there. For four months I’d been saying I wouldn’t go.”

Since this was their own York Production and Dean was a full partner, he felt he had a full vote about where their picture would be premiered. The fact that this would be a free ride shouldn’t, he felt, be an influencing factor. “When our company spends two million six hundred thousand dollars on a picture—which I think is too much—you don’t have to pinch for a premiere.

“I told them from the beginning I didn’t want to have the premiere there. Jerry was a little upset. ‘Let’s take it to Steubenville, Ohio, then, your home town,’ he said. I told him I didn’t want to take it to Steubenville, my home town. ‘Let’s take it to a nice neutral place—like we did last year. There are many neutral places to go.’

“We’ve always made our plans together. We’ve always talked it over and agreed to go here or there. This is the first time in nine years I’ve ever really asked Jerry to do one thing. I said, ‘Let’s not go to Brown’s’—and he turned me down. All I can say is he must have had some real obligation somewhere. He must have had his own reasons to do this—reasons he didn’t tell me.”

Jerry, on the other hand, couldn’t understand why Dean wouldn’t go along with him on this. At one time they decided to call off the premiere. Then Jerry was hurt.

To those who’ve stressed the fact that money will hold them together, no matter what, an unhappy Jerry said, “This matter goes beyond money. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a matter of the heart. No amount of money can make up for a feeling of the heart.” With Dean, the matter went beyond money, too. It’s a matter of heart with him, too—and of his own self-respect. He knew the criticism he was inviting by not going. He knew what eventually happened would happen. That he would be the heavy in the eyes of the press assembled there. If Dean Martin hadn’t been so emotionally involved himself, obviously he would have gone. The smartest thing to do was to reverse his decision and appear.

“But I said something and I meant it. It’s our picture and I was wrong in not helping publicize it,” said Dean slowly. “But I said too many times I wouldn’t go. I had to take a stand and I took it. And I can’t lie to myself. My word to myself—that’s important, too.”

He dismisses any allegations of jealousy with, “Jealous of Jerr? If I were jealous of Jerry, we wouldn’t have been together more than two years,” he says in reference to the lines, the footage, the publicity et al. that overshadowed his own.

“We mended last year’s rift when Jerry and I sat down and figured things out,” Dean said. That argument began with Dean’s role—or no role—in “Three Ring Circus,” but it mushroomed into many other things. “There was no sense in me being in that picture at all,” Dean said. “The picture was on thirty-five minutes before I sang one song. Then it was an old one, ‘It’s a Big, Wide, Wonderful World, and I sang it to animals.” Sad irony that the death of Patti Lewis’ mother, at the height of the discord, helped in pulling them closer together then. Dean and Jeanne stood by through a difficult time, and when they got out on the road tour, away from various disturbing elements, Dean and Jerry locked themselves in a room and thrashed it out. Three hours later, they emerged a team. And Jerry felt so strongly about it that he banned forever a magazine which had blamed Dean.

It would be a major operation—separating them. They’re big business today. The biggest. And for harmony’s sake, there are too many interested parties involved. Too many professional in-laws. So many, that when there’s a meeting of the clan for a conference, they don’t know whether to hold it at Music Corporation of America’s gigantic suite or the UN.

That their show has gone on in spite of all the in-laws and outside influences is tribute to both of them. But two such opposites—he handsome pipe-puffing, casual Dean and the heart-tugging, emotional Jerry—can provide strain. Dean isn’t geared to match moods and emotions with Jerry. There’s the fact, too, that Jerry is nine years younger and an eager beaver consumed with show business, while Dean wants to slow down and live a little along the way—enjoy—s new home in Beverly Hills and his family. Dean’s all for getting the job done, but less feverishly. He’s been wanting to cut down on personal appearances and night-club dates and commitments for some time.

But the heart of today’s difficulty is Dean’s sincere belief that Jerry’s “generaling” the team. He acknowledges that in the beginning he was helpful in bringing this about by leaving many of the decisions up to Jerry. But today, in his opinion, the situation’s gotten well out of hand.

“I know this is partly my fault. I let Jerry take over these things, but I let him do this, too, because he’s happier when he does. He’s made that way,” Dean says quietly, in much the tone of the big brother Jerry used to claim him for.

“Jerry’s a great talent, but he wants to direct and produce and write. He worries about the whole show. About blacking out the shots, the costumes, the scripts, the directions—everything. I don’t think this is necessary. If he’d just let producers produce and directors direct and writers write, he wouldn’t have to do all these things and he could just concentrate on being one hundred per cent funny, which is a tough enough job.”

Those closest to Jerry say he’s worried a great deal, too, about making sure Dean’s part is right in the show. That he’s fought for Dean more times than Dean can know. A television associate recalls the countless times Jerry’s sent back TV scripts saying, “Not enough for Dean.” There are so many wonderful pantomime things Jerry could do, but he can’t do them working as a team. And he won’t do them because there’s not enough in them for Dean.

Jerry would be very happy if Dean would take a more active part in the show, it has been said. If he would come to their meetings, instead of spending so much time on the golf greens.

“I only play golf when I can,” Dean says now. “When there’s work to do, I’ll do it. When there’s a tv rehearsal and we can get down to the business of rehearsing—I’ll do that.”

During a rehearsal for their last television show, Dean made his entrance on-stage on cue and couldn’t find his partner anywhere. “I asked where he was—and Jerry answered me, ‘I’m up here, Dean—lining up the shot,’ he said. “You do the walk-ins and ad lib and we’ll do the dialog later.’ What’s with this? Me do the walk-ins and we’ll rehearse later. I’ll rehearse when we’re ready to rehearse the way it should be done,” he says, of a number of quips in gossip columns saying he ducked rehearsals on their TV show.

According to one member of the cast, something similar occurred when Dean showed up for the first day’s rehearsal right on schedule. At eleven o’clock Jerry still was nowhere around.

“Where’s Jerry?” he asked.

“Oh, Jerry had things to do,” one of the production staff said. Adding, “Come back around three.”

“Come back around three? See you tomorrow,” Dean said, script under his arm and walking away.

“Hey, wait, you can’t do that.”

“You let me worry about that,” said Dean.

To Dean Martin it seemed that Jerry Lewis is too busy being producer, director and writer to have time to be a team.

To the surprise of a good many people, the television show went on, although the tension was so thick off-cameras it seemed bound to show on the Tv screens. Tension had been build- ing all week between the two and reached fortissimo around curtain time. “We just can’t work this way. We can’t do it unless we love each other,” Jerry said. “Yes, we can. We got a job to do,” said Dean.

In living rooms across the land, those laughing at the hilarious take-off of Edward R. Murrow’s “Person to Person” and the rest of the show couldn’t know the drama of the moment— couldn’t know that this show might well be deciding the future of Martin and Lewis as a team. Could they make the same happy music together—if the heart should wear thin? It was with mixed emotions those close to them conceded—along with the smash reviews—that this was the season’s best show. They could do it the hard way if need be.

Certainly during the past year the show’s gone on for them more than their public can know. And when the chips are down—their loyalty shows. The show has gone on under every conceivable situation. Drama, illness, tragedy and discord. They’ve weathered them all.

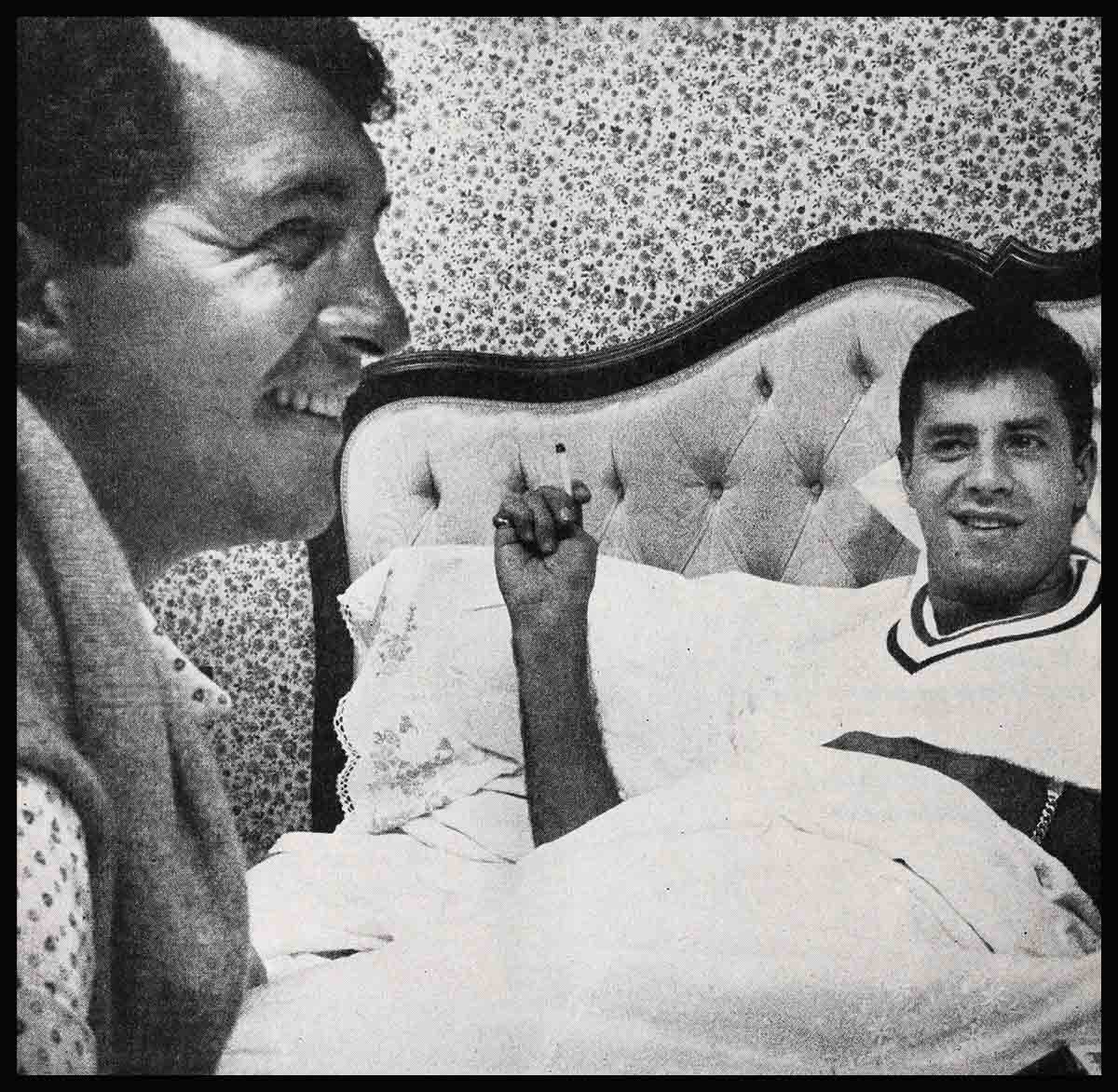

When Jerry became ill a few hours before they were to open at the Mocambo, Dean carried the show alone. “I was scared stiff, but Jerry had one hundred four degree fever. I had to go on.” Dean had rushed out to Jerry’s home as soon as he heard the news. Dean took one look at Jerry and said, “You stay right there. It will be all right—I hope.”

That evening Dean looked around him at the star-studded, jammed night club and said, “I wouldn’t give this spot to the cleaners.” But he was a smash, and some of the greatest names in show business helped pitch in. Jerry sent him a wire. “Do you know how great we were last night? We were wonderful. Thank you. Your partner.” Jerry, it developed, had jaundice. During the long weeks when a restless Jerry lay there counting the hours. Dean would pop by with a bit like throwing his laundry on the bed and saying, “Have it back by Friday—no starch.”

And the show’s gone on—when there’ve been personal difficulties.

When Jerry’s pattern for living, for surrounding himself with crowds that constantly cluttered up their home got too much for Patti the past year, she told Jerry sadly one day she just couldn’t go on. Patti knows now she couldn’t have gone through with it. As she’s said, “This is it—I know.” But that day their marriage seemed over for her. She felt she had to talk it over with somebody. Somebody close to them, who’d known them through the years. With Jerry’s knowledge, she decided to talk it over with Dean. She called Dean and they met at the Rivera Club one afternoon. She told him she was unhappy and why, ex-plaining she just couldn’t seem to get through to Jerry anymore and there were too many people always around, in-between. Dean talked to Jerry and he got through. He pulled no punches and helped straighten out their marriage. And Jerry was grateful. “Honey—I’ve just never realized. Dean’s so smart.”

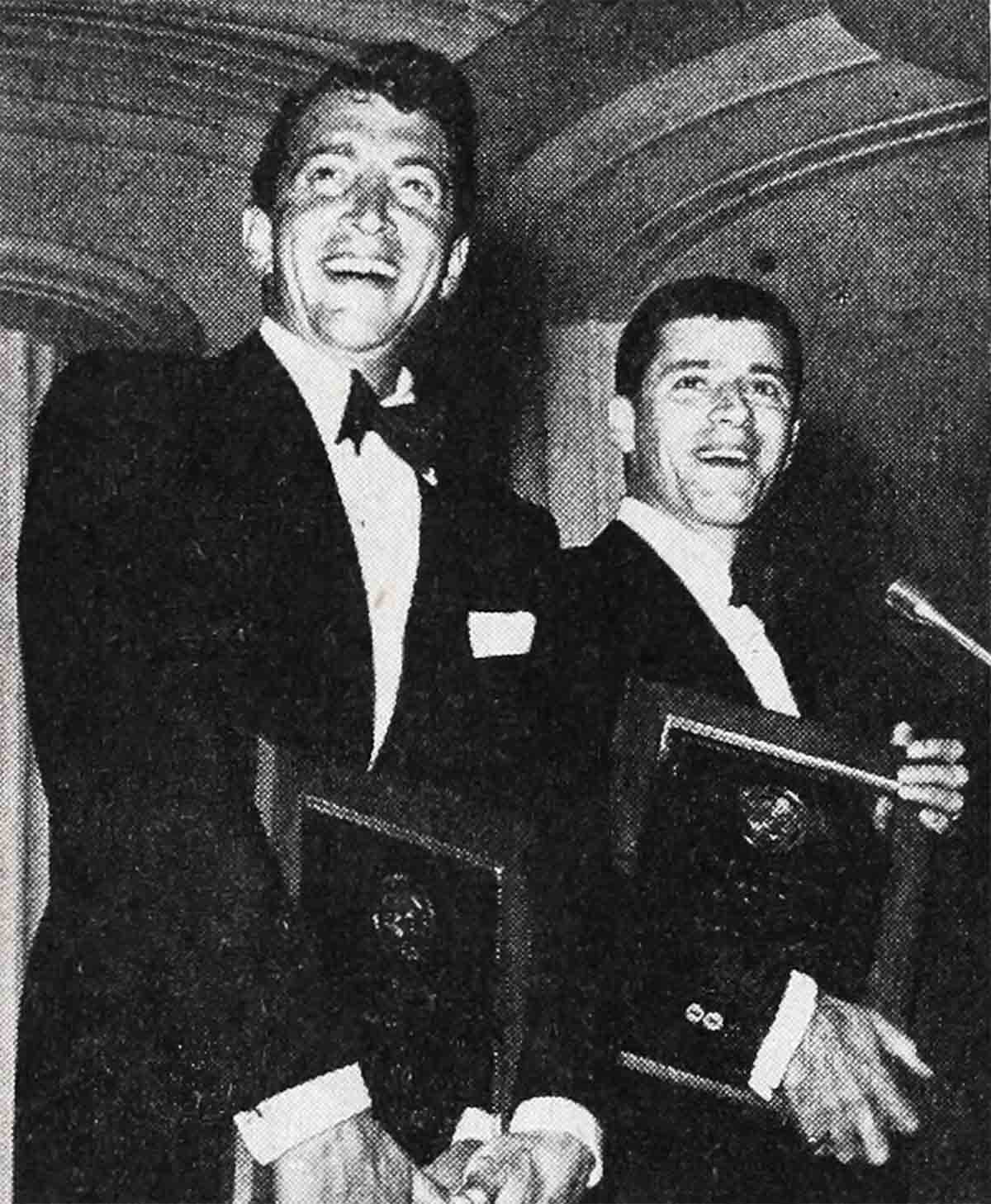

And there’s the charity benefit recently, when Jerry swallowed anger and resentment to help Dean with the show. It was a benefit put on by Share, Inc., a club of movie wives, for an exceptional children’s fund. Dean’s wife, Jeannie, is very active in the club and Dean was emceeing the show. Because the team’s ex-manager, who’d once sued them and with whom Jerry has a long-standing personal grievance, would be there, Jerry decided not to go. That Dean still associates with the manager has been a sore point with Jerry and still is. But at the last moment, when Dean was on-stage emceeing, Jerry walked in. And again—the show went on.

The show went on—at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas—a few months ago when Jerry’s cousin, Judy, the nearest thing to a sister to him, was murdered by some muggs. When Dean and Jerry played the Copa shortly before, Judy had been ringside, grew misty-eyed over their soft-shoe “Every Street’s a Boulevard.” Just two weeks before, Jerry and Patti had visited her in New Jersey. For hours after getting the news, Jerry was in a state of shock. Then he got out some pictures he’d just made of her and began to cry.

The crowd in the Sands’ lush Copa Room will never know what a show Martin and Lewis gave that night. For those close to them, it’s one always to remember. How they heckled and badgered and gagged through their “lunatic and lover” routines. And how Dean, ever watching Jerry, moved in close when they started the soft-shoe on “Every Street’s a Boulevard.”

They have three more years’ dates at the Sands, too.

In spite of commentators’ flashes that the two are talking about going out on their own, their show may go on and on.

It will go on—for seven more years anyway. “This is no split-up. People have gotten the wrong idea,” Dean says seriously now. “There’s no possibility of us splitting up now. I have seven more years at Paramount. We’ll do the Colgate Television show this year. And the next—I’ll have a little singin’ show of my own on NBC. We have commitments and I’m going to fill them. I have to—and I want to.”

There’s a matter of money. But for Martin and Lewis there’s also a matter of heart. Miles and miles and miles of heart.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955