Marilyn Monroe In The House

If, some cold and snowy winter night, your husband called you from Hollywood to say, “I’m bringing Marilyn Monroe home with me. She’s going to stay a while,” what would you do?

By now, nearly everyone knows what Amy Greene, wife of the gifted magazine photographer Milton Greene, did. In the chill of the 5:00 a.m. December darkness, she wheeled out the family station wagon, drove fifty miles over roads which wind in sharp curves around forested, rocky bluffs, met the two at La Guardia airport and secretly whisked them home. Welcomed to the security of the Greenes’ place deep in the Connecticut hills, Marilyn was safe—hidden away from people who demanded to know each heart-wrenching detail of her breakup with Joe DiMaggio.

For the first time in a turbulent life, which has held both unusual hardship and outstanding success, Marilyn Monroe, in the undemanding privacy of a happy home, was able to enjoy the luxury of taking time out for her own relaxation.

As word got around that the curvaceous blond who has become the very symbol of sexy allure was their houseguest, Amy Greene caught a barrage of feminine questions and advice. Some of the women were subtle, some outspoken, but whatever their manner, it all boiled down to one inevitable pronouncement: “Now I know you and Milton are devoted to each other, but if it were I . . . well, I don’t know. I’m not sure I’d risk having all that glamour under my own roof for weeks at a time.”

Today, Amy has a crisp summary of that attitude. “They must have thought Marilyn was a combination of Theda Bara and Mata Hari—the vamp and the threat.”

Unruffled, Amy then replied to her would-be advisors with a wise little smile. “You’ll like her, too,” she predicted.

As the Greenes continued their usual practice of holding open house for their friends each weekend, Amy had the satisfaction of having women follow her to the kitchen to whisper, with an air of surprised discovery, “Why, I like Marilyn. She’s nice.”

But the questions flared anew, and they came this time from women all over the nation when, on Edward R. Murrow’s TV program, “Person to Person,” viewers glimpsed the three around the fireside, heard Marilyn call the Greenes’ house “home,” heard Milton speak of Marilyn Monroe Productions, of which she is president and Milton vice president, and heard Amy say, “Marilyn is the ideal houseguest.”

To understand Amy’s answers and her attitude, one must know a bit more about Amy Greene herself. Amy Greene is an almost incredible combination of youth and maturity. Slender, tiny—not quite five feet tall—she looks about fifteen years old. A sprinkle of freckles dusts her gold-tanned face. She wears no make-up, not even lipstick. “Milton asked me not to. So I haven’t had lipstick on from the day we were married until the night of the Murrow show. I had to use it then.”

While she looks like a child, her quick actions, crisp speech and well-formulated observations have the sureness of an intelligent woman who has thought things through, knows who she is, what she wants out of life, and is extremely happy with the situation in which she finds herself.

This situation includes a close family relationship. In nearby Westport, Amy is likely to lunch at The Daily Corner, a charming little restaurant owned by Milton’s sister, Heny, and his brother Harold. There, Amy may chat with Harold’s wife, Bea, over tasty hero sandwiches, delicious coffee and homemade chocolate eclairs.

Mrs. Franco, her mother, lives with Amy and Milton and is a gracious, quiet woman. Josh, her son, is a robust, beautiful child with dark curly hair, deep velvety brown eyes and long, long lashes. At fourteen months he is enthusiastically experimenting with walking and talking. “I do believe he misses Marilyn,” Amy explains, “now that she comes out from New York only occasionally. She’s wonderful with Josh. Helps me feed and bathe him and, if the rest of us are busy, she’s always down on the floor playing with him. She even stayed home to baby sit on Christmas and New Year’s so the rest of us could go out.”

There are many indications of a confident, affectionate partnership between husband and wife which are borne out by Amy’s own statement, “I’m a very secure person,” the answer to that question which so many women have asked, “How could any wife welcome an actress who, to most Americans, personifies irresistible magnetic attraction?” It simply adds up to this: The Greenes, together, could offer Marilyn—or any other friend—a tranquil refuge in a troubled time because they, themselves, have found an emotional unity.

Even the structure and plan of their home confirms their happy partnership. Theirs is not such a house as you can buy, ready-made, in the nearest subdivision. Theirs has required from both Milton and Amy an artist’s perceptive eye, an architect’s and decorator’s skill and much hard do-it-yourself labor.

In an eleven-acre tract, the house, which now has sixteen rooms, stands at the crest of a hill. There’s a wide, tree-shaded lawn, and across the driveway, a vegetable garden. At the back there is a stretch of wild woodland.

Amy told its history and pointed out landmarks. “The original building, which is now our living room, stood halfway down the hill when Milton came out here nine years ago. It once was a stable. We found a date, 1746, carved into one of the heavy beams. See those two pear trees? That’s where we were married. September 13, 1952.

The spacious living room has the full two-story height of the old stable and its loft. The fireplace is huge and so are the custom-made sofas which flank it. A small plant-filled conservatory forms a passage-way to the sitting room (which was shown on television) and the big kitchen which is colonial in its arrangement and ultramodern in its appliances. Going on through the utility room, we came to Milton’s studio.

Reproductions of Milton’s photographs, the framed covers of famed magazines, deck the walls. Amy explained proudly, “He’s been a professional photographer since he was fourteen, and a successful one since he was twenty-one—virtually the boy-genius sort of thing.”

Among those pictures is an outstanding one of Marilyn Monroe—the picture which was the cause of their first meeting.

Amy told the story. Look had sent Milton to Hollywood. A writer from that staff, touring the studios with him, showed Marilyn a portfolio of his pictures. Instantly impressed, she had said, “These are the most beautiful pictures I have ever seen. Can you have this man photograph me?”

“That’s easy,” said the writer. “He’s right here,” and introduced Milton.

Marilyn’s eyes had widened. “But he’s just a boy!”

“You’re just a girl,” Milton had replied.

Amy, who was then in Connecticut preparing for their wedding, heard about it when Milton phoned that evening. “I photographed Marilyn Monroe today. We got along just fine.”

Amy, who through five years of modeling had well learned that inspired pictures result when the photographer and the subject like each other, then had other things on her mind. “That’s nice,” she had replied. “Some presents arrived.”

“You’ll meet her, too. You’ll become friends,” Milton predicted.

“I’m sure we will,” Amy had agreed, “but now about that caterer . . .”

Today she says, “It wasn’t until we got to Hollywood, during our honeymoon trip, that I remembered what he had said. Marilyn first came to our hotel to meet me. Then we saw her again at a party Betsy and Gene Kelly gave. We were all playing charades. It didn’t take long to see that Marilyn had wit and charm and intelligence as well as beauty. Milton was right. I did like her instantly. We did become friends. From then on, Marilyn had a standing invitation to our house.”

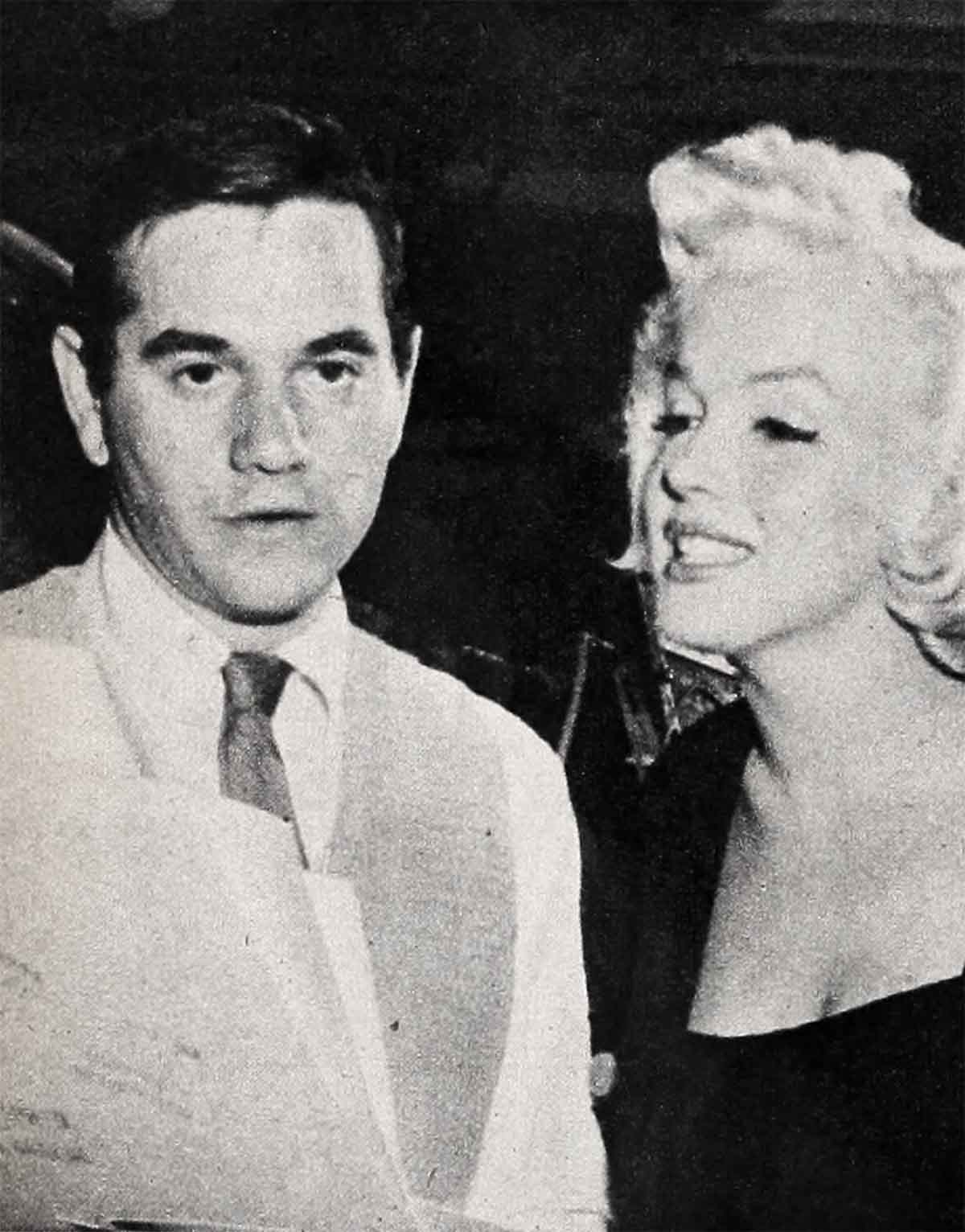

Last summer, filming of street scenes for “The Seven Year Itch” brought Marilyn to New York and they grew to know each other better. Marilyn asked the Greenes to accompany her to plays and night clubs.

Everywhere people clamored to see Marilyn. Amy remembers with amusement, “We were going back to the hotel, with Marilyn sitting between Milton and me in the taxi. In front of the hotel there was, what seemed to us, a crowd of at least five hundred people. Our driver turned around all excited. ‘You know who’s staying there? Marilyn Monroe! Gee, I hope I get to see her.’ ”

The New York trip was a great triumph, but a tragic time was to follow. “Milton was on this coast when Marilyn and Joe broke up,” related Amy. “You know how dreadful that was for her. Of course we wanted Marilyn to know that we’d be glad to help in any way possible.”

When, as it turned out, the privacy they could offer was the thing most useful to exhausted Marilyn, Amy, for her own sake, was delighted.

“I thought it was just great that she could come to visit us. It would be nice to have a girl around the house. I grew up in boarding schools and, although we have lots of friends, there’s just so much distance and we’re all so busy that I don’t get much chance to sit down to talk with other women. I miss it, too.”

In typically feminine fashion, their talk fests went on for hours. “We’d discuss everything from clothes to housekeeping to babies to headlines. Sometimes we’d giggle like a couple of school kids. Others, we’d come up with some sure-fire formula for saving the world. You know the way women do.”

Marilyn adjusted effortlessly to the routine of the household. Says Amy, “She made her own bed, kept her room tidy, brought down her clothes on washday. If she slept late, she would make her own breakfast, rinse off the dishes and put them in the dishwasher. Neither Sadie, our maid, nor I had to wait on her.”

She fulfilled a further requirement of a good guest by never expecting her hostess to provide a continuous round of entertainment. “Marilyn is always reading and few people realize how much serious reading she does. And she loves to walk. She’d bundle up in some of Milton’s outdoor clothes, call the dogs and tramp out through the woods.”

The wintry Connecticut countryside was a source of continuous wonder. “Marilyn had never seen snow before, nor known cold weather. She, too, likes to drive. We’d take the convertible, and with the top down, we’d go sailing along the highway. We both liked to feel the wind on our faces and the warmth of the heater on our legs.”

Spring, when it came, was another surprise. “I remember one day we were driving home from a friend’s house. Marilyn looked up at the hillside and remarked that the trees were just dead, bare sticks. Then, the next week, they began to turn green. To her, it seemed a miracle.”

But most important of all, to Marilyn, was the fact no one bothered her. She could go about unnoticed, wrapped in an old polo coat and without make-up. No prying, no questioning, no demands. Once in a while a neighbor’s child would ask Amy to get an autograph, but, Amy points out, “They were always polite about it.”

The easy, informal country entertaining also pleased her. Amy says, “A lot of people in show business and advertising and publishing live up here and she was just one of us. At a party she never sat in a corner playing regal and expecting guests to come to her. More likely, I’d find her emptying ash trays or picking up glasses. If someone went to the piano and she felt

like singing, she’d sing. And she knows how to listen, that girl. To women as well as to men. It didn’t take the girls long to see that Marilyn wasn’t after anyone’s husband. She just simply fit into our crowd and everyone loves her.”

As rest, peace and sharing the everyday happiness of the Greenes’ life restored her spirit, Marilyn’s great vitality surged back and her thoughts turned to the future. With Milton’s help, she organized Marilyn Monroe Productions. Amy says, “Almost every evening there were meetings with the attorneys. Milton says Marilyn has a good understanding of business, but I wouldn’t know. I’d just get out of the room.”

Another phase of her career had, however, obviously been the topic of many a conversation.

Amy told how Marilyn, on moving into a New York hotel suite, laid out a schedule of study. Several days each week she goes “as an observer” to classes at the Actors Studio where carefully selected, talented professionals work with famed directors. She also works with a private drama coach.

While Marilyn has been most modest in speaking of this program of study, Amy had the conviction of a close friend who believes in another’s talent. “Marilyn is more than just a glamour girl. When they see ‘The Seven Year Itch,’ I think a lot of people will realize she also is a good comedienne. But she wants to be a better one. She’s serious about her studying and, here in New York, she has a new opportunity to seek out people who can teach her more about the theatre.”

To work and study, Marilyn was soon able to add a third essential for happy living—fun. She charmed the New York show business crowd—which can be standoffish—and, when she was ready for them, there were many invitations.

Says Amy, “I didn’t realize how much she really loves people until we started going out around New York. That magnetism, believe me, is a two-way current.”

Amy’s first experience with it overwhelmed her. They went to the Copa to hear Frank Sinatra. He invited them to come back to his dressing room. “It seemed to me most of the audience decided to go along. The passageway wasn’t built for mass movement. At the steps there was a terrible jam.”

Almost smothered, five-foot-tall Amy grew panicky. “Marilyn calmed me down. She spoke directly into my ear and reminded me that the bouncer, who was leading the way, was a big strong, husky man who weighed at least two hundred pounds. She told me to put my arms around his neck and hang on. He would take care of me, and Milton, who was fighting sort of a rear guard action, would take care of her. But it was the most amazing thing. In all that pushing and shoving, Marilyn kept on smiling and talking to people. She wasn’t scared a bit.”

Marilyn’s confident feeling about crowds, she later told Amy, had its source in her first real encounter with them during her tour of Korea. Standing on a flimsy platform, she saw the troops break ranks. As they moved down hill, it seemed as though the hill itself were moving. “Marilyn did the only thing she could do,” says Amy. “She took the microphone and asked everyone to sit down so they could go on with the show. It was sufficient to get the situation under control. Now, she simply says, ‘No one wants to hurt me.’ When we’re in a crowd, it’s me she worries about.” She’s always asking Milton, “Is Amy all right?”

Going to the theatre with Marilyn is, Amy reports, a show in itself. “Between acts, everyone talks to her. People will call down from the balcony to say they either like her dress or that they don’t like it. Or that her hair looks lovely. Or that they have enjoyed her pictures. And she answers them just as though she had known each one, personally, all her life.”

The most thrilling of all her appearances was opening night at the circus—a benefit for the Arthritis and Rheumatism Foundation. Milton Berle was ringmaster and Marilyn rode a pink elephant. Amy recalls, “Everyone cheered her and, when I looked up toward the balcony, it was the strangest sight. All I could see were open mouths, right up to the rafters.

With such receptions, it is small wonder that Marilyn has said repeatedly that she loves New York. “She’s looking for an apartment here,” Amy confirms. “And she’ll always have a second home at our house. We did the guest room over for her. It’s in purple, pink and white. The curtains and dust ruffles are crisp white organdy. The wallpaper is lavender with a small purple figure and the rug just matches that purple. There’s a pink quilted bedspread and dark purple velvet throw pillows. The chest is an old one with a white marble top and I put pink china lamps on it. It’s a simple and sort of old-fashioned room, but it is dainty as she is and suits her exactly. Marilyn loves it.”

And what about Marilyn’s future? Amy makes it clear that it is not hers either to announce or predict.

Professionally, however, it is apparent that a new phase of Marilyn’s career opened with “The Seven Year Itch.” Even critics who have, in the past, been somewhat acid about her acting now praise her as a comedienne. She’s deft, she’s subtle, she here reveals she has a true gift for comedy. As Amy says tersely, “She’s great.”

And her private life? Again, neither Amy nor anyone else close to her is, at this moment, making any statements. It is axiomatic, however, that nothing can put a woman into so domestic and romantic a frame of mind as a visit to a happy home where husband and wife have achieved the kind of affectionate working partnership one finds at the Greenes’.

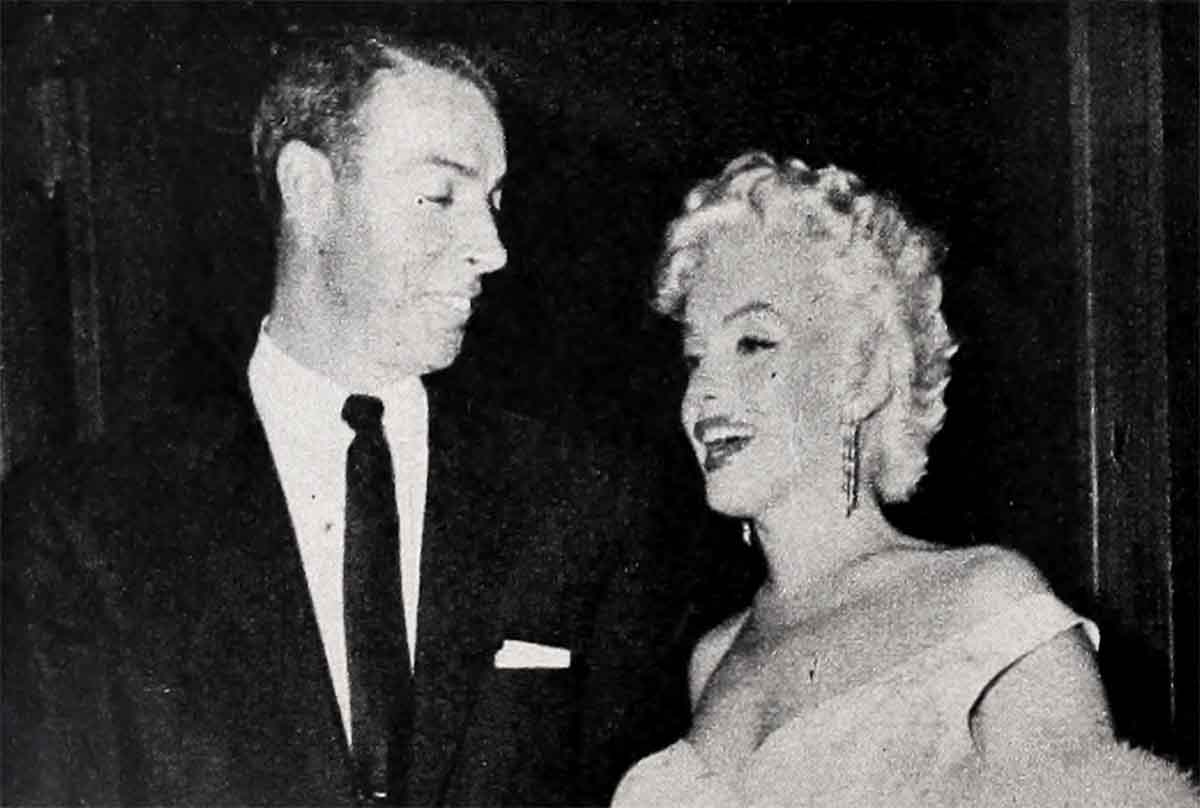

And Joe DiMaggio did escort Marilyn to the New York preview of the picture and afterward gave her a birthday party. What’s more, he looked ecstatically happy while doing it. Who can tell what happens next? As the fans say, “They look just like lovebirds.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1955