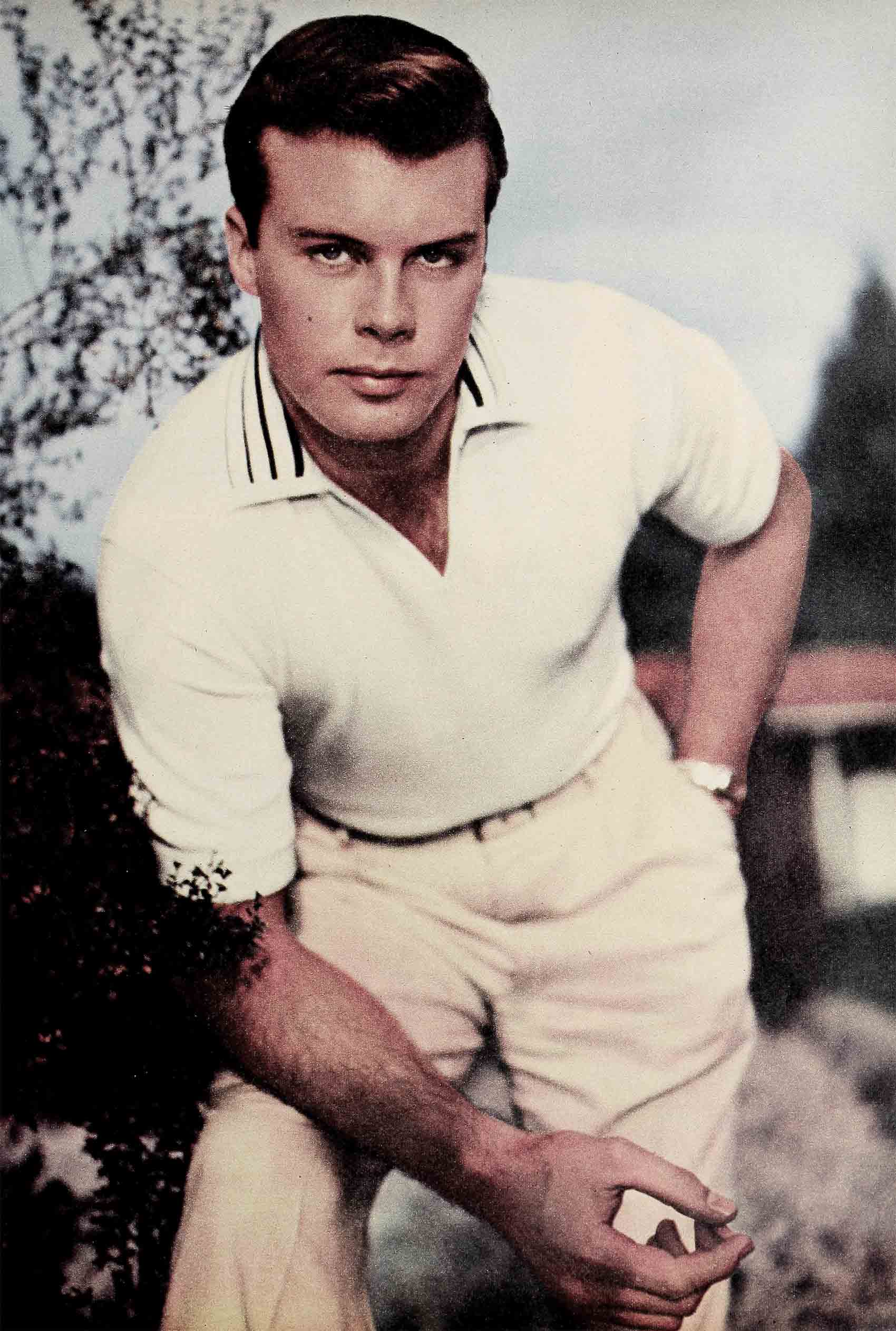

So Little Time—Bob Francis

Once upon a time, when there was such a thing in his life, Bob Francis would wake at odd hours, mostly late ones, idly contemplate the sky through his window and dally with the pleasing problem of how his day should be spent.

Currently, he scorches out of his bunk soon after five A.M., stumbles into and out of the shower, yanks on his clothes and falls into the driver’s seat of his secondhand Cadillac. All this is accomplished with the aid of one eye, as the other one stays stubbornly closed trying to grab an extra few moments of precious sleep. There is no time these days to contemplate the sky; in fact there is no time even to glance out the window, and often Bob has burst out the front door to find to his astonishment that he is being belted with buckets of California dew.

There is no longer any opportunity to sketch his days at will; they come tumbling at him, spilling over with things to do, with a regularity that keeps him spinning. Because Bob Francis is on the treadmill that comes to every actor who finds success in Hollywood. For the average actors, those who have worked their way up via the accepted routine of drama school, Little Theatre, radio and television, it is bewildering enough. But Bob landed the plum role of Willie Keith in The Caine Mutiny without so much background as a school play. There had been five years of dramatics lessons, true, but dramatics lessons per se don’t prepare anyone for the deluge of extracurricular duties of being a Hollywood star.

Along with acting in that first picture, in which he was a novice lined up with established talent such as Bogart, Ferrer and MacMurray, Bob had a few more things to learn, How to pose for still pictures. What not to say on an interview. How to meet countless people in jobs related to the industry and not forget their names. How to behave on the radio and television. How to remember everything that ever happened to him and hoard the anecdotes for distribution to the press. How to be polite to autograph hunter (even when they tore his clothes off).

No mistakes are allowed in these matters and there was no one to call on for help. Not the least of his problems was how to squeeze a week’s work into one day.

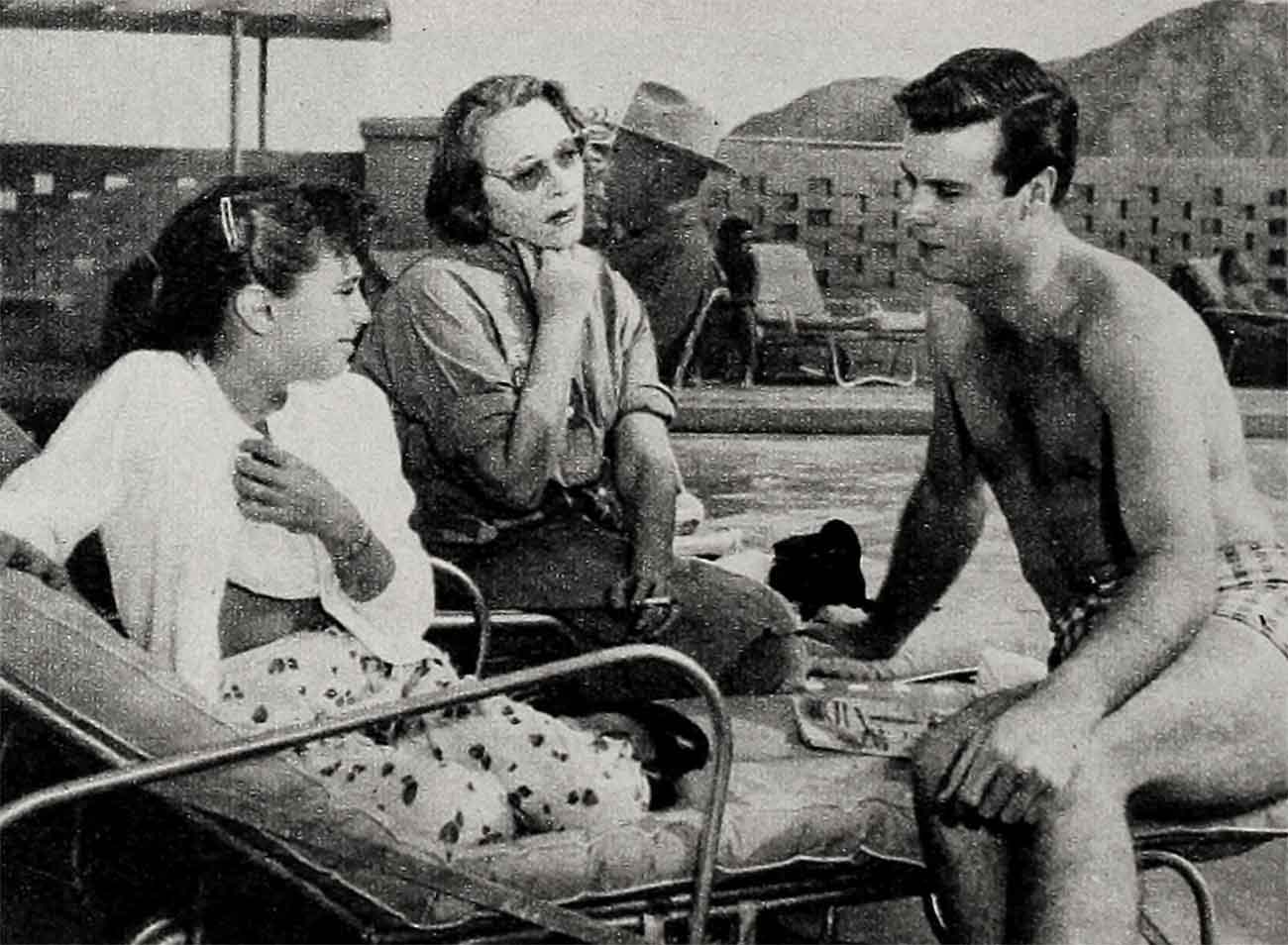

The Caine Mutiny brought with it Bob’s first trip inside a studio, but he didn’t have much time to look around. He learned quickly but painfully. One day a studio publicist brought Bob face to face with his first editor. One of the most mannerly young men in all of Hollywood, Robert greeted the man politely, indulged in a brief conversation, and disappeared. The publicist cast a frantic eye over the set and finally spotted him, tucked away in a corner talking to Rosemary Bowe. Buttonholing him, she ladled out the necessary lecture.

“Son, listen to me. That man is an editor. E-D-I-T-O-R. When you meet an editor, you don’t wander off. You stay with him for as long as he wants to stay with you. He is an important man. We want him to get to know you.”

“Oh,” mumbled Bob. “Sorry.”

“His circulation,” continued the publicist, “is one million, two hundred and one thousand copies per month.”

“Yes, ma’am,” said Bob.

In addition to burying such required information in his head, Bob accomplished his basic job—he delivered a polished performance in his first film. Then he was sent on a tour to publicize the picture. And another. And another. Then he made They Rode West and followed it with a tour. The Long Gray Line followed that, then The Bamboo Prison and still another tour. In less than a year, Bob made four movies and spent six months on the road—a phenomenal amount of activity for one single solitary human being.

But he learned. He found that a live audience didn’t frighten him at all and he wondered why. Then he remembered that the Army had broken him in for it. Sent to Camp Roberts after his induction in 1950, Bob had the task of explaining the Army to all new men. “When you have to stand up in front of 2,000 guys who’ve been in the Army for four days and tell them why they’re in the Army, you can handle any audience. You get so you’re even prepared to dodge the tomatoes.”

In public appearances he learned to turn tactless questions aside gracefully and even to get some interesting answers from the people he met. In a Hartford theatre a little girl approached him and expressed her gratitude for his being there. She said it was such a thrill for her because Hartford seldom saw celebrities. Bob smiled and thanked her, and carried the conversation according to Hoyle and Hollywood by asking what her father did for a living.

“Daddy?” said the youngster in an offhand fashion. “Oh, he’s the Governor.”

The son of solid, middle-class parents, Bob had never met anybody more important than his college professors. When suddenly he was thrown in with the elite of every city and state he visited, he thanked Providence that his parents had always insisted on his being a gentleman. Mayors and governors joined the parades in which he rode, and on one such parade, in Minneapolis, his poise left him for the first time. There were nine cars in the string, tearing triumphantly through the city with flags waving and sirens screaming. Bob was in the fifth car and as it sped around a corner following the others, the siren died agonizingly and ‘they found themselves suddenly stopped, bumper to bumper with the leading cars, which had turned into a dead-end street. It was an anticlimax that left everyone limp, not the least of whom was Bob, who flung savoir faireto the winds and collapsed in hysterics in the back seat.

He learned what it was to be dog-tired. He covered a city a day for seventeen days and soon found that except for noteworthy happenings that made him remember a city with clarity, most of them merged in his mind so that he couldn’t remember them separately at all. He was in constant danger of telling the people in, for instance, Columbus how much he liked Toledo, and had to keep reminding himself what city he was in. Travel had been one of Bob’s dreams and these trips were his first sight of most of the cities, and yet there was never time to see all he had wanted to see. In New York he went for a long walk beginning at five A.M., the only time he could squeeze out of his schedule to see Manhattan alone. The next morning, same hour, he bought roast beef sandwiches and coffee in a delicatessen and took a ride in a hansom cab.

He found that poise is a prime requisite of a Hollywood actor, for as such he collided with strange situations and people.

Outside a Providence theatre a crowd was held back by a rope as Bob passed, but when a knee-high boy held a paper and pencil high and squeaked that he would like an autograph, the mob acted as if on signal and surged past the rope like a tidal wave. The child went under like a stone, and Bob needed all his strength to rescue the boy from being trampled.

In New England, in zero weather, a press agent wanted May Wynn to stand on the sidewalk and sign autographs. It was not Bob’s place to interfere, and the only thing he could do was suggest that somebody get May some fur boots to keep her feet warm, but he seethed inside at the unnecessary hardship for May.

In a midwestern city, Bob finished his stint in a parade, replete with Governor, and was then offered a car to do some private sightseeing. He had been on the road less than a half hour when a policeman pulled him over to the curb.

“Let’s see your owner’s license,” said the cop.

Bob had no more idea on that than he had on the whereabouts of the Lost Chord, and said so.

“Where’d you get the car, bub?” said the officer.

“Why—I borrowed it.”

“Oh, you did, did you? Well, this car answers the description of a stolen car, and I’m going to take you in.”

It wasn’t until he got to a telephone and called city officials that he could convince the arm of the law of its mistake.

There were characters, too. In The Latin Quarter, a Boston nightclub, he was approached by a young man inquiring if he wasn’t Robert Francis, the actor.

“Yes, I am,” said Bob.

“Well. I just wanted to tell you how much I liked that scene in The Caine Mutiny. I thought it was swell. You know the one where you’re drilling on the field with the rest of the men and when the line turns left you make a mistake and turn right?”

The man began to laugh and Bob smiled uncertainly, recalling that although the incident is in the book, it hadn’t been in the movie. The man continued to laugh, slapping his thighs and dabbing the tears from his eyes. “That sure was a great scene!” he said at last. “Only the funny thing was, the theatre where I saw it had cut it out of the movie!”

The next morning at six A.M. the telephone next to his bed wakened Bob. The voice on the line belonged to the stranger of the night before.

“Is this Robert Wagner?” he said.

Bob rubbed his eyes. “Who?”

“Robert Wagner.”

“No,” said Bob.

“This isn’t Robert Wagner, the actor?”

“No, it isn’t,” yawned Bob.

There was a slight pause. “Well, are there any actors up there?”

Back home in Hollywood, Bob finds new situations even with old friends. Those in the skiing circle regard the field of acting as something foreign as the moon’s surface, but they are genuinely happy over Bob’s success and don’t hesitate to let him know it. There are others who don’t want to admit they are impressed, and so they treat his new venture with sarcasm. “I would have gone to see the picture,” they will laugh, “but I heard you weren’t very good in it so I didn’t bother.” The critics have said otherwise, so Bob is aware that these people expect him to have changed.

“It’s pretty crazy, the attitudes you bump into. And there’s no reason for it. Two years ago nobody wanted to meet me, and now the only reason they do is that they’ve seen my face on the screen. That’s all. They don’t know me and I’m the same person I was. It’s tough with friends because I can’t very well go up to them and say, ‘Look, I’m the same knothead you knew five years ago’—because I’d be the one bringing up the subject. If they treat this career sarcastically then there’s nothing I can do except go along with them.

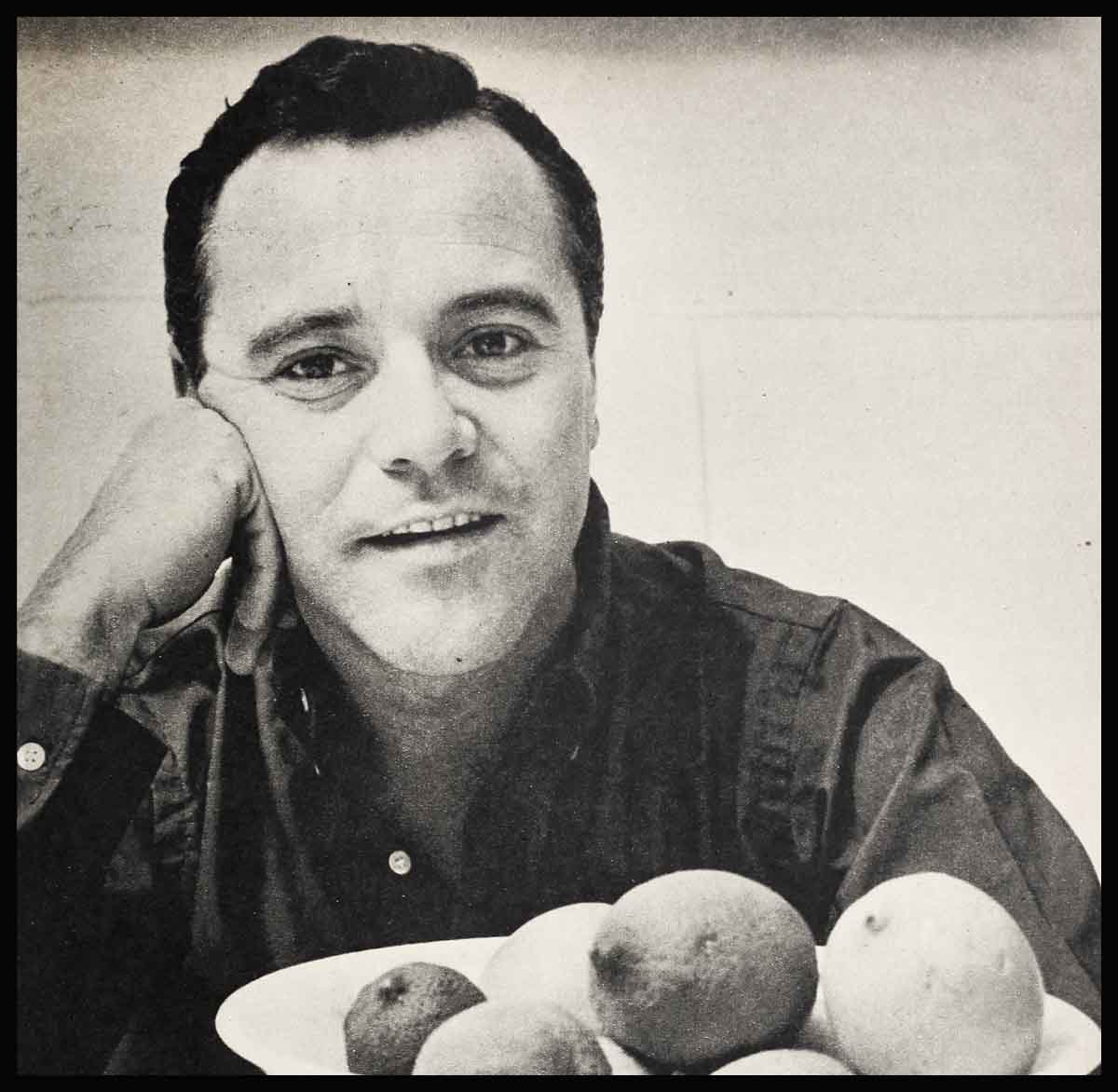

“I find interviews crazy, too, because what I have to say isn’t too interesting, and yet people want to know. Sometimes I think I ought, to wrap my car around a pole on my way to an interview so I’d have something to talk about. . . . It’s nice, of course, to be given good tables in restaurants and nightclubs, but it makes me wonder. Why should I have a better table than somebody else just because I’m recognized as an actor? When I went into the Pump Room in Chicago they ushered us to a table and two minutes later the headwaiter came over and begged my pardon and asked us to move to a better table. It’s embarrassing in a way.”

This attitude defines Bob’s modesty and levelheadedness. He is the product of parents who regard their three children with equal love and respect, and who are as excited about Bill’s success in business or Lillian’s family as they are about Bob’s acting. Bob’s own attitude toward his career is a happiness that he is doing something he enjoys and a prayer that he can go on succeeding.

It takes work. He spends about twenty-five hours a week in dramatics lessons, from both Benno and Batomi Schneider who have been coaching him all along. This is, of course, when he is in town and not working in a movie. “I like the life,” he says, “because there is no definite pattern. Patterns are awful; they give you a trapped feeling.”

That his days have no pattern is an understatement. When he came back from a long tour and had one day at home before he was scheduled to take off for a theatre managers’ convention, he was asked to. spend that day driving the 240 miles to and from San Diego where he judged a water skiing contest. The personal appearance tour for They Rode West delivered him back into Hollywood just two days before Christmas. He did all his holiday shopping the day before Christmas, towering over the mob scenes in department stores, and Christmas Eve he addressed and mailed his Christmas cards. People were wished a merry Christmas from Bob Francis on December 26, but then, everybody in town understands that he has less time to himself than a doctor in an epidemic of bubonic plague.

He would like to learn French and as a contractee at Columbia Pictures he has tutorage available to him, but not time. He would like to find an apartment closer to the studio, but there is no time to look for one. The reason he arises shortly after five A.M. is that he lives in his parents’ home in Pasadena, and as any Pasadenan knows, you have to leave the house by six A.M. if you expect to avoid the crush of the morning traffic into Los Angeles and Hollywood. As a matter of fact, Bob has been looking at apartments for a year now, but as soon as he finds one he likes he is off on another tour. “If I’d taken one last summer,” he says, “by the time I got to use it the year’s lease would have been up.”

He wants an apartment with one bedroom and contemporary furniture (“Old things depress me, and I want a place that’s bright and cheerful when I come home.”) and one of these days, with luck, he’ll be footloose long enough to find one. He wants time for romance, a thing which has necessarily gone by the boards (including his steady dates with Dorothy Ross) for lack of time. A guy can’t court a girl with any sort of regularity when he never knows which state of the Union his next meal is coming from. Currently he makes a date at the last minute when an evening is sure to be his very own, and as of the moment has no special interest in any girl. When he’s more certain of his career he hopes to get married, and when things have settled down he hopes again to own a ski shop.

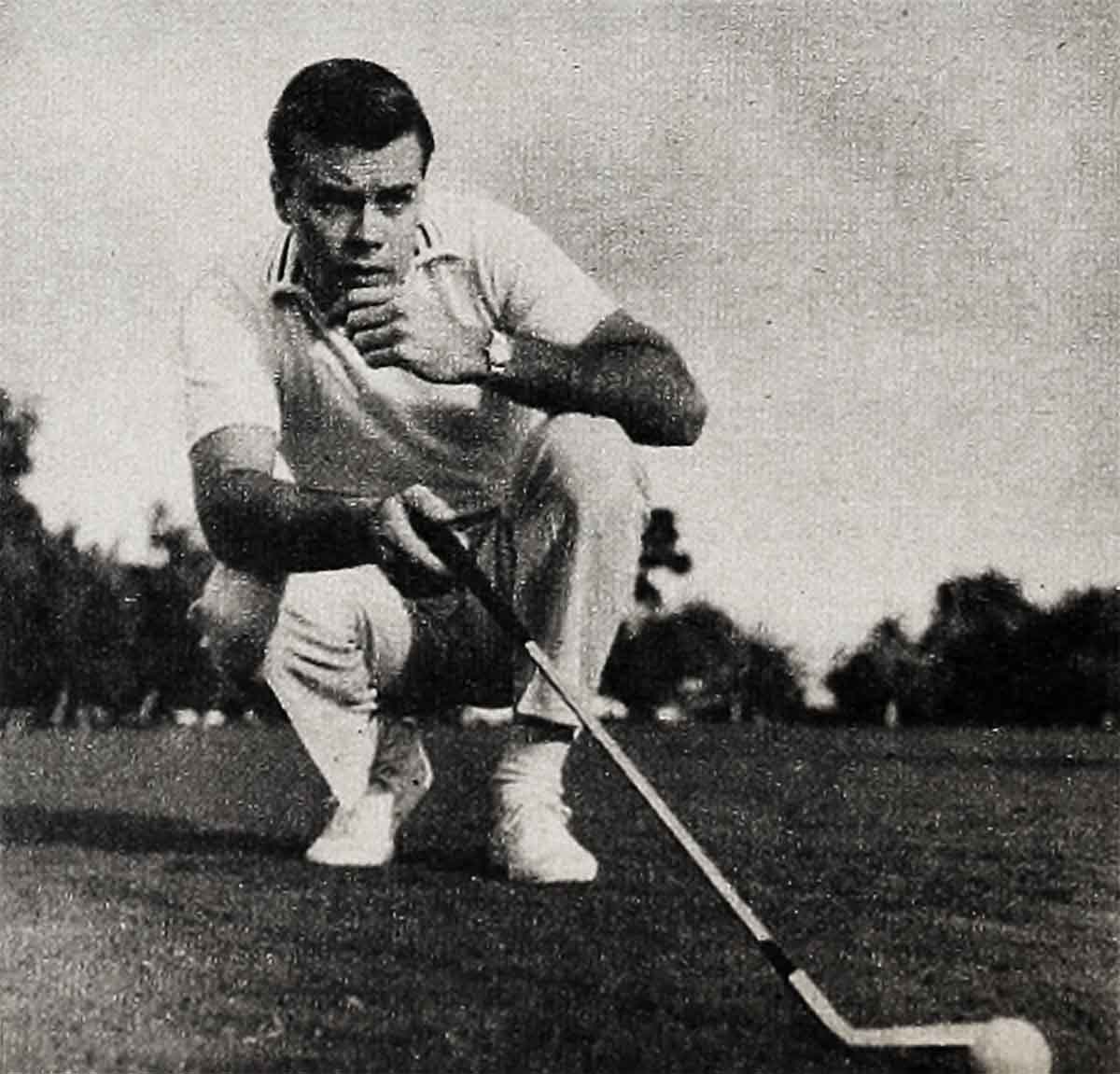

These two things, skiing and acting, are closest to his heart, and both have claimed him as an addict through his own persistence. The first time he skied he was eleven years old and tried it to please his brother. He didn’t like it at first—he fell down and got tangled up and disgusted, and when he realized skiing presents a challenge he made up his mind to conquer it. By the time he was seventeen he was in the tournament class. As for acting, when the talent scout dragged him off the beach to show him to Universal-International and they shrugged and sent him to Batomi Schneider to study—when all that happened, Bob thought maybe this acting bit might possibly bring him enough money so that he could get back into the ski equipment business. Like skiing, he found it wasn’t easy. It was a challenge, and by the time he’d mastered the challenge he was swallowed up in it, neck-deep in something he loved.

To a young man as persevering as all this and as handsome, as likable and as talented. all these things are sure to come. It shouldn’t be too many years before Robert Francis can take time in the morning to see if it’s raining before he kisses his wife goodbye and then stops off at his ski shop on the way ic the dressingroom that has a star on the door.

THE END

—BY JIM NEWTON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE APRIL 1955

No Comments